Battle of Fort Eben-Emael

| date | 10. bis 11. May 1940 |

|---|---|

| place | Fort Eben-Emael in Belgium |

| output | Tactical victory of the German troops |

| consequences | Burglary of the fortress ring of Liège and occupation of the bridges over the Meuse and the Albert Canal |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

| Commander | |

|

Jean Jottrand ( Major ) |

|

| Troop strength | |

| over 1000 soldiers (estimated) | 493 soldiers |

| losses | |

|

60 dead, |

43 dead |

Battle of the Netherlands

Maastricht - Mill - The Hague - Rotterdam - Zeeland - Grebbeberg - Afsluitdijk - bombing of Rotterdam

Invasion of Luxembourg

cobblestone line

Battle of Belgium

Fort Eben-Emael - KW line - Dyle plan - Hannut - Gembloux - Lys

Battle of France

Royal Marine - Ardennes - Sedan - Maginot Line - Weygand Plan - Arras - Boulogne - Calais - Dunkirk ( Dynamo - Wormhout ) - Abbeville - Lille - Paula - Fall Rot - Aisne - Alps - Cycle - Saumur - Lagarde - Aerial - Fall Braun

The airborne operation against the Belgian Fort Eben-Emael was a battle between the Belgian and German armed forces at the beginning of the so-called western campaign in World War II .

overview

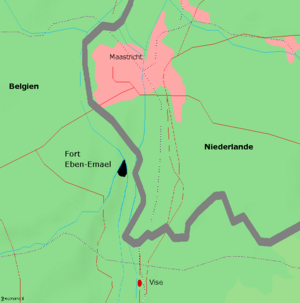

The battle to take the Sperrfort took place on May 10 and 11, 1940. The capture was an important part of the western campaign, the German invasion of the Benelux countries and France , which was designated in the planning as a crucial part of the offensive. An attack group of German parachute pioneers was commissioned to capture Fort Eben-Emael , a Belgian fortress in the Liège fortress ring, whose artillery guns dominated several important bridges over the Albert Canal . These bridges should be conquered as undamaged as possible in order to guarantee the army forces the further advance into Belgium and France without delay.

Part of the German airborne troops attacked the fortress directly in order to eliminate the garrison and its artillery. At the same time, other paratrooper combat groups took action against the three bridges that led across the Albert Canal. The fortress was captured and, like the bridges at Vroenhoven and Veldwezelt , which had also been conquered, were defended against Belgian counterattacks until the heads of the German 18th Army arrived from Aachen . The Kanne Bridge was blown up by the defenders.

The battle was a decisive victory for the German troops. The airborne troops suffered losses, but they managed to hold the bridges until the arrival of the German forces. The possession of the fort and the remaining bridges contributed significantly to the success of the western campaign.

history

German war planning

In October 1939 the commander of the parachute troops, Kurt Student , was tasked with task forces to ensure the rapid capture of the bridges and the fortress.

To carry out the order, the Koch Sturmabteilung with a total strength of 353 men and 41 cargo sailors, divided into 4 storm groups "Granit" (fortress Eben-Emael), "Beton" (Vroenhoven bridge), "Stahl" (Veldwezelt bridge) and "Eisen “(Bridge Canne) split. Each group, each with 1 lieutenant, 2 sergeants, 22 non-commissioned officers and 57 men, was divided into eleven storm troops of seven to eight parachute pioneers each. The parachute pioneers were armed with submachine guns, carbines, pistols, hand grenades, flamethrowers and explosives.

Since an exact landing with parachutes was not possible and pioneering technical means, especially shaped charges, were also carried, another possibility had to be found. Kurt Students planning staff found a solution: There are glider type DFS 230 used by towing aircraft Junkers Ju 52 / 3m were dragged over German territory to great heights and unlatched there, and then 30 km from the German border to the bridges over to cover the Albert Canal and Fort Eben-Emael in gliding flight - almost noiselessly.

Eben Emael fortress

The German planning staff had gained a lot of information about the fortress through reconnaissance flights (photos were probably taken of civil aircraft flying the Cologne - Paris route, which has been in service since 1926). An attack by conventional means seemed impossible. The aerial reconnaissance photos showed that there was virtually no anti-aircraft defense on the fort and that the fort's crew occasionally played football on the plateau. From this it was rightly concluded that it was not mined. The German plan of attack was based on these findings.

Platoon leader of the Granit group was Lieutenant Rudolf Witzig . The groups started with 10 to 11 gliders each in Cologne-Ostheim (Ostheim Air Base) and Cologne-Butzweilerhof . The tow rope from which Witzig's glider was hanging broke when the groups met over Efferen near Cologne. The glider pilot tried to turn back to Ostheim, but only made it to a meadow on the other side of the Rhine. Another glider had to land prematurely due to a misunderstanding at Düren. Witzig organized a new towing machine for the cargo ship that landed in Cologne and was able to land on the roof of the fort around 8:30 a.m.

The remaining cargo gliders of the Granit storm group landed in steep spirals on the almost half a square kilometer roof of the fort at dawn on May 10, 1940. The few soldiers of the Belgian crew who spotted one of the gliders believed that Allied planes were in need , as the German gliders came from the Belgian side after flying around the fort. At the same time the general German attack on the Netherlands, France and Luxembourg began at dawn .

When the fort was stormed, shaped charges were used for the first time as a weapon against the armored parts of the fortress. The heaviest of these shaped charges weighed 50 kg. The shaped charge had to be placed directly on armor. Around 45 seconds after the timer was activated, they ignited. The then developing metal spike penetrated any armor at a speed of 15,000 m / s.

The bridge at Canne, the one at Vroenhoven and the one at Veldwezelt were also approached with gliders. After releasing, the tow planes flew another 40 km into the Belgian hinterland, where they dropped 200 paratroopers at a height of 400 m as a distraction to tie up Belgian reserves.

Fighting

The fort was alerted, but not yet fully ready for action: Plant 13 was not yet manned, Plant 31 had no ammunition and the 7.5 cm cannons of Plant 12 were still greased; Plant 24 could not be made ready for action because the ammunition elevator did not work and parts of the fuse setting machine were also missing. The commandant, Major Jottrand, had a crew of around 1,200 soldiers.

At around 5:25 am, half an hour before sunrise (the pilots could see their landing sites sufficiently), nine cargo gliders and 82 parachute pioneers from the "Granit" storm group landed on the roof of the fortress.

Seven gliders landed in close proximity to their combat targets; two at the northern tip of the fortress, from where they were initially unable to intervene in the battle. On landing, they were shot at by four machine guns, but two of them soon failed due to jamming, while the third machine gun was knocked down by the first sailor to land and the fourth was eliminated by the crew who disembarked.

Within ten minutes of landing, the seven storm troops - each with a shaped charge attached - blew up all the fort's artillery works (except for plant 9), as well as the FlaMG (plant 29), infantry unit 30 and a ventilation shaft (plant 10). Works 12 and 18 were blown up to the bottom. The attackers clouded some observation domes. The fort was now "blind"; the defenders could not get an overview of the situation.

A bent fan blade made so much noise that the defenders believed the attackers were going to undermine the hill to blow it up. The enormous detonations of the shaped charges that shook the whole hill also contributed to these fears. The force and noise of the detonations and the use of smoke grenades so unsettled the defenders that they retreated into the deeper tunnels of the fortress.

Later the German attackers tried several times to blow up a way into the interior of the fort; In some cases, however, this only succeeded in advancing storm pioneers with demolition troops.

The Germans managed to penetrate the fort by blasting a hole in the “Maastricht 1” casemate . The Belgian crew of the casemate were killed by the explosion; The fort's crew then blocked access to the casemate with steel profiles and sandbags. Behind this 50 to 80 centimeter thick obstacle, the Belgian soldiers took position and waited for the enemy to break through the barricaded doors.

This turned out to be a tactical mistake, as it gave the Germans enough time to attach a 50 kg shaped charge to the doors and detonate it with a time fuse.

The explosive pressure of the shaped charge destroyed the barricade and killed the Belgian soldiers holed up behind the doors. In the corridor there were barrels or boxes with chlorinated lime to disinfect the toilets, which burst due to the pressure of the explosion and released fumes. These were distributed in the corridors, so that the Belgians assumed that the Germans were using poison gas .

In addition, the pressure of the explosion destroyed the 20-meter-high steel structure of the turret stairs, so that the Germans could no longer use the tower as an entrance. After this experience, the Germans refrained from conquering other towers in this way, as the fort should continue to be used after the conquest.

Since the fortress commander realized at this point that only regaining the plateau could prevent the fort from being lost, he ordered the outage . In order to take the plateau again, the fort crew would have had to advance there from below, because there was no access to the plateau from above. The defenders were numerically 10: 1 superior; but they did not use enough strength to drive the German soldiers from the roof of the fort. In addition, the Germans had a good defensive position there and were able to hold their positions. The Belgian leadership in Liège could not bring itself to a decisive counterattack either.

The commanding officer and crew could not see which forces were attacking the fort. The crew kept on the lookout for enemy bombers because an attack with aerial bombs was expected. There was also considerable psychological pressure; they feared because of the tremors that the plant would collapse. At that time, shaped charges and their effects were largely unknown. So it remained a mystery to the crew how their guns could be switched off so quickly.

The next morning, relief troops of the Army, Infantry Regiment 151, reached Fort Eben-Emael by land. Sergeant Portsteffen from Pioneer Battalion 51 was the first to fight his way to the paratroopers in a rubber dinghy under enemy fire over the Albert Canal at around 7:00 a.m. For a few hours there was tough fighting over the entrance plant and the canal.

The fort commander, Major Jottrand, asked the Belgian General Staff to decide whether to give up or not. The Belgian leadership left this decision to the major. He capitulated at 11:30 a.m. on May 11th.

24 Belgian and six German soldiers were killed in the fighting. All other Belgian soldiers were taken prisoners of war. These were kept strictly separated from other prisoners of war in order to prevent information about the use of the gliders and shaped charges from leaking out.

Wording of the Wehrmacht report :

Saturday, May 11, 1940: ( special report ) The strongest fort of Liège Fortress, Eben-Emael, which dominates the crossings over the Meuse and the Albert Canal near and west of Maastricht, surrendered on Saturday afternoon. The commandant and 1,000 men were taken prisoner.

As early as May 10th, the fort was incapacitated by a selected division of the Air Force under the leadership of Lieutenant Witzig and using new means of attack and the crew was held down. When an army unit attacking from the north succeeded in establishing contact with the Witzig division after a hard fight, the crew dropped their weapons.

Sunday, May 12, 1940 The crossing over the Albert Canal between Hasselt and Maastricht is forced. Fort Eben-Emael, south of Maastricht, the strongest cornerstone of Liège, is, as already announced in a special report, in German hands. The commander and the crew of 1000 men have surrendered.

Further consequences for the war

From a psychological point of view, the rapid fall of Eben-Emael was fatal for the Allies, because they knew, within the French military doctrine derived from the First World War, about the aggressor's methods with regard to offensive tank units and hollow weapons against defensive fortifications. The military benefit of the Maginot Line , which was built at great expense by France, and the Swiss defensive bunker systems were thus called into question.

During the war, the facility was often shown to selected visitors from countries that were allied with the German Reich; but the Germans carefully kept their methods of attack secret.

At a meeting in Hendaye on October 23, 1940, Hitler tried to persuade the Spanish dictator Franco to join the war on Germany's side. Franco should occupy the British Gibraltar in a surprise coup. For this purpose, Hitler offered Franco the soldiers who were successful at Eben-Emael. Franco refused; Spain remained neutral throughout World War II .

Eben-Emael today

Eben-Emael has been a museum since 1999, which can be visited once a month on Sundays. There are also guided tours in German.

The outdoor facilities are freely accessible. The traces of the at times very fierce battle for the fort are still unmistakable; so all the destroyed cannons and armor parts are still there.

Very close to the main entrance of the fort is the entrance to the tunnel leading to the Albert Canal. It had nothing to do with the fort, but only served as an underground entry and exit for trucks when the canal was enlarged. This meant that cumbersome serpentine journeys could be avoided.

photos

literature

- Dieter Heckmann, Günter Schalich: Attack from the air - Fort Eben-Emael and the bridges on the Albert Canal. In: Hans-Josef Hansen: Felsennest - The forgotten leader's headquarters in the Eifel. Construction, use, destruction. Aachen 2008.

- Cajus Bekker: The Luftwaffe War Diaries - The German Air Force in World War II . Da Capo Press, Inc., 1994, ISBN 0-306-80604-5 .

- Gerard M. Devlin: Paratrooper - The Saga Of Parachute And Glider Combat Troops During World War II . Robson Books, 1979, ISBN 0-312-59652-9 .

- Simon Dunstan: Fort Eben Emael. The key to Hitler's victory in the West . Osprey Publishing, 2005, ISBN 1-84176-821-9 .

- Peter Harclerode: Wings of War: Airborne Warfare 1918-1945 . Wiedenfield and Nicholson, 2005, ISBN 0-304-36730-3 .

- ER Hooton: Air Force at War; Blitzkrieg in the West . Chevron / Ian Allen, 2007, ISBN 1-85780-272-1 .

- Volkmar Kuhn: German Paratroops in World War II . Ian Allen, Ltd., 1978, ISBN 0-7110-0759-4 .

- Franz Kurowski: Knights of the Wehrmacht Knight's Cross Holders of the Paratroopers . Schiffer Military, 1995, ISBN 0-88740-749-8 .

- James Lucas: Storming Eagles: German Airborne Forces in World War Two . Arms and Armor Press, 1988, ISBN 0-8536-8879-6 .

- Maurice Tugwell: Airborne To Battle - A History Of Airborne Warfare 1918–1971 . William Kimber & Co. Ltd., 1971, ISBN 0-7183-0262-1 .

- René Viegen: Fort Eben-Emael , 1st edition. Edition, Fort Eben Emael, Association pour l'étude, la conservation et la protection du fort d'Eben-Emael et de son site ASBLn ° 8063/87, 1988.

- The Wehrmacht Reports 1939–1945 Volume 1, September 1, 1939 to December 31, 1941 . Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag GmbH & Co. KG, Munich 1985, ISBN 3-423-05944-3 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f Florian Stark: Eben-Emael 1940: 82 paratroopers against the largest fort in the world . In: THE WORLD . May 13, 2015 ( welt.de [accessed February 5, 2020]).

- ↑ www.koelner-luftfahrt.de

- ↑ Cajus Becker, attack height 4000, Hexne book 975, Wilhelm Heyne Verlag Munich, 1972 p.136ff

- ↑ Werner Pissin: The capture of the fortress Eben-Emael on 10./11. May 1940 . In: General Swiss Military Magazine (ASMZ) . tape 125 , no. 8 , 1959, pp. 588 , doi : 10.5169 / seals-37841 .

- ↑ Milan Blum, Martin Rábon, Uwe Szerátor: The attack. Volume 1, p. 124.

- ↑ Milan Blum, Martin Rábon, Uwe Szerátor: The attack. Volume 1, p. 92.

- ^ W. Nicolai: The Wehrmacht Reports 1939–1945. Volume 1, p. 144 f.

- ^ W. Nicolai: The Wehrmacht Reports 1939–1945. Volume 1, p. 145.

- ↑ More details in the article Francisco Franco # Role in World War II