Villa of Horace

The Villa of Horace is a Roman country house and an archaeological site in the Sabine Mountains (hence also called Sabinum ) near the present-day city of Licenza in the Italian metropolitan city of Rome . The poet Horace got the house in the 30s of the first century BC. Given by his patron Maecenas . At that time it belonged to the Augustan region IV not far from the Latin city of Tibur . Horace processed it thematically in his poetry and dedicated several smaller works to it.

Since Horace reported frequently and in detail about his Sabinum, its research was not only of importance for archeology and, together with its descriptions, for the social history of the poet, but also served for a better understanding of the Sabinum as a symbol for the poet's philosophical views.

Discovery and Location

Location with Horace

In his odes and epistles , Horace described the location of his country house in detail. The Sabinum lay in a secluded valley between two mountain ranges of the Sabiner Mountains, which ran from north to south in a side valley parallel to a larger connecting road, the Via Valeria . The height of the country house is controversial, as Horace himself described that there was a small grove above it. Since the super in Horace description can be translated as "above" as well as "beyond", a dissent arose as to whether a real grove existed above the Sabinum or whether Horace would have liked such a grove beyond what was described. The house was still at a source of drinking water, which Horace called Bandusia and which possibly provided a tributary of the Digentia brook . There was also a temple of Vacuna, the clear Echohang Ustica and Mount Lucretilis nearby. The description of the climate bears typical traits of a locus amoenus . The house was in the cool shade of the forest and had a comfortable temperature in summer, the winters were mild. However, the climatic description of Horace varies depending on the poem. He knew how to heat the Sabinum, for example. B. often as comfort in the cold of a severe winter, especially when the surrounding area was badly affected by frost. Ernst Schmidt calculated from the information provided by agricultural writers and Horace's information about his slaves and tenants, the total area of a mixed farm to about 321 iugera (approx. 81 hectares ) and classified the property as a medium-sized farm.

Exploration in Modern Times

From the middle of the 16th to the 18th century, German and Italian humanists became increasingly interested in the biography of Horace and the history of his country house, the location and appearance of which they tried to reconstruct based on detailed descriptions of the poet and his vita. The Roman biographer and archivist Suetonius was in the short Vita of the poet to the place to the proximity of the old Latinerstadt Tibur, which meant the lower, southern part of Sabinerlands in the Augustan Regio IV. On the basis of the old street, the Via Valeria , the village of Varia is to be determined more precisely, where the Horatian tenants sold their goods. The Tabula Peutingeriana , a medieval copy of a late antique map of the world from the 4th century, showed the place on the road that was about the eighth milestone before Tibur.

The first modern considerations as to where Horace's country house should be located came from the historian and geographer Flavio Biondo in his Italia Illustrata of 1474, later representations were based on the localization of the geographer Philipp Clüver in his Italia Antiqua (1624). However, the identification of Horazi place names and geographical designations was not very coherent and imprecise for both scholars, so that, according to Clüver, it took another ten years for the geographer Lukas Holste to identify the creek that flows into the Aniene as Digentia in addition to the place Varia . Further determinations of place names followed through measurements, such as Mons Lucretilis as Monte Gennaro . Except for topographical studies, the location of the Sabinum after Holste remained without interest for research for over a century. In 1761 the villa could finally be precisely located, and based on the work of Holste a dispute broke out between the two abbots Domenico de Sanctis and Bertrand Capmartin de Chaupy. With the discovery of the remains of the wall above the Bandusia spring, both discovered the house in the Vigne di St. Pietro parcel , where the ancient foundation walls of the medieval church Ss. Pietro e Marcellino had been put on.

Due to the location in the midst of other villas and businesses and an extensive system of roads that also ran through the valley away from the Via Valeria, it can be assumed that Horace's Sabinum was not as lonely in a secluded location as Dichter would have liked to have described it. Various hypotheses and doubts about the localization of de Sanctis' and de Chaupys, see above. a. that the Bandusia source from a medieval deed of donation to Pope Paschalis II is said to have been near Venusia, Horace's hometown, have not prevailed. Ernst Schmidt argued that the ode in which the source with the poet's poetic reading experience could have been named by himself after a place in his youth.

Archaeological excavations at the Sabinum

Italian archaeologists had been interested in the exact development of the house under the former church since 1911. The archaeologist Angelo Pasqui led the first excavation from 1911 to 1914, which was continued after his death by his colleague Giuseppe Lugli . Lugli and Thomas D. Price began a third excavation in 1930, the results of which they published in Horace's Sabine Farm . Another study by Price appeared in 1932 under the title A Restoration of Horace's Sabine Villa . An excavation from 1997 to 2001 is largely based on Lugli's and Price's descriptions. They reflect the current state of the house as it can be viewed at Vicovaro.

Description of the villa

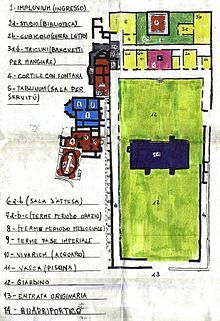

The excavated villa encompasses the foundation walls of a house on an area of 2.75 km², 1.25 km² of which alone are in the garden with a walkway. The floor plan is largely rectangular and slightly axially drawn from northwest to southeast. The garden slopes down to the south. It was designed as a xystus , a planted terrace, and had a large fish pond (piscina) in the middle . The walkway was a cryptoporticus with openings to the inner garden. The shape of the garden did not correspond to that of the usual peristyle villas, which wealthy Romans built in popular places for extensive villa complexes. It was too closed for that. In the higher north part of the house was the residential wing, from which the owner had a view of the mountains of the Licenza valley. The villa had no substructures, although the hill on which it stood (415 m above sea level) has been somewhat straightened out.

In addition to the cryptoporticus, the whole residential wing was separated to the north by another hallway. This resulted in a northern residential area with a large atrium and triclinium , which was adjacent to the corridor to the south, and a smaller residential area with a smaller atrium, which was adjacent to the cryptoporticus. The triclinium in the north living part was divided into two large winter and small summer tricliniums, which were located in the extreme northeast of the house. The smaller triclinium was a passage room. The southern residential part contains the poet's bedroom, which is divided into two parts, on the east side, and several rooms and chambers in the west, possibly intended for the slaves. The residential wing was two-story.

The walls consist of regular opus reticulatum , the floor of opus sectile with simple square shapes. The wall frescoes contain symposiastic scenes, u. a. a naked Bacchus . You are now in the Antiquarium of Licenza.

Horace kept the villa, but not built it or extended it. Due to the accusations that he can be made in Satire 2,3 that he would imitate Maecenas, it is known that he has at least made changes to the house. In the northwest there are thermal baths , which are the best preserved part of the house, but have been heavily rebuilt with the construction of the church since the second century, but at the latest since the eighth century.

literature

- Giuseppe Lugli : La Villa Sabina di Orazio. In: Monumenti antichi, pubblicati per cura della R. Accademia dei Lincei. 32, 1926, pp. 457-598.

- Thomas Price: A Restoration of Horace's Sabine Villa. In: Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome 10, 1932, pp. 135-142.

- Giuseppe Lugli: Horace's Sabine Farm. Rome 1930.

- Robin GM Nisbet , Margaret Hubbard : A commentary on Horace. Odes Book I / II. Oxford 1970/1978.

- Eleanor Winsor Leach: Horace's Sabine Topography in Lyric an Hexameter Verse. In: American Journal of Philology. 114, 1993, pp. 271-302.

- Ernst A. Schmidt : Sabinum. Horace and his estate in the Licenzatal (= Heidelberg Academy of Sciences, writings of the philosophical-historical class. 1997, vol. 1). Heidelberg 1997.

- Bernard D. Frischer, Iain Gordon Brown: Allan Ramsay and the Search for Horace's Villa. Ashgate Publishing, London 2001, ISBN 0-7546-0004-1 review .

Individual evidence

- ^ Camille Jullian : La villa d'Horace et le territoire de Tibur. In: Mélanges d'archéologie et d'histoire. Vol. 3 (1883), No. 3, pp. 83-84.

- ↑ Horace, carmina 1,17,17, cf. epistulae 1,16,5-15.

- ↑ See Horace, saturae 2,6.

- ↑ Cf. Otto Seel : Horazens Sabine luck. Comments on Horace sat. 2, 6. In: Encrypted Present. Stuttgart 1972, pp. 63-75.

- ↑ Horace, epistulae 1,16,5-15, carmina 3,13,6-12.

- ↑ Horace, epistulae 1,17,1-11 and 1,10,49.

- ↑ Horace, Carmina 1, 17, 17-18.

- ↑ Horace, epistulae 1,10,15.

- ↑ Horace, epistulae 1,18,105.

- ^ Ernst A. Schmidt: Sabinum. Horace and his estate in the Licenzatal (= Heidelberg Academy of Sciences, writings of the philosophical-historical class. 1997, vol. 1). Heidelberg 1997, pp. 21-22.

- ↑ See Horace, epistulae 1,14,3.

- ↑ Cf. Nisbet / Hubbard I 1970, for the information given by Horace it is sufficient to verify that the mountain dominated the valley.

- ^ Ernst A. Schmidt: Sabinum. Horace and his estate in the Licenzatal (= Heidelberg Academy of Sciences, writings of the philosophical-historical class. 1997, vol. 1). Heidelberg 1997, p. 32.

- ↑ Lugli, Villa Sabina , p. 503. Cf. Domenico de Sanctis: Dissertazione sopra la villa d'Orazio. Rome 1761 and Bertrand Capmartin de Chaupy : Découvertes de la Maison de Campagne d´Horace. 3 volumes, Rome 1767–1769.

- ↑ See Horace, epistulae 1,14,19.

- ^ Ernst A. Schmidt: Sabinum. Horace and his estate in the Licenzatal (= Heidelberg Academy of Sciences, writings of the philosophical-historical class. 1997, vol. 1). Heidelberg 1997, p. 33.

- ^ Ernst A. Schmidt: Sabinum. Horace and his estate in the Licenzatal (= Heidelberg Academy of Sciences, writings of the philosophical-historical class. 1997, vol. 1). Heidelberg 1997, p. 36 f.

- ↑ Thomas Price: A Restoration of Horace's Sabine Villa. In: Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome 10, 1932, p. 139.

- ↑ Horace, saturae 2 , 3, 307-313.

Coordinates: 42 ° 3 ′ 58 ″ N , 12 ° 54 ′ 4 ″ E