Battle of the Barents Sea

| date | December 31, 1942 |

|---|---|

| place | Barents Sea |

| output | British victory |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

| Commander | |

| Troop strength | |

| 1 ironclad , 1 heavy cruiser , 6 destroyers |

2 light cruisers , 5 destroyers, 5 smaller ships |

| losses | |

|

330 dead, |

250 dead, |

The Battle of the Barents Sea , also known as Operation Rainbow in German naval history , was a skirmish between British and German naval forces during World War II . The battle took place on December 31, 1942 in the sea area in front of the North Cape and ended with a withdrawal of German forces. A few days later, the outcome of the battle indirectly led to the resignation of Grand Admiral Erich Raeder and to the final cessation of construction work on heavy warships in Germany.

background

After the German attack on the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941, the British began to deliver war material to their Soviet allies in the autumn of the same year by means of convoy trains. The convoys gathered in British ports such as Liverpool or Loch Ewe and also in Iceland , which had been occupied by British troops in May 1940 in response to the German occupation of Denmark and Norway . The route ran through the North Sea , around the North Cape and ended in Murmansk or Arkhangelsk . The distance to the Norwegian coast, and thus to the German naval and air force bases, was determined by the pack ice border . In winter there was no more than a navigable corridor of 200 to 250 nautical miles between the North Cape and the ice.

Convoy war in the North Sea

After the German troops were stopped in front of Moscow in December 1941 and the targeted blitzkrieg against the Soviet Union had thus failed, the strategic importance of the Arctic convoys for the high command of the Wehrmacht became increasingly important. Therefore, at the end of the year, the first submarines were relocated to the North Sea. Hitler told the commander of the submarines that he would rather

- if 4 ships carrying tanks to the Russian front were sunk, than 100,000 GRT in the South Atlantic.

After the loss of the Bismarck in May and the repeated damage to the other heavy ships that were exposed to Allied air raids in French ports , the idea of using surface forces in the Atlantic was abandoned and the remaining ships were first ordered back to Germany ( Cerberus company ). The operational ships and a number of submarines were relocated to Norway since the beginning of 1942, on the one hand to ward off a feared Allied invasion, on the other hand to combat the convoys under favorable circumstances.

Several advances by the heavy German surface forces remained unsuccessful, as they either did not find their opponent due to bad weather or poor visibility or avoided British cruisers and battleships due to orders not to take too high a risk. Only the Rösselsprung company , the attack on convoy PQ 17 in July, indirectly led to success. When the British Admiralty became aware of the departure of the Tirpitz , Admiral Scheer and Admiral Hipper , they ordered the escorts to withdraw and the convoy to disband. For the most part, the merchant ships, which now operated individually, were sunk by submarines and aircraft.

Convoy JW 51

After the convoy PQ 18 had suffered heavy losses in September, the next one, named JW-51, was split into two groups that set sail from Loch Ewe on December 15 and 22, 1942. In addition to the immediate escort of destroyers and smaller units, they received a close coverage group of two cruisers and long-range coverage by the battleship HMS Anson and a heavy cruiser. The first group, JW-51A, reached Kola Bay without incident on December 25th. The second group, JW-51B, consisting of 14 merchant ships , was discovered and reported by German aerial reconnaissance and a submarine on December 30th near Bear Island . Then the “Rainbow Company” began. Vice-Admiral Oskar Kummetz went to sea on the same day with the heavy cruisers Lützow and Admiral Hipper and six destroyers. The aim was to destroy the evidently poorly secured convoy. The German reconnaissance had missed the long-range cover group, and the two cruisers were at times far away from the convoy to bunker fuel in the Kola Fjord. Nevertheless, Kummetz also operated under the instruction not to take unnecessary risks. In particular, this meant avoiding battles, even with opponents of equal strength, avoiding night battles and in particular damaging the Lützow , and not spending any time on rescuing castaways.

Ships involved

Allied forces

| Commander | Ships | Armament (per ship) |

|---|---|---|

| RL Burnett | Light cruiser HMS Sheffield , HMS Jamaica | 12 x 15.2 cm; 6 torpedo tubes |

| R. Sherbrooke | Destroyers HMS Achates , destroyers HMS Onslow , HMS Obdurate , HMS Obedient and HMS Orwell ; 1 minesweeper , 2 corvettes , 2 armed trawlers |

4 × 12 cm; 8 torpedo tubes 4 x 10.2 cm; 8 torpedo tubes 1 × 10.5 cm |

The long-range cover group with the battleship HMS Anson and the heavy cruiser HMS Cumberland were too far away to be able to intervene in the fighting.

German armed forces

| Commander | Ships | Armament (per ship) |

|---|---|---|

| O. Kummetz |

Heavy cruiser Lützow , heavy cruiser Admiral Hipper ; Destroyer Z 4 Richard Beitzen , Z 16 Friedrich Eckoldt , Z 6 Theodor Riedel , Z 29 , Z 30 , Z 31 |

6 × 28 cm; 8 × 15 cm; 8 torpedo tubes 8 × 20.3 cm; 12 x 10.5 cm; 12 torpedo tubes 5 x 12.7 cm; 8 torpedo tubes 5 × 15 cm; 8 torpedo tubes |

- ↑ Heavy anti-aircraft guns .

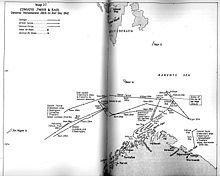

Course of the battle

Combat contact

The attack was supposed to take place on New Year's Eve during the morning hours, because during the polar night there was only at least a slight twilight that allowed visibility of up to ten nautical miles. However, there were also banks of fog and snow showers, which in some cases severely restricted the visibility. Kummetz had divided his ships into two groups - one cruiser and three destroyers each. The Admiral Hipper was supposed to overtake the convoy from aft, attack and secure the convoy, while the Lützow and her destroyers were to approach from the south and attack the convoy directly. The two British cruisers were still a good way to the north, as Burnett had difficulties in the prevailing conditions to find the convoy again. At 8:20 am, the corvette HMS Hyderabad first sighted the destroyers from the northern group led by Admiral Hipper , but did not report this. Shortly afterwards, Kummetz's ships were also discovered by the destroyer HMS Obdurate , which was approaching them at increased speed for identification. When the Obdurate approached the German ships within four nautical miles, they opened fire. The Obdurate initially turned off, was not followed and reported contact with the enemy.

Firefights

The four British destroyers HMS Onslow , HMS Obdurate , HMS Obedient and HMS Orwell formed to attack the German unit, while the destroyer HMS Achates and the other escort ships stayed with the freighters and tried to put a smoke curtain around the convoy. At around 9.45 a.m., the Admiral Hipper opened fire on HMS Achates from the north , which HMS Onslow and HMS Orwell then rushed to help. The Onslow received heavy hits, as a result of which several crew members were killed or wounded, including the commander of the escort service, Captain Robert Sherbrooke . At the same time, the mine sweeper HMS Bramble was sunk by the Admiral Hipper , with 121 people killed on this ship alone.

The cruisers HMS Sheffield and HMS Jamaica were meanwhile running at full speed towards the battlefield after receiving enemy reports and sighting the muzzle flash. Burnett did not receive a clear picture of the situation, however, and the Admiral Hipper disappeared temporarily in the snowstorm. Instead , the southern group led by the Lützow appeared south of the convoy (around 10:45 a.m.) - also first sighted by the Hyderabad , which, however, did not pass on this enemy report. Only when Sherbrooke's destroyers discovered the Lützow at 11:00 a.m. , measures were taken: The four O-class destroyers lay down between the Lützow , whose commander had not yet attacked, and the convoy. That in turn gave Admiral Hipper the opportunity to resume their attack. The cruiser scored hits on the Achates and the Obedient . The Admiral Hipper itself, however, formed a clear target in front of the dodgy horizon for the British cruisers HMS Sheffield and HMS Jamaica , which had arrived in the meantime and were able to score hits with their first salvos, reducing the speed of the Admiral Hipper to 28 knots. Kummetz decided, as ordered, to break away from this enemy in a westerly direction. One of his companion destroyers, the Z 16 Friedrich Eckoldt , mistook the Sheffield for the Admiral Hipper and took a position near the British cruiser, whereupon the destroyer with the entire crew was sunk by the Sheffield within a few minutes .

At around the same time - around 11:45 a.m. - the Lützow opened fire. It damaged a merchant ship before Sherbrooke's destroyers managed to put a wall of smoke in front of the fleeing convoy. Around 12:30 p.m. there was another exchange of fire between the Admiral Hipper and the British cruisers, but without a hit. Kummetz finally withdrew with all ships in a westerly direction, and in the afternoon Burnett's cruiser lost contact with the German association. The badly damaged HMS Achates sank at 1:15 p.m., 113 men were killed.

aftermath

The losses were comparable despite the German superiority (two heavies against two light cruisers): The German Navy lost a destroyer, the Royal Navy a destroyer and a mine sweeper. Other destroyers were damaged as well as the Admiral Hipper on the German side . There were several hundred dead on both sides. The victory lay mainly in strategic terms with the British: The convoy JW-51B reached the Soviet ports without further losses. The commander of the Home Fleet , Admiral John Tovey , emphasized as a special achievement that the five destroyers Sherbrookes had managed to keep the superior German forces away from the merchant ships over a period of four hours. Sherbrooke received the Victoria Cross for this .

Raeder's farewell

However, the far more significant consequences of the battle were in Germany. According to testimony from several witnesses at the Fuehrer's headquarters , Hitler was furious when he learned of the outcome of the battle. Apparently he got the news on the British radio even before Raeder, as Commander in Chief of the Navy, had officially made a report. Hitler, who by this time had already complained about the "uselessness" of the heavy warships, asked Raeder to visit him on January 6, 1943. In the presence of Keitel, he asked Raeder to shut down all large naval units in order to free up personnel capacities for other parts of the armed forces and the armaments industry. Raeder, who saw his life's work failed, then submitted his resignation.

His successor was on January 30, 1943, the commander of the submarines , Karl Dönitz , who actually presented a detailed plan for the decommissioning of the heavy warships just a week after taking office and also had all work on new buildings suspended ( aircraft carrier Graf Zeppelin ). Even if Dönitz later refrained from rigorous decommissioning, the battle in the Barents Sea had far-reaching consequences for the German naval armament, because with the replacement of Raeder by Dönitz, he was now able to direct all of his efforts to the mass production of submarines, which he already did had been demanding since 1939. In 1943, the German submarine weapon was able to use significantly more boats in the battle of the Atlantic than before.

literature

- Michael Salewski : The German Naval Warfare 1935-1945 . 3 volumes, Frankfurt a. M. 1970-1975, ISBN 3763751688 .

- Elmar B. Potter, Chester W. Nimitz, Jürgen Rohwer: Seemacht. A naval war history from the beginning to the present . Herrsching 1982, ISBN 3881990828 .

- Geoffrey Bennett: Naval Battles in World War II . Augsburg 1989, ISBN 3893500650 .

Web links

- Jürgen Rohwer , Gerhard Hümmelchen : Chronicle of the naval war 1939-1945

- HJ Scott-Douglas: The Last Commission of HMS Achates. In: WW2 People's War. BBC, archived from the original on November 3, 2012 ; Retrieved July 1, 2018 (report by a survivor of the agates ).

- Company rainbow. In: German naval history. Archived from the original on September 27, 2004 ; accessed on July 1, 2018 .