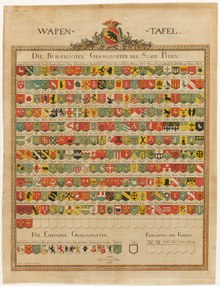

Coat of arms of the bourgeois families of the city of Bern

The coats of arms of the bourgeois families of the city of Bern developed in the Middle Ages, later consolidated and were regulated by the authorities in 1684.

middle Ages

The earliest coats of arms of burgers in the city of Bern are those of noble families who became citizens of Bern, such as the Balm, Bubenberg , Bennenwil , Kienberg and Krauchthal . Because all citizens of the city of Bern were free , they were all entitled to seal certificates as witnesses. The seals of the non-aristocratic citizens usually only showed a coat of arms, in contrast to the seals of the nobility, which were usually designed as a full coat of arms with helmet and jewel or as a rider's seal . The oldest surviving seal of a Bern burger is that of Johannes de Watenwile civis bernensis from 1300, which has a rose . A deceased's seal had to be given to the council. As a result, coats of arms were often only used by one person (as a personal coat of arms) in the 14th century. An example of this are the father and sons of the notable Münzer family , who all had three different seals. Notable families increasingly had coats of arms like aristocrats, some were raised to the nobility, for example the herdsmen of Münsingen . These genders used the designation noble servant as a demarcation to the handicraft families. Master craftsmen also imitated the use of coats of arms by using tools or house signs in the form of coats of arms. Early coats of arms of bourgeois families were used in addition to the seal to mark houses, grave slabs and church foundations.

Early modern age

By 1400, the practice of using coats of arms among the non-aristocratic families of Bern was largely consolidated. Families like the Diesbach , Matter, Wabern, Wattenwyl or Zigerli became ennobled by acquiring dominions , letters of nobility and a corresponding standard of living. Part of the standard of living was the use of a noble coat of arms, which one received in a coat of arms letter or acquired arbitrarily like the von Wabern family of tanners, who transformed their coat of arms from crossed tanner knives into a St. Andrew's cross . Niklaus von Wattenwyl (1453) or Clewi von Diesbach (1434) received heraldic letters. In addition to the emperor, for example, the dean Albrecht von Bonstetten was also able to issue coats of arms. One who made use of it was Rudolf Herport from Willisau (1494).

The burgers put their coats of arms in churches (altars, keystones , glass paintings, etc.). First heraldic cycles are likely to have existed in the rooms of the societies and guilds. An early series of civic coats of arms is the dance of death by Niklaus Manuel from 1516/17 , which is provided with coats of arms of the donors of the picture sequence. Crest cycles also emerged on the seats of the bailiff, whether as frescoes ( Chillon Castle ) or wooden panels ( Schloss Buren , Burgdorf Palace , Castle Landshut ). The glass painter Thuringia Walther published the first Bernese coat of arms booklet in print in 1612. Other artists such as Hans Ulrich Fisch , Wilhelm Stettler or Johann Rudolf Huber created civil heraldic books for themselves or on behalf of them. Several printed coats of arms were created in the 18th century. In 1742 David Herrliberger published a sheet with the coats of arms of the mayors, beginning with Walter von Wädenswil (1223). Around 1745 Johann Heinrich Freitag published a large sheet with the coats of arms of all regimental families, permanent residents and offices. In the same year, Samuel Küpfer also published a plaque with the coats of arms of the bourgeois families.

The patrician families used to improve their coats of arms on a large scale, especially in the post-Reformation period, either by hand or through coats of arms letters. The imperial or royal coat of arms improvements often consisted of a crossing . The changes made by hand were expressed through the omission of tools or three-way genes in order to make the coat of arms look more noble, to erase the origin from the craft. In order to curb this practice, on November 24, 1684, the Great Council gave the Burgerkammer the order to record the coats of arms of the bourgeois families in registers, and in an unimproved form. The council commissioned Brandolf Egger in 1711 with the creation of a new, official register of coats of arms of all genders eligible for regiment.

The time after 1798

With the fall of the city and republic of Bern, the legislation on the use of coats of arms fell. Improvements to the coat of arms were borne by the families, especially after 1831, when the families who were formerly capable of regiment began to separate themselves from the civil families who had been accepted since 1798. In 1829 Johann Emanuel Wyss published a printed book of arms, followed in 1836 by a small-format book of arms, which was intended in particular for collectors of seal impressions. In 1932, the civic community of Bern published the Folioband Wappenbuch der Stadt Bern, with the coats of arms of all living and extinct civil families, the coats of arms of the societies and guilds as well as the civil associations. The coats of arms were drawn by Paul Boesch and Bernhard von Rodt, the texts on the coats of arms were written by Hans Bloesch. In 2003 the coat of arms of the Burgergemeinde Bern appeared , which contains the coats of arms of all thriving families.

According to the ordinance on entries in the register of coats of arms of the civic community of Bern of May 8, 2006, all citizens of Bern are entitled to have their coat of arms entered in the civic register of arms. Entry in the register and principles of coat of arms are regulated in the ordinance. The citizens' commission is responsible for checking and entering in the register. This does not result in any special protection for civil coats of arms. The citizenship is obliged to use the registered family coat of arms in accordance with the ordinance.

See also

literature

- Edgar Hans Brunner: The change of coat of arms of the Brunner in Bern. In: Swiss archive for heraldry. Vol. 108, No. 2, 1994, pp. 142-150.

- Edgar H. Brunner: patriciate and nobility in old Bern. In: Bern journal for history and local history. Vol. 26, 1964, pp. 1-13, doi : 10.5169 / seals-244446 .

- Burgergemeinde Bern (Hrsg.): Book of coat of arms of the civil families of the city of Bern. Benteli, Bern-Bümpliz 1932.

- François de Capitani: Nobility, citizens and guilds in Bern in the 15th century. Stämpfli, Bern 1982, ISBN 3-7272-0491-5 .

- Jakob Otto Kehrli : The private law protection of the family coat of arms in Switzerland since the civil code came into force. In: Journal of the Bern Lawyers' Association. Vol. 60, No. 12, 1924, ISSN 0044-2127 , pp. 578-597.

- Manuel Kehrli: The Bernese coat of arms stone from 1706 in the town church of Zofingen. In: Zofinger Neujahrsblatt. 2011, ZDB -ID 351099-2 , pp. 13-18.

- Manuel Kehrli: "His mind is capable of anything". The painter, collector and art connoisseur Johann Rudolf Huber. 1668-1748. Schwabe, Basel 2010, ISBN 978-3-7965-2702-9 .

- Regula Ludi : The ancestral pride in the Bernese patriciate. Socio-historical background to coat of arms painting in the 17th century. In: Georges Herzog, Elisabeth Ryter, Johanna Strübin Rindisbacher (eds.): In the shadow of the golden age. Artist and client in the 17th century Bern. = A l'ombre de l'âge d'or. Volume 2: Essays. Kunstmuseum Bern, Bern 1995, ISBN 3-906628-06-X , pp. 35–48.

- Eduard von Rodt : Stand and coat of arms of the Bernese families. In: New Bernese paperback. Vol. 1, 1896, ZDB -ID 548108-9 , pp. 1-71, here pp. 60 f., Digitized .

- Berchtold Weber, Martin Ryser: Wappenbuch der Burgergemeinde Bern. Stämpfli, Bern 2003, ISBN 3-7272-1221-7 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ von Rodt 1896, p. 14.

- ↑ von Rodt 1896, p. 14.

- ↑ von Rodt 1896, p. 17.

- ↑ von Rodt 1896, p. 7.

- ↑ de Capitani 1982, fig. 33.

- ↑ von Rodt 1896, p. 27.

- ^ The Herport later became Burgers from Bern; von Rodt 1896, p. 32.

- ↑ Wappenbüchlein. Bern 1612 doi : 10.3931 / e-rara-7728 .

- ↑ Presenting throne and pillars of honor [...] , Burgerbibliothek Bern, Gr.B.68

- ↑ Presentation of the coat of arms of the high class as well as all other honorable families of the highly lobbies and Republic Bern , Burgerbibliothek Bern, Gr.D.50

- ↑ Coats of arms of all regimental families of the city of Bern (1745), Bern Burgerbibliothek, Gr.D.170

- ↑ Brunner 1964, p. 2; SSRQ BE V, p. 367 online

- ↑ Kehrli 2010, pp. 141–142; Book of Arms of the Citizens of the City of Bern, Vol. 1 (1711–1768), Bern Citizens Library , Mss.hhXII.359

- ↑ The design of the coat of arms was computerized. Every coat of arms is emblazoned, the historical comments on the coat of arms are almost entirely questionable. The coats of arms do not follow the list of the sexes in the directory of the citizens of the city of Bern , which is printed every five years. There are no coats of arms of the sexes such as the Daxelhofer or Haller .

- ↑ Civic Legal Collection , Ordinance on Entries in the Coat of Arms of the Civic Community of Bern (PDF, 181KB)