Desert campaign

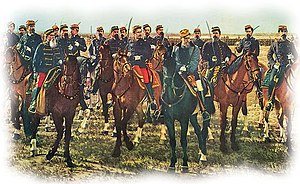

The desert campaign (Spanish both " desert campaign " [" Campaña al Desierto "], " conquest of the desert " [" Conquista del Desierto "] or " desert war " [" Guerra del Desierto "]) was one of General Julio Argentino Roca between 1878 and Military campaign carried out in 1880.

It continued a decade-long series of military actions by the young Argentine nation, in which various indigenous peoples were fought within the framework of border colonization . The campaign aimed to finally secure the Argentine-European dominance over the Pampas and Patagonia . More than 1,000 indigenous people were killed.

background

The formation of the Argentine state began with the May Revolution in 1810 and led to independence in 1816. During the governor of Martín Rodríguez there were clashes with indigenous Patagonians in the border areas to the south and west between 1820 and 1824 , which Juan Manuel de Rosas continued in 1833/34, but not completed. Federico Rauch , of German descent , was involved in the actions. Between 1820 and his death in combat in 1829, he was considered the "horror of the desert".

In the Liberal reign between 1862 and 1880 the fighting came to its final stage. For the upcoming campaigns, Julio A. Roca, in his capacity as minister of war, had a law "extending the borders to the Río Negro " passed in 1878 , which primarily served to borrow from the future beneficiaries so that the campaign could be financed . The aim was to "purify" the territory of inferior populations, although the military had to assume a willingness to exterminate.

The historian Wolfgang Reinhard states that 5.5 million Europeans immigrated between 1870 and 1914, which led to a radical Europeanization of society with an economic boom , and thus a "New Europe" emerged. The land that has been depopulated by Indians has expanded the area under cultivation for wheat and maize by fifteen times, so that the country has become one of the leading exporters of grain. How the pasture economy has increased can be seen from the import of 50,000 tons of barbed wire from the USA between 1877 and 1881 , where it was invented in 1873. At the same time, investments from England in particular resulted in a railway network geared towards the export ports.

At the same time, and with the same motives and backgrounds, there were also actions in the Chaco that were not completed until 1884.

Results

Consequences for the indigenous population

Due to a lack of records, the information on the number of victims on the part of the indigenous population varies. More than 1000 indigenous people were killed in the campaigns. Several thousand people were captured or driven away. In addition, many survivors died of disease and starvation. Some historians speak of genocide.

Consequences for the Argentine economy

Obviously, after the "desert campaign" in connection with the waves of immigration, there was an economic upswing. The result of the campaign is the effective possession of Patagonia by the Argentine nation-state, which was reflected in 1884 with the establishment of the territories (and today's provinces) Neuquén , Río Negro , Chubut and Santa Cruz . The conquered land was used for agriculture and became the cornerstone of Argentina's prosperity at the beginning of the 20th century.

Controversy over Julio Argentino Roca

Today the city of General Roca or the equestrian statue erected at a central location in Buenos Aires reminds us of Roca . Today, however, there is a dispute about whether the price paid for it was necessary for the disenfranchisement and extermination of the Indians. This debate is sparked by the reputation of the “conqueror of the desert” Julio Argentino Roca. The spokesman for the criticism is the historian and human rights activist Osvaldo Bayer , who in numerous statements calls for the removal of all public memories of Roca and for the razing of the equestrian monument in Buenos Aires. The point of departure for this criticism is the willingness to annihilate the Indians and, consequently, the question of whether Roca should be spoken of as someone responsible for genocide . So colloquially those who call the war against the Indians a genocide have turned his middle name “Argentino” into “Asesino” (murderer): Julio Asesino Roca . Roca himself commented on his actions against the Indians in the newspaper La Prensa (Buenos Aires) on March 1, 1878:

“Estamos como nación empeñados en una contienda de razas en que el indígena lleva sobre sí el tremendo anatema de su desaparición, escrito en nombre de la civilización. Destruyamos, pues, moralmente esa raza, aniquilemos sus resortes y organización política, desaparezca su orden de tribus y si es necesario divídase la familia. Esta raza quebrada y dispersa, acabará por abrazar la causa de la civilización. ”

(“ As a nation, we are caught up in a racial dispute in which the native bears the terrible curse of his disappearance written in the name of civilization. So let's destroy good ones Consciously this race, let us destroy its resources and political organization so that its tribal order may disappear and, if necessary, its families dissolved. This bankrupt and dispersed race will eventually join the cause of civilization. ")

Daniel Feierstein , director of the Center for Genocide Studies at the Universidad Nacional de Tres de Febrero (Buenos Aires), assumes that the campaigns against the Indians are a "genocidio constituyente", i.e. genocide linked to the founding of the state. So put Jürgen Osterhammel noted that in the 19th century at the " Frontiers were decimated entire populations" or at least to misery, but new had emerged from the destruction, namely constitutional states.

"Desert" as a metaphor

Since the "desert campaign" was about conquering areas that were to be used economically, the question arises what "desert" should mean here. There is now consensus in Argentine research that “desert” must be viewed as a key word in the ideological discourse of conquest. It is not about something peculiar to the Argentines, but about a commonplace of European colonial thinking, which differentiated between “ civilization ” and “ barbarism ” and the civilized Europeans in the role of “bringers of culture” to the “barbarians” who inhabit the “desert” saw indigenous peoples (cf. Domingo Faustino Sarmiento ). For example, Domenico Losurdo quotes Alexis de Tocqueville in his analysis of the colonial events with a statement from his famous work “ On Democracy in America ” (1835/1840):

“Although the vast land was inhabited by numerous indigenous tribes, it is fair to say that at the time of its discovery it was nothing but a desert. The Indians lived there, but they did not own it, because humans only acquire the land with agriculture and the indigenous people of North America lived on the hunting products. Their relentless prejudices, their indomitable passions, their vices, and even more perhaps their savage strength handed them over to inevitable destruction. The ruin of this population began the day the Europeans landed on their coasts, it went tirelessly and is now almost complete. "

See also

Individual evidence

- ↑ Michael Riekenberg : Little History of Argentina, CH Beck: Munich 2009, ISBN 978-3-406-58516-6 , p. 104 f.

- ↑ a b c The Guardian: Argentinian founding father recast as genocidal murderer. January 13, 2011, accessed November 23, 2018 .

- ↑ Germans on the Río de la Plata

- ↑ The Role of the Argentine Liberals (Spanish)

- ↑ Expansion Act 1878 (Spanish)

- ↑ Michael Riekenberg: Little History of Argentina , CH Beck: Munich 2009, p. 104. - Cf. also Domenico Losurdo: The West and the Barbarians. In: Freedom as a privilege. A counter-history of liberalism , Papyrossa: Cologne 2010, ISBN 978-3-89438-431-9 , pp. 281-307.

- ↑ Wolfgang Reinhard : Brief history of colonialism (= Kröner's pocket edition . Volume 475). Kröner, Stuttgart 1996, ISBN 3-520-47501-4 , pp. 136-138.

- ↑ Felipe Pigna: La Conquista del desierto. Retrieved November 23, 2018 (Spanish).

- ^ Ward Churchill: A little matter of Genocide: Holocaust and Denial in the Americas 1492 to the Present . City Light Books, 1997.

- ↑ Project of a law to topple the Roca monument (PDF file; 520 kB)

- ↑ JA Roca in the twilight (Spanish)

- ↑ Quoted in Der Wüstenkrieg, p. 688. (Spanish)

- ↑ Portrait of Feierstein

- ↑ Constituent Genocide ( Memento of the original from September 20, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (Spanish)

- ↑ Jürgen Osterhammel, The Metamorphosis of the World. A history of the 19th century , 4th, updated edition, CH Beck, Munich 2009; ISBN 3-40658-283-4 , p. 531 f.

- ↑ Ideology of the "desert" (Spanish)

- ↑ Domingo Faustino Sarmiento: “Barbarism and Civilization” review

- ↑ Domenico Losurdo: Struggle for History. Historical revisionism and its myths - Nolte, Furet and the others , Papyrossa: Cologne 2007, ISBN 978-3-89438-365-7 , pp. 236 f.– Losurdo emphasizes that during National Socialism and its colonization projects in Eastern Europe the the same ideas were applied to Jews and Slavs.

literature

- Christine Papp: The Tehuelche. An ethnohistorical contribution to a centuries-long non-encounter , dissertation, Vienna 2002. Online (PDF file; 4.23 MB)