The Sinking of the Lusitania

| Movie | |

|---|---|

| Original title | The Sinking of the Lusitania |

| Country of production | United States |

| original language | English |

| Publishing year | 1918 |

| length | 12 minutes |

| Rod | |

| Director | Winsor McCay |

| script | Winsor McCay |

| production | Winsor McCay |

The Sinking of the Lusitania , full title The Sinking of the 'Lusitania', an amazing moving pen picture by Winsor McCay , ( German : The sinking of the Lusitania ) is an American animation and propaganda film by the cartoonist and comic artist Winsor McCay from the Year 1918 .

At the time of its publication, The Sinking of the Lusitania, with a running time of twelve minutes, was the longest animated film to date, although this was only true for the United States. It is the oldest surviving animated documentary and was inducted into the United States' National Film Registry in 2017 .

background

The Sinking of the Lusitania deals with the sinking of the passenger ship RMS Lusitania of the British Cunard Line by the submarine SM U 20 of the German Imperial Navy . The sinking of the Lusitania claimed 1198 lives among the 1959 people on board on May 7, 1915, 128 of whom were citizens of the neutral United States.

The international debate about the legality of the sinking of the Lusitania claimed by Germany was carried out with great propaganda effort. In the United States there was also the question of whether they should support the warring parties or even join the war themselves. With his film, Winsor McCay wanted to promote the entry of the USA into the First World War. McCay's employer, William Randolph Hearst, was a staunch opponent of US entry into the war, demanding anti-British and anti-war cartoons from McCay. Therefore McCay worked on The Sinking of the Lusitania in his spare time and financed the film - like his earlier films - with his own money.

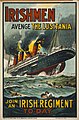

As a propaganda film, The Sinking of the Lusitania fits into a number of films and other products that pursued a similar objective. They were directed primarily against the Germans, who were addressed as barbaric Huns, and against the person of Emperor Wilhelm II. The sinking of the Lusitania and, at the beginning of 1917, the RMS Laconia were seen as the deliberate killing of civilians and as evidence of the inhumanity of the Germans shown. Contrary to what is often stated in the literature, The Sinking of the Lusitania was not the first animated propaganda film of the First World War. Examples of earlier films are The Peril of Prussianism by Leighton Budd , Me and Gott by LM Glackens and The Depth Bomb by E. Dean Parmelee , all from 1918. The sinking of the Lusitania has already been shown in real-life films, albeit without McKay's documentary claim shown earlier. In Her Redemption from 1916 and in Lest We Forget from January 1918, Rita Jolivet played with, who had survived the sinking of the Lusitania .

- Propaganda posters related to the Lusitania

action

In a live-action prologue of the signatory and director Winsor McCay is shown standing on a subtitle is referred to as the "inventor of the animated film" and has decided to draw a historical account of the crime that has shaken the world. McCoy has a Mr. Beach explain the course of the catastrophe to a picture of Lusitania . A subtitle indicates the number of 25,000 drawings for the film that had to be made and photographed individually. Finally, McCay is shown with a group of draftsmen working on "the first report on the sinking of the Lusitania ". The prologue ends with a representation of the waves on the sea, through which the periscope of a submarine moves, and an intertitle that describes the subsequent event as the first report of the sinking of the Lusitania .

The Lusitania leaves New York Harbor on May 1, 1915 with the destination Liverpool and passes the Statue of Liberty . The warnings from the German Embassy in Washington, DC , printed in the New York newspapers , are not taken seriously and the more than 2000 passengers (including more than 200 Americans) feel safe on board. The scene of the exit of the Lusitania ends with a stage curtain drawn from the right in front of the picture. A submarine, initially only shown as a tower jutting out of the water and then as a black silhouette with sailors on the upper deck, is sailing across the sea.

A subheading explains that the Lusitania comes within sight of the Irish coast at noon on May 7, 1915 . Two hours later, she is at a drive of 18 knots almost exactly beneath the bridge from the first torpedo of the German submarine U-39 hit. In the following animation sequence, the submarine appears and on its upper deck members of the crew wave, then they run to the tower, go below deck and the submarine dives. The Lusitania appears, and in front of her the periscope of the submarine. A torpedo runs underwater towards the Lusitania and detonates on her side, whereupon the ship catches fire.

Further subtitles name the number of 1150 fatalities, 114 of them Americans. Among them were world-famous personalities such as the philosopher and writer Elbert Hubbard , the actor and playwright Charles Klein , the entrepreneur Alfred G. Vanderbilt and the theater director and producer Charles Frohman , each of which is shown on a separate subhead with a portrait photo. Germany, according to a subtitle deposited by the imperial war flag , once a great and strong nation, had committed an insidious crime.

The Lusitania was launching her lifeboats when a second torpedo hit the engine room and "dealt the fatal blow" to the ship. Lifeboats crash when lowering and the Lusitania quickly listens, then she slowly sinks over the bow into the sea, and finally the Red Ensign disappears into the waves at the stern. Numerous desperate passengers rush over the railing into the water, including a woman who sinks into the sea and tries to keep her baby afloat until the end. After the Lusitania sank, a large number of people float between the lifeboats in the sea.

A final subtitle reads: The man who fired the shot was decorated for it by the Kaiser! AND YET THEY TELL US NOT TO HATE THE HUN (German: The man who fired the torpedo was honored for this by the Kaiser! AND BUT TELL US THAT WE SHOULD NOT HATE THE HUN ).

- Scenes from The Sinking of the Lusitania

Winsor McCay (left) and August F. Beach in front of a painting of Lusitania

Charles Frohman , one of the dead

The Red Ensign sinks last in the sea

Remarks

- McCay's claim to be the “inventor of the animated film” is purely an advertising statement, but he portrayed himself that way until the end of his life. It is indisputable that McCay shaped the American animated film in the 1910s.

- The "Mr. Beach ”is the journalist August F. Beach, who at the time of the sinking of the Lusitania was William Randolph Hearst's Berlin correspondent in London and was one of the first journalists to speak to survivors. The promotion for the film cited another expert, Lieutenant Commander JH Barnard of the US Navy , who had solved mathematical problems to make the representations in the film absolutely precise.

- The speed of the Lusitania of 18 knots was considered a protection against submarine attacks, as never before had a ship been torpedoed at a speed of more than 14 knots.

- The Lusitania was not sunk by the submarine SM U 39, but by SM U 20 .

- Only one torpedo was fired at the Lusitania . The cause of the second explosion is unclear, a dust explosion in the coal bunker as a result of the torpedo hit is considered likely.

- The motif of the woman drowning with her child was used in US propaganda shortly after the sinking of the Lusitania .

- Both the captain of SM U 20, Kapitänleutnant Walther Schwieger ( Iron Cross II. And I. Class, Knight's Cross of the Royal House Order of Hohenzollern with Swords, Pour le Mérite ) and his watch and torpedo officer Oberleutnant zur See Raimund Weisbach (Iron Cross II and I class, Friedrich-August-Kreuz , U-boat war badge ) received high awards from 1916. A direct connection between the award and the sinking of the Lusitania has not been proven and is unlikely. Weisbach was only awarded the EK II after he had received his own command.

- The Hun (in the singular) was a term used in anti-German propaganda for the German war machine or the German people and for their outstanding personalities, especially the Kaiser. The name goes back to the 1900 by Wilhelm II. During the adoption of the China expedition to put down the Boxer Rebellion held Hunnenrede back.

Production notes

The RMS Lusitania was the largest passenger ship in the world for two months in 1907, then it was replaced by its sister ship the RMS Mauretania . Winsor McCay was enthusiastic about the Lusitania and made the ship part of the plot in the September 27, 1907 episode of his comic strip Dream of the Rarebit Fiend . A little later, on October 15, 1907, the main character Mr. Bunion of the comic strip A Pilgrim's Progress by Mister Bunion called the Lusitania "the monster ship that broke the record". For Mr. Bunion , in particular , McCay used opportunities to link his character to real events and thus bring them closer to the reader. The maiden voyage of the Lusitania a few weeks ago was such an occasion.

McCay had drawn his earlier successes Little Nemo (1911), How a Mosquito Operates (1912) and Gertie the Dinosaur (1914) lavishly on rice paper . With The Sinking of the Lusitania , McCay used the much more effective method of working with cels for the first time . This allowed a limited number of templates to be drawn for elements such as backgrounds or the sea, which repeatedly appeared in the same shape throughout the film, while a large number of complete drawings had to be made beforehand. Compared to later cels, those used by McCay and his coworkers had very strong material and tended to curl. Fitzsimmons therefore developed a method that made it easier to place them on top of each other and take pictures. The cels received perforations on the lower edge, with the help of which the elements of a picture were clamped precisely one above the other in a ring binder. Its lid had an opening through which the overall picture was photographed.

Working with Cels was not only an innovation that made the production of animated films more efficient, it also had a significant impact on the quality of the film. As the number of cels placed on top of one another increased, the film appeared lifeless, in contrast to McCay's earlier work on rice paper. The same sequences of the backgrounds appeared monotonous. The distributor's advertising, on the other hand, emphasized the largely flicker-free presentation compared to earlier animated films.

During the work on The Sinking of the Lusitania , William Randolph Hearst founded his International Film Service in December 1916 , which was to produce animated films. Winsor McCay appeared on a published list of illustrators, but in fact he never worked for the IFS. However, Hearst forced a contract change in February 1917, with which McCay was awarded a significantly higher salary, but was also prohibited from any outside activity. The public screening of his animated films was an essential aspect of McCay's work, from which he drew creative energy. A second creative mainstay were his comic strips, some of which he published under a pseudonym. Hearst demanded neither one nor the other for his newspapers, but rather political cartoons that corresponded to his convictions.

Work started in 1916 and lasted 22 months. While McCay worked as a cartoonist for newspapers during the day, he devoted himself to work on The Sinking of the Lusitania in the evenings . Two of his collaborators can be identified by name, his neighbor John Fitzsimmons, who had also worked on Gertie the Dinosaur , drew sixteen pictures of the waves for the background, which formed a continuously repeated cycle. Cincinnati cartoonist William Apthorp "Ap" Adams has been McCay's main contributor to several films. For The Sinking of the Lusitania , he put the Cels in the right order for the recordings that were made at Vitagraph Studios .

In the United States, the film was filed with the Copyright Office on July 19, 1918 and first screened the following day. McCay's goal of supporting the USA's entry into the war with his film was missed because the war had already entered the previous year. In Great Britain, The Sinking of the Lusitania was first performed in May 1919.

The film is a one-reeler on 35mm film 900 feet in length . The 25,000 frames specified by McCay were questioned; at a frame rate of 18 frames per second, the film would be 26 minutes long. A plausible explanation is that the specification of 25,000 images referred to cels, several of which, placed on top of one another, result in a single image of the film.

With The Sinking of the Lusitania Winsor McCay could not build on his earlier successes. After several years in the cinemas, the film brought in only 80,000 US dollars, which is 3.20 US dollars per image for the specified 25,000 images. McCay produced at least six animated films in the following years. Three of these films ( The Centaurs , Flip's Circus and Gertie on Tour ) have only survived in fragments, three more are animations of his successful comic strip series Dream of the Rarebit Fiend .

More than 300 cels have been preserved from Gertie the Dinausaur . The few surviving cels from The Sinking of the Lusitania , mostly with the signature of Winsor McCay, are the only other existing cels of his films and achieve high prices on the collector's market.

criticism

From The Sinking of the Lusitania any contemporary reviews or audience reactions have survived. However, the film was aggressively promoted by Universal Studios in their industry magazine The Moving Picture Weekly , other magazines, and on billboards. The film was marketed by Universal in its premium line Jewel Pictures, which shows that it is of great importance to the company. The advertisement highlighted that Jewel Pictures had raised the highest price ever paid for a one-reeler for the worldwide performance rights to The Sinking of the Lusitania . The film is remarkable for three reasons: as the first animated film with serious content, it reports without any glossing over the crime that shook the world, and it is the first short film acquired by Jewel, worthy of together with Jewels' patriotic films The Kaiser, the Beast of Berlin and The Man Without a Country .

The film was considered to be technically outstanding work, but it had no major influence on the animated films produced after it. As one reason, his biographer John Canemaker cited that McCay's skills were beyond what the contemporary draftsman could achieve. It was not until the great Walt Disney films of the 1930s that The Sinking of the Lusitania was able to surpass The Sinking of the Lusitania in technical terms. In addition, documentary animations were mostly only subordinate components of real films, and pure animation films were almost always comedies.

As in his earlier animated film Gertie the Dinosaur , in which McCay combines the drawn dinosaur with real-life scenes of himself, in The Sinking of the Lusitania he uses his presence in the introduction to influence the audience. His claim that the film is the first documentary of the sinking of the Lusitania cannot be realized due to the lack of any photographic material. But his introductory appearance, with a contemporary witness and the image of Lusitania , gave his subsequent drawings an authenticity in the eyes of the contemporary viewer that was equivalent to that of photographs and real films.

The film historian Paul Wells described it as a significant moment in the history of animated film, how The Sinking of the Lusitania combines almost documentary elements with a pronounced propagandistic objective. In this extraordinary combination, the film follows the contradictions of the modern age and it makes the animated film a medium of modernism.

Wells' colleague James Latham sees The Sinking of the Lusitania as unique for its time because of its hybrid shape. Like McCay's biographer John Canemaker, Latham sees the difference from most documentaries in that it is an animated film. Unlike most animated films, it is not a comedy. In addition, The Sinking of the Lusitania is notable for being one of the first films to use the cels' new technique in making it. Although The Sinking of the Lusitania received no contemporary reviews, Latham considers it to be one of McCay's most significant films.

The Sinking of the Lusitania was advertised as the longest animated film of its time. This statement has also been adopted in the literature on film history. In fact, the animated film El Apóstol by director Quirino Cristiani, which was released in Argentine cinemas on November 9, 1917, was significantly longer with a running time of 70 minutes. In 2017, The Sinking of the Lusitania was inducted into the United States' National Film Registry .

- Advertisement for The Sinking of the Lusitania

Web links

literature

- John Canemaker: Winsor McCay. His Life and Art , 3rd edition. CRC Press (Taylor & Francis), Boca Raton 2018. ISBN 978-1-138-57887-6

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c John Canemaker: Winsor McCay , pp. 194-196.

- ^ A b John Canemaker: Winsor McCay , pp. 215-217.

- ^ A b James Latham: 1918 - Movies, Propaganda, and Entertainment . In: Charlie Keil and Ben Singer (eds.): American Cinema of the 1910s. Themes and Variations . Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick et al. 2009, ISBN 978-0-8135-4444-1 , pp. 204-224, here pp. 217-218.

- ^ A b John Canemaker: Winsor McCay , pp. 203-205.

- ↑ a b c Anonymous: "Sinking of the Lusitania" will be released by Jewel . In: The Moving Picture Weekly June 29, 1918, Vol. 6, No. 20, p. 10 and p. 34, digitized .

- ^ Kirsten A. McKinney: The Waking Life of Winsor McCay: Social Commentary in A Pilgrim's Progress by Mr. Bunion . In: International Journal of Comic Art 2015, Vol.17, No. 1, digitized .

- ^ A b John Canemaker: Winsor McCay , pp. 201-203.

- ↑ John Kundert-Gibbs and Kristin Kundert-Gibbs: Action! Acting Lessons for CG Animators . Wiley Publishing, Indianapolis 2009, ISBN 978-0-470-22743-5 , pp. 46-47.

- ^ A b c John Canemaker: Winsor McCay , pp. 205-207.

- ↑ a b Bill Mikulak: Mickey Meets Mondrian: Cartoons Enter the Museum of Modern Art . In: Cinema Journal 1997, Vol. 36, No. 3, pp. 56-72, JSTOR 1225675 .

- ^ John Canemaker: Winsor McCay , p. 267.

- ^ Tom W. Hoffer: From Comic Strips to Animation: Some Perspective on Winsor McCay . In: Journal of the University Film Association 1976, Vol. 28, No. 2, pp. 23-32, JSTOR 20687319 .

- ^ Daniel McKenna: Impression and Expression: Rethinking the Animated Image Through Winsor McCay . In: Synoptique - An Online Journal of Film and Moving Image Studies 2013, Vol. 2, No. 2, digitized .

- ^ Paul Wells: Animation and America . Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick 2002, ISBN 0-8135-3159-4 , pp. 33-34.

- ^ John Canemaker: Winsor McCay , p. 268.