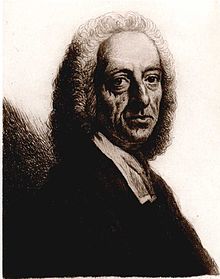

William Whiston

William Whiston (born December 9, 1667 in Norton , County Leicestershire , † August 22, 1752 in Kensington ) was an English theologian and physicist .

Life

Whiston enjoyed a private schooling, partly because of his fragile health, partly because he served as a writing aid to his blind father, an Anglican clergyman. After the death of his father, he entered Clare College in Cambridge , where he studied theology , but also became more and more involved in mathematics . In 1693 he received a scholarship from the university for this . After that, however, he first became a clergyman under John Moore (1646-1714), the Bishop of Ely, by whom he was appointed provost of Lowestoft in 1698 .

In 1701 he gave up his ecclesiastical position to become Newton's deputy in Cambridge, which he succeeded two years later on the Lucasian Chair of Mathematics. Here he carried out joint research with his junior professor Roger Cotes .

For several years he continued to write and preach with considerable success on mathematical and theological subjects. His studies, probably stimulated by Isaac Newton, led him to believe that Arianism was the belief of the early Church. In contrast to Newton and other colleagues, who only communicated this insight in the narrowest circle, for Whiston formation of opinion and publication went hand in hand. He soon became notorious for his nomn-confirmistic beliefs, which the Church viewed as heretical. Since all professors had to profess the Athanasian doctrine of the Trinity in writing , he was relieved of his professorship as an anti-Trinitarian and expelled from the university. He spent the rest of his life in incessant arguments of theological, mathematical, chronological and other kinds. Thus he successfully challenged Newton's chronological system of the Bible. He was on friendly terms with the Unitarian Thomas Emlyn .

After losing his professorship, he moved to London and lived on the income from an estate. To improve the financial situation, he teamed up with Francis Hauksbee . From 1713 they gave lectures on mechanics, hydrostatics, pneumatics and optics in London coffee houses. They enjoyed great popularity, also because they were associated with experimental demonstrations. The course manual published in 1714 even served as a template for courses at Oxford University.

Whiston's last publication was his three-volume memoir (1749–1750), which did not get the attention it deserved. This work was primarily a collection of strange anecdotes and descriptions of the religious and moral tendencies of the time. In 1747 he left the Anglican Church and switched to the Baptists. He died on August 22, 1752 in the house of Samuel Barker, the husband of his daughter Sarah. His wife Ruth had died in 1751.

The Dorsa Whiston on the Earth's moon is named after him.

plant

William Whiston is the author of A New Theory of the Earth , a treatise on creationism and the geology of flooding. In it he claimed that the biblical accounts in Genesis about the Flood could be scientifically explained and had a historical core. It relied on new scientific discoveries such as Newton's celestial mechanics and geological theories, which were then developed to substantiate the Bible. For example, he explains the flood as a god-directed comet , ideas that were revived by Immanuel Velikovsky , among others . This treatise has received high praise from both Isaac Newton and John Locke . Along with Edmund Halley, he was one of the first to think of comets as periodic phenomena. In his essay Astronomical Principles of Religion he advocated Halley's hollow earth theory and found evidence from the Bible beyond Halley that the inner worlds are also inhabited.

In 1736 he caused a stir among Londoners when he predicted that the world would end on October 13th of that year because a comet would hit the earth. The Archbishop of Canterbury had to publicly deny this prediction in order to reassure the public. Even so, many Londoners went to Hampstead to see the fall of London as the prelude to the Last Judgment. A humorous description can be found in Jonathan Swift .

He was also known for his annotated translations of the Antiquitates Judaicae and other works by Flavius Josephus .

Longitude problem

However, he tried unsuccessfully to solve the length problem . In 1714 he and the London mathematician Humphry Ditton approached Parliament with the proposal to offer a monetary prize to solve the problem of length. Newton, Samuel Clarke , Cotes and Halley supported the petition and Parliament offered a reward of £ 20,000 with the Longitude Act . The proposals submitted by Whiston and Ditton in 1714 were impractical, including a magnetic declination method . In 1718 he learned from the German geographer Christoph Eberhard a method originally developed by Christoph Semler using magnetic inclination . With the help of private sponsors, he was able to test the method on sea voyages, but it turned out to be inapplicable. The mathematical methods he developed for the creation of the isoclinic maps of southern England were way ahead of their time.

Publications

- A New Theory of the Earth, From its Original, to the Consummation of All Things, Where the Creation of the World in Six Days, the Universal Deluge, And the General Conflagration, As laid down in the Holy Scriptures, Are Shewn to be perfectly agreeable to reason and philosophy. London 1696.

- A Short View of the Chronology of the Old Testament, and of the Harmony of the Four Evangelists. Cambridge, 1702.

- An Essay on the Revelation of Saint John, So Far as Concerns the Past and Present Times. 1706.

- Arithmetica universalis. 1707, edition of Newton's lectures.

- Praelectiones Astronomicae Cantabrigiae in Scholis Habitae. London, 1707.

- Sermons and Essays. 1709.

- Praelectiones Physico-mathematicae Cantabrigiae, in Scholis Publicis Habitae. 1710.

- Primitive Christianity Revived. 1711-1712.

- Wilhelm Whistons ... Nova tellvris theoria, that is, New Contemplation of the Earth: after its origins and progression bit to the creation of all things, or, A thorough, clear and according to attached outline set up idea ... , translated from English by MMSVDM (Michael Swen) . Ludwig, Franckfurt [1713].

- with H. Ditton: A New Method of Discovering the Longitude at Sea and Land, Humbly Proposed to the Consideration of the Publick. London 1714.

- Astronomical Lectures. 1715.

- Astronomical Principles of Religion, Natural and Reveal'd. 1717.

- The longitude and latitude found by the inclinatory or dipping needle: wherein the laws of magnetism are also discovered; To which is prefix'd, an historical preface; and to which is subjoin'd, Mr. Robert Norman's New attractive, or account of the first invention of the dipping needle. London 1721.

- Life of Samuel Clarke. 1730.

- The Astronomical Year: Or an Account of the Great Year MDCCXXXVI. Particularly of the Late Comet, Which was foretold by Sir Isaac Newton ... London, 1737.

- Primitive New Testament. 1745.

- Memoirs of the Life and Writings of Mr. William Whiston. London, 1753.

- with Andreas Tacquet: 1 and 2.: Elementa Euclidea Geometriae planae AC solidae selecta EX Archimede theoremata ejusdemque Trigonometria plana. Venice 1746.

- The Works of Flavius Josephus, the Learned and Authentic Jewish Historian and Celebrated Warrior.

- An Experimental Course of Astronomy; Proposed by Mr. Whiston and Mr. Hauksbee.

credentials

- J. Swift: A True and Faithful Narrative of what passed in London on a Rumor of the Day of Judgment. (= Miscellanies. Vol. Iii)

- RJ Howarth: Fitting geomagnetic fields before the invention of least squares. II. William Whiston's isoclinic maps of southern England (1719 and 1721). In: Ann. of Sci. Volume 60, No. 1, 2003, pp. 63-84.

Web links

- Literature by and about William Whiston in the catalog of the German National Library

- William Whiston on the Gutenberg project

- John J. O'Connor, Edmund F. Robertson : William Whiston. In: MacTutor History of Mathematics archive .

- Bibliography ( Memento from July 26, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- Halley's Hollow Earth Theory ( Memento from February 7, 2006 in the Internet Archive )

- London Coffee houses and mathematics

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Whiston, William |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | English theologian and physicist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | December 9, 1667 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Norton in County Leicestershire |

| DATE OF DEATH | August 22, 1752 |

| Place of death | Kensington |