Theories of stone transport during the construction of the Egyptian pyramids

There are many theories about stone transport during the construction of the Egyptian pyramids . To this day it is not clear how the heavy stone blocks with an average weight of 2.5 tons were moved and piled up during the construction of the Egyptian pyramids . There are and have been numerous disputes between scientists and engineers about how this achievement could be achieved logistically and technologically. Many of the theories put forward about pyramid building have been refuted, but none can be considered conclusively proven. Each of the theories proposed must be checked to see whether it can also explain the transport of the ceiling slabs, which can weigh up to 40 tons, for the grave vaults inside the pyramids.

Ramp theories

All ramp theories assume that the stone blocks were pulled on wooden sleds or over rollers by workers or cattle. To reduce the friction resistance of the sledges, lubricants or rollers were used under the runners. There are ancient Egyptian images showing such sleds, which are pulled on ropes by many workers (on a horizontal plane) and transported stone statues with an estimated weight of up to 50 tons. The principle of rolling friction between two surfaces with balls or fine-grain sand, which is much lower than sliding friction, was known in ancient Egypt.

A study published in 2014 showed that water as a lubricant in the right amount reduces the necessary pulling force by half and that the sand does not have any braking effect.

In 2018, scientists near Hatnub discovered the remains of a ramp in one of the alabaster quarries there , which made it possible to transport stones and thus support the ramp theory.

Straight outside ramp

The ramps have just been brought up to the building level of the pyramid and, as the pyramid grew, they were also continuously built upwards.

Against this theory speaks the fact that the length of the ramp with a 10% incline at the Cheops pyramid would have had a length of about 1.5 kilometers and that more material would have been required for its construction than for the pyramid itself.

Internal and external ramps

A combination of internal and external ramps made it possible to easily transport the stone slabs of the burial chamber, weighing up to 50 tons, and other stones for the pyramid parts above. A straight external ramp only had to be led to a height of one third of the total height to reach the burial chamber. Around 80% of the stone material for the pyramid is used at this height. It can be assumed that the ramp was built with the missing 20% stone material. This was gradually dismantled as the building height increased so that the ramp material could be used as a building material for the upper part of the pyramid. Ramps from sand dumps are therefore not likely. In the upper section of the building, the ramps were created within the pyramid volume and lastly filled in from the top to the grave chamber level.

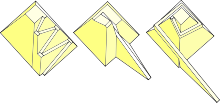

Tangential ramps

Due to the structural damage that occurred during the construction of the pyramids of Snefru in Meidum and Dahshur, a different construction method was used in the fourth to sixth dynasties: Instead of the layers joined together, the structures consist of a stepped core that was then clad.

In order to achieve the shortest possible construction time for the pyramids, stones had to be transported on all four sides at the same time. This was possible with tangential ramps arranged parallel to the outer surfaces. The stones could be pulled up over these ramps with an incline of 2: 1 (24 °). The train crew ran down a flight of stairs.

The complete procedure for building a pyramid using this method was first published in 2011.

Spiral ramp

The spiral ramps were built along the outside of the pyramid. Since they partly used the already finished pyramid as a substructure, they needed relatively little building material of their own and could be dismantled after completion of the pyramid.

Tunnel theory

The tunnels represent a modification of the spiral-shaped ramps, in which the ramps are located inside the pyramid (thus leaving tunnels or inner ramps free), which are filled from top to bottom after completion of the pyramid construction. Jean-Pierre Houdin assumes that the stones were transported along a tunnel inside the pyramid. This ramp had grown continuously and led upwards in a spiral form below the four outer sides. The corners of the pyramid were open and the stones could be turned there. With this assumption, the huge amounts of building material that would have been necessary with the alternative side ramps or a ramp winding around the pyramid are omitted. Archaeological evidence will be sought on site.

Elevator theory

Using sledge-like means of transport, each stone cube was dragged upwards in a cage over a ramp made of solid Nile mud on the outside of the pyramid, while at the same time a cage with a counterweight, which was connected to the load cage by ropes and pulleys, slid down on a parallel track next to it . Human workers were used as a counterweight. When the load cage with the stone reached the top level, the workers climbed back up to act as a counterweight for the next stone. To simplify work organization when moving to the next higher building level, there were elevators on different pyramid sides. In the upper regions of the building, the counterweight elevator was no longer placed on the same side of the pyramid, but on the opposite side of the pyramid due to a lack of space, so that the deflection points were omitted.

In this theory, the much heavier granite blocks for the roofing of the burial chambers were already in a very early stage on the unfinished pyramid and were moved from one building level to the next by means of levers and support structures, for example by means of many small lever operations and subsequent relining or via short ramps promoted.

Vertical elevator

A variant of this theory is a counterbalanced elevator with two vertical shafts that were located near the center of the pyramid base. The shafts were reached from the outside via tunnels, which were later closed again. From a certain height onwards, the pyramid was built as a tower with vertical side walls in order to always have a sufficient working surface. The tower (which could also be built from smaller stones) was dismantled after the pyramid was completed. The Egyptologist Christine El Mahdy has dealt with old sources on this topic and favors the construction via shafts over all ramp theories.

Winch / pulley theory

The cable winch theory is a modification of the elevator theory in which the counterweight of the elevator is replaced by cable winches that are turned by humans or animals. The use of pulley blocks could have reduced the force required to lift or drag the elevator cages. The pull could have been exerted from the pyramid base via pulleys, without pulleys the workers or draft animals would have had to pull on the building level.

Crane theory

The blocks of stone were placed in baskets, which were moved from one level to the next by cranes on each pyramid level. The cranes were arranged so that they could pass the blocks from one level to the next. The crane worked like a beam scale with a load basket and a counterweight basket. People who climbed into the second basket served as a counterweight. Once at the top, the balance beam was rotated around its support until the stone block could be put down. The workers, who acted as counterweights, now hung outside the pyramid and left the cage via a down rope or a gangway. The next crane picked up the cage and carried it on. Instead of the beam balance construction, lifting jacks with pulling devices can also have been used.

What speaks against the elevator and crane theories is that no anchoring has yet been found for such devices in or on a pyramid. However, these could also have been closed again later with stones pushed in.

Stair theory

Herodotus reports that the covering stones were finally smoothed, from top to bottom. They are previously “graded like stairs or like steps or altar steps”. If Herodotus is to be believed, the pyramid flanks were initially designed as stairs and thus made accessible for a large number of construction workers and auxiliary workers at the same time. A facing stone can, for. B. have three steps of 24 cm, which are chiseled off at the end of construction, so smoothed. (Pyramids with existing external stairs are known from Central America). In some places on the flanks the steps are missing, so that upward gutters are created that serve as smooth guides for the sledges with the stone blocks. On both sides of the channel there is enough space for larger pulling teams on many ropes, who can safely stand on the steps, in order to pull approx. 20 kg upwards per man without moving upwards themselves. The substitute team can be changed on the fly. In an emergency, the slide can be tilted at any point in the channel so that it inhibits itself and does not cause a catastrophe. The staircase theory thus represents a special case of ramp theories in which the pyramid flank itself functions as a ramp.

The gutter is kept slippery; it is not entered, but crossed on a plank. The stairs serve as a wide supply route for teams, tools and water as well as for the removal of accident victims, who undoubtedly existed. Putting on the pyramidion is made technically possible by the four tapering stairs at the top.

Since there is no visual obstruction due to auxiliary structures, the constant re-measurement of the structure explains the extraordinary precision of the structure as a whole. The first use as a way out explains the high cost of the cladding.

Combination theories

Construction techniques that represent a combination of the theories mentioned are conceivable. So it is possible that the pyramids were supplied with stones up to a certain height via ramps, e.g. B. up to the height of the burial chamber ceilings in about 50 meters, which corresponds to a built pyramid volume of about 80%. Then one of the other transport methods described was used for the other stone blocks.

See also

literature

- Dieter Arnold : Building a pyramid. In: Lexicon of Egyptian architecture. Artemis & Winkler, Zurich 1997, ISBN 3-7608-1099-3 , pp. 202-204.

- Mohammed Z. Goneim: The Lost Pyramid. Eggers, Norderstedt 2006, ISBN 3-8334-6137-3 .

- Zahi Hawass : The Treasures of the Pyramids. Weltbild, Augsburg 2004, ISBN 3-8289-0809-8 .

- Christian Hölzl (ed.): The pyramids of Egypt. Brandstätter, Vienna 2004, ISBN 3-85498-360-3 .

- H. Illig and F. Löhner: The construction of the Cheops pyramid. 3rd edition, Mantis, Graefelfing 1998, ISBN 3-928852-17-5 .

- Peter Jánosi : The pyramids. Beck, Munich 2004, ISBN 3-406-50831-6 .

- Erich Lehner: Paths of Architectural Evolution - The Polygenesis of Pyramids and Step Buildings. Aspects of a comparative architectural history. Phoibos, Vienna 1998, ISBN 3-901232-17-6 .

- Mark Lehner : Secret of the Pyramids. Bassermann, Munich 2004, ISBN 3-8094-1722-X .

- Frank Müller-Römer : On the building of the pyramids in the Old Kingdom . In: Göttinger Miszellen No. 220, 2009 ISSN 0344-385X , pp. 61-70.

- Frank Müller-Römer : The construction of the pyramids in ancient Egypt . Utz Verlag Munich, 2011, ISBN 978-3-8316-4069-0 .

- Corinna Rossi: Pyramids and Sphinx . Monuments of Egyptian culture. Belser, Stuttgart 2005, ISBN 3-7630-2265-1 (popular science, easily readable overall presentation with numerous descriptive illustrations).

- Rainer Stadelmann : The Egyptian pyramids. From brick construction to the wonder of the world (= cultural history of the ancient world . Volume 30). 3rd, updated and expanded edition. Philipp von Zabern, Mainz 1997, ISBN 3-8053-1142-7 .

- Rainer Stadelmann: The great pyramids of Giza. Academic Printing and Publishing Company, Graz 1990, ISBN 3-201-01480-X .

- Miroslav Verner : The pyramids (= rororo non-fiction book. Volume 60890). Rowohlt, Reinbek bei Hamburg 1999, ISBN 3-499-60890-1 .

Web links

- Architecture of the pyramids

- Combination of different ramps (PDF file; 117 kB)

- A method of building a pyramid in which wooden pulleys were anchored directly to the pyramid flank

- Internal spiral ramps

- Theories on the construction technology of the Great Pyramid

- Frank Müller-Römer: Building a pyramid with ramps and winches: A contribution to structural engineering in the Old Kingdom. Dissertation, LMU Munich: Faculty of Cultural Studies (2008)

- Transporting large stone blocks in ancient Egypt [1]

- Basic considerations and statements about the construction of the pyramids in the old kingdom [2]

- Search for pyramid in the SPK digital portal of the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation

Individual evidence

- ↑ F. Müller-Römer: The construction of the pyramids in ancient Egypt . Utz Verlag Munich, 2011, ISBN 978-3-8316-4069-0 , Chapter 4.3.3 Stone transport on the straight and inclined plane, pp. 103-112.

- ^ A. Fall, B. Weber, M. Pakpouretal .: Sliding Friction on Wet and Dry Sand. In: Physical Review Letters. No. 112, Article 175502, Published 29 April 2014, DOI: 10.1103 / PhysRevLett.112.175502 .

- ↑ Archeology: Evidence Discovered: The Great Pyramids were built with ramps . In: Der Standard , November 6, 2018, accessed November 7, 2018.

- ↑ F. Müller-Römer: The construction of the pyramids in ancient Egypt . Utz Verlag Munich, 2011, ISBN 978-3-8316-4069-0 , Chapter 8.2 The individual construction phases, pp. 362–389.

- ↑ Interview with Frank Müller-Römer In: Bild der Wissenschaft March 19, 2008 - Archeology - "Most common building proposals cannot work like this"

- ↑ Cheops pyramid built from the inside out? In: Adventure archeology . Vol. 3, 2007 ( epoc. 03/07 ), Spektrum, Heidelberg 2007, ISSN 1612-9954 .

- ↑ H. Illig, F. Löhner: The construction of the Cheops pyramid. 3rd edition, Mantis-Verlag, Graefelfing 1998, ISBN 3-928852-17-5 .

- ^ Rainer Stadelmann: The Egyptian pyramids. From brick construction to the wonder of the world (= cultural history of the ancient world. Vol. 30). von Zabern, Mainz 1985, ISBN 3-8053-0855-8 , pp. 217 to 226.

- ^ Rainer Stadelmann: The great pyramids of Giza. Graz 1990, pp. 247 to 274 → Chapter 6: Building a pyramid.