Battle of Philippi

| date | 42 BC Chr. |

|---|---|

| place | Philippi |

| Casus Belli | Assassination of Caesar |

| output | Victory of the Caesarians |

| consequences | Division of the empire |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

| Commander | |

|

Mark Antony and Octavian |

|

| Troop strength | |

| approx. 100,000 foot troops and 13,000 horsemen | 80,000 foot troops and 20,000 horsemen |

In the double battle at Philippi, west of the city of Philippi in Macedonia, they were victorious in October / November 42 BC. BC the Roman triumvirs Mark Antony and Octavian (later Emperor Augustus ) in two meetings over the supporters of the republic, Mark Junius Brutus and Gaius Cassius Longinus , who were also among the leaders of the assassination attempt on Gaius Julius Caesar .

prehistory

After Caesar's assassination (March 15, 44 BC), the consul Antonius initially succeeded in usurping the greatest power in Italy. The leading Caesar killers Brutus and Cassius left Italy, gained control over large parts of the east of the Roman Empire and also forced the neighboring client princes to provide them with support in the form of money and auxiliary troops . They quickly raised the largest possible army, benefiting from the fact that the eastern provinces were much richer than the western ones. After initially serious differences between Antony and the heir of Caesar Octavian, the two came to an agreement at the end of October 43 BC. BC with Marcus Aemilius Lepidus , through the Second Triumvirate to conclude an alliance to fight the murderers of Caesar. In the west of the Roman Empire, which they ruled, they eliminated their political opponents with great severity ( proscriptions ), especially representatives of the party loyal to the republic, and prepared the attack on the Caesar murderers in the east. Sextus Pompeius , who u. a. Sicily controlled but remained a threat in the west.

For the triumvirs, crossing the Adriatic with their expeditionary army was difficult, as they had significantly fewer naval forces than their opponents. Cleopatra wanted to bring them an auxiliary fleet, but got caught in a storm and was forced to turn back. After the triumvirs had already been able to transfer their first troop contingents to the east by sea, Antonius was blocked for a long time in the port of Brundisium by the ships of Lucius Staius Murcus and called Octavian for help. In front of the common fleet of the triumvirs, Staius Murcus had to retreat so that Antonius and Octavian could land safely with their main army in Dyrrhachium . After that, Staius Murcus was supported by 50 ships from Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus . Together, both admirals were able to almost completely prevent the supply of the triumvirs from Italy.

Brutus and Cassius marched with their army from western Asia Minor across the Hellespont to the west. An advance party of 8 legions of Antonius under Lucius Decidius Saxa and Gaius Norbanus Flaccus had already advanced from the east to the passes on the north coast of the Aegean Sea , but withdrew to Amphipolis after being bypassed by the approaching enemy army . The murderers of Caesar, for their part, went to Philippi.

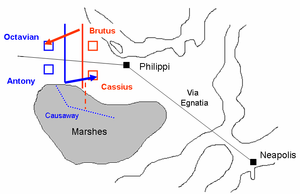

Lineup

The Caesar murderers built a heavily fortified double camp on both sides of the Via Egnatia in the plain west of Philippi, which was protected in the south by a large swamp and in the north by inaccessible mountains. To the south of the swamp rose an impassable mountainous area that reached as far as the seashore. The northern camp was the base of Brutus, while the southern one was under Cassius. The drinking water supply was ensured by a few nearby streams. Wood used as construction and fuel could be felled in the dense forest of the mountain region north of Philippi. The supply lines via the port of Neapolis , the naval base of Brutus and Cassius, and the opposite island of Thasos were also secured. The Caesar killers' locking bolt blocked the way to the east, and to the west of their double camp the terrain sank, another obstacle for an enemy attacking from the west.

After the arrival of the triumvirs in Dyrrhachium, Octavian initially stayed behind due to illness, while Antony moved with his army to Philippi and set up his base west of the camp of the Caesar murderers. Some time later, Octavian, who had not yet fully recovered and was transported in a sedan chair, came to see Antonius. Both generals and their troops moved into a common camp. The Caesar murderers were in no hurry, as their supplies were secured on site and by sea. Their tactics consisted of waiting in their well-situated, strong defensive position for the attack of their opponents, who soon had to take the initiative due to the advanced season and their great supply problems. The triumvirs found little wood and water in the place of their camp and could only get a small supply from the areas they now controlled in the west, such as Macedonia, while the overseas supply was almost entirely absent due to the blockade by the Caesar murderers' fleet.

There were considerable troop contingents on both sides: the Triumvirs had 21 to 22 legions, 19 of which they used in the first battle at Philippi; the Caesar murderers came to 17 legions. Accordingly, the triumvirs commanded about 100,000 legionnaires and an additional 13,000 horsemen, the republicans about 80,000 legionnaires and 20,000 horsemen. The cavalrymen were provided by the respective allies, who also provided the warring parties with a considerable number of additional infantrymen. However, the triumviral legions were much more battle-tested than those of their opponents.

First battle

On the side of the triumvirs Antonius de facto took over the supreme command and was forced to take the offensive due to growing supply problems and increasing autumnal cold. Because of little chance of success, he did not attempt a frontal attack on the strongly fortified enemy base, but secretly built a dam through the moor south of Cassius' camp in order to threaten the supply routes of the Caesar murderers and to be able to attack from the south. Cassius only became aware of Antonius' tactics late and tried to block the way over the dam by building cross entrenchments. In the ensuing first battle at Philippi, which presumably took place on October 23rd (the literature also mentions October 3rd), Antonius gradually let his troops advance over the dam and was able to conquer Cassius' camp with considerable losses. At the same time Brutus made a counterattack, overran Octavian's troops and penetrated the camp of the triumvirs, in which the sick Octavian was fortunately not found. Cassius was apparently completely uninformed about the course of the fight on the wing commanded by Brutus and, after conquering his camp, mistakenly believed in total defeat; therefore he ordered his freedman Pindarus to kill him. This was a painful loss for Brutus. Allegedly he referred to Cassius as the "last Roman".

Octavian owed his life to the favorable circumstance that he was not in the camp when the Brutus attacked, but traced him back in his memoirs to the warning by a dream of his doctor Marcus Artorius Asklepiades . It disappeared for a long time after the battle. Some fighters showed Brutus their bloody swords with the declaration that they had killed Octavian. Allegedly, the young Caesar heir hid in the swamp for three days. In any case, he hadn't distinguished himself particularly well during the fight.

The triumvirs recorded a casualty loss twice that of their opponents. On the day of the first battle at Philippi, the fleet of the Caesar murderers almost completely destroyed a squadron of Gnaeus Domitius Calvinus , which the triumvirs a. a. should have brought two legions of reinforcements. All in all, the Caesarians had suffered a clear tactical defeat in their first exchange of blows. However, it should show that the death of Cassius was decisive for the war, since he was the military head of the Caesar murderers.

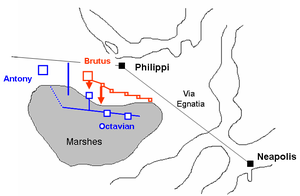

Second battle

Brutus had the body of Cassius secretly buried on Thasos, because he feared that a burial in the presence of his soldiers would lead to their demotivation. He consistently avoided any further field battle, although he was now threatened by his opponents not only in the west, but also in the south. He still had a strong fortified position and secured his supply lines, while the supply possibilities of the triumvirs had to deteriorate further and further as winter approached. To keep his soldiers in line, Brutus gave them rewards. Antony finally had to send a legion of soldiers to Greece to get food. But the officers of Brutus disagreed with their general's defensive tactics against a weakened and thus supposedly easily defeatable enemy, and his Caesarian veterans threatened to change sides. Allies also left Brutus. Amyntas , for example , the general of King Deiotaros of Galatia, joined the triumvirs, and a Thracian prince named Rhaskuporis I went home. Brutus was unable to defend his ideas as resolutely as Cassius and therefore rallied for battle about three weeks after the first battle.

This second battle, which presumably took place on November 16 (October 23 is also mentioned in specialist literature), did not begin until 3 p.m. This time Octavian held up better and was able to throw the opposing troops back to their camp with his legionnaires. His soldiers occupied the entrance to the camp of Brutus so that his retreating forces could not get in and fled past it in disorder. Antonius now attacked everywhere and sent his cavalry on all sides to intercept as many fugitives as possible. Brutus fled up a mountain with a significant army of four legions. His confidante Lucilius covered up the escape by pretending to be Brutus to the pursuers and wishing to be brought before Antonius. At this news Antonius hesitated for a while and then let the supposed Brutus come. Lucilius said boldly that he had deceived the soldiers and that Brutus was not captured. Antony was magnanimous and later even took Lucilius into his own service. Brutus himself asked a friend to kill him the day after the lost battle because his officers refused to attempt to recapture their camp. Shortly before his suicide, he is said to have complained in two quarters to an unknown tragedian that he revered virtue as reality, but that it had turned out to be a mere concept subject to chance. ("Virtue, you were just a name. I cultivated you as if you were reality, but you were only a slave to fate.")

consequences

Through their success at Philippi, the triumvirs decided the question of power largely in their favor, because with the death of Brutus his army disbanded; only Sextus Pompeius and the fleet of Caesar murderers operating in the Ionian Sea, to which many survivors of the losing side fled, remained a danger. Antonius accepted the surrender of 14,000 legionnaires and the fleet anchored near Thasos and generally treated the underdogs much more gently than Octavian. However, Quintus Hortensius , the son of the eminent orator Quintus Hortensius Hortalus , was executed on the orders of Antonius at the grave of his younger brother Gaius , because he in turn had been removed by Hortensius, as Brutus had requested.

Octavian is said to have dealt cruelly with the prisoners of war. So he let a father and his son, who asked for their lives, draw a lottery ticket for which of the two should be pardoned, and then watched as his son also committed suicide after his father was killed. He had Brutus' body beheaded in order to have its head laid at the Caesar statue in Rome, but the ship intended for the transport went down. Antony, on the other hand, gave the mutilated body of Brutus a cremation; he sent the ashes to Servilia , the mother of Brutus. The sparing of most of his defeated opponents brought Antonius sympathy, Octavian his ruthless actions but insults from prominent imprisoned representatives of the defeated party.

Numerous distinguished supporters of the republic fell in the battles at Philippi or were killed either by suicide or execution after the defeat, for example Marcus Porcius Cato , the son of the staunch Republican Marcus Porcius Cato Uticensis , Marcus Favonius , who had also quarreled with the Caesar murderers, Pacuvius Antistius Labeo , the father of the eminent legal scholar Marcus Antistius Labeo , also Marcus Livius Drusus Claudianus , the father of Octavian's later wife and first Roman Empress Livia , and Sextus Quinctilius Varus , the father of the great loser of the Varus Battle . Other followers of Brutus and Cassius, who are no longer mentioned in the sources after their death, may also have perished at that time, such as Lucius Tillius Cimber and Publius Servilius Casca . On the other hand, Marcus Valerius Messalla Corvinus and Lucius Calpurnius Bibulus survived , who were pardoned by Antonius. Also among the survivors was the poet Horace , who had fought as a tribune on the side of the Caesar murderers and who returned to Italy some time after the deaths of Brutus and Cassius. Overall, the double battle at Philippi cost the Roman people a high bloodletting. Around 40,000 soldiers were killed in the armed conflict and many more were wounded.

The Battle of Philippi was not an abrupt turning point, not a sudden end to the Roman Republic . The collapse of the republican order had already started with the murder of the tribune Tiberius Sempronius Gracchus in 133 BC. The leading riots began and continued through the civil wars of the next few decades. In the process, numerous members of the noble families had repeatedly found their deaths, so that the old senate aristocracy that governed the republic gradually disappeared. Individuals had more and more power over the Senate. The battle of Philippi therefore represents a certain end to this process of disintegration. At that time, however, the transition to a monarchical form of government was not yet complete, as there were still several independent rulers. Over time, Octavian was able to prevail against all remaining competitors. 36 BC BC he defeated Sextus Pompeius and in the same year disempowered Lepidus. 31 BC In BC he achieved the decisive victory in the battle of Actium against Antony and Cleopatra, who committed suicide the next year. This paved the way for Octavian's sole rule as Emperor Augustus.

swell

The main source on the Battle of Philippi is the fourth book of the Civil Wars by the war historian Appian . In addition, the portrayal of Cassius Dio in the 47th book of his Roman history and the Brutus Vita of the biographer Plutarch are important.

literature

- Jochen Bleicken : Augustus. A biography . Special edition. Fest, Berlin 2000, ISBN 3-8286-0136-7 , p. 159ff., Sketch map on p. 163. (The special edition corresponds to the first edition 1998, ISBN 3-8286-0027-1 .)

- Matthias Gelzer : Iunius 53. In: Paulys Realencyclopadie der classischen Antiquity Science (RE). Volume X, 1, Stuttgart 1918, Sp. 1013-1018.

- Pat Southern : Marcus Antonius , German 2000, pp. 94-103.

Web links

Youtube: Arte: The Fate of Rome - Channel: La Villa Stuttgart-Wangen

Remarks

- ^ Appian , Civil Wars 4, 82.

- ↑ Appian, Civil Wars 4, 82 and 4, 86; Cassius Dio 47, 35, 2; 47, 36, 4 - 37, 1.

- ^ Appian, civil wars 4, 86 and ö.

- ↑ Appian, Civil Wars 4, 87 and 4, 102-104; Cassius Dio 47, 35, 2-5; Plutarch , Brutus 38.

- ↑ Appian, Civil Wars 4, 105ff .; Cassius Dio 47, 35, 5 - 36, 1.

- ^ Appian, Civil Wars 4, 107f .; Cassius Dio 47, 37, 2 - 38, 4.

- ^ Troop numbers according to Jochen Bleicken, Augustus , 1998, pp. 160 and 162.

- ^ Appian, Civil Wars 4, 109–113; Plutarch, Brutus 41-43; Cassius Dio 47, 45, 2 - 46, 5.

- ↑ Plutarch, Brutus 44, 2; Appian, Civil Wars 4, 114.

- ↑ Plutarch, Brutus 41, 7ff .; Suetonius , Augustus 91, 1; Cassius Dio 47, 41, 3; Appian, Civil Wars 4, 110.

- ↑ Plutarch, Brutus 41, 7f. and 42, 3.

- ↑ Pliny , Naturalis historia 7, 148.

- ^ Appian, Civil Wars 4, 112.

- ^ Appian, Civil War 4, 115f .; Plutarch, Brutus 47; Cassius Dio 47, 47, 4.

- ^ Appian, Civil Wars 4, 114; Plutarch, Brutus 44, 2; Cassius Dio 47, 47, 2.

- ^ Appian, Civil Wars 4, 118; Plutarch, Brutus 44, 3; Cassius Dio 47, 47, 2.

- ^ Appian, Civil Wars 4, 122.

- ^ Appian, Civil Wars 4, 123f.

- ↑ Cassius Dio 47, 48, 2.

- ^ Appian, Civil Wars 4, 128f .; Plutarch, Brutus 49f .; Cassius Dio 47, 48, 4f.

- ^ Appian, Civil Wars 4, 130f .; Plutarch, Brutus 51f .; Cassius Dio 47, 49, 1f.

- ^ Suetonius, Augustus 13, 1f .; Cassius Dio 47, 49, 2.

- ^ Appian, Civil Wars 4, 135; Plutarch, Brutus 53 and Antonius 22; Cassius Dio 47, 49, 2; Valerius Maximus 5, 1, 11.

- ^ Suetonius, Augustus 13, 2.

- ↑ Jochen Bleicken, Augustus , 1998, pp. 165ff.

- ↑ Jochen Bleicken, Augustus , 1998, p. 167f.