Battle of the Volkhov

1941: Białystok-Minsk - Dubno-Lutsk-Rivne - Smolensk - Uman - Kiev - Odessa - Leningrad blockade - Vyazma-Bryansk - Kharkov - Rostov - Moscow - Tula

1942: Rzhev - Kharkiv - Company Blue - companies Braunschweig - company Edelweiss - Stalingrad - Operation Mars

1943: Voronezh-Kharkov - Operation Iskra - North Caucasus - Kharkov - Citadel Company - Oryol - Donets-Mius - Donbass - Belgorod-Kharkov - Smolensk - Dnepr

1944: Dnepr-Carpathians - Leningrad-Novgorod - Crimea - Vyborg-Petrozavodsk - Operation Bagration - Lviv-Sandomierz - Jassy-Kishinew - Belgrade - Petsamo-Kirkenes - Baltic States - Carpathians - Hungary

1945: Courland - Vistula-Oder - East Prussia - West Carpathians - Lower Silesia - East Pomerania - Lake Balaton - Upper Silesia - Vienna - Oder - Berlin - Prague

The Volkhov Battle (also Ljubaner Operation , Russian Любанская операция ) was an offensive by the Red Army in World War II from January 7 to April 30, 1942.

prehistory

After the encirclement of Leningrad ( Leningrad Blockade ) the advance of the German Army Group North in the battle for Tikhvin from October 16 to December 30, 1941 came to a standstill.

aims

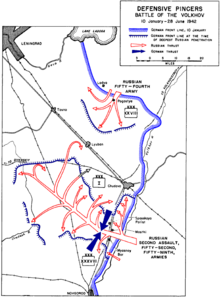

The troops of the Volkhov Front (4th, 52nd and 59th Armies and 2nd Shock Army ) under Kirill Merezkow and the 54th Army of the Leningrad Front had reached the Volkhov and the Mga - Kirishi railway line at the turn of the year 1941/42 and should now advance towards Ljuban against the divisions of the 18th Army of Army Group North . Their task was to enclose the German troops, which had taken up strong defensive positions at Kirishi and on the left bank of the river Volkhov, and thus initiate the demolition of the Leningrad blockade .

course

On January 7, 1942, the Soviet offensive began in a difficult - because partly wooded - snow-covered area. The attacks were directed against the German 126th and 215th Infantry Divisions . It was not until January 17 that the first line of defense of the German XXXVIII. Break through Army Corps . The northern flank of the main attack group comprising the 2nd Shock Army took was from the 4th and 59th Army (Major General Galanin , from April General IT Korownikow covered) section Wolchow which their troops on both sides of Tschudowo concentrated. By the end of January, the troops of the 2nd Shock Army under General Nikolai Klykov had advanced almost 75 kilometers and reached the entrances to the city of Lyuban with the Novgorod - Leningrad railway .

The 54th Army (General Ivan Fedjuninski ) of the Leningrad Front succeeded only at the end of March, the lines of the German XXVIII. Army corps to break through at Pogostje west of Kirishi and advance about 22 kilometers deep over the Tigoda section into the area northeast of Ljuban. About 20 kilometers were missing from the planned connection with the 2nd Shock Army, which was thwarted by counter attacks by the German 1st Army Corps .

In the meantime the German 18th Army had concentrated eleven divisions and one brigade opposite the Soviet Volkhov Front and on March 15 began a counter-offensive. On March 19, the 2nd shock army was cut off. On March 27, the 52nd and 59th Armies succeeded in breaking open the encirclement again with heavy losses; however, the access to the positions of the 2nd Shock Army was only three to five kilometers wide.

Despite this difficult situation, the Stawka continued to insist on a continuation of the offensive, which in fact had already come to a standstill. It was not until April 30, 1942, that the 2nd Shock Army, now under the command of General Andrei Vlasov , was given the order to move to the defensive positions it had reached, thus completing the Lyuban offensive operation. General Vlasov did not receive permission from the Stawka to withdraw that had become necessary until the end of May.

The opened connections to the 2nd Shock Army were again severed by the Germans. Between June 22nd and 27th, 1942 General of the Kleffel Cavalry took over the task of building the boiler from the north together with XXXVIII. Army Corps (General of the Infantry Haenicke ) to narrow down and to smash the forces there. In the last Soviet attempts to break out of the pocket on June 24th and 25th, the army was almost completely wiped out. Only between 6,000 and 16,000 Red Army soldiers were able to reach their own lines, 14,000 to 20,000 were killed in this escape attempt alone.

consequences

The Red Army had gained ground, but with disproportionately high losses (95,000 dead and prisoners, 213,000 wounded). The objectives of the operation were not achieved; the 2nd shock army was completely wiped out. General Vlasov initially hid behind the German lines, but was taken prisoner on July 12, changed sides and subsequently became the commander of the Russian Liberation Army, allied with Germany .

In order to get an impression of the severity of the fighting, the statistical figures of the German 215th Infantry Division can be used as an example. It suffered the following losses in the period from November 23, 1941 to July 18, 1942:

- 961 dead

- 3119 wounded

- 180 missing people

- 1633 Frost diseases II. And III. Degree

During the period mentioned, the light field howitzers of the division alone fired 140,000 grenades and the heavy field howitzers of the division 30,000 grenades.

The Leningrad blockade continued. The Soviet troops tried again in August 1942 in the First Battle of Ladoga to blow up the siege and thus beat the German company Nordlicht .

literature

When looking at Soviet sources, with the exception of samizdat and tamizdat literature that was published up to 1987, the activities of the Soviet censorship authorities ( Glawlit , military censorship) in revising various contents in line with Soviet ideology must be taken into account. (→ censorship in the Soviet Union )

- Nikolai Nikolajewitsch Nikulin: ВОСПОМИНАНИЯ О ВОЙНЕ. (German: memories of the war); Verlag Staatliche Ermitage Sankt Petersburg 2008. ( online )

- Ye. Klimchuk: The 2nd Strike Army and General Vlasov - Or Why Because of One Traitor the Blame Was Laid on the Whole Army. Sovietsky Voin magazine . Issue 4 1990. (English)

- David M. Glantz: Soviet Military Deception in the Second World War. Frank Cass Verlag, New York 1989, ISBN 0-7146-3347-X , pp. 68-71.

- M. Chosin: Об одной малоисследованной операции. (German: About a poorly evaluated military operation), magazine Военно-исторический журнал. Issue 2, 1966. ( online )

- Kirill Merezkow: На волховских рубежах. (German: On the banks of the Volkhov), magazine Военно-исторический журнал. Issue 1, 1965.

Web links

- Ljubaner Operation (Russian)

- Brief description of the Ljuban operation, website on the course of the Leningrad blockade (Russian)

- Soviet casualties as a result of the Ljuban operation (Russian)