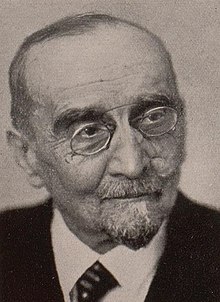

Rudolf Huch

Rudolf Huch (born February 28, 1862 in Porto Alegre ; † January 13, 1943 in Bad Harzburg ), pseudonym A. Schuster , was a German lawyer , essayist and author of primarily satirical novels and short stories, but also of educational and educational novels . His main theme here as there is the path of the German bourgeoisie from the provincial petty bourgeoisie to the bourgeoisie . He was the brother of the writer Ricarda Huch .

Life

Ricarda's older brother and cousin Friedrich Huchs grew up as the son of a wholesale merchant in Braunschweig . After studying law in Heidelberg and Göttingen , where he joined the Corps Brunsviga , Huch settled in Wolfenbüttel in 1888 as a lawyer and notary . From 1897 he lived and worked in Bad Harzburg , only interrupted by a stay in Helmstedt from 1915 to 1920.

plant

As a writer, Huch drew attention to himself mainly as a narrator in the succession of Goethe , Keller and Raabe . He himself, who recognized Wilhelm Raabe in particular as his role model, saw himself as a “romantic by blood”. His large, largely satirical and time-critical narrative, which also includes several autobiographical writings, found a wide audience in the first half of the 20th century .

Previously, the "painfully satirical" (reached Seidel ) Novel From the Tagbuch a cave pig (1896), in which he, the philistinism denounces what he had encountered in Braunschweig and Wolfenbüttel, and his essay on Nietzsche - cult , Ibsen and in naturalism that emerged in literature , which in the end More Goethe! (1899) comes, some notoriety. In the latter, Huch puts forward the thesis that " Zarathustra [...] influenced modern reading food, mainly prepared by women," far more than Götz von Berlichingen and The Sorrows of Young Werther . His call for more Goethe is also, as it were, for more “nature, health, reason, moderation and order” (Brauneck). In the early creative phase, Huch also wrote for the theater; mainly comedies. Tragedies like the early philanthropist (1895) and a fairy tale also appeared in print.

Among the thirty or so mainly satirical novels by the author, however, it is precisely the social studies The Two Knights Helmets (1908) and The Hellmann Family (1917), which literary criticism attaches the greatest importance to long after his death, which can be assigned to the development and educational novel . The novel about the Hellmann family was recognized by contemporary literary criticism as an “extraordinary representation of the development of the German bourgeoisie at the decisive turn of the world war” and was also a great success with the public - within a few years Die Familie Hellmann was reprinted over twenty times. The "humanly deeply moving" description, which the criticism of the Hellmann novel particularly emphasized, was one of the strengths of the brilliant narrator Huchs, whose humor, irony and fine observation skills were other attributes that criticism and readership alike valued in him. Because of this z. For example, the picaresque novel Wilhelm Brinkmeyer's Adventure, told by himself (1911), which can still exist today as a timeless piece of entertainment literature, is highly praised.

The story The great Halberstädter (1910), whose eponymous hero was the son of Duke Heinrich Julius von Braunschweig (1564–1613) who became known as "Toller Christian", his song of the Parzen (1920) and the Bad Honnef novel Spiel am Ufer (1927) are just a few more of Huch's many narrative successes.

In addition, Huch continued to work as a culture-critical essayist and, like his sister, published articles on literary studies . The aphorism was another form of expression of the writer, whose multiple cultural and social criticism, despite all the ridicule, always embodied a constructive approach shaped by humanism: "Sincerity, courage, love, spirit" were values that Huch described as true humanity. In addition to his writing activities, he was also the editor of a 1920 Reclam edition of the book Der Kampf ums Recht (1925) by Rudolf von Jhering .

During the time of National Socialism , the old Huch, whose books had previously been read with enthusiasm by the German-Jewish community, was exploited by the Nazis, to which he himself contributed as a member of the NSDAP. At the beginning of the thirties he approached National Socialism: In 1933 he was accepted into the “cleaned” and harmonized Prussian Academy of the Arts , Department of Poetry. In the same year, together with 87 other German writers, he signed the pledge to Hitler of the most loyal allegiance . In 1934 he published the anti-Semitic propaganda book Israel and We in the National Publishing House JG Huch. Huch remained a much-published and honored writer until the end of his life. In the year of his death, an edition of the works began “in agreement with the poet”, which, however, despite his very extensive literary work, did not exceed two volumes and was not continued after the end of the Second World War . His works Israel and We (1934), Dialogues (1935) and The Gray Fish (1937) were placed on the list of literature to be segregated in the Soviet occupation zone .

Today Huch is almost forgotten. A street in Bad Harzburg is named after him.

Fonts (selection)

Novels

- From the diary of a cave newt (1896)

- Comedians of Life (1906)

- The two knight helmets (1908)

- Wilhelm Brinkmeyer's Adventure (1911)

- Talion (1913)

- Junker Otto's trip to Rome (1914)

- The Hellmann family (1917)

- Hans the Dreamer (1918)

- The Song of the Parzen (1918)

- Game on the Shore (1927)

- Anno 1922 (Hanseatische Verlagsanstalt Hamburg 1929)

stories

- The great Halberstaedter (1917)

- The Chamberlain and His Sons (1917)

- Old man's summer (1925)

- The Lord Neveu and his moon goddess (1926)

- A Philanthropist (1936)

- Kilian and the Kobolds (1942)

Drama

- The Philanthropist (1895)

- The church building (1900)

- Goblins in the Farmhouse (1901)

- Disease (1903)

Autobiography

- What is it? (1898)

- From a Close Life (1924)

- My Way (1936)

Essays, studies, theoretical writings

- Berlinism in Literature, Music and Art (1894)

- More Goethe! (1899)

- A Crisis (1904)

- Pfeiffer & Schmidt; Chronicle e. Brunswick trading house from its origins in 1690 to the present day (1929)

- Israel and us. A dialogue between an old man and a middle-aged man. An educational pamphlet. (1934)

- Dialogues (1934)

- The Bismarck Tragedy (1938)

- William Shakespeare (1942)

- What is popular (in: Der Burglöwe; Braunschweiger Contributions to German poetry 1944)

literature

- Ernst Sander: Rudolf Huch. The poet and work. A study. 1922.

- Hellmuth Langenbucher : Rudolf Huch. In: The New Literature. 1934.

- Ricarda Huch: From my life. In: Westermann monthly books. 1937.

- Dorothea Glaser: Rudolf Huch, the citizen. 1941.

- Ewald Lüpke: Greetings to Rudolf Huch. For my 80th birthday. 1942.

- Kurt Matthies: Literary Encounters. About the baroque poem, Matthias u. Hermann Claudius, founder, Kleist, Dauthendey, Hofmiller, Rudolf Huch u. Hill. 1943.

- Christian Jenssen: Rudolf Huch. 1943.

- G. Grabenhorst, Lis. Huch, Ina Seidel: Farewell to Rudolf Huch. 1944.

- Eckhard Schulz: Huch, Rudolf. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 9, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1972, ISBN 3-428-00190-7 , pp. 708 f. ( Digitized version ).

Web links

- Literature by and about Rudolf Huch in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by Rudolf Huch in the Gutenberg-DE project

- Historical novel project, database: Rudolf Huch (with picture) at histrom.literature.at

Individual evidence

- ^ Nazi Propaganda Literature (PDF; 1.9 MB) in the Library of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research: Source Materials on Modern German Anti-Semitism, National Socialism and the Holocaust.

- ↑ Entry 1946 on polunbi.de

- ↑ Entry 1948 on polunbi.de

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Oops, Rudolf |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | A. Schuster |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German writer |

| DATE OF BIRTH | February 28, 1862 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Porto Alegre |

| DATE OF DEATH | January 13, 1943 |

| Place of death | Bad Harzburg |