Corpse poison

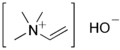

Ptomain (or Ptomaïn; from Gr. Πτώμα ptōma ' corpse ', with the suffix -in ; plural: Ptomaine) - corpse poison , corpse base , corpse alkaloid , cadaver alkaloid or, more rarely, septicin ( septicin ) - is a rather ancient name in German-speaking countries, among other things for the relatively non-toxic biogenic amines cadaverine and putrescine , which are produced by the putrefaction of proteins as a result of microbial decomposition of lysine and ornithine through decarboxylation , and which are one reason for the decayed smell of corpses. Only the neurin produced by the dehydration of choline has a certain acute toxicity . In addition, sulfur compounds such as hydrogen sulphide also play a role, which are toxic in themselves but are not present in high concentrations.

Origin and use of the terms

The various terms for "corpse poison", especially Ptomain, were coined in the German-speaking world towards the end of the 19th century, when Ptomain research reached its peak, and the term appeared in English literature with a delay. With the increase in knowledge through chemical and biochemical analysis, the technical terms for the identified substances were used more and more from the first third of the 20th century and the group name "Ptomain" (or "corpse poison") disappeared from the scientific literature because it was so seen no "substance called corpse poison".

Ptomain Research

W. Marquardt, pharmacist and medical assessor in Stettin , isolated the first ptomain from decaying body parts in 1865 and described it as a liquid similar to that of coniin . In 1866 Henry Bence Jones and August Dupré found an alkaloid-like substance in human and animal organs, tissues and fluids, which they called "animal chinoidin" (English animal chinoidin ; loosely translated as " quinine- like substance in animals") and in 1869 Zülzer isolated it and sunshine from putrefactive liquids (yeast, blood, meat, etc.) the first crystallizable ptomain that showed similarities with atropine and hyoscyamine .

Ludwig Brieger , who published a lot on ptomaines in humans and in other organisms, also counted muscarin , C 1 - to C 5 -amines, neuridin , "tetanotoxin" and "tetanin" (both not analyzed in detail) in addition to the substances mentioned above , " Mytilotoxin ”(presumably a form of saxitoxin ),“ Mydatoxin ”(from four month old horse meat and from human corpse parts),“ Gadinin ”(from rotten stockfish ) and“ Typhotoxin ”to the ptomaines.

Research into the ptomaine was especially important for the court chemistry of the time, since the body's own alkaloids, which were created after death through biochemical degradation processes - of whatever kind - could simulate the presence of supposed plant toxins.

Atropine

(mixture of the isomers ( R ) - and ( S ) - hyoscyamine )

Formation of other toxins

It was soon recognized that other substances were formed by the action of bacteria in the early stages of putrefaction, even before the typical rotten smell draws attention to them. Finally, as the putrefaction progresses, the dead organism is further metabolized (broken down) by fungi (formerly known as “saprophytic fungi”, i.e. putrefactive fungi).

In earlier times both cadaver sections and patient operations were performed on the same table in medical lecture halls (when the exact biochemical relationships were not yet known) , often to the detriment of the patients, who then died of infections rather than "corpse poison" (see Ignaz Semmelweis ). When dealing with corpses, such as in funeral homes, one knows that a harmful effect due to skin contact or inhalation of “corpse poison” is excluded. In the case of oral ingestion, injection or violent damage , diseases caused by bacterial toxins (e.g. the proteins botulin and tetanus toxin ) or microbial infections are very possible.

This led to biological warfare early on , in which corpses (human or animal corpses) were catapulted into besieged cities or used to poison wells . Depending on the cause of death and the degree of putrefaction , a certain pathogen - for example plague bacteria , the cholera toxin produced by Vibrio cholerae or the tetanus toxin from Clostridium tetani - is usually responsible for the pathogenic effect.

literature

- F. Gräbner: Contributions to the knowledge of the Ptomaine in judicial-chemical relation . (PDF) dissertation; Schnakenburg's Buchdruckerei, Dorpat 1882

- Conrad Willgerodt, H. Maas, Ludwig Brieger: Ueber Ptomaine (Cadaveralkaloïde) with reference to the plant poisons to be taken into account in forensic chemical investigations . C. Lehmann (1882)

- H. Oeffinger (Grand Ducal Baden District Doctor): The Ptomaine of the Cadaver Alkaloids . Wiesbaden 1885

- Ludwig Brieger: About Ptomaine - Further investigations about Ptomaine in 3 parts. Hirschwald publishing house, Berlin 1885–86

- Icilio Guareschi: Introduction to the study of alkaloids with special consideration of the vegetable alkaloids and the ptomaine . R. Gaertner's publishing house, Berlin 1896

- Meyers Konvers.-Lexikon . 5th edition. Bibliographer. Inst., Leipzig / Vienna 1896, pp. Volume 11, 176–177

Web links

- Christine Pernlochner-Kügler: Are corpses poisonous?

Individual evidence

- ↑ Wolfgang Legrum: Fragrances, between stench and fragrance . Vieweg + Teubner Verlag, 2011, ISBN 978-3-8348-1245-2 , p. 65.

- ^ "Ptomain" in German literature (1850–2000). NGRAM viewer

- ^ "Ptomain" in English literature (1850–2000). NGRAM viewer

- ^ Pharmaceutical Central Hall for Germany (1884), Volume 25, p. 285 .

- ↑ Schmidt's yearbooks of domestic and foreign complete medicine (1868), volume 139, p. 174

- ^ Medical record , Volume 33, 1888, p. 529.

- ↑ Archiv der Pharmazie , Volume 224, 1886, p. 481).