Indigenous people in Argentina

Argentina was inhabited by a large number of indigenous peoples until the arrival of the Spanish in the 16th century . Due to the dominance of European culture in this country, their descendants have only been able to preserve their customs and languages to a relatively small extent. This is where the Indian peoples of Argentina differ from those of many neighboring countries.

Number, definition and names

Estimates of how many Argentines can be called Indians vary widely. The official number, recorded in the 2010 census, is 955,032 people, more than double the value of 403,125 determined in a 2004 special census. Some estimates by non-governmental organizations put it up to two million. The main reason for these discrepancies is the problem of defining the group “Indians”. The census counts are those who identify themselves as Indians or direct descendants of Indians, while other estimates include ancestry or cultural characteristics. According to the 2001 census, 2.8% of all households in Argentina said at least one of its residents was a member of an indigenous culture.

Another definition of the term "Indian" is genetic. According to a study by the University of Buenos Aires in 1992, more than half of all Argentines (56%) have at least one Indian ancestor, and 10% have both parents of Indian descent.

As mestizos ( mestizos ) - mixed race between Indians and Europeans - those people are referred to in official Argentine usage who on the one hand have both Indian and European ancestors and on the other hand identify with parts of the Indian culture (language, religion, customs). According to various estimates, this is around 5 - 10% of the total population (there are no precise data on this). Another definition, which is more widespread among the population, takes as a measure of the term mestizo the presence of physical characteristics that distinguish these people from Argentines of European descent (especially a significantly darker skin color). Large sections of the population use the racist term negro ( Spanish for “negro” or “black”) to refer to these people in everyday language - mostly disparagingly .

ethnicities

The indigenous peoples of South America and thus Argentina were previously divided into three groups according to the now outdated race theories : the "Andids", the "Amazonids" (from the northeast of the subcontinent) and the "Pampids" (also "Patagonids") to which the pampa peoples were also counted. Today, the classification is usually made according to linguistic or ethnic ethnic relationships.

Historical distribution

The geographical spread of the peoples on the territory of Argentina varied greatly, several groups went through sometimes long migrations in the course of their existence as an ethnic group. In the classification presented here, the distribution at the time of the arrival of the Spaniards ( 16th century ) is considered, as the most reliable sources exist.

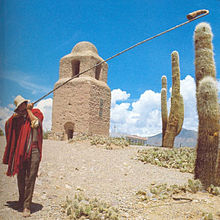

The Kollas , Atacamas and Omahuacas , who were dependent on the Incas for a long time and belonged partly to the Quechua and partly to the Aymara language family, lived in the Andes and the Puna of northwest Argentina . They were the most culturally and architecturally advanced civilization in the region and engaged in agriculture and cattle breeding (especially llamas ). The Diaguita-Calchaquíes in the central northwest had a technology and way of life similar to the Incas, but they resisted them for a long time and were only subjugated by the Spanish. Testimony is the fortifications of Quilmes .

The Huarpes or Huárpidos, who settled in the west and center of Argentina, were also sedentary and engaged in agriculture and cattle breeding. They probably also included the Comechingones in what is now the provinces of Cordoba and San Luis , although this is controversial. Both ethnic groups were not subjugated by the Incas, but only by the Spaniards. They often came into conflict with the also sedentary Sanavirones , who came from the Amazon region in the course of time in the southern Chaco and thus in the border area to the Comechingones.

Ethnic groups of the Guaraní people from the Amazon region settled throughout northern Argentina . These were sedentary hunters and gatherers and also practiced simple tropical agriculture. Some Guaraní groups, now known as Chiriguanos (actually a derogatory term used by the Spaniards), advanced into the Andean region ( Jujuy and Salta provinces ) and adopted the technology of the peoples living there.

The Guaycurú , who migrated from their original homeland of southern Patagonia to northeast Argentina between the 14th and 16th centuries, were the main competitors of the Guaraní in this area, their way of life was similar to that of them. Its main sub-ethnicities are Toba and Mocovíes . The Mataco-Mataguayo family , whose most important representatives are the Wichí (also called Matacos) , also settled in the same region . They were similar to the Guaraní hunters and gatherers who also practiced tropical agriculture.

In the Pampa region and southern Mesopotamia, nomadic hunter peoples who were unfamiliar with agriculture settled. The Charrúas settled east of the Río Paraná ( Entre Ríos and Corrientes ), their area extended into present-day Uruguay . The Het (also Pampas or Querandíes) inhabited the Pampa plain west of the Río Paraná, they were the first to live in the region around Buenos Aires and Rosario , in the vicinity of which the first Spanish fortress in Argentina, Sancti Spiritu , was built in Conflict with the Spanish got. Little is known about the culture of the pampa peoples , as they were acculturated by the Tehuelches and later the Mapuche prior to the conquest by the official Argentine troops .

Two very different peoples settled in Patagonia, the Tehuelche and the Mapuche. The Tehuelche , related to the pampa peoples, inhabited the entire east of Patagonia. They were hunters and gatherers and were partly ousted by the Mapuche culture in the 18th century. The Onas (also Selk'Nam) in Tierra del Fuego also belonged to them . The Yámanas or Yaganes in the south of Tierra del Fuego, on the other hand, were a fishing people who shuttled back and forth between the islands of the South Atlantic (Tierra del Fuego, Isla de los Estados , Cape Horn ).

A special case among the indigenous peoples of Argentina are the Mapuche or Araucans, whose origin is unclear; they could come from the pampas, the central Andean region or the Amazon region. During the 15th, 16th and 17th centuries, when the Spaniards ruled large parts of South America, they migrated from central Chile to the southern Andes region, where they operated south of the Bío-Bío river for a long time parallel to the Spanish and later the new nation Chile is the only entity in South America that can be called an Indian state , even if it was never recognized by the colonial powers. The Mapuche - meanwhile the most powerful of the indigenous equestrian cultures in South America - themselves crossed the Andes in the 17th and 18th centuries in an easterly direction to about the border of the Andean region (e.g. to today's Neuquén province and the southwest of Río Negro ). By the middle of the 19th century, their cultural area spread across practically the entire territory not yet conquered by the Spaniards or the new state of Argentina, the area south of a line between Mendoza and Buenos Aires , with the exception of southern Santa Cruz and Tierra del Fuego . This phenomenon, the so-called Araucanization , is the reason why the Mapuche are today - at least culturally - the largest Indian ethnic group in Argentina. The reason for the Araucanization was probably the high prestige of their language, the Mapudungun , which is described as very varied. Furthermore, numerous epidemics imported by the Spaniards broke out among the pampa peoples in the 18th century, which weakened the resistance of these groups to Araucanization.

Today's distribution

In Argentina today 22 groups are recognized as Indian ethnic groups; The Guaraní (according to the INDEC statistics office ) consider four sub-groups as independent peoples, so that the total number of Indian peoples increases to 25. They are distributed over the territory in the following way:

| Ethnicity | Distribution (provinces) | number | Ethnic group |

|---|---|---|---|

| Atacama | Jujuy | 2,802 | Quechua |

| Ava Guaraní ( Chiriguanos ) | Jujuy, Salta, Corrientes, Misiones, Entre Ríos, Santa Fe, Buenos Aires | 19,828 | Guaraní |

| Chané | Salta | 2,097 | Arawak |

| Charrúa | Entre Ríos | 676 | Pampeano-Patagónico |

| Chorote | Salta | 2.147 | Mataco-Mataguayo |

| Chulupí | Formosa, Salta | 440 | Mataco-Mataguayo |

| Comechingón | Cordoba | 5.119 | Huarpes or standalone |

| Diaguita / Diaguita-Calchaquí | Jujuy, Salta, Tucumán, Catamarca, Córdoba, La Rioja, Santiago del Estero, Santa Fe, Buenos Aires | 25,682 | independent |

| Guaraní | Jujuy, Salta, Corrientes, Misiones, Santa Fe, Entre Ríos, Buenos Aires | 18,172 | Guaraní |

| Huarpe | Mendoza, San Juan, San Luis, Buenos Aires | 13,838 | independent |

| Kolla | Jujuy, Salta, Buenos Aires | 63,848 | Quechua / Aymara (Andean peoples) |

| Mapuche | Chubut, Neuquén, Río Negro, Santa Cruz, Tierra del Fuego, La Pampa, Buenos Aires | 104,988 | Pampeano-Patagónico (in most publications, origin unclear) |

| Mbyá-guaraní | Misiones | 4,083 | Guaraní |

| Mocoví | Chaco, Santa Fe | 12,145 | Guaycurú |

| Omahuaca | Jujuy | 1,370 | Quechua |

| Ona (Selk'Nam) | Tierra del Fuego, Buenos Aires | 505 | Pampeano-Patagónico |

| Pilagá | Formosa | 3,948 | Guaycurú |

| Quechua | Jujuy | 343 | Quechua |

| Creeper | La Pampa, Buenos Aires | 5,899 | Pampeano-Patagónico |

| Sanavirón | Cordoba | 528 | independent |

| Tapestries | Salta | 484 | Guaycurú or standalone |

| Tehuelche | Chubut, Santa Cruz, Buenos Aires | 5,937 | Pampeano-Patagónico |

| Toba | Chaco, Formosa, Santa Fe, Buenos Aires | 62,047 | Guaycurú |

| Tupi Guarani | Jujuy, Salta, Corrientes, Misiones, Entre Ríos, Buenos Aires | 15,117 | Guaraní |

| Wichi (Mataco) | Chaco, Formosa, Salta | 36,135 | Mataco-Mataguayo |

| All in all | 403.125 | ||

Settlement and cultures until the arrival of the Spaniards

It is still a matter of dispute to this day when the continent of America was first colonized by humans. For a long time the so-called theory of late settlement , also known as the Clovis consensus , was dominant , according to which around 14,000 BC. BC people first migrated from Asia to America via the Bering Strait . In contrast to this is the theory of early settlement , which assumes that this was already between 50,000 and 30,000 BC. A migration to America took place in the 3rd century BC, whereby the proponents of this theory consider not only a settlement via the Bering Strait possible, but also by seafaring peoples from Australia or Polynesia as well as from Greenland . This would also challenge the theory that South America was colonized from North America - it could also be independent migrations of multiple peoples.

The earliest evidence of human settlement on the territory of Argentina and neighboring countries seems to support the theory of early settlement. Thus the archaeological site of is Monte Verde from the extreme south of Chile, according to a study that has not yet confirmed beyond doubt, to 33,000 v. Dated (the date has been proven beyond doubt 13,000 BC). It seems to support the theory that immigration to Argentina did not come from North America but from southern Patagonia. The oldest site in Argentina itself is the Piedra Museo in the province of Santa Cruz, which dates back to 13,000 BC. Is dated.

Pampas and Patagonia

Based on the findings so far, it is assumed that the Patagonian region was the first on the territory of what is now Argentina to be inhabited by humans (probably from around 14,000 BC). In addition to the Piedra Museo, the site of Los Toldos (10,500 BC), also in the province of Santa Cruz, is of importance. It was in this region that the Toldense culture developed, from which arrowheads and bone tools have been preserved. Their representatives were nomadic hunters and gatherers. In the same region is the Cueva de las Manos , whose oldest cave paintings date back to 7300 BC. To be dated. Around 9000 BC The pampas were probably settled in the 4th century BC, the oldest finds of tools made of stone and ceramics (approx. 4000 BC) are here in the area around today's city of Tandil (Province of Buenos Aires ).

The Casapedrense culture, from which hunting weapons were found, developed between 7000 and 4000 BC. BC She was probably specialized in guanaco hunting . This culture was the forerunner of the Tehuelche culture, which over the centuries conquered almost the entire Patagonian region. They lived as nomads; in winter in valleys and on the coasts, in summer on the mountains and mesetas.

In Tierra del Fuego lived around 6000 BC. The Yaganes or Yámanas , who had their settlement center in the region of the Beagle Channel and lived mainly from fishing. They were characterized by a way of life on the water and only occasionally went ashore. They had fire pits on their canoes to protect themselves from the cold and to fry the fish. In the 14th century the island was invaded by the Selk'nam or Onas , who were a split off from the Tehuelche; However, unlike the Yámanas, they settled in the flat northern part.

West, Central and Northwest Argentina

The mountainous northwest half of what is now Argentina was probably built around 7000 BC. It was settled much later than the Pampas and Patagonia. The oldest finds come from the north of today's province of Córdoba and from San Luis ( Ayamapatín and Inti Huasi ), both from around 6000 BC. The Tafí culture in the province of Tucumán , which left numerous menhirs (worked rocks) in the subandine mountains near the town of Tafí del Valle , probably originated at this time.

Somewhat more recent (800–650 BC) is the La Aguada culture in what is now the provinces of Catamarca , La Rioja and San Juan . This culture dominated the processing of bronze ; she was sedentary and already farming.

The Diaguitas emerged as the dominant culture in the region in the course of the first centuries AD . They had their epicenter in the Calchaquí Valley (on the border between the provinces of Tucumán, Salta and Catamarca). They operated artificial irrigation and, together with the groups dominated by the Incas, were probably the most advanced civilization when the Spaniards arrived.

Mesopotamia and Chaco

The oldest culture in the area of today's Mesopotamias was probably the Alto-Paraná culture around 4000 BC. The region of northeast Argentina was then affected by numerous migrations. Both the Guaycurús from southern Patagonia and the Guaraníes from the Amazon region immigrated to this area. In contrast to the rest of the country, a really sedentary culture could not develop in this region. Although the Guaycurúes, Matacos and Guaraníes mastered simple farming techniques, they nonetheless remained semi-nomads and were unable to achieve any significant technological progress until the arrival of the Spaniards. The reason was probably the poor quality of the soil in the region, which is why hunting and collecting fruits was more advantageous than the development of complex agriculture. Only the ethnic groups that came into contact with the Andean peoples (mainly Guaraníes, now called Chiriguanos ) were able to develop a sedentary way of life.

The Conquista and the decline of Indian cultures

See also: History of Argentina

The Conquista, the conquest of American territory by the Spaniards and later by the newly independent nations of South America, had an unusually long duration on the territory of Argentina. Even if the Spaniards settled in the 16th century, numerous peoples offered them tough resistance until the beginning of the 20th century; Until well into the 19th century, the state dominance of Argentina was only really exercised in the vicinity of the cities. Many peoples of the Chaco, the Pampas and Patagonia based their power on the horse that they had either taken over from the Mapuche or the Spaniards or that came from captured feral " Cimarrones ". In 1919 there was a military conflict with the Toba Indians in the province of Chaco, the Battle of Nabalpi . Better known is the resistance of the Mapuche and the peoples affected by the Araucanization in southern Argentina, which, however, were already subjugated around 1880.

It should be mentioned that the Conquista was by no means always a clear argument between “Spaniards” (or later “Argentines”) and “Indians”. On the one hand, numerous groups of immigrants, especially the Welsh in Patagonia, maintained friendly relations with the Indians and also mixed strongly with them. Second, the military strategist of the Spaniards and Argentines took to the 19th century, during the conquest of the Pampas and Patagonia frequently alliances with fellow Indian groups - even in the conflict between "Unitarians" and "federalists" between 1820 and 1880. Only in the conquest of the desert ( Conquista del Desierto) In 1877/78 “the Indian” was generally viewed as an enemy and the goal of subjugating these peoples was realized, which ultimately degenerated into a systematic genocide .

First contacts

The first contact of Europeans with the indigenous peoples of Argentina took place in 1516. The expedition of Juan Díaz de Solís encountered the Het near what is now Buenos Aires while looking for a sea connection between the Atlantic and Pacific . In 1520 the expedition of Ferdinand Magellan took place, who met the Tehuelches on the Patagonian coast and gave them the name patagones ("big feet ") because of their supposedly large feet . While the contact between Magalhaes and the Tehuelches was largely peaceful, there was a first armed conflict at Díaz de Solís, in which de Solís and other members of the expedition were killed by the Indians.

In the first half of the 16th century, the Spaniards founded two fortifications: 1527 Sancti Spiritu (50 km north of today's Rosario ) and 1536 Santa María del Buen Ayre (today's Buenos Aires ). Both settlements had to be abandoned after a few years, as relations with the Het, although initially peaceful, quickly resulted in conflict. Santa María del Buen Ayre was literally besieged by the Het because of differences in trade, so that a food shortage occurred, to which numerous colonizers fell victim and which forced the Spanish to give up the settlement in 1541. Part of this expedition later founded Asunción , today's capital of Paraguay .

Colonization and missionary activity

Independent of these colonization attempts, the territory of Argentina was also colonized from the Peru region. The Spaniards founded numerous fortresses and settlements in northwest Argentina (including Santiago del Estero and Córdoba ). Although the Indians of this region offered bitter resistance, large parts were quickly subjugated and the so-called encomienda system was set up. The encomiendas were regions that were placed under the rule of a Spaniard to whom the Indians were a slave. Numerous Indian tribes were exploited as cheap labor in agriculture. Because of the poor conditions, this led to the first genocide on the territory of what is now Argentina, a large number of the Indians died.

At the same time, numerous missionaries came to the Spanish colonies in South America. Particularly important were the Jesuits , who from 1604 in the northeast ( Misiones ) in so-called reductions - closed settlements - offered the Guaraní living there protection from being exploited as cheap labor by large landowners, but also converted them to Christianity. Also because of the success of these reductions, which quickly spread to the interests of the Spaniards, the Jesuits were expelled from South America in 1767 and all reductions were closed. A well-known testimony to this era are the ruins of the Reduction of San Ignacio Mini . Missionaries were also active in the north-west, helping to spread not only Christianity, but also Quechua among the smaller Indian groups in this region.

While the large Indian tribes in the north and center of Argentina could be subjugated relatively quickly, the south remained in Indian hands until well into the 19th century. There the culture of the nomadic Tehuelche first spread (in the 17th century), and then that of the technologically advanced, sedentary Mapuche. Missionary activity on the part of the Europeans also began in Patagonia, for example in Tierra del Fuego by the Salesians of Don Bosco , but not until the end of the 19th century, much later than in the rest of the country. Although their goal, in addition to their conversion to Christianity, was to protect the Indians from exploitation by large landowners, they contributed to the decline and in some cases to extermination through the spread of diseases and an acculturation of the peoples through the adaptation to a Christian-Western way of life of Indian cultures.

Campaigns in the 19th century

After the independence of Argentina in 1816, the attempts to bring the south of the country under the control of the European dominated state power increased. This took the form of two large-scale campaigns. However, the conquest of this region was extremely slow.

The first campaign took place in 1833 under Juan Manuel de Rosas . The immediate goal was to end the continuous attacks by the Ranqueles under their ruler Yanquetruz in the north of the province of Buenos Aires . Rosas allied itself with parts of the Tehuelche and Mapuche, who were also enemies with Yanquetruz. The campaign started south from Buenos Aires, Córdoba and Mendoza. Rosas was able to defeat Yanquetruz, but not achieve his real goal, the subjugation of all Patagonian tribes.

The second campaign, known as the Conquista del Desierto ( Desert Conquest ), was carried out by Julio Argentino Roca in 1877 and 1878. In contrast to Rosas, Roca was not interested in alliances with friendly Indian tribes, his goal was the final subjugation of this population group. From Rosas, however, he took over the procedure from the three centers of Buenos Aires, Córdoba and Mendoza. From Roca's point of view, the campaign was successful: Almost all of the resistance in northern Patagonia and the southern pampas was banned. From the Indian point of view, however, the campaign can be described as genocide , as a very large part of the population lost their lives in it, either in the fighting themselves or through the sieges by Roca's armed forces, which led to famine. Many Indians were also resettled as slave labor in other provinces, where many of them succumbed to the poor conditions. The fact that Roca continues to be revered as a national hero in Argentina today is therefore increasingly meeting with fierce resistance among the native American Indians.

After Roca there were only a few military clashes with the remaining Indians, most of them integrated themselves into the Argentine state without resistance. The only other sources of conflict besides Patagonia were parts of the Gran Chaco , which was only very sparsely populated by Europeans and therefore allowed the presence of tribes like the Wichí and Toba with practically no contact with the rest of the population. A wave of violence between Indians and colonists at the beginning of the 20th century led to the Napalpí massacre in 1924 , in which between 200 and 400 people were killed.

Current situation

The Indians in Argentina today are a fringe group with particularly striking social problems. There are numerous laws at both federal and provincial level to protect their culture, but these are not or only poorly implemented; including an amendment to the Argentine Constitution of 1994, which guarantees the Indians special protection through the Argentine Congress, bilingual and bicultural education and the transfer of land to the communities.

Living situation

About two thirds of the Indians of Argentina live in their traditional settlement areas, the rest as immigrants in the big cities, of which a large number are foreigners (especially from Bolivia , Paraguay and Peru ). This migration is probably one of the reasons for the discrepancy between the official estimates of the number of Indians and the estimates of the Indian organizations, as the urban Indians usually assimilate quickly to the prevailing European dominated culture and therefore often no longer call themselves Indians. Even Spanish-speaking Indians in the original settlement areas often no longer refer to themselves as Indians, partly out of fear of discrimination.

Some of the Indian groups live in reservations where their culture enjoys special protection. However, these are often in poorly accessible areas that are not very suitable for agriculture, and the laws to protect the Indians in culture are rarely implemented in concrete measures.

Numerous Indian groups are involved in legal disputes over their territory, and their opponents are often large landowners. The reason is that many of today's legally binding land tenure claims in Argentina go back to land distributions among the conquistadors in the colonial era and in the 19th century, in which the Indians were not taken into account - their land was also distributed. Many of these claims have only recently been implemented (for example through fencing), which creates conflicts with the Indian groups. Since there is a law in Argentina according to which every resident of a property can claim it as his own after 20 years of uninterrupted occupation, the courts are increasingly making decisions in the interests of the Indians. Some of them also live on state-owned land, which has been given back their land piece by piece, especially since democratization (1983). Despite these successes, a large number of Indians continue to have problems with the legality of their property.

economy

Even if there are no official data on this, it can be assumed that the indigenous population in Argentina is far more affected by poverty and other social problems than the rest of Argentines . The poverty rate in the areas of the country that are particularly inhabited by Indians is usually significantly higher than in the rest of Argentina, and unemployment is often 50–80%.

Many Indians continue to live on their traditional forms of economy, such as agriculture and fishing. Cultivation on small plots dominates, which is often only sufficient for subsistence . A few Indian groups in the northeast are still semi-nomads, but this way of life is slowly dying out due to the increasing contact with European-born Argentines and their infrastructure (e.g. roads, settlements).

There are also numerous Indians who work as cheap labor for Argentinians of European descent. In the Andean northwest, for example, many Indians and mestizos are employed in mining , sometimes under very poor conditions. In the flat part of northern Argentina, most of them work in industrial agriculture, while in Patagonia many work in oil production. The Indians who migrated to the big cities are largely employed in the informal sector and in trade.

Many Indians today are also dependent on government welfare, especially in areas with high poverty rates such as the Formosa province . In this province, suspicions were repeatedly expressed that these social plans were intended to bind the Indians to a particular political party, and in the event of a non-pro-government election the plans were withdrawn.

education

The educational situation of the Indians in Argentina is worse than that of the inhabitants of European descent. Since the INDEC's 2004 special census, concrete data have been available that show that most indigenous ethnic groups have a significantly higher illiteracy rate and lower school enrollment rates than the rest of the population.

The situation of the Indians in northeast Argentina is particularly precarious, as they live mainly in isolation in independent communities. For example, 30% of the Mbya-Guaraní in Misiones are illiterate (national average: 2.7%). 16.5% of them (between 5 and 29 years of age) have never attended school or other educational institution. Also among the Wichi in Formosa and Chaco as well as the Toba and Pilagá the illiteracy rate is around 20% or higher. At the other extreme are the - now completely Spanish-speaking - Comechingones in Córdoba, of which 16.6% even more people have a university degree than the national average (11.8%). Both cases mark a clear tendency: the greater the geographical and cultural isolation of an Indian group from the rest of the population, the poorer the group's educational situation.

In the opinion of many critics, the poor educational situation is also a result of a lack of instruction in the native language of the Indian groups. A law has guaranteed the Indians since 1984 bilingual education in primary and secondary schools. So far, however, there are very few schools with bilingual instruction. In most schools in Indian areas there is only one bilingual assistant who is supposed to be at the side of the Spanish-speaking teacher if a child has language problems but is often abused in practice as a cleaner or orderly. Furthermore, there are hardly any educational offers for multilingual teachers, and the school curriculum is not adapted to the situation of the Indians.

In 2002 only in the provinces of Chaco and Formosa were there attempts to institutionalize bilingual teaching in schools in Indian areas, which were implemented with the help of non-governmental organizations.

languages

Of the people living in Argentina who call themselves indígenas (Indians), the majority are Spanish-speaking, especially among the largest groups, the Kolla in Jujuy and Salta and the Mapuche in Neuquén and Río Negro, where only 1.5 and 4 respectively .5% describe their original language as their mother tongue, and even fewer (0.7 and 2.1%) communicate mainly in these languages. In some smaller groups, especially those in the northeast of Argentina, on the other hand, over 90% kept their original language as their mother tongue, the largest group with a predominant original mother tongue are the approximately 35,000 Wichi in Formosa and Chaco with 90.8% native speakers. On the other hand, Indian languages are also spoken in some areas by non-Indians and so-called mestizos (people with European and Indian descent), for example in the case of Quichua in Santiago del Estero and Guaraní in Corrientes, where this language has been recognized as an alternative official language since 2004 is.

The following indigenous languages are spoken in Argentina today:

-

Tupí-Guarani family

- Mbyá-Guaraní (Corrientes, Misiones), around 3,000 speakers in 2002

- Western Argentine Guaraní , also Chiriguano (Salta, Jujuy), about 15,000 speakers

- Kaiwá (Northeast Argentina), 512 speakers

- Chiripá (Northeast Argentina)

- Tapieté (Salta), about 100 speakers in a single village near Tartagal

-

Mataco-Guaycurú family

- Toba (Chaco, Formosa), 19,810 speakers

- Toba-Pilagá or Pilagá (Formosa, Chaco, Salta), approx. 2000 speakers

- Wichí lhamtés vejoz (Salta, Jujuy, Formosa, Chaco), around 25,000 speakers

- Wichí Ihamtés güisnay (Formosa), around 15,000 speakers on the banks of the Río Pilcomayo

- Wichí Ihamtés nocten (Salta), approx. 100 speakers near the Argentine-Bolivian border

- Nivaclé or chulupí (northeast of Salta), about 200 speakers

- Mocoví (Chaco, Santa Fe), 4525 speakers

- Chorote iyojwa'ja (northeast of Salta), about 800 speakers

- Chorote iyo'wujwa (Salta), about 1500 speakers

-

Quechua family :

- Central Bolivian Quechua , a modification of Quechua IIc , (Jujuy, Salta, some large cities), approx. 855,000 speakers, most of them immigrants from Bolivia.

- Argentine Quechua , also Quichua or Quechua Santiagueño (Santiago del Estero), modification of Quechua IIc, around 60,000 speakers

- Mapudungun (Neuquén, Río Negro, Chubut), about 100,000 speakers

- Aymara (Jujuy, Salta, some major cities), no speaker count data available, is spoken mainly by immigrants from Bolivia.

There are only a few speakers of the language groups Tehuelche (Patagonia), Ona (Tierra del Fuego), Vilela (Chaco) and Puelche (Neuquén), these are on the verge of extinction or are already extinct.

Many languages of the original population of today's Argentina went through this process of extinction shortly after the arrival of the Spaniards. Not only the Spaniards themselves were a decisive factor, but also the Mapuche Indians, who were able to expand their cultural and linguistic area in the course of the 16th to 19th centuries to the entire south of Argentina and were only defeated militarily in the desert campaign of 1876–1878 and were subjugated or systematically exterminated. Especially among the pampa peoples who were not sedentary and Araucanized early on ( Het or Querandíes), one can only speculate about the existence of one or more languages of their own today.

credentials

- ↑ Cuadro P44. Total del país. Población indígena o descendiente de pueblos indígenas u originarios en viviendas particulares por sexo, según edad en años simples y grupos quinquenales de edad. Año 2010 ( MS Excel ; 38 kB), INDEC website

- ↑ a b Processed data from the 2001 census of the INDEC ( Special Census Encuesta Complementaria sobre Pueblos Indígenas (ECPI) 2004-2005 ( Memento of the original from February 16, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked Original and archive link according to instructions and then remove this note. )

- ↑ First results of the special ECPI census of the INDEC ( Memento of the original from February 16, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Article on the study (Spanish) ( Memento of the original dated August 4, 2012 in the web archive archive.today ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Guia YPF, Volume 6 Patagonia y Antártida Argentina , 1998

- ↑ Charles C. Mann, 1491, Taurus, Madrid 2006, pp. 207–228

- ↑ Monte Verde website ( Memento of November 18, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Dirk Bruns: Argentina, Mundo-Verlag 1988, p. 424

- ↑ Article in the Criterio magazine ( Memento of the original from September 29, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ All data in this section are based on the 2001 INDEC census .

- ↑ The two paragraphs are based on the essay "Una Perspectiva sobre los Pueblos Indígenas en Argentina" by Morita Carrasco, 2002, p. 22

- ↑ Data in this section: INDEC special census , 2004

- ↑ Source: Ethnologue , based on various studies

literature

- Marisa Censabella: Las lenguas indígenas de la Argentina: una mirada actual . Eudeba, Buenos Aires 1999, ISBN 950-23-0956-1 .