The Epic of Gilgamesh

The Epic of Gilgamesh is a three-part oratorio for soloists, mixed choir and orchestra by the Czech composer Bohuslav Martinů (1890–1959), whose late work it is (1954/55, H 351).

Martinů wrote the English text of his work himself. The premiere took place in German ( The Gilgamesh Epos , text version by Arnold Heinz Eichmann). There is also a version in Czech ( Epos o Gilgamešovi , written by Ferdinand Pujman based on the Czech translation of Gilgamesh by Lubor Matouš ). In his text, Martinů puts philosophical questions in the foreground. Neither the exploits of Gilgamesh and Enkidu nor the description of the Flood were taken from the text.

In terms of composition, the work is worked out with great contrasts between the individual parts: there are both intoxicating scenes in a large cast as well as distinctive dialogues. As a component of the motif, the small seconds interval plays a decisive role throughout the entire work. It stands first for the people's fear of the ruler and later for the trepidation and mortal fear of this ruler himself. Choir and soloists take on changing roles in the course of the piece and all participants are equally involved in the narrative process.

The world premiere on January 24, 1958 in Basel , together with the performance at the 1959 Wiener Festwochen, was one of the composer's greatest successes.

Worldview and subject

The piece is about “questions of friendship, love and death”, so Martinů in his work commentary, which he introduces more generally with: “Despite the tremendous progress that we have made in technology and industry, I agree arrives that the feelings and questions that move people have not diminished, and that they exist in the literature of the oldest peoples (...) just as in ours. (...) In the epic about Gilgamesh, the desire to find answers to these questions is expressed intensely and with almost painful anxiety, the solution of which we seek in vain ... ”In his Epic of Gilgamesh , the overlapping of dream and reality is discussed. The seeker's dream anticipates reality and is intended to create a communicative bridge between humans and gods. Martinů stated that the choice of text was determined by the music. Bo Marschner concludes from this that it is therefore the composer's intention to only vaguely hint at a moment of action and to cover it up with lyrical elements. As a result, several important plot details are justified loosely and dramatically.

Martinů represented a progressive humanism that was based on Christianity. With his religious feeling, the composer was far removed from ecclesiastical formalism, and his sympathy was for Franciscan simplicity. In almost every one of Martinů's main works there is a moment when the sky opens, so Harry Halbreich reports on a statement made by the composer's wife, Charlotte Martinů. Halbreich explains more generally that Bohuslav Martinů was a staunch democrat and "a fierce enemy of any kind of dictatorship."

Martinů was a versatile reader of fiction as well as historical, sociological and scientific treatises. According to Halbreich, whose Alexis Sorbas he was enthusiastic about, he found his ethical and social views expressed in the work of Nikos Kazantzakis . While Martinů was working on his Gilgamesh epic in Nice , he even got to know the writer personally, who lived in Antibes , 20 kilometers away . At the suggestion of Kazantzakis, he decided at this time against setting Alexis Sorbas to music and instead for the project, Kazantzakis' extensive novel from 1948, Ο Χριστός ξανασταυρώνεται (German: Greek Passion ), a refugee drama, to set as an opera , from which The Greek Passion became. In his Gilgamesh epic , too, Martinů devotes himself to the artistic design of existential themes.

Text template and own text

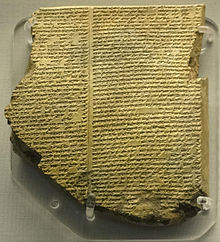

Martinů used an English translation of the Neo-Babylonian version of the Gilgamesh epic, which is called the Twelve Tables epic, as a template . This version was found in 1849 during British excavations in what is now Koujyundjik, then Nineveh , as part of the library of the Neo-Assyrian king Aššurbanipal (669 BC - 627 BC). Research in the British Museum in 1872 put the date of origin in the 12th century BC. Dated.

The text of the oratorio was written by Martinů himself in a free style, like the text template used in English. Marschner notes that Martinů designed all the scenes before the tragic turning point in the life of Gilgamesh as rather preliminary. For Martinů the myth is a prelude to philosophy and with an artistic revival of a myth, the supra-individual character becomes clear and only the essentials are exposed, says Jürgen Kühnel. Ines Matschewski sees Martinů's selection as “a new text variant of the myth”, and Martinů has also rearranged text passages. His selection leaves "the heroic deeds and adventures of Gilgamesh and Enkidu unnoticed." In this way, a subjective interpretation emerged, a rewrite. His biographer F. James Rybka describes it as "a sectional portrait of Gilgamesh in 3 parts." The first part of Martinů's work is based on panels 1 and 2, the second part is based on panels 7, 8 and 10, and according to the score According to the information in the score, part 3 is based on plate 12. There are some text passages that have been taken over in full, in others, according to Martinů Matschewski's results, "individual word groups from completely different contexts" have been regrouped. So some verses from the 9th table were incorporated into the 2nd part and in the 3rd part there are verses from the 10th and 11th tables. Martinů's text presents itself as “patchwork work”, Matschewski summarized the result of her analysis in 2012.

- Part 1 (401 bars), "Gilgamesh": The people describe the horrors of the ruler and ask the goddess Aruru to create a companion for Gilgamesh so that he is distracted; Aruru creates Enkidu; Gilgamesh found out about him through a hunter and had him brought into his sphere of influence through sexual seduction; Enkidu accepts the woman's suggestion and goes into town; Enkidus flock no longer wants to be with him and flees; Gilgamesh and Enkidu fight each other, the wall collapses.

- Part 2 (370 bars), “The Death of Enkidus”: The fight has ended, they become friends; Enkidu falls ill and dreams that he will die; he dies after twelve days of pain; Gilgamesh weeps very much for him; he seeks eternal life but cannot find it.

- Part 3 (525 bars), “The conjuration”: Gilgamesh has to realize that he was unable to learn the secret of immortality; Enkidu is to be brought back to life by an incantation; the only thing that succeeds is a conversation with his spirit, which can be heard at the end with: "Yes, I saw."

The work has a narrative style and is similar in form to a reading with assigned roles. In terms of content, two levels can be distinguished: on the one hand the plot and on the other hand philosophical considerations on life and death. The composer raised this to a generality by decoupling the statements from the individual figures who still appear as speakers in the epic model. In the first and third part, the actions and events of Gilgamesh and Enkidu are at the center of the action. The character of the second part, on the other hand, is shaped above all by the philosophical-contemplative sections, for which the two choral movements that frame Gilgamesh's lament act like pillars. The statements are presented as general wisdom, with Gilgamesh as the embodiment of the so-called man himself: with his inner conflict between fear and reason, his fears and memories of happier days as well as with the lamentation in the face of human impotence against death. Initially portrayed as a feared ruler, Gilgamesh becomes a fearful mortal.

The first two parts have final choruses, towards which the tension rises. In part 3, the incantation is initiated by recourse to the lamentation for the dead of the second part and ends with the appearance of Enkidu's ghost. Here the tension curve runs in a curve: ascending towards the conversation with Enkidus Geist and with a ebb at the end.

Text comparison

Jürgen Kühnel made a text comparison to show how the composer divided a passage into bass (narrator) and chorus, which in the English hexameter version by R. Campbell Thompson (1928) is narrated as one. Martinů reinforces the timeless interpretation of the myth by leaving out the ancient Mesopotamian names.

| R. Campbell Thompson Engl. 1928 |

Bohuslav Martinů engl. 1954 |

German version UE 12703 LW, 1957 |

| So when the goddess Aruru heard this, in her mind she imagined / Staightaway this concept of Anu, and, washing her hands, the Aruru / Finger'd some clay, on the desert she molded it: thus on the desert / Enkidu made she , a warrior, as he were born and begotten / Yea, of Ninurta the double, and put forth the whole of a fillet; / Sprouted luxuriant growth of his hair - like the awns of the barley, / Nor knew he people nor land; he was clad in a garb like Sumuquan. / E'en with gazelles did he pasture on herbage, along with the cattle / drank he his fill, with the beasts did his heart delight at the water. | BASS-SOLO: To th'appeal of their wailing Goddess Aruru gave ear. / She finger'd some clay, on the desert she molded it. / Thus on the desert Enkidu made she, a warrior. / In the way of a woman he snooded his locks, / sprouted luxuriant growth of his hair like the awns of the barley. | Bass: Aruru, the goddess, lent her willing ear to the cry. She now formed the clay earth in the lonely wasteland. So she created Enkidu, the bellicose hero. He wore his hair like a woman, and it sprout like barley in the field. |

| CHORUS: Nor knew he people nor land. / With the gazelles did he pasture on herbage. / Along with the beast did his heart delight at the water, / with the cattle | Chorus: He doesn't know people nor country. He tends to graze in the green with gazelles. United with the cattle, his heart urges for delicious water, like the herd. |

Composition and style

Musically, the work is characterized by great contrasts. Sound-intoxicating scenes in a large cast are juxtaposed with distinctive dialogues as well as an aftermath, "that breathtaking exploration of the last things, where the dying sounds finally merge with the silence of the infinite", so Halbreich. In his compositional style, Martinů uses different styles and subtly evokes joy and sadness. The dramatic action is reinforced by the contrast between sung and spoken language. Marschner sees the repeated use of spoken sentences almost as a symbol for something missing: In a programmatic way, context remains unfounded. Both the soloists and the choir take on changing roles over the course of the piece, and all participants are equally involved in the narrative process, emphasizes Matschewski.

The piece is composed for soloists, mixed choir and orchestra. The roles of the soloists are: soprano , tenor , baritone , bass and speaker. One female voice and four male voices are used. The voice of the speaker is not listed in the cast list and the names of the composer are inconsistent with regard to this part, and there are also ambiguities between the score and the piano reduction. Marschner sees the role of the speaker in accelerating the course of action by leaps and bounds. For example, the central moment of action when Enkidu decides to go into town lies with this commentator. Also contradicting are some instructions that provide for dialogic speaking between the soloists, which the compositional sentence ultimately does not allow, because the interrelationship between the actors has been greatly simplified compared to the text: There is no dialogue between Gilgamesh and Enkidu, the ruler leads later just a dialogue with its mind. In addition to strings, the orchestra mainly features trumpets and trombones, large drums, piano and harp and hardly any woodwinds.

Stylistic devices and techniques

The work as a whole is held together less by common motivic structures than by the fact that the musical material is presented in the introduction of a part. It is characterized by short-cut elements and motifs. The third part differs from the previous two in that it has an almost uniform motif.

In the entire work, the interval of the second , especially the small second, plays a decisive role as a motif component . At first it stands for people's fear of the ruler and from the second part on for the trepidation and agony of this ruler himself. Another characteristic is the use of the Moravian cadenza , a chorale ending with a distinctive transverse position , which can often be found in the composer's late works .

Matschewski explains that Martinů also uses composition techniques from the Paris Notre Dame School (around 1200) and modifies them. For the duel scene at the end of the first part, he was inspired by the old French Hoquetus . The fifth-octave closings are also a typical principle of this style epoch and can be found with its main master Pérotin . His influence on Martinů's typesetting system is great overall. Martinů generally does not imitate the stylistic devices and techniques of other masters true to the original, but rather embed them in a new framework, for example his choral movements exceed the boundaries of Pérotin and are rather free polyphony . Marschner almost reminds them of choirs by Carl Orff , he describes them as “irresistible and gripping.” In addition, the tonal range of the work, as is typical for Martinů, is expanded by elements from jazz and from film music.

Role of the choir

Martinů gave the choir special weight by continuously involving it in the entire oratorio. By varying the voice treatment, he succeeds in making a wide range of types of statements. As the piece progresses, the composer changes the singing style of the choir parts according to the different roles that he has given the choir. In the first part, depicting the plaintive people, his perspective in the seduction scene is transformed into an omniscient narrator , in which he is used almost instrumentally. In the second part, the choir alternately has the role of commenting on the events and then conveying the story again; quantitatively it is very present in this part. In the third part it is used again almost instrumentally during the incantation scene, after which it serves as reinforcement by adding an echo to Enkidu's answer. Kühnel sees the choir's variety of roles as being close to Greek tragedy .

Design of part 3

In part 3, Martinů creates tension by means of ostinati , says his biographer F. James Rybka. Matschewski describes it more as a basic rhythm that occurs as a component of rhythmic-melodic motifs and is constantly varied. Gilgamesh, Rybka continues, sings together with the choir, getting louder and faster, until it becomes a Presto together with the strings, piano and drums. The female voices of the choir imitate the wind to implore the god to let Enkidu rise from the earth. This is followed by a two-measure ostinato that is repeated eighteen times and ends in a dramatic scream. At this musical-dramatic climax, Gilgamesh's desperation is expressed using purely orchestral means, which suggests that the orchestra primarily embodies a quality of feeling, says Marschner. The earth opens and the answer from Enkidus Geist can be heard with "I saw." Matschewski emphasizes that this statement is more or less an epilogue to the brilliant eruption in the tutti and that it ebbs away unfinished in the morendo .

Origin and dedication

Martinů made plans for a larger choral work in Aix-en-Provence at the end of 1940. He had a great dramatic cantata in mind. The work is dedicated to Maja Sacher, who, together with the conductor and patron Paul Sacher, initiated such a format before the start of the Second World War. When Martinů visited the Sacher couple in 1948, they had brought a brochure about the Gilgamesh epic from the British Museum in London. In 1949 Martinů received the English translation of the Gilgamesh epic from Paul Sacher by the archaeologist and philologist R. Campbell Thompson ( The epic of Gilgamish , 1928). Martinů drafted his text in English.

Martinů created the composition between late 1954 and February 1955 in Nice. About the spring of 1954 in Nice , Charlotte Martinů wrote that her husband was “ fully occupied with the great composition of his Gilgamesh epic , a work that he carried in his head for years”, and further: “He read the epic again, in order to be able to decide which part he should set to music. ”A little later you can read:“ On Mount Boron he worked doggedly on his Gilgamesh epic . When he stepped onto the terrace, on which I used to spend most of the day, he said quite often: “This Gilgamesh is really hard on me.” “His biographer Miloš Šafránek writes that Martinů saw this material as old, Popular ideas, and Martinů was therefore pleased and surprised when Šafránek pointed out that Lubor Matouš's Epos o Gilgamešovi (1958) was a modern Czech translation, which was also much closer to the original in terms of metrics than the English Hexameter at Campbell. Šafránek continues: Martinů had passages from the Czech text sent to him for comparison purposes, especially panels I, XI (the Flood) and XII. But he said with regret that it was too late to use this text as a basis, because the work was almost finished. Ferdinand Pujman translated Martinů's text into Czech, using Matouš as a template. The text version in German comes from Arnold Heinz Eichmann.

It is true that the description of the Flood (plate 11) fascinated the composer most at the beginning, and when the cast was announced, a month before completion, he intended to set this theme to music as well, but it is not in the completed version more part of his interpretation of the myth.

Editions, duration of performance and question of genre

The premiere was delayed because initially no publisher could be found. The piano reduction and choral score were published by Universal Edition in Vienna in 1957 , the score in 1958. The performance takes about 50 minutes.

In research the work was initially classified as a cantata , but later the assessment seems to have prevailed that it belongs to the genre of the oratorio. For his form between oratorio and opera, the composer may have been inspired by Emilio de 'Cavalieri's Rappresentatione di Anima, et di Corpo , premiered in 1600. Martinů's later, semi-staged performance concepts, which point in the direction of opera, have not been implemented in most of the performances.

The Bohuslava Martinů Institute. ops, Prague has announced the complete critical edition of Martinů's works from spring 2015. The volume for The Epic of Gilgamesh will be among the first two volumes to be published.

Performances (selection)

- First performance in German: January 24, 1958, with Paul Sacher's Basler Kammerchor and the Basler Kammerorchester, conducted by Paul Sacher. In the first part of the concert there was another world premiere, Chain, Circle and Mirror - a symphonic drawing by Ernst Krenek .

- First performance in Czech: May 28, 1958 under the direction of Václav Smetáček as part of the Prague Spring.

- First performance of the original English version: April 18, 1959 under the direction of Sir Malcom Sargent in London.

Research literature

- Jürgen Kühnel: "Bohuslav Martinů's oratorio The Epic of Gilgamesh and Robert Wilson's theater project The Forest : Basic considerations on the subject of myth and the reception of myths - especially in music theater - using the example of two recent adaptations of the Gilgamesh material", in: Ancient myths in the music theater of 20th century. Lectures collected from the Salzburg Symposium 1989 , edited by Pater Csobádi, Gernot Gruber et al., Müller-Speiser, Anif / Salzburg 1990, ISBN 3-85145-008-6 , pp. 51-78.

- Bo Marschner: "The Gilgamesh epic by Bohuslav Martinů and the opera Gilgamesh by Per Nørgård ", in: Colloquium Bohuslav Martinů, His Pupils, Friends and Contemporaries: Brno, 1990 , edited by Petr Maček and Jiří Vyslouvžil. Ústav hudební vědy filozofické fakulty, Masarykova Univerzita, Brno 1993, ISBN 80-210-0660-9 , pp. 138–151.

- Ines Matschewski: "Questions of friendship, love and death: The Gilgamesh epic by Bohuslav Martinů", in: Texts on Choral Music: Festschrift for the tenth anniversary of the International Choir Forum ICF , edited by Gerhard Jenemann. Carus-Verlag, Stuttgart 2001, ISBN 39-230-5394-0 , pp. 41-47.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Harry Halbreich: Bohuslav Martinů - catalog raisonné and biography , [1968], 2nd, revised edition, Schott, Mainz 2007, ISBN 3-7957-0565-7 , pp. 454–457.

- ↑ Quotation in Ines Matschewski's translation from: Bohuslav Martinů: "Gilgamesch", in: ders .: Bohuslav Martinů. Domov, hudba a svět. Deníky, zápisníky, úvahy a články. Selected, commented on and edited by Miloš Šafránek, SHV, Praha 1966, p. 299f.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Ines Matschewski: "Questions of friendship, love and death: The Gilgamesh epic by Bohuslav Martinů", in: Texts on choral music: Festschrift zum tenth anniversary of the International Choir Forum ICF , edited by Gerhard Jenemann. Carus-Verlag, Stuttgart 2001, ISBN 39-230-5394-0 , pp. 41-47.

- ↑ a b c d e f g Bo Marschner: "The" Gilgamesh Epos "by Bohuslav Martinů and the opera" Gilgamesh "by Per Norgård", in: Colloquium Bohuslav Martinů, His Pupils, Friends and Contemporaries: Brno, 1990 , published by Petr Maček and Jiří Vyslouvžil. Ústav hudební vědy filozofické fakulty, Masarykova Univerzita, Brno 1993, pp. 138–151.

- ↑ Aleš Březina: “From› Experiments ‹,› Syntheses ‹and› Definitive Works ‹”, in: Aleš Březina and Ivana Rentsch , Ed .: Continuity of Change. Bohuslav Martinů in the history of music in the 20th century = Continuity of change. Bohuslav Martinů in the Twentieth-Century music history , table of contents (pdf,) Lang, Bern 2010, ISBN 978-3-0343-0403-0 , pp. 14–37, p. 14.

- ↑ a b Charlotte Martinů: Mein Leben mit Bohuslav Martinů , translated into German by Štěpán Engel, Orbis Press Agency, Prague 1978, p. 126/127, p. 129 and p. 131.

- ^ "Zeittafel", in: Ulrich Tadday, Ed .: Bohuslav Martinu , table of contents (pdf), Edition Text + Critique, Munich 2009, ISBN 978-3-86916-017-7 , p. 157

- ↑ Gabriele Jonte: Bohuslav Martinů in the US. His symphonies in the context of the years of exile 1940–1953 , table of contents by Bockel, Neumünster 2013, ISBN 978-3-932696-96-1 , pp. 225 and 245.

- ↑ a b c d e Jürgen Kühnel: “Bohuslav Martinů's oratorio The Epic of Gilgamesh and Robert Wilson's theater project The Forest : Basic considerations on the subject of myth and the reception of myths - especially in music theater - using the example of two recent adaptations of the Gilgamesh material”, in : Ancient Myths in Musical Theater of the 20th Century. Lectures collected from the Salzburg Symposium 1989 , edited by Pater Csobádi, Gernot Gruber et al., Müller-Speiser, Anif / Salzburg 1990, ISBN 3-85145-008-6 , pp. 51-78.

- ↑ a b c d e F. James Rybka: Bohuslav Martinu. The compulsion to compose , Scarecrow Press, Lanham, MD, 2011 Table of contents ( Memento of the original from November 7, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , ISBN 978-0-8108-7761-0 , pp. 258 and 259.

- ↑ a b Keith Anderson: "Bohuslav Martinů (1890-1959) The Epic of Gilgamesh", in: Supplement to the Naxos CD 8.555138, pp. 1-4, pp. 3-4.

- ↑ Šafránek quotes the composer's statement in quotation marks with: “folklore, some old folk concept”, p. 305.

- ↑ Miloš Šafránek: Bohuslav Martinů: his life and works , Wingate, London 1962, pp. 304-308.

- ↑ Catalog entry in the library of the Bohuslava Martinů Institute. ops, Prague

- ↑ Matschewski gives the following quote from Martinů from January 1955: "I La bataille de Gilgamesch, II La mort de Enkidu, III Le Déluge et l'invocation" (p. 41).

- ^ Catalog entry for the piano reduction (1957) at the German National Library

- ↑ Information from the institute by email.

Web links

- Recorded in Czech Bohuslav Martinů: The Epic of Gilgamesh (1954/1955). Wellesz Theater , youtube.com

- Catalog entry in the library of the Bohuslava Martinů Institute. ops, Prague

- Text of the work in German, based on the Czech version Lubor Matouš, which was repositioned by Ferdinand Pujman , klassika.info , last change on May 9, 2006, contribution by Engelbert Hellen. This text does not have the same words as the German text of the choral score of Universal Edition Vienna from 1957.