Yamasee War

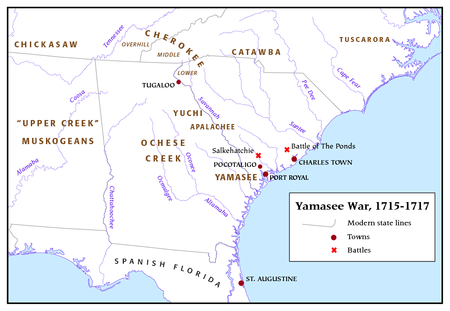

The Yamasee War (English Yamasee War , also spelled Yemassee War ) was a conflict between the province of Carolina and various Native American tribes , including the Yamasee , Creek , Cherokee , Chickasaw , Catawba , Apalachee , Apalachicola , and Yuchi, which lasted from 1715 to 1717 , Savannah River Shawnee , Congaree , Waxhaw , Pee Dee , Cape Fear Indians , Cheraw and many others. Some of these Indian groups played a negligible role in the conflict, while other tribes raided all of what is now South Carolina . Hundreds of settlers were killed and many settlements destroyed. Traders who bartered with the Indians and mostly lived among them were killed throughout the southeast of the country. In the course of the war, large parts of the populated area of South Carolina were abandoned. The colonists fled to Charles Town , where supplies ran short and people starved to death. During 1715, the province's survival was in doubt, only when the Cherokee allied with the Carolinians in 1716 and attacked the Creek did the tide turn. The last major enemies of South Carolina withdrew from the conflict in 1717, leaving the shattered colony a fragile peace.

The Yamasee War was one of the most threatening wars for the development of colonial America and changed the colony. As a result of this conflict, European supremacy was faced with one of its most serious challenges from the American Indians. For over a year, South Carolina had the real possibility of being completely destroyed. Over seven percent of the entire white population of South Carolina was killed, so the war has claimed more victims than King Philip's War , often described as the bloodiest in the history of the Indian Wars .

The geopolitical situation changed radically, both for the British , Spanish and French colonies as well as for the indigenous peoples of the Southeast, especially for South Carolina this armed conflict was a key moment in its history. The war marks the end of the early colonization of the American South. In addition, as a result of the war, several Indian tribes formed new alliances and Indian nations emerged, for example the Catawba and the Creek Bund .

The causes of the war are complex and present themselves differently for the many tribes involved, as did the participation. Some tribes fought to the bitter end, others were more casually involved, some tribes divided while others switched sides. No central and simple reason for the outbreak of war can be found, but some of the determining factors were the trading system, the abuse of trade agreements, the slave trade with Indians, the excessive hunting of deer for the deer skin trade, the increasing debts of the Indians at the same time increasing prosperity of the settlers, attacks on Indian-occupied land and the increasing expansion of rice plantations . The growing influence of the French, who offered an alternative to British traders, and the long and close ties of the natives to Spanish-influenced Florida also played a role . The competition for power within the Indian tribes promoted the war as well as an increasing and stable communication between the tribes as well as previous military experiences with allied tribes that were not very close before.

Prehistory and background

Overview: Timeline of the Indian Wars

Dissatisfaction with the colonial power

Many Native American tribes were involved in the conflict, and each and every one of these tribes had individual reasons for participating in the uprising against South Carolina. Overall, the finding that the trade and the abuse of trade relations between the British and the Indians led to tension is not in all cases so decisive that this could be identified as the sole cause of the increasing unrest among the tribes. The increasing expansion of plantations and settlements posed a further threat to the habitat of some peoples. It is unclear whether and how the Spaniards who colonized Florida and the French, with their increasing interest in the new world, were involved in stirring up further discontent. Both nations offered the Indians an alternative to the British immigrants who predominated in their settlement area. Another point was the striving for power of individual tribes, most recently manifested in the Tuscarora War that took place shortly before , which had shifted the balance of power within the Indian tribal principalities and tribes of the southeast and which opened up new connections and more intensive communication between the tribes for the Indians.

Recent research, such as that presented by William L. Ramsey in The Yamasee War: A Study of Culture, Economy, and Conflict in the Colonial South , assumes that an additional aspect is the social differences and mutual incomprehension between the European settlers and the indigenous people of the region. For example, the British settlers did not respect the Cherokee's socially ostracized disregard for women, and there were multiple attacks and rape by British traders, who the tribes saw as an attack on their tradition and culture.

Consequences of the Tuscarora War

The Tuscarora War and its far-reaching consequences played a crucial role in the outbreak of the Yamasee War. In the fight against the Tuscarora , who began to attack the settlements of the Province of North Carolina in 1711 , the Province of South Carolina raised armies, which consisted largely of indigenous troops. These Indians were recruited in a large area from different tribes, sometimes from groups that were traditionally enemies with one another. Tribes that provided soldiers for the Army of South Carolina included the Yamasee, Catawba, Yuchi, Apalachee, Cusabo , Wateree , Sugeree , Waxhaw, Congaree, Pee Dee, Cape Fear, Cheraw, Saura , Cherokee and various Creek groups.

This military cooperation under the guidance of the colonial officers ensured closer ties and significantly intensified communication between the tribes involved. In this context, the Indians recognized the disagreement in the structure of the provinces and the weaknesses of the individual British colonies, especially when South Carolina, North Carolina and Virginia almost fell out over various aspects of the Tuscarora War. In effect, all the tribes that fought on the South Carolina's side in the Tuscarora War were among the colony's allied attackers during the Yamasee War, which took place only two to three years later. By the end of the Tuscarora War, the population of the powerful Tuscarora tribe had lost well over 1,000 members and largely withdrawn, giving other tribes the opportunity to better position themselves.

Yamasee

The Yamasee, which are mostly described as a tribe, which generally implies a political and ethnic unit, were not a single people, but consisted of the survivors and the remnants of other tribes and tribal principalities. These included, for example, the Guale and groups who came from the provinces of Tama and Ocute in inland Georgia. The Yamasee developed during the 17th century in the contested border area between South Carolina and the Spanish colony of Florida. Initially, they were allies of the Spaniards, but moved north in the late 17th century and soon became South Carolina's most important Native American allies. The tribe lived near the mouth of the Savannah River and in the Port Royal Sound area .

The Yamasee benefited from their ties with the British for years, but by 1715 it was difficult for the tribe to procure the two most sought-after commodities in trade with the British: deerskin and Native American slaves. So close to the settlement area of the colonists and with a strongly increased demand for deerskin, the deer in the territory of the Yamasee became rare. After the Tuscarora War, the possibilities of raiding other tribes and robbing the slaves much needed by the British were also limited. As a result, the tribe became increasingly unimportant for the colony and borrowed from the British traders, as the British trade goods continued to be delivered on credit to the Indians. In 1715, rice cultivation was booming in South Carolina, and large areas of land suitable for cultivation were taken over. Part of this land had been awarded to the Yamasee after the Tuscarora War and was ideal for building rice plantations . Under these circumstances, the question for the Yamasee was not whether to fight, but when. It is not known whether the Yamasee were the driving force behind the seditious mood and plans for war among the Indians.

Role of the Ochese Creek and other tribes

The Ochese Creek, now known as Lower Creek , were probably instrumental in mobilizing support for the war among the other tribes. Each of the many tribes that eventually went to war had their own reasons as complex and deeply rooted in the past as the Yamasee. Although there was not a large conspiracy of many tribes planning a coordinated attack, the unrest among the tribes steadily increased and in the communication between the tribes a possible outbreak of war was discussed. In the spring of 1715 the growing mood in favor of war had become so unsettling that some Indians warned the colonists of the impending danger. These warnings indicated Ochese Creek as a major aggressor.

Course of the war

Pocotaligo massacre

When the warnings of a possible Indian uprising involving the Ochese Creeks reached the government of South Carolina, they were taken seriously. A group of ambassadors was immediately dispatched to the main town of the Yamasee in Pocotaligo, not far from what is now Yemassee in South Carolina . They hoped to enlist the support of the Yamasee to arrange immediate negotiations with the leaders of Ochese Creek.

The group that traveled to Pocotaligo consisted of at least six men, including Samuel Warner and William Bray, who were sent by the "Board of Commissioners", the government of South Carolina. They were accompanied by Thomas Nairne and John Wright, two of the most important figures in the trade between the colony and the Indians. Two others, Seymour Burroughs and an unknown citizen of the colony, were also visitors to the Yamasee. When the delegation arrived in the village on April 14, 1715, rumors had preceded them that they had come to the Yamasee as spies and not as ambassadors. For three Indian chiefs, the village heads of Pocotaligo and Salkehatchie, another village of the tribe, as well as a warrior from Ochese Creek, the rumor of espionage was decisive. The apparently successful negotiations with those responsible for the tribes that day gave the ambassadors the feeling that they had successfully prevented an escalation.

The night the visitors slept, these three men adorned themselves with their war paint and then woke the delegation together with some of their supporters. Two of the six men escaped. Seymour Burroughs, although shot twice, reached the Port Royal area and alerted the population, while Nairne, Wright, Warner and Bray were murdered. The unknown Carolinier was also able to escape and hid in the nearby woods. There he watched Thomas Nairne slowly being tortured to death, an act of respect the Indians felt for one of their previous friends.

These events, which occurred in the morning hours of Good Friday on April 15, 1715, mark the beginning of the Lake Yamasee War. Although not all tribesmen supported war, there was obviously no other way. The Yamasee decided to do as much damage as possible and use the surprise effect before the anticipated reaction of Governor Charles Cravens and the South Carolina militia .

Attacks by the Yamasee and counterattacks by the colonists

The Yamasee quickly set up two groups of warriors, consisting of several hundred men, who set out on the day of the murders in Pocotaligo. One of the groups attacked the Port Royal settlements, but they had been warned by Seymour Burrough. Despite severe wounds, he had reached John Barnwell's plantation not far from Seabrook on his flight from the Indians and triggered the alarm. Coincidentally, a hijacked smuggler's ship was in the dock at Port Royal and by the time the Indians had reached the settlements, hundreds of settlers had already been brought to safety on the ship. Many other settlers had fled by canoe. The Indians set fire to the settlements and returned to Pototaligo.

The second group invaded the area of Saint Bartholomew's Parish in what is now Colleton County . In the more scattered homesteads and plantations, no alarm had been given about the expected attack, and so the warriors met completely surprised and largely defenseless colonists. The Indians plundered, set fire to plantations, took prisoners and killed over a hundred settlers and slaves. The surviving colonists fled to Charles Town. This attack hit the settlers hard, not only had all British traders in the region been killed, but the colony's previously valid border had also been destroyed.

The Yamasee War was the first real challenge facing the hastily assembled South Carolina militias . Governor Craven decided to split the militia into two attack forces. One, led by himself, was to be led against the village of Yamasee, the other, led by Barnwell, was to destroy Pocotagligo. Given the threat to their villages, the Indian warriors only had the option to gather their traditionally small groups of warriors and attack the militia under Craven's leadership, while the rest of the tribe fled south to seek shelter in makeshift forts . Near the Indian settlement of Salkehatchie on the banks of the Salkehatchie River , the Cravens militia and the Indians finally met in an open area. A classic field battle developed, which Craven and the officers of the militia had hoped for and which was extremely unsuitable for the Indians due to their preferred guerrilla tactics.

Several hundred warriors attacked the approximately 240 militiamen. The Yamasee tried to bypass the colonists, but could not achieve their goal. After several leading warriors were killed, the Indians fled the battlefield and disappeared into the nearby swamps. Although the casualties were the same on both sides, around 24 men, the battle was a clear victory for the settlers. Smaller groups of the militia forced the Yamasee to fight in further small skirmishes and won a number of other victories.

Barnwell and Alexander MacKay, who already had experience in wars against Indians, led their troops of around 140 strong men south. The Indian settlement that was the target of their attack had largely been evacuated. They found the tribesmen in a camp protected by palisades about seven kilometers from Pocotagligos and attacked the group of around 200 Yamasee who had withdrawn into the makeshift fort. After a group of Carolinians under the leadership of John Palmer, later known as the Indian warrior in the colonies, had crossed the palisades, the Yamasee decided to withdraw. Outside the camp, they were caught in an ambush by MacKay and another 100 men in the surrounding woods. Most of the Indians were killed or captured in this ambush, a small remainder escaped.

A smaller battle took place in the summer of 1715 and became known as the "Daufuskie Fight". A Carolinian boat crew managed to ambush a group of Yamasee and kill 35 Indians while losing only one man.

These important victories in the southern border area of the colony drove the Yamasee further south and after a short time the survivors of the tribe decided to move to the area around the Altamaha River . Further attacks by the Yamasee and a repopulation of the region around the Port Royal Sound were averted, although there were still occasional minor attacks by the Indians. With the expulsion of the Yamasee, the southern border was calmed, the focus of the war shifted to the northern and western border regions of South Carolina, which were threatened by the approximately 9,000 warriors of the Creek and their allies.

British traders died

While the Yamasee worried the settlers most in the first few weeks, British traders in the entire south-east were caught by Indians and mostly killed. At the beginning of the war there were around 100 traders in the region, around 90 of whom were killed in the first few weeks. Tribes involved in the killing of the traders included the Creek people (Ochese, Tallapoosa, Abeika, and Alabama tribes), the Apalachee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Catawba, and Cherokee.

Northern front

In the first month of the war, South Carolina hoped for support from the North American Indians, such as the Catawba. But the first news that came from the north was that the British traders under the Catawba and Cherokee had been killed. The Catawba and Cherokee had not attacked the merchants as early as the southern Indians, as the two tribes disagreed on which direction to take. But a number of events and rumors fueled growing hostility in the north. Some Virginia traders were later accused of inciting the Catawba and driving them to war with South Carolina. Notably, the Virginia traders were spared when the Catawba decided to kill the South Carolina traders.

In May 1715 the Catawba sent troops against South Carolina. A group of about 400 Catawba warriors, accompanied by 70 Cherokee, formed a force that terrorized northern South Carolina. In June, 90 cavalry men under Captain Thomas Barker rode north in response. The Indian troops found out about this in advance and managed to ambush Barker's troops, which were completely wiped out. Another group of the Catawba and Cherokee attacked a makeshift fort on Benjamin Schenkingh's plantation, killing around 20 people. After this attack, South Carolina no longer had a defensive position between the rebellious Indians in the north and the prosperous Goose Creek District north of Charles Town .

Before the Indian troops from the north could attack Charles Town themselves, most of the Cherokee returned to their settlements, having heard of important and decisive developments in their villages. The remaining Catawba suddenly found themselves facing a quickly assembled militia under the command of George Chickens. On June 13, 1715, the militia under Chicken set a trap for the Indian troops, this battle later became known as the Battle of the Ponds. The result was a defeat for the Indians, who, although excellent in guerrilla warfare , were not used to battles with opposing troops. After the Catawba returned to their villages, the situation was discussed again and the tribe opted for peace. In July 1715, diplomats from the Catawba reached Virginia to offer the British not only peace, but also military support for South Carolina.

Creek and Cherokee

The Ochese Creek were probably at least as much a part of the rioting as the Yamasee. When the war broke out, they immediately killed all South Carolina merchants who were in their area, as well as the rest of the Creek, the Choctaw, Chickasaw, and Cherokee. Several smaller tribes such as the Yuchi, Savannah River Shawnee, Apalachee and Apalachicola lay as a buffer between the Ochese Creek and South Carolina. In the summer of 1715, these tribes began a series of several successful raids on the populated areas of South Carolina. Although some oxen were involved in these attacks, they behaved rather cautiously after the Carolinians' counterattacks proved effective. The smaller groups of Indians fled the area of the Savannah River and many found refuge at Ochese Creek. It was there that the plans for the next phase of the war were finally developed.

The Upper Creek were not so determined to declare war on South Carolina, but they still had the utmost respect for Ochese Creek (Lower Creek). Participation in their campaign was quite conceivable for Upper Creek if a good offer for their participation. One point of the negotiations was the merchandise. English goods from South Carolina, including weapons, had become vital to all of the Creek tribes. With an imminent war against the British, the Creek became interested in the French and Spanish as potential trading partners. These were more than ready to supply the Creek, but could neither offer the quantity nor the quality that had previously been supplied by the British. Muskets, gunpowder, and bullets became particularly necessary in the event of a Creek invasion of South Carolina. The Upper Creek continued to resist war, but the Creek forged closer ties with the French and Spanish during the Yamasee War.

The Ochese Creek had other connections, for example to the Chickasaw and Cherokee. The Chickasaw, however, made peace with South Carolina immediately after killing the traders in their area. They had declared that the creek was responsible for the vendors killed in their settlements - an excuse South Carolina gladly accepted. This made the Cherokee's stance a strategically important point.

These were split, the Lower Cherokee (Eng. Lower Cherokee), whose area was closest to South Carolina, tended to support the war. Some took part in the Catawba attacks on the colonists' settlements on the Santee River . The Overhill Cherokee , whose tribal area was furthest from South Carolina, wanted more of an alliance with South Carolina and a war against the Creek. One of the village chiefs who strongly promoted the idea of allying themselves with South Carolina was Caesar of the Middle Cherokee (Eng. Middle or Central Cherokee).

In late 1715, two South Carolina traders visited the Cherokee and returned to Charles Town with a large Cherokee delegation. An alliance was formed and plans for a war on the Creek developed. In the following month, however, the Cherokee failed to unite with the troops of South Carolina as planned in Savannah Town . South Carolina then sent an expedition with over 300 soldiers to the Cherokee, which arrived in December 1715. They split up and visited the main settlements of the Lower, Middle and Upper Cherokee and quickly realized how divided the Cherokee were. During the winter, the chief Caesar traveled through the various settlements of the people, trying to find supporters for a war against the Creek. At the same time, other respected and influential chiefs urged caution and patience, including Charitey Hagey, whom the South Carolinians called "the Conjurer". Charitey Hagey came from the Cherokee village of Tugaloo , one of the Lower settlements near South Carolina. Many of these Cherokee were positive about peace with South Carolina, but were not ready to fight against tribes other than the Yuchi and Savannah River Shawnee.

The South Carolinians were told that the residents of the Lower Towns had sent an offer to negotiate, a "flag of truce", to the Creek and that a delegation from the Cherokee leaders had promised to come. Charitey Hagey and his supporters seemed to provide a neutral venue for the Creek-South Carolina peace negotiations, and they convinced South Carolina to abandon its plans for war. Instead, the South Carolinians spent the winter trying to convince Caesar and the war-voting Cherokee of peace.

Tugaloo massacre

On January 27, 1716, the South Carolinians were called to Tugaloo, where they found that the Creek delegation had arrived and 11 or 12 of them had been killed by the Cherokee. The Cherokee claimed the delegation was in fact a force of several hundred creeks and Yamasee who almost successfully ambushed South Carolina troops. It is unknown what actually happened in Tugaloo. That the Cherokee and Creek met in silence without South Carolina participating suggests that the Cherokee were still at odds as to whether to join the Creek to attack South Carolina or vice versa. It is conceivable that the Cherokee, as South Carolina's new trading partner, hoped to replace the Creek as South Carolina's main trading partner. Whatever factors ultimately led to the murders, they were likely preceded by a heated and unpredictable debate which, like the Pocotaligo massacre, resulted in an inevitable situation due to the murders. After the Tugaloo massacre, the only solution the Cherokee had left was to ally with South Carolina and wage war on the Creek.

The Cherokee-South Carolina alliance put an end to any plans for a major Creek invasion of South Carolina. At the same time, South Carolina sought peaceful relations with the Creek and refused to go to war with them. Although South Carolina provided the Cherokee with arms and trade goods, they did not give the Cherokee the military support that the war-voting Cherokee wanted. There were Cherokee victories in 1716 and 1717, but the Creek counterattacks undermined the Cherokee's initially divided will for an ongoing war. Still, the Creek and Cherokee carried out minor attacks on each other for generations.

In response to the Tugaloo massacre and the Cherokee attacks, the Ochese Creek took strategic defensive measures in the spring of 1716. They withdrew all of their villages from the Ocmulgee River basin to the Chattahoochee River . Originally the Ochese Creek had on Chattahoochee, but migrated to the Ocmulgee River and its tributary, Ochese Creek, from which they took their name, in 1690 to be closer to South Carolina. Her return to the Chattahoochee River in 1716 was less an escape than a restoration of the former conditions. The distance between the Chattahoochee and Charles Town protected the Indians from a possible attack on South Carolina.

In 1716 and 1717, after no major attack by Cherokee British forces, the Lower Creek found themselves in a position of expanded power and proceeded to raid their enemies, the British, the Catawba and the Cherokee. Without the South Carolina trade, however, they ran into serious shortages of weapons, ammunition, and gunpowder. On the other hand, the Cherokee were adequately supplied with English weapons by the British. The lure of trade with the British undermined anti-British voices among the Indians. In the spring of 1717 a couple of emissaries from Charles Town came to the Creek area and cautiously began to work towards peace.

At the same time, other Lower Creek were looking for ways to continue the war. In the fall of 1716, a group representing some of the Muskogee Creek nations traveled to the distant Iroquois Six Nations in New York State. Impressed by the Creek's diplomatic skills, the Iroquois sent 20 of their own ambassadors back to Carolina with the Creek. The Iroquois and the Creek were mostly interested in fighting their Indian enemies, such as the Catawba and Cherokee. For South Carolina, however, an alliance between the Iroquois and the Creek was something that had to be prevented at all costs. In response, South Carolina sent envoys to the Creek with a large shipment of merchandise as gifts.

Insecure borders

After the Yamasee and the Catawba withdrew, the South Carolina's militia recaptured abandoned settlements and tried to secure the border regions. They turned some of the houses on plantations into makeshift forts. The militia had done well in the offensively fought battles, but were unable to secure the borders against minor raids. Numerous members of the militia began to desert in the summer of 1715, some out of fear for their property and families, and others left South Carolina entirely.

In response to the militia failures, Governor Craven replaced them with a professional army. In August 1715, South Carolina's new army comprised about 600 citizens, 400 African American slaves, 170 friendly Indians, and 300 troops from North Carolina and Virginia. This marked the first time the South Carolina militia had been disbanded and replaced with a professional army. The high number of armed slaves whose owners were paid for this mission is remarkable.

But even this army was not able to secure the colony, the enemy Indians simply refused to fight on a battlefield and instead used guerrilla tactics such as ambushes or smaller raids. In addition, the Indians had such a large area that it was impossible to send an army against them. The army was therefore disbanded in the spring of 1716 after the alliance with the Cherokee.

End of war

After so many tribes were involved in the war, the participation of which changed and varied, there was no definable end to the war. According to some observers, the central crisis was over after a month or two. The colony's Lords Proprietors thought the colony was in danger for the first few weeks. Others call the alliance with the Cherokee the end of the conflict. Peace negotiations and treaties with various Creek and Muskoge tribes were concluded in late 1717. However, some tribes had never consented to the peace and were still under arms. The Yamasee and Apalachicola migrated south, but raided settlements in South Carolina well into the 1720s. Securing the borders remained problematic.

aftermath

Political changes in the colonies

Though it lasted for several years, the Yamasee War ultimately led to the overthrow of the Lords Proprietors by South Carolina. The residents of the Carolinas had already been dissatisfied with the system of property-owned colonies before the Yamasee War, and criticism of the system was finally intensified in the first phase of the war in 1715. The situation between the population and the Lords Proprietors visibly deteriorated in the years that followed. Around 1720 the conversion process from a colony owned by the Lords to a crown colony began . Nine years later, in 1729, North and South Carolina were officially declared crown colonies of the British Empire.

The war also led to the formation of the Georgia colony. Although other factors were also relevant to the establishment, the establishment of the colony would not have been possible without the withdrawal of the Yamasee. The few remaining tribesmen were known as Yamacraw . James Oglethorpe negotiated with the Yamacraw to get the land on which he would later build the capital of the new colony, Savannah .

Consequences for the Indian population

In the first year of the war, the Yamasee lost about a quarter of their population, either being killed or enslaved. The survivors moved south to the Altamaha River , in a region that had been their tribal territory in the 17th century. But it was not possible for them to live in safety there either and they became refugees. The people, which was ethnically mixed, split up as a result of the war. Over a third of the survivors chose to live by the Lower Creek and later likely became part of the emerging Creek Bund. Most of the Yamasee moved with the survivors of the Apalachicola to the vicinity of St. Augustine in Florida in the summer of 1715 . Despite many attempts to make peace, both by South Carolina individuals and the Yamasee tribe, the conflict between the two parties continued for decades. The Yamasee Spanish Florida were gradually decimated by disease and other factors, the survivors of the tribe later became part of the Seminoles .

The various Muskogee tribes that later formed the Creek Bund grew closer together after the Lake Yamasee War. The reoccupation of the Chattahoochee River by the Ochese Creek, who settled there together with the remains of the Apalachicola, Apalachee, Yamasee and others, seemed to represent a new Indian identity to the Europeans. According to the European view, this identity also needed a new name, the Spanish saw the union as a reincarnation of the Apalachicola Province of the 17th century, the British settlers usually called the group Lower Creek

The Catawba absorbed the remnants of the northern tribes of the Piedmont , for example the Cheraw, Congaree, Santee , Pee Dee, Waxhaw, Wateree, Waccamaw and Winyah , even if these tribes remained largely independent for some time and were initially able to maintain their cultural identity. The Catawba League emerged from the war as the most powerful Indian force in the Piedmont, and this was reinforced when the Tuscarora moved north to join the Iroquois. A year after the peace treaty with South Carolina in 1716, some Santee and Waxhaw killed several colonists. In response, South Carolina asked the Catawba to attack the two tribes and take them out, which the Catawba did. Survivors Santee and Waxhaw were integrated into their society by the Catawba either as slaves or as "adopted children". The Cheraw tribe remained hostile for years.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Steven J. Oatis: A Colonial Complex: South Carolina's Frontiers in the Era of the Yamasee War, 1680-1730. , University of Nebraska Press 2004, ISBN 0-8032-3575-5 . Page 167.

- ^ William L. Ramsey: The Yamasee War: A Study of Culture, Economy, and Conflict in the Colonial South. University of Nebraska Press, 2008, Part I: "Tinder," pages 13 through 56, ISBN 0-8032-3972-6

- ^ William L. Ramsey: The Yamasee War: A Study of Culture, Economy, and Conflict in the Colonial South. University of Nebraska Press, 2008, Gender Section, pages 15-20 , ISBN 0-8032-3972-6

- ^ A b Alan Gallay: The Indian Slave Trade: The Rise of the English Empire in the American South, 1670-1717. Yale University Press, 2002, pages 267-268 and 283, ISBN 0-300-08754-3

- ↑ John Worth: Prelude to Abandonment: The Interior Provinces of Early 17th-Century Georgia. In: Early Georgia: Journal of the Society for Georgia Archeology, Issue 21/1993, pages 40-45

- ↑ National Register Multiple Property Submission, Dr. Chester B. DePratter: The Foundation, Occupation, and Abandonment of Yamasee Indian Towns in the South Carolina Lowcountry, 1684-1715 (PDF; 592 kB). For more information , see John Reed Swanton: The Indian Tribes of North America , Genealogical Publishing Company, 2003, pages 114-116 , ISBN 0-8063-1730-2

- ↑ Steven J. Oatis: A Colonial Complex: South Carolina's Frontiers in the Era of the Yamasee War, 1680-1730. University of Nebraska Press, 2004 page 59, ISBN 0-8032-3575-5

- ↑ a b c Oatis, A Colonial Complex , 124-125.

- ^ A b Lawrence Sanders Rowland, Alexander Moore, George C. Rogers: The History of Beaufort County, South Carolina: 1514-1861. , University of South Carolina Press, 1996, ISBN 1-57003-090-1 . Pages 95-96

- ^ According to Rowland, Moore, Rogers in The History of Beaufort County, South Carolina: 1514-1861 Burrough was shot in the lung and another bullet struck his cheek and destroyed most of his teeth. (Page 96)

- ^ A b c d Rowland, Moore, Rogers: The History of Beaufort County, South Carolina: 1514-1861. , 96 ff.

- ^ Oatis, A Colonial Complex, 145.

- ^ Oatis, A Colonial Complex , 165-166.

- ↑ Oatis, A Colonial Complex , 288-291.

literature

- Alan Gallay: The Indian Slave Trade: The Rise of the English Empire in the American South 1670-1717. Yale University Press, 2002, ISBN 0-300-10193-7

- Steven J. Oatis: A Colonial Complex: South Carolina's Frontiers in the Era of the Yamasee War, 1680-1730. University of Nebraska Press, 2004, ISBN 0-8032-3575-5

- Early Georgia: Journal of the Society for Georgia Archeology, Issue 21/1993, pages 24-58: "John Worth: Prelude to Abandonment: The Interior Provinces of Early 17th-Century Georgia. "

further reading

- Verner Crane: The Southern Frontier, 1670-1732. Duke University Press, 1928

Web links

- History Cooperative, The Journal of American History: "William L. Ramsey, " Something Cloudy in Their Looks: The Origins of the Yamasee War Reconsidered "

- Our Georgia History: Yamassee War of 1715

- South Carolina Forts ( August 31, 2005 memento on the Internet Archive ); Yamasee War era forts include Willtown Fort, Passage Fort, Saltcatchers Fort, Fort Moore, and Benjamin Schenckingh's Fort.

- Appalachian Summit, Chapter 4: Dear Skins Furrs and Younge Indian Slaves ( August 17, 2011 memento in the Internet Archive ), transcriptions of primary source letters regarding the Cherokee during the Yamasee War era.