Unrest in Iran in June 1963

In June 1963 there was in Iran to unrest. In the course of the political conflict, on June 5, 1963 (according to the Iranian calendar : 15th Chordad 1342 ) the Hodschatoleslam Ruhollah Khomeini was arrested and a state of emergency was declared. This day was seen by Khomeini and his followers as the beginning of the Islamic Revolution and is now a day of remembrance in Iran.

The unrest initially concentrated in the cities of Tehran and Qom and was led by clergy and merchants of the bazaar. The protest, which later spread to other cities, was directed initially against the government of Prime Minister Asadollah Alam and later against Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi . It resulted in violent clashes across the country between the security forces and the demonstrators. With the protests supported by the Nehzat-e Azadi ( Iranian Freedom Movement ) around Mehdi Bāzargān and Ayatollah Mahmud Taleghani , a member of the party alliance of the National Front , the reform program of the White Revolution of Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, above all the abolition of large landed property , was intended as part of the framework a land reform and the introduction of women's suffrage be prevented.

background

The starting point was the protest organized by Khomeini against the social changes promoted by Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi in Iran, the effects of which were already apparent in the course of 1962. Until then, Iran was not very industrialized. Economic power was in the hands of large landowners and religious foundations. From the time of the Qajar originating feudal structures were still largely intact. After a visit to the USA and extensive discussions with President John F. Kennedy, Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi set himself the goal of modernizing Iran through a comprehensive reform program, abolishing the old feudal structures, disempowering religious foundations and making Iran a modern one To reshape industrialized state.

On July 19, 1962, Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi appointed Amir Asadollah Alam as Prime Minister. Alam was himself one of the largest landowners in Iran and should set a shining example. The White Revolution, as Alam's predecessor, Prime Minister Ali Amini, called the reforms, had started with land reform . The reform program, which was also called the “revolution of the Shah and the people”, had a further thrust: In addition to the abolition of large landed property, the political rights of all citizens and, above all, the rights of women were to be strengthened.

The opponents of the reforms, the large landowners and the Shiite clergy, quickly found each other and began to organize resistance against the reform projects. The clergy were affected in two ways: They were largely financed by the income of religious foundations, which had huge land holdings that they had leased to farm workers. An “expropriation in favor of the farm workers in return for financial compensation”, as envisaged in the white revolution, would have ended the long-term security of their financial income. Strengthening the political rights of Iranians, in particular legal equality for women, would have meant a further elimination of the Sharia case law, as it has been anchored in Iranian civil law since the legal reform of Justice Minister Ali-Akbar Davar in 1928. Accordingly, Khomeini branded the reform plans as directed against Islam from the start.

The financial means for building a resistance movement came from the ranks of the big landowners and merchants of the bazaar, who saw their import monopolies threatened by the industrialization of the country. The resistance movement received political support from the National Front , which expressed solidarity with the clergy in opposition to Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi.

The 1962 reform of local electoral law

The first clash between the government and the clergy occurred on October 7, 1962. Prime Minister Alam's cabinet had passed a decree to bring local suffrage into line with democratic standards. Women should have the right to vote and stand for election. In addition, the class suffrage introduced in Iran with the Constitutional Revolution in 1909, which divides voters according to their religious affiliation into electoral classes, and provides for the election of representatives according to the religious groups of Muslims, Christians, Jews and Zoroastrians recognized by the constitution, should be abolished at the local level become. With the reform of the electoral law, local elections in Iran should be general, direct, free, equal and secret, and thus fully meet democratic standards.

The decree met with fierce opposition from the clergy. For one thing, she considered it incompatible with Sharia law that women should vote or be elected to public office. She also contradicted the abolition of class voting rights. Clergymen were particularly angry about a formulation of the new electoral law that concerned the swearing-in of elected city councilors. The formula of the oath should be taken on "a holy book". With the abolition of class suffrage , the Baha'i who were opposed by the Shiite clergy could have been elected and sworn in on their Kitab-i-Aqdas .

The Ayatollahs Mohammad Reza Golpayegani , Kasem Schariatmadari and Haeri as well as Hodschatoleslam Ruhollah Khomeini decided to contact the Shah directly so that he could influence the government to withdraw the decree. If that does not happen, they face serious consequences. The Shah informed the clergy that he understood their concerns and wanted to refer them to the government. This positive reaction from the Shah reinforced the clergy in their criticism of the government. Khomeini now attacked Prime Minister Alam personally: "If you violate the laws of Islam, the constitution and the laws passed by parliament, you will be held personally responsible." This statement amounted to a death threat. The assassination of Prime Minister Hassan Ali Mansour in 1965 showed that this was not an empty threat . Just a few days after Khomeini's speech, violent clashes broke out with security forces in Fars province , during which a provincial official was killed by demonstrators.

On November 29, 1962, Prime Minister Alam relented and declared that women would not participate in the upcoming local elections. The right to choose classes would also be retained as before. As before, the swearing-in should take place "on the Koran, the Bible, the Torah and the Avesta". The clergy had fully enforced their demands and were more than satisfied with this victory.

The White Revolution begins

During 1962, Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi made speeches in all the provinces of the country in which he introduced the principles of the White Revolution . He had previously published his ideas about the further development of Iran in a book entitled “In the service of my country”. In a speech in Tehran that the Shah gave on the occasion of his birthday on October 26, 1962, he called the White Revolution “a social transformation” that has never happened in Iran's 3,000-year history: “These reforms are intended for everyone Equal rights for citizens. ”In Mashhad he declared:“ Those who work in the fields will no longer be vassals from now on . They will be free men who will receive fair wages for their work. "

On January 9, 1963, the Shah opened the National Congress of Peasants of Iran and explained the six basic principles of the White Revolution to 4,200 delegates:

- Abolition of the feudal system and distribution of arable land from large landowners to farmers

- Nationalization of all forests and pastures

- Privatization of state industrial companies to finance the compensation payments to the large landowners

- Profit sharing for workers and employees of companies

- universal active and passive voting rights for women

- Fight against illiteracy by building an auxiliary teacher corps ( army of knowledge) .

The Shah announced that there would be a referendum on January 26, 1963 on the principles of the White Revolution, in which the people of Iran could freely vote on the program presented by the Shah. The delegates present unanimously approved the proposal by Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi to hold a referendum. The question of the referendum had previously been discussed controversially in the cabinet. The Iranian constitution did not provide for a referendum, and the only referendum that had ever been held in Iran was held by Mohammad Mossadegh , who, after dissolving parliament, let the people of the country grant him the right to hold the country until further notice to govern by decree. The referendum of Mossadegh represented a clear breach of the constitution. For this reason, the population should be consulted with the approval or rejection of the political program of the White Revolution. The legal framework of the White Revolution was then later to be implemented through laws that Parliament had to pass. In this way, the referendum did not lead to the disempowerment of parliament, but to a constitutionally compliant reform process.

The popular vote of January 26, 1963

On January 22, 1963, four days before the vote, Khomeini declared the referendum illegal and a blasphemy. He urged all Muslims not to take part in the vote. Khomeini had recognized that the Shah could override the constitutional veto of laws by means of a referendum through a five-member committee of the clergy. Referendums were not legally binding, but created such high political pressure that no one could have opposed the majority opinion of the Iranian people. As a result, Khomeini's supporters organized demonstrations against the referendum. The merchants in the bazaar in Tehran were pressured to close their shops. There were first clashes between demonstrators and the police.

On January 23, 1963, the government announced that it would not allow the vote to be disrupted. On the same day, farmers came to Tehran who, together with workers from the state industrial companies, had organized a demonstration for the Shah's reform program. Women had organized a demonstration in which they asked to take part in the vote. Officials and ministries' teachers went on strike to back up their demand to take part in the referendum.

On January 24, 1963, the Shah went to Qom , where a real war had broken out between the students of religious schools and the police. In his speech in Qom, the Shah attacked Khomeini directly, referring to his ties to the Muslim Brotherhood :

“We have eliminated the free riders in this country who lead their lives at the expense of others. We have lifted your mask. For me, the black reactionaries are far worse than the reds. ... This gentleman Khomeini, whose ideals embody the Nasser government of Egypt, who bought arms for more than a thousand million dollars and proposed that we disband our armed forces. We have made landowners out of 15 million farmers, while the model of this gentleman is the Egyptian Gamal Abdel Nasser , who rules over 15,000 political prisoners and does not allow elections or a parliament. "

On the evening of January 25, 1963, the government announced that women could also vote. However, their votes would be collected separately from those of the men in separate ballot boxes.

The vote on January 26, 1963 was largely peaceful. At around 11 a.m. it was announced on the radio that the women's votes would be counted, but their votes would not be added to the voting result. At the time of the count, 16,433 women in Tehran and almost 300,000 women in the provinces cast their votes for the reforms. For men, the result was 521,000 in Tehran and 5,598,711 votes in the provinces for the reforms. Contrary to all fears, the women were able to cast their votes without any problems. Many went to the voting booth with their husbands. The result of the vote showed that the men supported their wives and agreed to their right to vote.

As the first result of the referendum, on February 27, 1963, the Shah declared that women had the right to vote and stand for election. Parliament amended the electoral law accordingly.

The New Year celebrations

In his New Year's address on March 21, 1963, the Shah commented in detail on the result of the referendum. He stated that the future development of Iran is based on social justice. The wealth of the country should benefit all citizens. Income from labor and capital should be fair and lawful. Every citizen should receive a minimum income that ensures him a decent life.

Khomeini said that this year the population could not feel happy about the beginning of the new year, since the reforms that the Shah had put to the people for a vote were directed against Islam and that the whole referendum was a criminal act . In addition, he declared the vote to have failed because a maximum of 2000 people had taken part.

On April 1, 1963, the Shah made a pilgrimage to Mashhad at the end of the New Year celebrations . In a speech he criticized Khomeini and the National Front:

“The good Muslims of Iran must be made aware of the real intentions of the Koran. You have to recognize as wrong the rules that were invented by some individuals to fill their own pockets. ... There are two groups that are against our policies: there is the black reaction and the red traitors. We have robbed the red traitors of their arguments (through our reforms). You have lost your bearings and were speechless. Like parrots, they repeat what they have been taught without reference to real developments. "

Chronology of events

June 3rd - The Ashura Festival

On June 3, 1963, during the Ashura celebrations , Khomeini personally attacked the Shah in a speech at Ghom's Faizieh School by delivering a speech against the tyrant of our time . In this speech, alongside the Shah, Khomeini for the first time not the USA but Israel at the center of his criticism:

“This government is directed against Islam. Israel is against the fact that the laws of the Koran apply in Iran. Israel is against the enlightened clergy ... Israel is using its agents in this country to remove the resistance against Israel ... Oh Mr. Shah, oh exalted Shah, I give you the good advice to give in and forsake [these reforms]. I don't want to see the people dancing for joy on the day when you will leave the country by order of your masters, as everyone cheered when your father left the country. "

June 4th - Protesters storm Radio Tehran

On the morning of June 4, 1963, well-organized demonstrations with up to 10,000 participants broke out in Tehran, which soon turned into violent attacks against the police. The demonstrators tried to storm the Radio Tehran building, but they did not succeed. Army weapons depots were attacked and police stations looted. Police and fire brigade cars were set on fire in central Tehran. There were deaths both among the police who tried to stop the demonstrators and among the demonstrators.

June 5th - The arrest of Khomeini

After these events, Khomeini was arrested on June 5, 1963 (15th Khordad). The arrest took place at 4 a.m. Khomeini was taken from his home in Qom to the officers' club prison in Tehran. Mostafa Khomeini, Khomeini's son, immediately informed all neighbors that his father had been arrested. He went to the Masoumeh Mosque and announced over the loudspeaker that Khomeini had been arrested. At the same time as Khomeini, Ayatollah Qomi in Mashhad and Ayatollah Mahalati in Shiraz were arrested and taken to Tehran.

Police chief and military governor of Tehran, Nematollah Nassiri , called General Gholamali Oveisi at 5 a.m. to keep his troops ready. At 9 a.m. the news that Khomeini and several other ayatollahs had been arrested had reached the bazaar in Tehran. Khomeini supporters used bicycle and motorcycle couriers to inform the bazaar dealers that they had to close their shops. Anyone who did not want to comply was threatened.

Students from Tehran University took to the streets and shouted: "Free Khomeini". At around 9:30 am, around 2,000 people from the bazaar had gathered on the street for a demonstration across from the Seyyed Azizollah mosque. Slogans like "Death or Khomeini" were shouted. Teyeb Haj Rezaie from the vegetable bazaar organized another demonstration. The demonstrators armed themselves with sticks, knives and iron pipes. Farmers from Varamin, Kan, Jamaran and other villages around Tehran joined the demonstrators from the bazaar. The march of demonstrators moved into the city center in the direction of Radio Tehran. The buildings of the Iran-American Society, Pepsi-Cola and some banks, as well as the Justice Department were stormed and set on fire. Telephone booths and benches along the way of the demonstration train were smashed. A particular target was the sports club of Schaban Jafari, who played a major role in the fall of Mohammad Mossadegh in 1953 . The sports club was set on fire.

A group of protesters moved towards the Marble Palace, where Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi's office was located. Suddenly rifles were distributed among the demonstrators and there were first shootings with the police. With shouts like “Either death or Khomeini” - “Down with the blood-drinking dictator”, the demonstrators made it clear that they were determined to do everything and that their aim was to overthrow the Shah. As on the previous day, private vehicles, police cars and fire engines were set on fire. Across from the radio building there were violent shootings with many wounded and dead, both on the part of the demonstrators and the security forces. Prime Minister Alam responded promptly. A state of emergency has been declared in Tehran. There was a curfew from 8 p.m. Prime Minister Alam had called the army for help after he had only been able to leave the seat of government in an armored vehicle. Troops marched in the streets of Tehran. There were further exchanges of fire between the demonstrators, the security forces and the army soldiers.

In the village of Pishva, Varamin, it was announced over loudspeakers that Khomeini had been arrested. The men went to the public bath, washed, put on white robes as martyrs, and went to Tehran. They were armed with sickles, axes and knives. On the bridge to Bagherabad, soldiers met the demonstrators who asked them to turn back. The demonstrators attacked the officer in charge with a knife and wounded him, which resulted in an exchange of fire. The result was some wounded demonstrators.

June 6th - More ringleaders are arrested

On the night of June 5-6 , other clergymen, including Ayatollah Mahmud Taleghani , and bazaar merchants who had participated as leaders of the demonstrations, were arrested. General Hassan Pakravan , head of SAVAK , gave the press an initial interview in which he named some mullahs who had allied themselves with "dirty elements from abroad" as the culprits in the violent clashes.

The following day, June 6, 1963, Prime Minister Alam said in a radio address that the demonstrations instigated by the clergy had been suppressed and the ringleaders had been arrested. He revealed to the population that the demonstrations were not a spontaneous protest movement, but a deliberate attempt to overthrow. The demonstrators' plan was to cut off the water supply, the switchboard and the power supply in Tehran in the coming days and to take over the radio station Radio Tehran.

There were further demonstrations in Tehran during Alam's address. The demonstrators tried again to storm the radio station in Tehran. There was another exchange of fire. There were also further demonstrations in Qom. Cinemas, shops, police cars and buses were set on fire.

June 7th - The clergymen's council meets

On June 7, 1963, Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi declared: “Numerous demonstrators who have been wounded or arrested have told the police that they have given us 25 rials to shout:“ Long live Khomeini ”. We will uncover the background to these demonstrations and punish those responsible. ”Prime Minister Alma announced at a press conference that 15 religious leaders had been arrested and were being tried before a military tribunal. Alam made it clear that those responsible would be held accountable and that there could be death sentences if necessary. Everyone involved in the demonstrations now realized at the latest that the attempted coup had failed and that the government would crack down on it. It was also clear that Khomeini, who was primarily responsible for the demonstrations, was in danger of being sentenced to death and executed.

In this threatening situation for Khomeini, Ayatollah Kasem Shariatmadari went from Qom to Tehran to organize the rescue of Khomeini. He called on the clergy from Mashhad and other cities to come to Tehran and campaign for the release of Khomeini. On the same day, 50 clergymen arrived in Tehran, including Najafi Marachi , Hossein Ali Montazeri and Ali Akbar Hāschemi Rafsanjāni . They decided to send an envoy to Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi to clarify how things were going with Khomeini. Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi assured the envoy Ruholla Kamalvand that Khomeini would not be executed because they did not want to make a martyr out of him: "We will, however, reveal his true character to the population." could visit in custody. As it quickly turned out, Khomeini was in excellent health. The bazaar merchants, who had been on strike since Khomeini's arrest, reopened their shops and the political situation slowly began to normalize.

June 8 - The Prime Minister's Government Statement

On June 8, 1963, Prime Minister Alam issued a government statement in parliament in which, as in the previous press releases, he justified his tough stance towards the demonstrators in front of the MPs: "If we had not reacted in this way, we would have accepted that the country would have fallen into the hands of the mullahs. "

June 9th - Mehdi Bazargan's press release

Mehdi Bazargan issued a press release in which the number of those killed and wounded indicated more than 10,000 people.

“You Muslim nation of Iran, you know that the uprising of the high clergy and other mullahs was directed against the cruelty of the ruling system and against the dictatorship. In no way is this holy struggle directed against reforms. "

As later investigations after the Islamic Revolution showed, "only" 234 people died in all incidents between opposition members and the security forces from 1963 to 1979. The exact number of dead of the 15th Chordad is still controversial. The information varies between 20 and 40 people. With the number of people killed in the demonstrations of the 15th Chordad, the attempt was made to blame the government for the violence that occurred during the demonstrations.

June 25 - Khomeini is transferred to a military prison

Khomeini is being transferred from the officers' club prison in downtown Tehran to the Eshratabad military prison outside Tehran.

July 20 - Most clergymen arrested are released

On July 20, 1963, the majority of the clergymen arrested, including Sadegh Khalkhali and Falsafi, as well as some merchants who had participated in the uprising, were released.

Campaign for the release of Khomeini

The plan of Mozaffar Baqai

After the attempted coup had failed, it was now a matter of limiting the damage to those responsible. The most important goal was to get Khomeini out of prison. The Khomeini family contacted an old acquaintance, Mozaffar Baqai , the leader of the Labor Party and former minister of Mossadegh. Baqai developed a strategy how to put pressure on the Alam government and get Khomeini free. One only has to turn the Hodschatoleslam Khomeini into an ayatollah and ideally the supreme ayatollah, a Marja, then he would be invulnerable to the government. Baqai believed that the Alam government would never dare to take legal action against the country's highest cleric.

The Khomeinis family seems to have agreed with this proposal, because Baqai wrote an open letter to all Ayatollahs on Tir 15, 1342 (July 6, 1963):

“The Central Committee of the Workers' Party assumes that Prime Minister Alam's government only wants to hold off the clergy and calm them down in order to be able to convict Khomeini in a secret trial. She wants to force the high clergy to beg for mercy for Khomeini. The government wants the clergy to accept that Khomeini must be punished in compensation for the blood spilled during the uprising, and that the only way to avoid execution is to obtain a pardon. In order to neutralize these black government plans, Khomeini must be designated Marja Taqlid and the highest of all Shiite clergy at home and abroad without any ifs or buts and free from any criticism of his previous behavior. "

This demand from Baghai initially met with little approval from the three highest clergy from Qom. Firstly, Khomeini was only Hodschatoleslam; secondly, according to Baqai's suggestion, he should not only be elected for a spiritual rank from Hodschatoleslam to Ayatollah, but also to Marja Taqlid and the highest of all clergy, quasi Pope of all Shiites. Baqai accused all clergymen who opposed his proposal of contesting Khomeini for the role of Supreme Leader out of personal envy.

Khomeini becomes Ayatollah and Marja Taqlid

Baqai now contacted numerous ayatollahs and asked them to ask Khomeini an exam question and then appoint him to ayatollah without much discussion. Ayatollah Mohammad Taqi Amoli, who lived in Tehran, immediately took action and declared that he recognized Khomeini as ayatollah and the supreme leader of all clergy. It was followed by Ayatollah Mohammad Hadi Milani from Mashhad on July 6, 1963. One day later, on July 7, it was Ayatollah Kasem Shariatmadari and Ayatollah Shahab al Din Marashi Najafi who recognized Khomeini as Ayatollah and supreme leader. Ayatollah Mohammad Reza Golpayegani , the highest-ranking Ayatollah to date, steadfastly refused to recognize Khomeini as an Ayatollah.

After a fatwa was issued in favor of Khomeini that from now on he would be Ayatollah and Marja Taqlid, Baqai went one step further. In a publication he referred to Section 17 of the Press Act of Iran of August 2, 1954. Section 17 relates to the offense of insulting Marja Taqlid: “If an article or text appears in a newspaper or magazine or other printed matter, in the Maja Taqlid is insulted or false information is spread about him or the Marja Taqlid is directly or indirectly misquoted, the editor and the author are responsible for this act and are punished with imprisonment of between one and three years. This is an official offense that is being prosecuted ex officio. ”By referring to section 17 of the Iranian press law, Baqai clearly wanted to prevent articles from appearing in the press that linked Khomeini with the violent demonstrations of the 15th Chordad bring. In this case, the articles could have been interpreted as an insult to Khomeini, who has meanwhile risen to Marja Taqlid, and the journalists concerned would have been threatened with imprisonment.

The demand for political immunity for Khomeini

On July 27, 1963, Ayatollah Shariatmadari let the news spread that there was a rumor that Khomeini would be deported into exile. The ayatollahs Shariatmadari, Milani and Golpaignai then issued a joint fatwa stating that, according to Article 2 of the amendment to the Iranian constitution, the highest ayatollahs had immunity and could neither be arrested, convicted nor deported into exile. The fact that Article 2 of the amendment to the Iranian constitution does not at all refer to the question of the legal responsibility of an ayatollah was obviously irrelevant to the fatwa. From the provision that, according to Article 2 of the amendment to the Iranian constitution, a committee of clergymen must review every law of parliament for its conformity with Islam, they deduced that the clergy were above the legislature and thus also above the law. After this perversion of the law , they initiated a campaign aimed at convincing the population that the highest clergy could neither be accused nor punished and certainly not executed. The success of this campaign was not long in coming, as the population soon believed that the Iranian constitution would forbid the sentencing and execution of ayatollah to death.

Khomeini is released from prison and placed under house arrest

After Khomeini was confirmed in his new position by a fatwa, General Hassan Pakravan took action. After consulting with Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, he went to Eshratabad on August 2, 1963 to visit Khomeini in the military prison and to inform him that he would be transferred to a villa in Dawudieh, a district of Tehran, on the same day. The following day, an article appeared in the Tehran daily press which, based on information from the SAVAK, spoke of an agreement with Khomeini in which he undertook not to interfere in political matters or to violate law and order. For this reason, Khomeini was released from custody. However, he is under house arrest in Tehran.

After Khomeini was released from house arrest, the trials of the 18 people still in custody began on August 2, 1963. The process began with the preparations for the elections to the 21st parliament. The ayatollahs Shariatmadari, Choi, Milani, Marashi, Najafi declared that a strike would begin at 12 noon on October 5, 1963 until the arrested persons were finally released. However, the elections went without incident, so that Parliament was able to meet for its constituent session on October 6, 1963. The following day, as a gesture of goodwill, the government released all ayatollahs still under house arrest. Only Khomeini remained under house arrest. Ayatollah Schariatmadari had meanwhile returned to Qom and had resumed teaching at his religious school. He opened the course with a speech in which he warned that Khomeini was still under observation, that he had legal immunity as Marja and supreme leader and that it was illegal to prosecute him or even to convict him.

“We don't stand up for our personal interests. Rather, we want the laws of Islam to apply in Iran, and that no law is officially passed in Iran that violates Islam. "

The sentences against the other arrested persons

The trials of the other arrested persons ended on November 2, 1963 with death sentences for Teyyeb Haj Rezaie and his brother Haj Ismael Rezaie . All the rest, including Mehdi Bazargan and Ayatollah Mahmud Taleghani , received prison terms.

In the months that followed, the clergy continued to demand Khomeini's release. Three of the most active followers of Khomeini, the mullahs Ahmad Khosroshahi , Mohammad Ali Razi Tabatbai and Mehdi Darwazei , were arrested on December 3, 1963 and taken to Tehran. Several notable clergymen issued a statement against the arrests.

Prime Minister Alam resigns

The political situation remained tense until Asadollah Alam resigned on March 7, 1964. The political pressure that began with the events of June 5, 1963, had not eased due to the ongoing protests against the reform program and demands for Khomeini's release.

With Alam's resignation and the assumption of office of the new Prime Minister Hassan Ali Mansour, there was hope that a new political beginning would bring about reconciliation with the clergy. On March 8, 1964, the leading clergymen sent a telegram to Prime Minister Mansour demanding freedom for Khomeini and the repeal of all laws directed against Islam.

Khomeini is set free

April 5, 1964 was to bring about the turning point. Prime Minister Mansour announced in a speech that peace would be made with the clergy:

“We believe that the Iranian nation and the Iranian government are a unit, that my government is an Islamic government, and that Islam is one of the most modern and best religions in the world. We respect the clergy and I have received the mandate from the Shah to convey his friendly greetings to the clergy. "

The following day, Khomeini was released from house arrest and brought back to his house in Qom with a police escort.

Interior Minister Javad Sadr visited Khomeini and informed him that he was free from the point of view of Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi and the government of Prime Minister Mansour.

Further development

The peace shouldn't last long. On October 26, 1964, Khomeini warned in a speech to members of the army, members of parliament, the merchants of the bazaar and colleagues of the clergy that this government was dreaming of destroying Iran. He urged the leaders of all Islamic countries to come to the aid of the Muslims of Iran:

“... America is the source of our problems. Israel is the source of our problems. And Israel is America. These ministers are all from America. All are American lackeys. If it weren't for you, why don't you get up and protest loudly. The laws of this Parliament are illegal. The entire parliament is illegal. Article 2 of the Amendment to the Iranian Constitution, according to which a group of five mullahs must agree to any law after reviewing it to ensure that it complies with Islam, was ignored. ... I pray to God that he will destroy all those who betrayed this country, Islam and the Koran. "

After this speech, Khomeini was arrested on November 4, 1964 on orders from Mansour and flown in a military plane into exile in Turkey to Bursa . He was forbidden from any political activity there. Furthermore, he was not allowed to wear his turban and the aba'a , the traditional garb of a Shiite clergyman.

Prime Minister Hassan Ali Mansour's decision to deport Khomeini should cost his life. On January 22, 1965, a few days before the first anniversary of the White Revolution, Mansour's car stopped in front of the Parliament building at around 10 a.m. Mansour wanted to deliver his first State of the Union address to Parliament. He got out of his car. Mohammad Bokharaii, a member of Fedayeen -e Islam , stepped up to Mansour from the crowd of waiting spectators and shot three times. Mansour was put back in the car and driven to the hospital, where he died five days later.

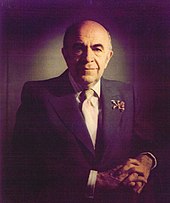

On the same day, Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi appointed Mansour's close confidante Amir Abbas Hoveyda, pending his confirmation by parliament, as acting prime minister, in order to make it clear that he wanted to implement the reforms of the White Revolution under all circumstances and neither from Khomeini would be dissuaded by the rest of the clergy or the political opposition. Hoveyda, who carried on the reform program initiated by Prime Ministers Amini, Alam and Mansour, was to remain Prime Minister for the next 13 years until August 5, 1977.

Before Khomeini returned on February 1, 1979, Hoveyda was arrested. Friends tried to persuade Hoveyda to flee because the prison guards had fled the revolutionaries of the Islamic Revolution and Hoveyda was free to leave. But Hoveyda stayed. He had nothing to reproach himself for and believed that he could stand up to any court. Although he would have been entitled to a luxurious service villa as prime minister, he had lived very modestly with his mother in a small house in Darus, a district of Tehran, and had been given a dark blue pecan all these years, with the same furnishings as he was for sold to the common man, drove to the Prime Minister's office. His driver usually sat in the back because he liked to be at the steering wheel himself. Hoveyada was a man of the people and therefore felt safe.

Mehdi Bazargan, the former political opponent of Hoveyda, had become Prime Minister on February 5, 1979. The followers of Khomeini took Hoveyda to the Refah school , Khomeini's headquarters. Then, on March 15, 1979, the first trial took place, which was to last only two hours. The court, headed by Revolutionary Judge Sadegh Khalkali , did not come to a verdict after two hours and adjourned. Another hearing took place on April 7, 1979. This time the verdict was reached after two hours. Hoveyda has been charged with seventeen offenses, including "destruction of agriculture and forests". Just minutes after Khalkali read the death sentence, he was taken into the school yard and shot twice. Severely wounded, he asked that he should finally be shot. Khalkali is said to have fired the last and fatal shot himself. Others say that a clergyman named Ghaffari killed Hoveyda. Hoveyda's corpse remained a showpiece of the Revolution in the forensic medicine cold room for three months until it was finally buried anonymously in an unknown location. Prime Minister Mehdi Bazargan resigned on November 5, 1979 following the hostage-taking of Tehran , who believed that radical organizations would undermine his government.

Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, who left Iran on January 16, 1979, died after an odyssey through Egypt, Morocco, the Bahamas, Mexico, New York and Panama on July 27, 1980 in the Cairo military hospital Maad of complications from cancer.

Remembrance day

June 5, 1963 (15th Khordad 1342) was seen by Khomeini and his followers as the beginning of the Islamic Revolution . With the establishment of an Islamic Republic in Iran, the 15th Chordad became a day of remembrance. It is recalled that the events of the 15th Khordad in 1342 gave rise to a political movement in Iran which, after 16 years of opposition, led in January 1979 to the overthrow of Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi and the establishment of an Islamic republic by Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. In the preamble to the Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Iran, a whole paragraph is devoted to the importance of this day:

"Imam Khomeini's devastating protest against the American conspiracy known as the White Revolution ..."

In addition, a station on the Tehran subway was named after the 15th Chordad.

literature

- Iraj Pezeshkzad: 15 Khordad. Los Angeles 2008, ISBN 1-59584-168-7 .

- Mehdi Shamshiri: Gofteh Nashodeh-hayi dar bareyeh Ruhollah Chomeini ( Untold storys about Rouhollah Khomeini ). 2013, ISBN 978-0-578-08821-1 .

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Gholam Reza Afkhami: The life and the times of the Shah. The University of California Press, 2009, p. 227.

- ↑ Gahnameh, 3: 1279, 1290.

- ↑ Gholam Reza Afkhami: The life and the times of the Shah. The University of California Press, 2009, p. 230.

- ↑ Ruzshomar, 2: p. 148 f.

- ↑ Ruzshomar, 2: p. 150.

- ↑ Gahnameh, 3: p 1305 f.

- ↑ Gahnameh, 3: S. 1310th

- ↑ Ruzshomar, 2, p. 153.

- ↑ Iraj Pezeshkzad: 15 Chordad. Los Angeles 2008, p. 25 f.

- ↑ Gahnameh, 3: S. 1316, 1324, 1328th

- ↑ Gholam Reza Afkhami: The life and times of the Shah. University of California Press. 2009, p. 234.

- ↑ Iraj Pezeshkzad: 15 Chordad. Los Angeles 2008, p.

- ↑ Olmo Gölz: Representation of the Hero Tayyeb Hajj Reza ʾ i: Sociological Reflections on javanmardi . In: Lloyd Ridgeon (Ed.): Javanmardi: The Ethics and Practice of Persianate Perfection . Ginkgo Press, Berkeley, CA 2018 ( academia.edu ).

- ↑ Mehdi Shamshiri: Gofteh Nashodeh-hayi dar bareyeh Ruhollah Chomeini ( what was not said about Ruholla Chomeini ), Pars Publication, Huston Texas 2002, p. 108 f.

- ↑ Iraj Pezeshkzad: 15 Chordad. Los Angeles 2008, p. 74.

- ↑ Iraj Pezeshkzad: 15 Chordad. Los Angeles 2008, p. 75.

- ↑ Shojaedin Shafa: Genayat va Mokafaat ( murderer and punishment ). Paris, p. 1365.

- ↑ Abbas Milani: Eminent Persians. Volume 1. New York, 2008, p. 112.

- ^ Defeat of the first plot against Ayatollah Osma Khomeini and the Islamic movement of the Iranian people. Workers' Party of the Iranian People, Hesbe Zachmatkeshan Mellat-e Iran, 1963, p. 30.

- ^ Defeat of the first plot against Ayatollah Osma Khomeini and the Islamic movement of the Iranian people. Workers' Party of the Iranian People, Hesbe Zachmatkeshan Mellat-e Iran, 1963, p. 14 f.

- ^ Defeat of the first plot against Ayatollah Osma Khomeini and the Islamic movement of the Iranian people. Workers' Party of the Iranian People, Hesbe Zachmatkeshan Mellat-e Iran, 1963, pp. 36–40.

- ↑ Mehdi Shamshiri: Gofteh Nashodeh-hayi dar bareyeh Ruhollah Chomeini ( What has not been said about Ruholla Chomeini ), Pars Publication, Huston Texas, 2002, p. 110 f.

- ↑ Iraj Pezeshkzad: 15 Chordad. Los Angeles, 2008, p. 78

- ↑ Iraj Pezeshkzad: 15 Chordad. Los Angeles 2008, p. 80 f.

- ↑ Iraj Pezeshkzad: 15 Chordad. Los Angeles 2008, p. 81.

- ↑ Iraj Pezeshkzad: 15 Chordad. Los Angeles 2008, p. 82.

- ↑ Ruz Shomar-e Tarikh Iran. Vol. 2, p. 156.

- ↑ Ruzshomar, 2: p. 465 ff.

- ↑ Abbas Milani: Eminent Persians. Syracuse University Press, 2008, p. 204.

- ↑ servat.unibe.ch Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Iran (accessed on March 29, 2014)