Thingstätte (Heidelberg)

The Heidelberger Thingstätte ( ) is a in the era of National Socialism supposedly ancient modeled after Greek Theater as Thingstätte built outdoor stage on the Holy Mountain in Heidelberg .

The laying of the foundation stone for the “Thingstätte Heidelberg” took place on May 30, 1934 and on June 22, 1935 it was opened by Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels under the new name “Feierstätte Heiligenberg” . But she played a significant role in the rapidly becoming meaningless thing movement . After the facility lay fallow in the post-war years , occasional events were held there later and the designation as "thing site" was generally used again. Until 2018 it was mainly used for unofficial Walpurgis night celebrations . The complex is a protected cultural monument.

history

prehistory

In the first years after the seizure of power by the Nazis, and as part of the Nazi cultural propaganda, the Thing movement emerged. It was their objective to “... shape and create the new German people according to the will of the Führer from the community experience”.

Construction planning

The facility on the Heiligenberg was conceived as the central location of the Thing movement and Heidelberg, as “a Salzburg of the German south-west ”, was to help National Socialism gain recognition worldwide. The old Heidelberg Festival (1926–1929) was to be revived with the planned Thingstätte, but now under Nazi patronage. The name "Reichsfestspiele" was invented and, beginning in 1934, such games were used ideologically under the Reich Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels. However, the idea of turning Heidelberg into “a Salzburg of the German south-west” originated substantially from the time of the Weimar Republic . The city was tried to be propagated as a "cosmopolitan city of the spirit", as a "living breath of the German soul" or as a "focal point of the imperial concept" and thus ideologically inflated. Heidelberg thus became the "City of the Reich Festival". In 1934 these were staged for the first time in the inner courtyard of Heidelberg Castle , intended to initiate a “revolution in German theater” and to become “representative witnesses of the new conception of art”.

As a student town , a former study town and favorite town of Goebbels, which has been respected since the Middle Ages , it had good prospects of being awarded the contract for the monumental building project. In those years it was given the title “Place of pilgrimage”, which clearly shows the importance of Heidelberg as a central location for the “Reichsfestspiele”. When choosing the location for the Thingstätte, comparisons with other cultic sites in geographical proximity were used. B. Heidelberg Castle , Speyer Cathedral and Worms Cathedral . In addition, the local proximity to the Ehrenfriedhof Heidelberg , begun in 1934 , because it offered the opportunity to form a unit with the new cult site by instrumentalizing fallen soldiers from the First World War . Overall, this promoted the decision in favor of Heidelberg as a location. The exaggerated cult of the dead of the Nazi era found expression in these places. The castle ruins, which are in sight, were seized for propaganda purposes “for the greatness and tragedy of the German past” (press documents June 20, 1935). In connection with the alleged "ancient Ahnenerbe", a meeting place was constructed on the Heiligenberg, the architectural design of which was based on the Germanic " Thing ", an open-air public meeting place, which cannot be specified. In this context, the legendary Heiligenberg with the Heidenloch and the many prehistoric remains of settlements was chosen as the ideal location for such a thing site.

The Thingstätte should then be completed according to plans by the architect Hermann Alker . In its basic concept, it was designed as a unit with the Heidelberg Ehrenfriedhof on the Ameisenbuckel , a mountain range on the other side of the Neckar and the castle in between.

Function in the Nazi era

The Nazi ideology is often referred to in their media as "faith" in connection with the national community they are striving for, and the Thingstätte as a place of homage and practice of that "belief". Accordingly, for example, a headline in the newspaper Heidelberger Volksgemeinschaft in 1935 reads : “The Thing as a cult site of the National Socialist faith”. The Thingstätte can thus be regarded as a “holy” place and a planned exercise site of the Nazi “faith”. The sacred design of the Nazi building can be seen as an expression of the National Socialist "faith". Many features of the thing place manifest and support the intended appearance as a sacred place.

The Nationalblatt reported in March 1935 in connection with the Thingstätte in Koblenz , which had been created in a hectic and ruthless manner on the forecourt of the Electoral Palace , that economic value and high costs were not allowed to play a role and explained this with a "deep sense" of the Thing sites:

“In principle, the labor service only carries out such work, the economic value of which is perfectly established and which would not have to be carried out because of excessive costs if it were to be undertaken through the free economy. Since the labor service has been under purely National Socialist leadership, this principle has always been adhered to. The Reichsleitung des Arbeitsdienst approved one exception: the building of the Thingplatz. That has a deep meaning. The Thingplatz should become the home of a new folk culture and folk art that emerged from the National Socialist creative power. ”Quotation: Nationalblatt (Kreuznach district) March 1935

Dirk Zorbach from the University of Koblenz analyzes a different meaning in the thing buildings. He emphasizes that through extensive propaganda and with mystical-ritual festivals and celebrations, an attempt was made to establish a political substitute religion. In addition, the Nazi hero cult always had to be present at such places. In general, with the instrument of the thing movement and in connection with an allegedly ancient ancestral heritage, attempts were made to bring largely obscure Germanic legal traditions out of oblivion and to convert them into a mass event according to their own ideological ideas. Basically, the term "thing" goes back to a Germanic, judicial form of assembly. However, depending on the region and historical context, the meaning of the word has changed frequently and blatantly. The Germanic "Thing" or "Ding" was a people, army or court assembly, presided over by a king, tribal or clan chief, which took place in the open air. The course of a "thing" is described in Germania (Tacitus) . Since the early modern period , it has received a lot of attention and in this way developed a considerable broad impact. More recent research regards the work as thoroughly critical and points to the problematic history of its reception. In Franconian times , the "thing" only referred to the court, an assembly of legal comrades chaired by a judge. Thing sites in the “Third Reich” were built to “educate and discipline” the “new German people”, who were to be transported there through artistic and representational means. The audience was intentionally included in these events in order to do justice to the propaganda goal of merging the people into the National Socialist community. The Thingspiele and theater pieces - better described as cultic spoken chorus dramas - represented Nazi ideology visually and acoustically. In Heidelberg from 1935 to 1939, these pieces were performed annually at the Reich Festival.

In the Nazi media, a great ideological benefit of the Thingstätten movement was always asserted, from which the various labor services as well as the Thingstättenbau benefited equally. By building cultural and political infrastructure in monumental form, which promised to be widely publicized beyond the national borders, the Nazi regime tried to pretend peacefulness. The more and more paramilitary labor services in the structures - especially those of the later RAD - should conceal this with their participation. The reason for the war preparation, especially the six-month mandatory service for the RAD, which was generally introduced in 1935, and the also introduced conscription - which preceded this - should be deceived with projects that seem as harmless as possible.

Laying of the foundation stone

The foundation stone was laid on May 30, 1934 by Robert Wagner (Gauleiter) and Lord Mayor Carl Neinhaus . The Heidelberg mayor emphasized the mythical meaning of the “holy mountain” in his celebratory speech and saw in figurative language the “red, blood-colored sandstone [...] the popular place of new seeing and hearing grow”.

So-called “Thingstättenweihen” had a special cultic meaning and were also referred to as “people becoming celebrations”.

Construction work and strike

With the support of the Heidelberg student body, over 1,200 labor service men were temporarily building on the site. The plans come from the Karlsruhe university professor Hermann Alker and the final design was an amphitheater with 8,000 seats and around 5,000 standing places, two hexagonal flag towers for lighting and sound and wide ramps for choir, players and spectators, for example.

As a result of a test print of the architectural drawing - which may be based on a drawing by the architect - a semicircular stage and cloakroom building should complete the shell-shaped complex, in which, as the main difference to the Greek amphitheater, the playing area and auditorium are not separated by a large, separate scene building. This should create a community between performers and people. In the form of an egg-shaped open-air theater, it should have a capacity - in the original design - 10,300 seats and space for a further 20,000 standing places, with a dance ring behind the stage. Work began in April 1934 and should be completed by July. However, this project was canceled as impracticable and it was continued with a reduced plan. The architectural design of this cult site was basically continued with the usual features of fascist architecture such as monumentality and objectivity. The total construction costs, including the creation of parking and access roads as well as the provision of water and electricity, were likely to have been around RM 600,000, all but RM 40,000 being borne by the city. The participation of workers of the Reich Labor Service (RAD) was operated mainly for propaganda purposes. Most of the work was done by professional builders. In Alker's original plan there was no electronic acoustic amplification: The building in which the electronic amplifiers and the rear part of the stage - in which the actors' changing rooms were to be housed - were still missing in the plans. Previously only a high visual barrier should be built there, which should also reflect an echo from the audience. In early thing sites like this one, however, especially in that of the Brandberge near Halle , the good overall acoustics of the ancient Greek amphitheater were not given. The open-air theater in Heidelberg was therefore now planned with 8 microphone lines fed by 17 stage microphones, plus 7 loudspeakers at the edge of the stage and on the stage building, which was supposed to be lower than originally planned and also provided with ramps on both sides. It was planned as an additional stage area. Now, for example, the entire open-air theater could be surrounded by a long line of flag-bearers or torch-bearers. Two towers at the rear of the system and at the top of the grandstands housed the controls for the sound and lighting, including a mixer. The electrical installations should enable the playing of sound recordings and the transmission of radio broadcasts on the stage, as well as the acoustic amplification of stage actors who appeared important for the performance of thingspiel dramas. The plans for the Thingstätten on the Loreley and in the Barnstorfer Wald (Rostock) were modified based on the acoustic experience with the Thingstätte Heidelberg.

On the Heiligenberg, irreparable damage to the remaining historical legacy occurred during construction. The work centered on the middle of a large Celtic settlement in the middle of a double ring wall that was partially preserved . The rocky subsoil had to be partially made usable with blasting. Although shards of Celtic origin have been found, archaeological evidence has not been documented.

The planned 400 smaller thing venues with five to ten thousand spectator capacity were to be built in the German Reich in the following years. However, the thing movement subsided as early as 1936 - in the end, 66 such systems were built. A more precise date for the start of construction is unclear. The Voluntary Labor Service (FAD) came to work in April 1934 at the earliest. Its activities were characterized by the " national labor battle ", as the " synchronized " media portrayed at the time. The so-called “ Voluntary Labor Service ” worked in two, later in three shifts, each for one Reichsmark wage per day. The service set up a field trolley for earthmoving, but without a tractor - only with tipping wagons that had to be pushed.

Completion of the complex was planned for the solstice celebration in 1934. Due to the rocky subsoil, however, there were delays. The opening ceremony therefore only took place on June 22, 1935. Before that, the emergency workers who were also employed in the construction of the Thingstätte went on strike . The political exile magazine Deutschlandberichte of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (Sopade) reported: “ In the last week before the completion of the Thingstätte in Heidelberg there was a kind of strike in the form of passive resistance. The emergency workers apart from the labor service should work at night without extra pay. They asked for a 30 percent wage supplement, which was rejected. The workers then refused to work at night. After three nights they were granted the 30 percent. “The Germany reports of the Sopade were founded on the basis of an extensive network of informers from the Reich and represent an important and uncensored source of information for everyday life and the attitude of the population towards the regime in Nazi-ruled Germany.

Bad planning and effects

From 1931 to 1935 Konstantin Hierl was head of the voluntary labor service of the NSDAP . After the "seizure of power" he was appointed State Secretary in the Reich Ministry of Labor in March 1933 and the following year he was appointed Reich Commissioner for Voluntary Labor Service . When compulsory labor service was introduced on June 26, 1935, Hierl took over the management of the newly created Reich Labor Service (RAD) as “Reich Labor Leader” . The work on the many and sprawling thing sites in the German Reich was under great deadline pressure. In addition, the plans revised in 1934 provided for ten to twenty spectator seats, with increasing technical difficulties for which many skilled workers from the private sector had to be called in. The labor service was overloaded early on. In addition, many emergency workers had to be deployed. The use of the latter groups was downplayed by the Nazi propaganda and the ideological impact of the Reich Labor Service in creating the National Socialist national community was exaggerated. Goebbels therefore explicitly praised the Reich Labor Service in his opening speech on the Heiligenberg .

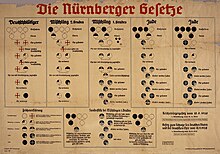

As early as 1934, Hanns Niedecken-Gebhard was chosen to be the director of the pilot production of a game of things in the open air: Richard Euringer's German Passion (1933), audio work in 6 movements. It was supposed to play in the first representative thing site as part of the “Heidelberg Reichsfestspiele”. The work was about a nameless undead soldier who unites the divided population into a "national community". His task was to translate the previous audio work not for a radio program, but for the stage and into visually representable movement. The Thingstätte am Heiligenberg was still under construction at the time. Due to this bad planning, he had to switch to the well-known Heidelberg Schlossplatz as a venue. The performance, which was planned as a mass theater, was confined to the smallest of spaces. His career as a thing game director was already over at the start. In general, the game of things cannot be said to have failed because the ritual of allegiance in various forms was already installed in everyday life. The ruling apparatus was already consolidated, for example: Nuremberg Laws . The cultic moment of the “national community” was passed anyway.

Niedecken-Gebhard played a key role in the development of the things game in the 1930s. He developed the basics of the things game from his preoccupation with the operas of Georg Friedrich Handel in the course of the “Handel Renaissance” in the 1920s. He later staged the opening ceremony of the 1936 Summer Olympics , which also included the Things Games . In the immediate aftermath he was director of the monumental festivals in Breslau and Munich .

Use in the Third Reich

In the 56 rows of spectators, which rise 25 meters at an angle, allegedly 20,000 people found space at the opening, the system was designed for significantly less. The semicircle of the “celebration site” was opened on June 22, 1935 by Propaganda Minister Goebbels. This was the only time that the seats were fully occupied. It was traditionally a day for solstice celebrations. Goebbels stated in his address:

» In this monumental building we have given our style and our view of life a lively, sculptural and monumental expression. [...] These places are actually the parliaments of our time. [...] The day will come when the German people will walk to these stone sites in order to confess their immortal new life in ritual games. «

After twelve months of construction and thus nine longer than initially planned, Goebbels, at the inauguration during a solstice celebration, ideologically exaggerated the complex as the “true church of the empire” and site of “National Socialism turned into stone”. It was alleged that the Thingstätte was built on an allegedly Germanic cult site, with which it was passed off as part of the Nazi blood-and-soil mysticism. The stage should primarily be used for propaganda events. In the following years there were some performances of things like "The way into the kingdom" or "The oratorio of work". However, the National Socialists soon lost interest in the system, as radio was a more effective tool for spreading propaganda. Until 1939, festivals at the solstice continued to be staged, whereby the highly technical equipment for the time with a sound mixer , loudspeaker system and headlight lighting is particularly worth mentioning. In 1939 the Heidelberg City Theater performed Schiller's Bride of Messina . So-called "folk celebration and consecration hours" were celebrated here. These were anything but harmless summer open-air theater: marches and mass rallies in the open air, plus ideological “thing games” were supposed to contribute to re-education into a “new German man” - under strict control by the new rulers. The Heidelberg Thingstätte is evidence of the adaptation and alienation of the historical idea by the Nazi regime. Instead of focusing on an allegedly historical gathering and discussion of matters, the basic structure of the Thingstätten built under the National Socialists - as in Heidelberg - enabled the cult of the Führer to be staged through their structurally central location .

A call from the district leadership of the NSDAP, which was issued after the game "Weg ins Reich", when visitors tried to get to safety from a rainy squall, illustrates the "new image of man" of the Nazi ideology by quoting some formulations:

" It was very instructive to see how (...) many people from the country put their little 'I' back into the center of their existence when the first raindrops fell and dark clouds darkened the sky."

An impending mass panic was indeed perceived, but the stewards were only asked to:

“ (...) to make it clear to the individual that the new dress and the beautiful hat, and even the risk of a possible cold, are not so important. ".

The phrase “'I' people and cowards have no place in a thing site!” Was tellingly used twice in the appeal.

The system in Heidelberg was considered exemplary by Nazi leadership circles and as a model for comparable buildings, including the ones that still exist on the Loreley , the Bad Segeberger and Dietrich Eckart stages in Berlin. The installed sound and light system in particular was considered a marvel of technology. This was admired by experts from home and abroad. The opening ceremony with a forest of flags, a large contingent of uniformed people, music and a huge choir was already the record for the audience. This number was no longer reached at later solstice celebrations and things games. In terms of its mass effectiveness, the entire thing movement also generally fell short of expectations. Basically, the specially created new genre, the Thingspiele, and their lengthy and monotonous mixes of choir and “ passion plays ” were not able to permanently attract the audience. In addition, the adversity of the inconsistent weather and the lack of protection against it often made the events unpopular and posed problems for the Nazi organizers. But in principle the envisaged ritual unification of “national comrades” in the open air in places with a powerful Germanic past did not fit into the concept of a dawning “new age”, which was presented as progressive. Thus, the Nazi propaganda gradually lost interest in the pseudo-Germanic thing movement.

During the Second World War, the facility was largely unused. As early as 1936, the name “Thingstätte Heidelberg” was changed to “Feierstätte Heiligenberg” by decree. Previously the scene of things games, flag consecration of the Hitler Youth, theatrical performances and other propaganda events, the functional history as a site of "National Socialism turned to stone" ended with the erection of an anti-aircraft tower in 1942.

Use in the post-war period

After the Second World War , the Thingstätte , which was signposted as a celebration site, was largely abandoned. For a number of years, the US community in Heidelberg held its Easter sunrise celebration at the Thingstätte or youth or sports groups met there.

The facility is now a listed building . It used to be used for open-air concerts (e.g. opera performances, concerts by Udo Jürgens, Placido Domingo, Montserrat Caballé), even if the area is not easy to manage due to the difficult infrastructure (lack of sanitary facilities, difficult access, etc.).

From the 1980s to 2017, a celebration without an organizer took place annually on Walpurgis Night , which became the largest unofficial celebration in Heidelberg . On the night of May 1st, thousands of people recently moved to the Heiligenberg and celebrated a festival at which there were neither commercial stalls nor electric lights. The city is forbidden to enter the facility at night due to liability reasons, but it was tolerated. Police, fire brigade and THW usually allowed a larger fire as well as fire breathers who displayed their skills. Furthermore, the THW Heidelberg was turned off for the emergency lighting. In the days that followed, enormous amounts of rubbish covered the site. In some years up to 20,000 people attended the celebration. In December 2017, the city of Heidelberg banned upcoming Walpurgis night celebrations due to the forest fires that had previously been triggered by visitors and the necessary rescue of the injured.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f g h The Thingstätte on the Heiligenberg ( Memento from December 30, 2019 in the Internet Archive ) on zum.de, January 2003.

- ↑ Oliver Fink: Little Heidelberg City History , Friedrich Pustet Verlag, Regensburg, 2005, p. 114.

- ↑ Oliver Fink: A Salzburg of the German southwest? Castle Festival in Heidelberg . In: Heidelberger Jahrbuch zur Geschichte der Stadt , ed. vom Heidelberger Geschichtsverein, 6/2001, pp. 61–77.

- ↑ Oliver Fink: 'Little Heidelberg City History', Friedrich Pustet Verlag, Regensburg, 2005, p. 116.

- ↑ a b c d e f Thingstätte Heidelberg Why the Nazis built the Thingstätte , on rnz.de

- ↑ Newspaper, Volksgemeinschaft: The Thing as a place of worship for the National Socialist faith , June 22, 1935.

- ↑ a b c d March 24, 1935. Inauguration of the Thingstätte in Koblenz , on landeshauptarchiv.de

- ↑ Dirk Zorbach: "Our Leader ..." - The National Socialist Propaganda as a Substitute Religion using the example of festivals and celebrations in Koblenz ; in: Yearbook for West German State History 2001 (Volume 27); Koblenz 2002, pp. 309-372.

- ↑ Shadows on the Heidelberg Myth - On the Trail of the National Socialists , on scienceblogs.de

- ↑ Kiran Klaus Patel: “Soldiers of Work”: Labor Services in Germany and the USA 1933–1945 , Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2003, p. 315.

- ↑ a b Rainer Stommer, The staged national community: the "Thing" movement in the Third Reich , Marburg Jonas, 1985, pp 211th

- ↑ Rainer Stommer, The staged national community: the "Thing" movement in the Third Reich , Marburg: Jonas, 1985, p 107th

- ↑ Rainer Stommer, The staged national community: the "Thing" movement in the Third Reich , Marburg: Jonas, 1985, p 108/10.

- ↑ Series of publications on the landscape, culture and history of Heidelberg: The Heidelberger Thingstätte, the Thingstätten movement in the Third Reich: Art as a means of political propaganda , p. 68.

- ↑ Series of publications on the landscape, culture and history of Heidelberg: The Heidelberger Thingstätte, the Thingstätten movement in the Third Reich: Art as a means of political propaganda , pp. 72–73.

- ^ Reports on Germany by the Social Democratic Party of Germany (Sopade) , July 2, 1935, Klaus Behnken (ed.), Nördlingen, publishers: Petra Nettelbeck / Zweausendeins, 1980, p. 787.

- ↑ Kiran Klaus Patel: “Soldiers of Work”: Labor Services in Germany and the USA 1933–1945 , Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2003, pp. 313–315.

- ↑ Katja Schneider: The noise under the choreography: reflections on "style" , Narr Francke Attempto Verlag, 2019, pp. 59–61.

- ↑ Bernhard Helmich: Handel Festival and "Game of 10,000". The director Hanns Niedecken-Gebhard (= European university publications , series 30: theater, film and television studies , vol. 32), dissertation, Frankfurt am Main [among others]: Lang, 1989.

- ↑ Heidelberger Volksblatt , June 24, 1935, No. 144.

- ↑ Compare: Martin Heidegger: Lectures and Essays (1936–1953) . Ed. Günter Neske Pfullingen 1954, p. 173.

- ↑ Nadine Schwalb: Heidelberg dances into May. (No longer available online.) In: face2face. May 8, 2015, archived from the original on October 28, 2016 ; accessed on October 28, 2016 .

- ↑ Heidelberg: City forbids Walpurgis Night celebration on the Thingstätte . ( rnz.de [accessed December 7, 2017]).

literature

- Rainer Stommer: The staged national community. The "Thing Movement" in the Third Reich. Marburg, Jonas 1985, ISBN 3-922561-31-4 .

- Wolfgang von Moers-Messmer: The Heiligenberg near Heidelberg. Its history and its ruins. Published by the Schutzgemeinschaft Heiligenberg e. V. 3rd, updated and expanded edition. Brausdruck, Heidelberg 1987.

- Emanuel Gebauer: Fritz Schaller. The architect and his contribution to sacred buildings in the 20th century (= city traces. Monuments in Cologne. Vol. 28). Bachem, Cologne 2000, ISBN 3-7616-1355-5 (including dissertation, University of Mainz 1994 under the title: The Thing and the Church Building. Fritz Schaller and Modernism 1933–1974 ), contains chapters on the construction of the Thingstätten at the beginning of National Socialism.

- Oliver Fink: Time travel through Heidelberg. Excursions into the past (= series of publications by the Heidelberg City Archives. Special publication No. 16). Published by Peter Blum on behalf of the city of Heidelberg. Wartberg-Verlag, Gudensberg-Gleichen 2006, ISBN 3-8313-1583-3 , pp. 68-69.

Web links

Coordinates: 49 ° 25 ′ 24 ″ N , 8 ° 42 ′ 23 ″ E