Four Land Tournaments

As a four-country tournaments a short-lived wave were of tournaments called, held from 1479 to 1487 in southwestern Germany. The "Vier-Lande" referred to the tournament landscapes of Franconia , Swabia , on the Rhine River ( Middle and Lower Rhine ) and Bavaria . The tournaments were:

- Würzburg (January 10-12, 1479)

- Mainz (August 1480)

- Heidelberg (August 26-28, 1481)

- Stuttgart (from January 7, 1484)

- Ingolstadt (September 5-8, 1484)

- Ansbach (May 16-18, 1485)

- Bamberg (January 8-10, 1486)

- Regensburg (February 4th - 7th, 1487)

- Worms (August 26-28, 1487)

These nine tournaments stand out from the multitude of other regional, cooperative, organized as a group fighting tournaments and courtly festivities, or single jump ( joust ) out because they are extremely well documented, were purely organized cooperative while but - nationwide - united the four tournament landscapes. That they were also subject to - increasingly refined - regulations and that there were no similarly designed tournaments outside of this region, either before or after this time.

The family chronicle of Michael von Ehenheim , the records of Siegmund von Gebsattel , a Würzburg knight then residing in Röttingen an der Tauber, and Ludwig von Eyb, the younger , and Ludwig von Eptingen from Basel are available as contemporary reports .

The four-country tournaments as the culmination of a unique tournament tradition

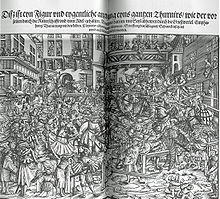

The regulations and special admission restrictions were included in a large number of tournament and coat of arms books. For example, the Ingeram Codex (around 1459) are partially sorted according to aristocratic tournaments . Likewise the book of arms of Conrad Grünenberg (1483). Detailed descriptions of the individual tournaments followed, such as the Würzburg tournament book about the tournament from 1479 and the tournament chronicle of Jörg Rugen from 1494. This has meanwhile been equated with Georg Rüxner . Its tournament book from the beginning of 1530 , originating from and originating from the tournament in Teutscher Nation, shaped the picture of these tournaments through countless copies and reprints. Rüxner last recorded 36 official tournaments between 939 and 1487. This list is only considered reliable from the 15th century. This last work in particular makes clear the role that these tournaments played in the noble self-image of the time. Initially, the aristocrat stood out from his peers, and especially from possible upstart, simply by participating in the tournaments. Participation in each individual tournament was preceded by an elaborate coat of arms show, in which the nobleman had to prove that his ancestors had already participated in such tournaments. The tournament books now served to document such an origin. With the listing of participants in older tournaments, tradition was also constructed.

The most important demarcation element of these tournaments was that they were organized by the, mostly non-rural, lower nobility themselves. Here a courtly way of life could be practiced without direct dependence on the princes and the nobility could set themselves apart from rich citizens. But this was only possible with certain restrictions. For organizational reasons, these events could only be held in the cities and, with the exception of Regensburg and Worms, the approval of the prince in whose royal seat the tournament was held was always necessary .

There were co-operative tournaments even before this series, but the tournament of 1479 saw itself as a resumption after a long break. Ehenheim reports a 30-year break. On the other hand, between 1410 and 1413 , Philipp von Kronberg was able to take part in a total of 13 tournaments on the Middle and Lower Rhine, in Swabia and in Franconia. These, as well as well-documented tournaments at the time of the Council of Basel in Schaffhausen , were only organized regionally and did not come close to the number of participants in the “four-country tournaments”. In this international reception, which was particularly underlined by the fact that René d'Anjou highlighted this type of tournament as exemplary in his tournament book, Werner Paravicini sees the uniqueness of the cooperative tournaments also on a European level.

The course of the tournaments

The tournaments were major events that were in no way inferior to the royal weddings. Around 780 tournaments and well over 1500 active participants with a train of 4073 horses took part in the first tournament in Würzburg. According to Ludwig von Eptingen, there were 441 helmets in Heidelberg, 90 helmets were rejected. Two tournament rounds had to be carried out. In Stuttgart Eptingen had 320 helmets, in Ansbach 305. The number of participants decreased over time. The Rhinelander were absent from Regensburg. In Worms there were still 223 helmets.

The tournaments always followed the same pattern:

- On the first day there was a helmet show, with the selected women, with the support of the tournament judges, checking the access authorizations.

- On the following day, the participants were divided into two parties, who then fought out the piston tournament. All 200-300 participants fought, like in a battle, between the barriers on the town's market square. A second phase could follow with blunt swords, or single stabbing with the lance. Since the piston tournament was seen as the higher-ranking, befitting event, the differentiation between aristocratic Spangenhelm and bourgeois stech helmet emerged in heraldry .

- In the evening, the “tournament thanks”, the winner's prize for each of the “four countries” was presented. A banquet and a dance followed. The statutes of aristocratic societies often included the obligation to bring at least one female notable person. Anyone who did not comply was obliged to pay fines.

The deliberations at the "four-country tournaments" ultimately resulted in the Heilbronn tournament regulations of 1485. This represented a proper status code. In addition to the fines for violating the dress code, or the aforementioned missing tournament lady, corporal punishment for dishonorable behavior was also given established, for example the "putting on the pole". In the tournament descriptions already mentioned, this punishment was mentioned at several tournaments. The access restrictions to the tournaments were also specified in detail.

Sigmund Gebsattel was initially rejected. He got himself eleven customer letters, which attested his tournament ability through the existence of four tournament ancestors who had participated in tournaments in the last 50 years. To spare his offspring this disgrace, he wrote his tournament descriptions and noted his five tournament participations.

The end of the tournaments

The cooperative tournaments ultimately failed because of their own success. The effort required had become greater and greater and the admission requirements initially became increasingly strict. The independence of the tournament nobility was also less and less given. In Bavaria, the prince himself took the lead in the tournament aristocracy. The Bavarian aristocracy soon featured the Wittelsbach diamonds on their tournament flag. A truly free knighthood could only survive in Swabia and Franconia.

The future belonged to the royal and patrician tournaments. They are particularly attested in Saxony and Bavaria and at the court of Emperor Maximilian I for the first half of the 16th century. Despite changed war techniques, knight games retained their role at princely festivals well into the 17th century, and even into the 18th century in Sweden, even in 1912 under the sign of the “political historicism” of the House of Krupp . The renaissance of such knight tournaments today shows that the fascination with them is still unbroken.

literature

- Christian Meyer: The family chronicle of the knight Michel von Ehenheim (1137-1500). In: Journal for German Cultural History. NF = 3rd series vol. 1, 1891, ZDB -ID 192-2 , pp. 69–96, 123–146 (also special print: Stuber, Würzburg 1891).

- Hans H. Pöschko: Tournaments in central and southern Germany from 1400 to 1550. Catalog of the fighting games and the participants . Stuttgart 1987 ( archive.org - Stuttgart, Univ., Phil. Diss.).

- Werner Paravicini : The knightly and courtly culture of the Middle Ages (= Encyclopedia of German History . Volume 32 ). Oldenbourg Verlag, Munich 1994, ISBN 3-486-53691-5 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Still legendary today: the Landshut wedding .

- ↑ Werner Paravicini: The knightly courtly culture of the Middle Ages . S. 94 .

- ↑ Christian Meyer: The family chronicle of the knight Michel von Ehenheim (1137-1500). New edition: Sven Rabeler: The family book of the knight Michel von Ehenheim (around 1462 / 63–1518) . Kieler Werkstücke E, Vol. 6, Frankfurt am Main 2007, ISBN 978-3-631-56847-7

- ↑ Sigmund von Gebsattel: The records of Siegmund von Gebsattel about the tournaments from 1484–1487. In: Display for the customer of the German prehistory. NF Vol. 1, 1853, ZDB -ID 500020-8 , pp. 67-69.

- ^ Gundolf Keil : Siegmund von Gebsattel, called Rack. In: Author's Lexicon . Volume VIII, Col. 1207 f.

- ↑ Ludwig von Eyb d. J .: The stories and deeds of Wilwolt von Schaumburg (= library of the Litterarian Association in Stuttgart. Vol. 50, ISSN 0340-7888 ). Published by Adelbert von Keller . Literary Association, Stuttgart 1859, digitized .

- ↑ Dorothea A. Christ: The family book of the Lords of Eptingen (= sources and research on the history and regional studies of the canton of Basel-Landschaft. Vol. 41). Verlag des Kantons Basel-Landschaft, Liesetal 1992, ISBN 3-85673-228-4 (also: Basel, Univ., Diss., 1991).

-

↑ Charlotte Becher, Ortwin Gamber (ed.): The heraldic books of Duke Albrechts VI. from Austria. Ingeram Codex of the former Cotta Library (= year book of the Heraldic-Genealogical Society Adler . 3rd episode, vol. 12). Hermann Böhlaus Nachf., Vienna et al. 1986, ISBN 3-205-05002-9 . ; see also

Commons : Ingeram Codex - collection of pictures, videos and audio files

.

- ^ Berlin Kupferstichkabinett, 77 B 5.

- ^ Georg Rixner: tournament book. = Tournament book 1530 (= library for genealogists 2). Reprint of the superb Simmern 1530 edition, introduced by Willi Wagner. E. & U. Brockhaus, Solingen 1997, ISBN 3-930132-08-7 .

- ↑ At that time, the Bavarian tournament nobility found itself in a situation between asserting independence and being a resident. See also: Böcklerkrieg and Löwlerbund .

- ↑ Sigmund von Gebsattel: The records of Siegmund von Gebsattel about the tournaments from 1484–1487.

- ↑ There is a very detailed report of the tournament in Schaffhausen in 1436 by the Castilian embassy at the Council of Basel. The Traité de la forme et devis comme on fait les tournois , 1451-1452 by René d'Anjou also contains the oldest known depiction of a helmet show. Werner Paravicini: The knightly courtly culture of the Middle Ages . S. 100 f .

- ^ Andreas Ranft : Noble societies . Group formation and cooperatives in the late medieval empire (= Kiel historical studies . Volume 38 ). Thorbecke, Sigmaringen 1994, ISBN 3-7995-5938-8 , p. 146 f . (At the same time: Kiel, University, habilitation thesis, 1994).

- ↑ Werner Paravicini: The knightly courtly culture of the Middle Ages . S. 98 .

- ↑ Werner Paravicini: The knightly courtly culture of the Middle Ages . S. 101 .