Corticosteroid: Difference between revisions

Adding local short description: "Class of steroid hormones", overriding Wikidata description "class of steroid hormones, including both natural and artificial compounds" (Shortdesc helper) |

HeyElliott (talk | contribs) |

||

| (45 intermediate revisions by 31 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|Class of steroid hormones}} |

{{Short description|Class of steroid hormones}} |

||

{{expert needed|medicine|date=January 2018}} |

|||

{{Infobox drug class |

{{Infobox drug class |

||

| Image = {{wikidata|property|raw|Q190875|P117}} |

| Image = {{wikidata|property|raw|Q190875|P117}} |

||

| Alt = |

| Alt = |

||

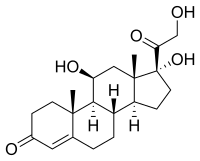

| Caption = [[Cortisol]] ([[hydrocortisone]]), a corticosteroid with both [[glucocorticoid]] and [[mineralocorticoid]] activity and effects. |

| Caption = [[Cortisol]] ([[hydrocortisone]]), a corticosteroid with both [[glucocorticoid]] and [[mineralocorticoid]] activity and effects. |

||

| Width = 250px |

| Width = 250px |

||

| Line 13: | Line 12: | ||

| Chemical_class = [[Steroid]]s |

| Chemical_class = [[Steroid]]s |

||

<!-- Clinical data --> |

<!-- Clinical data --> |

||

| Drugs.com = |

| Drugs.com = |

||

| Consumer_Reports = |

| Consumer_Reports = |

||

| medicinenet = |

| medicinenet = |

||

| rxlist = |

| rxlist = |

||

<!-- External links --> |

<!-- External links --> |

||

| MeshID = |

| MeshID = |

||

}} |

}} |

||

| ⚫ | '''Corticosteroids''' are a class of [[steroid hormone]]s that are produced in the [[adrenal cortex]] of [[vertebrates]], as well as the synthetic analogues of these hormones. Two main classes of corticosteroids, [[glucocorticoid]]s and [[mineralocorticoid]]s, are involved in a wide range of [[physiology|physiological]] processes, including [[stress (medicine)|stress response]], [[immune system|immune response]], and regulation of [[inflammation]], [[carbohydrate]] [[metabolism]], [[protein]] [[catabolism]], blood [[electrolyte]] levels, and behavior.<ref name=NusseySaffron2001>{{Cite book|title = Endocrinology: An Integrated Approach| vauthors = Nussey S, Whitehead S |publisher = Oxford: BIOS Scientific Publishers|year = 2001|url = https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK26/.| chapter=The adrenal gland }}</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | Some common naturally occurring steroid hormones are [[cortisol]] ({{chem|C|21|H|30|O|5}}), [[corticosterone]] ({{chem|C|21|H|30|O|4}}), [[cortisone]] ({{chem|C|21|H|28|O|5}}) and [[aldosterone]] ({{chem|C|21|H|28|O|5}}) (cortisone and [[aldosterone]] are [[isomers]]). The main corticosteroids produced by the adrenal cortex are cortisol and aldosterone.<ref name=NusseySaffron2001 /> |

||

| ⚫ | '''Corticosteroids''' are a class of [[steroid hormone]]s that are produced in the [[adrenal cortex]] of [[vertebrates]], as well as the synthetic analogues of these hormones. Two main classes of corticosteroids, [[glucocorticoid]]s and [[mineralocorticoid]]s, are involved in a wide range of [[physiology|physiological]] processes, including [[stress (medicine)|stress response]], [[immune system|immune response]], and regulation of [[inflammation]], [[carbohydrate]] [[metabolism]], [[protein]] [[catabolism]], blood [[electrolyte]] levels, and behavior.<ref name= |

||

| ⚫ | Some common naturally occurring steroid hormones are [[cortisol]] ({{chem|C|21|H|30|O|5}}), [[corticosterone]] ({{chem|C|21|H|30|O|4}}), [[cortisone]] ({{chem|C|21|H|28|O|5}}) and [[aldosterone]] ({{chem|C|21|H|28|O|5}}) |

||

{{TOC limit|3}} |

{{TOC limit|3}} |

||

| Line 31: | Line 30: | ||

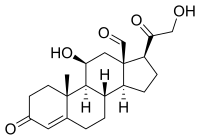

[[Image:{{wikidata|property|raw|Q422543|P117}}|thumb|200px|[[Corticosterone]]]] |

[[Image:{{wikidata|property|raw|Q422543|P117}}|thumb|200px|[[Corticosterone]]]] |

||

[[Image:{{wikidata|property|raw|Q184564|P117}}|thumb|200px|[[Aldosterone]]]] |

[[Image:{{wikidata|property|raw|Q184564|P117}}|thumb|200px|[[Aldosterone]]]] |

||

| ⚫ | * '''[[Glucocorticoid]]s''' such as [[cortisol]] affect carbohydrate, fat, and protein metabolism, and have [[anti-inflammatory]], [[Immunosuppression|immunosuppressive]], [[Chemotherapy|anti-proliferative]], and [[Vasoconstriction|vasoconstrictive]] effects.<ref name=":1">{{cite journal | vauthors = Liu D, Ahmet A, Ward L, Krishnamoorthy P, Mandelcorn ED, Leigh R, Brown JP, Cohen A, Kim H | display-authors = 6 | title = A practical guide to the monitoring and management of the complications of systemic corticosteroid therapy | journal = Allergy, Asthma, and Clinical Immunology | volume = 9 | issue = 1 | pages = 30 | date = August 2013 | pmid = 23947590 | pmc = 3765115 | doi = 10.1186/1710-1492-9-30 | doi-access = free }}</ref> Anti-inflammatory effects are mediated by blocking the action of [[Inflammation|inflammatory mediators]] ([[transrepression]]) and inducing anti-inflammatory mediators ([[transactivation]]).<ref name=":1" /> Immunosuppressive effects are mediated by suppressing [[Type IV hypersensitivity|delayed hypersensitivity reactions]] by direct action on [[T cell|T-lymphocytes]].<ref name=":1" /> Anti-proliferative effects are mediated by inhibition of [[DNA synthesis]] and [[Epidermis|epidermal cell]] turnover.<ref name=":1" /> [[Vasoconstriction|Vasoconstrictive]] effects are mediated by inhibiting the action of inflammatory mediators such as [[histamine]].<ref name=":1" /> |

||

| ⚫ | * '''[[Glucocorticoid]]s''' such as [[cortisol]] affect carbohydrate, fat, and protein metabolism, and have [[anti-inflammatory]], [[Immunosuppression|immunosuppressive]], [[Chemotherapy|anti-proliferative]], and [[Vasoconstriction|vasoconstrictive]] effects.<ref name=":1">{{ |

||

* '''[[Mineralocorticoid]]s''' such as [[aldosterone]] are primarily involved in the regulation of [[Water-electrolyte balance|electrolyte]] and water balance by modulating [[Ion transporter|ion transport]] in the [[Epithelium|epithelial cells]] of the [[Nephron|renal tubules]] of the [[kidney]].<ref name=":1" /> |

* '''[[Mineralocorticoid]]s''' such as [[aldosterone]] are primarily involved in the regulation of [[Water-electrolyte balance|electrolyte]] and water balance by modulating [[Ion transporter|ion transport]] in the [[Epithelium|epithelial cells]] of the [[Nephron|renal tubules]] of the [[kidney]].<ref name=":1" /> |

||

==Medical uses== |

==Medical uses== |

||

Synthetic [[pharmaceutical drug]]s with corticosteroid-like effects are used in a variety of conditions, ranging from [[brain tumor]]s |

Synthetic [[pharmaceutical drug]]s with corticosteroid-like effects are used in a variety of conditions, ranging from [[Hematological cancer|hematological neoplasms]]<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Faggiano A, Mazzilli R, Natalicchio A, Adinolfi V, Argentiero A, Danesi R, D'Oronzo S, Fogli S, Gallo M, Giuffrida D, Gori S, Montagnani M, Ragni A, Renzelli V, Russo A, Silvestris N, Franchina T, Tuveri E, Cinieri S, Colao A, Giorgino F, Zatelli MC | display-authors = 6 | title = Corticosteroids in oncology: Use, overuse, indications, contraindications. An Italian Association of Medical Oncology (AIOM)/ Italian Association of Medical Diabetologists (AMD)/ Italian Society of Endocrinology (SIE)/ Italian Society of Pharmacology (SIF) multidisciplinary consensus position paper | journal = Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology | volume = 180 | pages = 103826 | date = December 2022 | pmid = 36191821 | doi = 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2022.103826 | hdl-access = free | s2cid = 252663155 | hdl = 10447/582211 }}</ref> to [[brain tumor]]s or [[skin disease]]s. [[Dexamethasone]] and its derivatives are almost pure glucocorticoids, while [[prednisone]] and its derivatives have some mineralocorticoid action in addition to the glucocorticoid effect. [[Fludrocortisone]] (Florinef) is a synthetic mineralocorticoid. [[Hydrocortisone]] (cortisol) is typically used for replacement therapy, ''e.g.'' for [[adrenal insufficiency]] and [[congenital adrenal hyperplasia]]. |

||

Medical conditions treated with systemic corticosteroids:<ref name=":1" /><ref>{{ |

Medical conditions treated with systemic corticosteroids:<ref name=":1" /><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Mohamadi A, Chan JJ, Claessen FM, Ring D, Chen NC | title = Corticosteroid Injections Give Small and Transient Pain Relief in Rotator Cuff Tendinosis: A Meta-analysis | journal = Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research | volume = 475 | issue = 1 | pages = 232–243 | date = January 2017 | pmid = 27469590 | pmc = 5174041 | doi = 10.1007/s11999-016-5002-1 }}</ref> |

||

{{div col|colwidth=30em}} |

{{div col|colwidth=30em}} |

||

| Line 73: | Line 71: | ||

** [[Hemolytic anemia]] |

** [[Hemolytic anemia]] |

||

** [[Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura]] |

** [[Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura]] |

||

**[[Multiple Myeloma]] |

** [[Multiple Myeloma]] |

||

* [[Rheumatology]]/[[Immunology]] |

* [[Rheumatology]]/[[Immunology]] |

||

** [[Rheumatoid arthritis]] |

** [[Rheumatoid arthritis]] |

||

** [[Systemic lupus erythematosus]] |

** [[Systemic lupus erythematosus]] |

||

** [[Polymyalgia rheumatica]] |

** [[Polymyalgia rheumatica]] |

||

| Line 98: | Line 96: | ||

{{div col end}} |

{{div col end}} |

||

Topical formulations are also available for the [[skin disease|skin]], eyes ([[uveitis]]), lungs ([[asthma]]), nose ([[rhinitis]]), |

Topical formulations are also available for the [[skin disease|skin]], eyes ([[uveitis]]), lungs ([[asthma]]), nose ([[rhinitis]]), and [[inflammatory bowel disease|bowels]]. Corticosteroids are also used supportively to prevent nausea, often in combination with 5-HT<sub>3</sub> antagonists (e.g., [[ondansetron]]). |

||

Typical [[adverse drug reaction|undesired effects]] of glucocorticoids present quite uniformly as drug-induced [[Cushing's syndrome]]. Typical mineralocorticoid side-effects are [[arterial hypertension|hypertension]] (abnormally high blood pressure), steroid induced diabetes mellitus, psychosis, poor sleep, [[hypokalemia]] (low potassium levels in the blood), [[hypernatremia]] (high sodium levels in the blood) without causing [[peripheral edema]], [[metabolic alkalosis]] and connective tissue weakness.<ref>{{cite book| |

Typical [[adverse drug reaction|undesired effects]] of glucocorticoids present quite uniformly as drug-induced [[Cushing's syndrome]]. Typical mineralocorticoid side-effects are [[arterial hypertension|hypertension]] (abnormally high blood pressure), steroid induced diabetes mellitus, psychosis, poor sleep, [[hypokalemia]] (low potassium levels in the blood), [[hypernatremia]] (high sodium levels in the blood) without causing [[peripheral edema]], [[metabolic alkalosis]] and connective tissue weakness.<ref>{{cite book| vauthors = Werner R |title=A massage therapist's guide to Pathology |publisher=Lippincott Williams & Wilkins |location=Pennsylvania |year=2005 |edition=3rd }}</ref> Wound healing or ulcer formation may be inhibited by the immunosuppressive effects. |

||

| ⚫ | A variety of steroid medications, from anti-allergy nasal sprays ([[Nasonex]], [[Flonase]]) to topical skin creams, to eye drops ([[Tobradex]]), to prednisone have been implicated in the development of [[central serous retinopathy]] (CSR).<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Carvalho-Recchia CA, Yannuzzi LA, Negrão S, Spaide RF, Freund KB, Rodriguez-Coleman H, Lenharo M, Iida T | display-authors = 6 | title = Corticosteroids and central serous chorioretinopathy | journal = Ophthalmology | volume = 109 | issue = 10 | pages = 1834–1837 | date = October 2002 | pmid = 12359603 | doi = 10.1016/S0161-6420(02)01117-X }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://buteykola.com/2010/07/the-new-york-times-a-breathing-technique-offers-help-for-people-with-asthma |title=The New York Times :: A Breathing Technique Offers Help for People With Asthma |publisher=buteykola.com |access-date=2012-11-30 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120724105056/http://buteykola.com/2010/07/the-new-york-times-a-breathing-technique-offers-help-for-people-with-asthma/ |archive-date=2012-07-24 |url-status=dead }}</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | Clinical and experimental evidence indicates that corticosteroids can cause permanent eye damage by inducing |

||

| ⚫ | Corticosteroids have been widely used in treating people with [[traumatic brain injury]].<ref>{{cite book|title=Corticosteroids for acute traumatic brain injury|vauthors=Alderson P, Roberts I |publisher=The Cochrane Collaboration|chapter=Plain Language Summary|page=2}}</ref> A [[systematic review]] identified 20 randomised controlled trials and included 12,303 participants, then compared patients who received corticosteroids with patients who received no treatment. The authors recommended people with traumatic head injury should not be routinely treated with corticosteroids.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Alderson P, Roberts I | title = Corticosteroids for acute traumatic brain injury | journal = The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews | volume = 2005 | issue = 1 | pages = CD000196 | date = January 2005 | pmid = 15674869 | pmc = 7043302 | doi = 10.1002/14651858.CD000196.pub2 | veditors = Alderson P }}</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | A variety of steroid medications, from anti-allergy nasal sprays ([[Nasonex]], [[Flonase]]) to topical skin creams, to eye drops ([[Tobradex]]), to prednisone have been implicated in the development of CSR.<ref>{{cite journal| |

||

| ⚫ | Corticosteroids have been widely used in treating people with [[traumatic brain injury]].<ref>{{cite book|title=Corticosteroids for acute traumatic brain injury|vauthors=Alderson P, Roberts I |publisher=The Cochrane Collaboration|chapter=Plain Language Summary|page=2}}</ref> A [[systematic review]] identified 20 randomised controlled trials and included 12,303 participants, then compared patients who received corticosteroids with patients who received no treatment. The authors recommended people with traumatic head injury should not be routinely treated with corticosteroids.<ref>{{ |

||

==Pharmacology== |

==Pharmacology== |

||

Corticosteroids act as [[agonist]]s of the [[glucocorticoid receptor]] and/or the [[mineralocorticoid receptor]]. |

Corticosteroids act as [[agonist]]s of the [[glucocorticoid receptor]] and/or the [[mineralocorticoid receptor]]. |

||

In addition to their corticosteroid activity, some corticosteroids may have some [[progestogen (medication)|progestogen]]ic activity and may produce sex-related side effects.<ref name="pmid10518812">{{cite journal | vauthors = Lumry WR | title = A review of the preclinical and clinical data of newer intranasal steroids used in the treatment of allergic rhinitis | journal = |

In addition to their corticosteroid activity, some corticosteroids may have some [[progestogen (medication)|progestogen]]ic activity and may produce sex-related side effects.<ref name="pmid10518812">{{cite journal | vauthors = Lumry WR | title = A review of the preclinical and clinical data of newer intranasal steroids used in the treatment of allergic rhinitis | journal = The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology | volume = 104 | issue = 4 Pt 1 | pages = S150–S158 | date = October 1999 | pmid = 10518812 | doi = 10.1016/s0091-6749(99)70311-8 }}</ref><ref name="pmid27874912">{{cite journal | vauthors = Brook EM, Hu CH, Kingston KA, Matzkin EG | title = Corticosteroid Injections: A Review of Sex-Related Side Effects | journal = Orthopedics | volume = 40 | issue = 2 | pages = e211–e215 | date = March 2017 | pmid = 27874912 | doi = 10.3928/01477447-20161116-07 }}</ref><ref name="pmid7121132">{{cite journal | vauthors = Luzzani F, Gallico L, Glässer A | title = In vitro and ex vivo binding to uterine progestin receptors of the rat as a tool to assay progestational activity of glucocorticoids | journal = Methods and Findings in Experimental and Clinical Pharmacology | volume = 4 | issue = 4 | pages = 237–242 | date = 1982 | pmid = 7121132 }}</ref><ref name="pmid376542">{{cite journal | vauthors = Cunningham GR, Goldzieher JW, de la Pena A, Oliver M | title = The mechanism of ovulation inhibition by triamcinolone acetonide | journal = The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism | volume = 46 | issue = 1 | pages = 8–14 | date = January 1978 | pmid = 376542 | doi = 10.1210/jcem-46-1-8 }}</ref> |

||

== |

==Pharmacogenetics== |

||

===Asthma=== |

===Asthma=== |

||

Patients' response to inhaled corticosteroids has some basis in genetic variations. Two genes of interest are CHRH1 ([[corticotropin-releasing hormone receptor 1]]) and TBX21 ([[transcription factor T-bet]]). Both genes display some degree of polymorphic variation in humans, which may explain how some patients respond better to inhaled corticosteroid therapy than others.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Tantisira KG, Lake S, Silverman ES, Palmer LJ, Lazarus R, Silverman EK, Liggett SB, Gelfand EW, Rosenwasser LJ, Richter B, Israel E, Wechsler M, Gabriel S, Altshuler D, Lander E, Drazen J, Weiss ST| title = Corticosteroid pharmacogenetics: association of sequence variants in CRHR1 with improved lung function in asthmatics treated with inhaled corticosteroids | journal = Human Molecular Genetics | volume = 13 | issue = 13 | pages = |

Patients' response to inhaled corticosteroids has some basis in genetic variations. Two genes of interest are CHRH1 ([[corticotropin-releasing hormone receptor 1]]) and TBX21 ([[transcription factor T-bet]]). Both genes display some degree of polymorphic variation in humans, which may explain how some patients respond better to inhaled corticosteroid therapy than others.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Tantisira KG, Lake S, Silverman ES, Palmer LJ, Lazarus R, Silverman EK, Liggett SB, Gelfand EW, Rosenwasser LJ, Richter B, Israel E, Wechsler M, Gabriel S, Altshuler D, Lander E, Drazen J, Weiss ST | display-authors = 6 | title = Corticosteroid pharmacogenetics: association of sequence variants in CRHR1 with improved lung function in asthmatics treated with inhaled corticosteroids | journal = Human Molecular Genetics | volume = 13 | issue = 13 | pages = 1353–1359 | date = July 2004 | pmid = 15128701 | doi = 10.1093/hmg/ddh149 | doi-access = free }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Tantisira KG, Hwang ES, Raby BA, Silverman ES, Lake SL, Richter BG, Peng SL, Drazen JM, Glimcher LH, Weiss ST | display-authors = 6 | title = TBX21: a functional variant predicts improvement in asthma with the use of inhaled corticosteroids | journal = Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America | volume = 101 | issue = 52 | pages = 18099–18104 | date = December 2004 | pmid = 15604153 | pmc = 539815 | doi = 10.1073/pnas.0408532102 | doi-access = free | bibcode = 2004PNAS..10118099T }}</ref> However, not all asthma patients respond to corticosteroids and large sub groups of asthma patients are corticosteroid resistant.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Peters MC, Kerr S, Dunican EM, Woodruff PG, Fajt ML, Levy BD, Israel E, Phillips BR, Mauger DT, Comhair SA, Erzurum SC, Johansson MW, Jarjour NN, Coverstone AM, Castro M, Hastie AT, Bleecker ER, Wenzel SE, Fahy JV | display-authors = 6 | title = Refractory airway type 2 inflammation in a large subgroup of asthmatic patients treated with inhaled corticosteroids | journal = The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology | volume = 143 | issue = 1 | pages = 104–113.e14 | date = January 2019 | pmid = 29524537 | pmc = 6128784 | doi = 10.1016/j.jaci.2017.12.1009 }}</ref> |

||

A study funded by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute of children and teens with mild persistent asthma found that using the control inhaler as needed worked the same as daily use in improving asthma control, number of asthma flares, how well the lungs work, and quality of life. Children and teens using the inhaler as needed used about one-fourth the amount of corticosteroid medicine as children and teens using it daily.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Sumino K, Bacharier LB, Taylor J, Chadwick-Mansker K, Curtis V, Nash A, Jackson-Triggs S, Moen J, Schechtman KB, Garbutt J, Castro M | display-authors = 6 | title = A Pragmatic Trial of Symptom-Based Inhaled Corticosteroid Use in African-American Children with Mild Asthma | language = English | journal = The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. In Practice | volume = 8 | issue = 1 | pages = 176–185.e2 | date = January 2020 | pmid = 31371165 | doi = 10.1016/j.jaip.2019.06.030 | s2cid = 199380330 }}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |date=2021-08-13 |title=Managing Mild Asthma in Children Age Six and Older |url=https://www.pcori.org/evidence-updates/managing-mild-asthma-children-age-six-and-older |access-date=2022-05-10 |website=Managing Mild Asthma in Children Age Six and Older {{!}} PCORI |language=en}}</ref> |

|||

==Adverse effects== |

==Adverse effects== |

||

| Line 123: | Line 120: | ||

Use of corticosteroids has numerous side-effects, some of which may be severe: |

Use of corticosteroids has numerous side-effects, some of which may be severe: |

||

| ⚫ | * Severe [[amoebic colitis]]: [[Fulminant]] amoebic colitis is associated with high case fatality and can occur in patients infected with the parasite ''[[Entamoeba histolytica]]'' after exposure to corticosteroid medications.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Shirley DA, Moonah S | title = Fulminant Amebic Colitis after Corticosteroid Therapy: A Systematic Review | journal = PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases | volume = 10 | issue = 7 | pages = e0004879 | date = July 2016 | pmid = 27467600 | pmc = 4965027 | doi = 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004879 | doi-access = free }}</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | * Neuropsychiatric<!-- Anabolic steroids are entirely different from corticosteroids -->: [[steroid psychosis]],<ref name="Psychiatric Adverse Drug Reactions: Steroid Psychosis">{{cite web| vauthors = Hall R |title=Psychiatric Adverse Drug Reactions: Steroid Psychosis|url=http://www.drrichardhall.com/steroid.htm|publisher=Director of Research Monarch Health Corporation Marblehead, Massachusetts|access-date=2013-06-23|archive-date=2013-07-17|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130717083547/http://www.drrichardhall.com/steroid.htm|url-status=dead}}</ref> and [[anxiety (mood)|anxiety]],<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Korte SM | title = Corticosteroids in relation to fear, anxiety and psychopathology | journal = Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews | volume = 25 | issue = 2 | pages = 117–142 | date = March 2001 | pmid = 11323078 | doi = 10.1016/S0149-7634(01)00002-1 | s2cid = 8904351 }}</ref> [[depression (mood)|depression]]. Therapeutic doses may cause a feeling of artificial well-being ("steroid euphoria").<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Swinburn CR, Wakefield JM, Newman SP, Jones PW | title = Evidence of prednisolone induced mood change ('steroid euphoria') in patients with chronic obstructive airways disease | journal = British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology | volume = 26 | issue = 6 | pages = 709–713 | date = December 1988 | pmid = 3242575 | pmc = 1386585 | doi = 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1988.tb05309.x }}</ref> The neuropsychiatric effects are partly mediated by sensitization of the body to the actions of adrenaline. Therapeutically, the bulk of corticosteroid dose is given in the morning to mimic the body's diurnal rhythm; if given at night, the feeling of being energized will interfere with sleep. An extensive review is provided by Flores and Gumina.<ref>Benjamin H. Flores and Heather Kenna Gumina. The Neuropsychiatric Sequelae of Steroid Treatment. URL:http://www.dianafoundation.com/articles/df_04_article_01_steroids_pg01.html</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | * Severe |

||

| ⚫ | * Neuropsychiatric<!-- Anabolic steroids are entirely different from corticosteroids -->: [[steroid psychosis]],<ref name="Psychiatric Adverse Drug Reactions: Steroid Psychosis">{{cite web| |

||

* Cardiovascular: Corticosteroids can cause sodium retention through a direct action on the kidney, in a manner analogous to the mineralocorticoid [[aldosterone]]. This can result in fluid retention and [[hypertension]]. |

* Cardiovascular: Corticosteroids can cause sodium retention through a direct action on the kidney, in a manner analogous to the mineralocorticoid [[aldosterone]]. This can result in fluid retention and [[hypertension]]. |

||

* Metabolic: Corticosteroids cause a movement of body fat to the face and torso, resulting in "[[moon face]]", "buffalo hump", and "pot belly" or "beer belly", and cause movement of body fat away from the limbs. This has been termed [[corticosteroid-induced lipodystrophy]]. Due to the diversion of amino-acids to glucose, they are considered anti-anabolic, and long term therapy can cause muscle wasting.<ref>{{cite journal | |

* Metabolic: Corticosteroids cause a movement of body fat to the face and torso, resulting in "[[moon face]]", "buffalo hump", and "pot belly" or "beer belly", and cause movement of body fat away from the limbs. This has been termed [[corticosteroid-induced lipodystrophy]]. Due to the diversion of amino-acids to glucose, they are considered anti-anabolic, and long term therapy can cause muscle wasting (muscle atrophy).<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Hasselgren PO, Alamdari N, Aversa Z, Gonnella P, Smith IJ, Tizio S | title = Corticosteroids and muscle wasting: role of transcription factors, nuclear cofactors, and hyperacetylation | journal = Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition and Metabolic Care | volume = 13 | issue = 4 | pages = 423–428 | date = July 2010 | pmid = 20473154 | pmc = 2911625 | doi = 10.1097/MCO.0b013e32833a5107 }}</ref> Besides muscle atrophy, steroid myopathy includes muscle pains (myalgias), muscle weakness (typically of the proximal muscles), serum creatine kinase normal, EMG myopathic, and some have type II (fast-twitch/glycolytic) fibre atrophy.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Rodolico C, Bonanno C, Pugliese A, Nicocia G, Benvenga S, Toscano A | title = Endocrine myopathies: clinical and histopathological features of the major forms | journal = Acta Myologica | volume = 39 | issue = 3 | pages = 130–135 | date = September 2020 | pmid = 33305169 | pmc = 7711326 | doi = 10.36185/2532-1900-017 }}</ref> |

||

* Endocrine: By increasing the production of glucose from amino-acid breakdown and opposing the action of insulin, corticosteroids can cause [[hyperglycemia]],<ref>{{ |

* Endocrine: By increasing the production of glucose from amino-acid breakdown and opposing the action of insulin, corticosteroids can cause [[hyperglycemia]],<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Donihi AC, Raval D, Saul M, Korytkowski MT, DeVita MA | title = Prevalence and predictors of corticosteroid-related hyperglycemia in hospitalized patients | journal = Endocrine Practice | volume = 12 | issue = 4 | pages = 358–362 | year = 2006 | pmid = 16901792 | doi = 10.4158/ep.12.4.358 }}</ref> [[insulin resistance]] and [[diabetes mellitus]].<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Blackburn D, Hux J, Mamdani M | title = Quantification of the Risk of Corticosteroid-induced Diabetes Mellitus Among the Elderly | journal = Journal of General Internal Medicine | volume = 17 | issue = 9 | pages = 717–720 | date = September 2002 | pmid = 12220369 | pmc = 1495107 | doi = 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10649.x }}</ref> |

||

* Skeletal: [[Steroid-induced osteoporosis]] may be a side-effect of long-term corticosteroid use.<ref>{{ |

* Skeletal: [[Steroid-induced osteoporosis]] may be a side-effect of long-term corticosteroid use.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Chalitsios CV, Shaw DE, McKeever TM | title = Risk of osteoporosis and fragility fractures in asthma due to oral and inhaled corticosteroids: two population-based nested case-control studies | journal = Thorax | volume = 76 | issue = 1 | pages = 21–28 | date = January 2021 | pmid = 33087546 | doi = 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2020-215664 | s2cid = 224822416 | url = https://nottingham-repository.worktribe.com/output/4983605 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Chalitsios CV, McKeever TM, Shaw DE | title = Incidence of osteoporosis and fragility fractures in asthma: a UK population-based matched cohort study | journal = The European Respiratory Journal | volume = 57 | issue = 1 | date = January 2021 | pmid = 32764111 | doi = 10.1183/13993003.01251-2020 | s2cid = 221078530 | doi-access = free }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Chalitsios CV, Shaw DE, McKeever TM | title = Corticosteroids and bone health in people with asthma: A systematic review and meta-analysis | journal = Respiratory Medicine | volume = 181 | pages = 106374 | date = May 2021 | pmid = 33799052 | doi = 10.1016/j.rmed.2021.106374 | s2cid = 232771681 | doi-access = free }}</ref> Use of inhaled corticosteroids among children with asthma may result in decreased height.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Zhang L, Prietsch SO, Ducharme FM | title = Inhaled corticosteroids in children with persistent asthma: effects on growth | journal = The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews | volume = 2014 | issue = 7 | pages = CD009471 | date = July 2014 | pmid = 25030198 | pmc = 8407362 | doi = 10.1002/14651858.CD009471.pub2 | doi-access = free }}</ref> |

||

* Gastro-intestinal: While cases of [[colitis]] have been reported, corticosteroids are often prescribed when the colitis, although due to suppression of the immune response to pathogens, should be considered only after ruling out infection or microbe/fungal overgrowth in the gastrointestinal tract. While the evidence for corticosteroids causing [[peptic ulcer]]ation is relatively poor except for high doses taken for over a month,<ref name="pmid8826575">{{ |

* Gastro-intestinal: While cases of [[colitis]] have been reported, corticosteroids are often prescribed when the colitis, although due to suppression of the immune response to pathogens, should be considered only after ruling out infection or microbe/fungal overgrowth in the gastrointestinal tract. While the evidence for corticosteroids causing [[peptic ulcer]]ation is relatively poor except for high doses taken for over a month,<ref name="pmid8826575">{{cite journal | vauthors = Pecora PG, Kaplan B | title = Corticosteroids and ulcers: is there an association? | journal = The Annals of Pharmacotherapy | volume = 30 | issue = 7–8 | pages = 870–872 | year = 1996 | pmid = 8826575 | doi = 10.1177/106002809603000729 | s2cid = 13594804 }}</ref> the majority of doctors {{as of|lc=y|2010}} still believe this is the case, and would consider protective prophylactic measures.<ref name="pmid20569095">{{cite journal | vauthors = Martínek J, Hlavova K, Zavada F, Seifert B, Rejchrt S, Urban O, Zavoral M | title = "A surviving myth"--corticosteroids are still considered ulcerogenic by a majority of physicians | journal = Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology | volume = 45 | issue = 10 | pages = 1156–1161 | date = October 2010 | pmid = 20569095 | doi = 10.3109/00365521.2010.497935 | s2cid = 5140517 }}</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | * Eyes: chronic use may predispose to [[cataract]] and [[glaucoma]]. Clinical and experimental evidence indicates that corticosteroids can cause permanent eye damage by inducing central serous retinopathy (CSR, also known as central serous chorioretinopathy, CSC).<ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Abouammoh MA |date=2015 |title=Advances in the treatment of central serous chorioretinopathy |journal=Saudi Journal of Ophthalmology |volume=29 |issue=4 |pages=278–286 |doi=10.1016/j.sjopt.2015.01.007 |pmc=4625218 |pmid=26586979}}</ref> This should be borne in mind when treating patients with [[optic neuritis]]. There is experimental and clinical evidence that, at least in [[optic neuritis]] speed of treatment initiation is important.<ref>{{cite journal |display-authors=6 |vauthors=Petzold A, Braithwaite T, van Oosten BW, Balk L, Martinez-Lapiscina EH, Wheeler R, Wiegerinck N, Waters C, Plant GT |date=January 2020 |title=Case for a new corticosteroid treatment trial in optic neuritis: review of updated evidence |journal=Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry |volume=91 |issue=1 |pages=9–14 |doi=10.1136/jnnp-2019-321653 |pmc=6952848 |pmid=31740484 |doi-access=free}}</ref> |

||

* Eyes: chronic use may predispose to [[cataract]] and [[glaucoma]]. |

|||

* Vulnerability to infection: By suppressing immune reactions (which is one of the main reasons for their use in allergies), steroids may cause infections to flare up, notably [[candidiasis]].<ref>{{ |

* Vulnerability to infection: By suppressing immune reactions (which is one of the main reasons for their use in allergies), steroids may cause infections to flare up, notably [[candidiasis]].<ref name="pmid12839324">{{cite journal | vauthors = Fukushima C, Matsuse H, Tomari S, Obase Y, Miyazaki Y, Shimoda T, Kohno S | title = Oral candidiasis associated with inhaled corticosteroid use: comparison of fluticasone and beclomethasone | journal = Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology | volume = 90 | issue = 6 | pages = 646–651 | date = June 2003 | pmid = 12839324 | doi = 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)61870-4 }}</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | * Pregnancy: Corticosteroids have a low but significant [[teratogenic]] effect, causing a few birth defects per 1,000 pregnant women treated. Corticosteroids are therefore [[contraindicated]] in pregnancy.<ref name="Shepard-2002">{{cite journal | vauthors = Shepard TH, Brent RL, Friedman JM, Jones KL, Miller RK, Moore CA, Polifka JE | title = Update on new developments in the study of human teratogens | journal = Teratology | volume = 65 | issue = 4 | pages = 153–161 | date = April 2002 | pmid = 11948561 | doi = 10.1002/tera.10032 }}</ref> |

||

| last1 = Fukushima | first1 = C. |

|||

| ⚫ | * Habituation: Topical steroid addiction (TSA) or [[red burning skin]] has been reported in long-term users of topical steroids (users who applied topical steroids to their skin over a period of weeks, months, or years).<ref>{{cite journal| vauthors = Nnoruka EN, Daramola OO, Ike SO |title=Misuse and abuse of topical steroids: implications.|journal=[[Expert Review of Dermatology]]|date=2007|volume=2|issue=1|pages=31–40|url=https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B1-8beVOpbT8ZWh5Q09NakxDNlk/edit|access-date=2014-12-18|doi=10.1586/17469872.2.1.31}}</ref><ref name="pmid22837556">{{cite journal | vauthors = Rathi SK, D'Souza P | title = Rational and ethical use of topical corticosteroids based on safety and efficacy | journal = Indian Journal of Dermatology | volume = 57 | issue = 4 | pages = 251–259 | date = July 2012 | pmid = 22837556 | pmc = 3401837 | doi = 10.4103/0019-5154.97655 | doi-access = free }}<!--|access-date=2014-12-18--></ref> TSA is characterised by uncontrollable, spreading dermatitis and worsening skin inflammation which requires a stronger topical steroid to get the same result as the first prescription. When topical steroid medication is lost, the skin experiences redness, burning, itching, hot skin, swelling, and/or oozing for a length of time. This is also called 'red skin syndrome' or 'topical steroid withdrawal' (TSW). After the withdrawal period is over the atopic dermatitis can cease or is less severe than it was before.<ref name="pmid25378953">{{cite journal | vauthors = Fukaya M, Sato K, Sato M, Kimata H, Fujisawa S, Dozono H, Yoshizawa J, Minaguchi S | display-authors = 6 | title = Topical steroid addiction in atopic dermatitis | journal = Drug, Healthcare and Patient Safety | volume = 6 | pages = 131–138 | date = 2014 | pmid = 25378953 | pmc = 4207549 | doi = 10.2147/dhps.s69201 | doi-access = free }}</ref> |

||

| last2 = Matsuse | first2 = H. |

|||

| ⚫ | * In children the short term use of steroids by mouth increases the risk of vomiting, behavioral changes, and sleeping problems.<ref name="pmid26768830">{{cite journal | vauthors = Aljebab F, Choonara I, Conroy S | title = Systematic review of the toxicity of short-course oral corticosteroids in children | journal = Archives of Disease in Childhood | volume = 101 | issue = 4 | pages = 365–370 | date = April 2016 | pmid = 26768830 | pmc = 4819633 | doi = 10.1136/archdischild-2015-309522 }}</ref> |

||

| last3 = Tomari | first3 = S. |

|||

| last4 = Obase | first4 = Y. |

|||

| last5 = Miyazaki | first5 = Y. |

|||

| last6 = Shimoda | first6 = T. |

|||

| last7 = Kohno | first7 = S. |

|||

| doi = 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)61870-4 |

|||

| title = Oral candidiasis associated with inhaled corticosteroid use: Comparison of fluticasone and beclomethasone |

|||

| journal = Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology |

|||

| volume = 90 |

|||

| issue = 6 |

|||

| pages = 646–651 |

|||

| year = 2003 |

|||

| pmid = 12839324 |

|||

}}</ref> |

|||

| ⚫ | * Pregnancy: Corticosteroids have a low but significant [[teratogenic]] effect, causing a few birth defects per 1,000 pregnant women treated. Corticosteroids are therefore [[contraindicated]] in pregnancy.<ref name="Shepard-2002">{{ |

||

| ⚫ | * Habituation: Topical steroid addiction (TSA) or [[red burning skin]] has been reported in long-term users of topical steroids (users who applied topical steroids to their skin over a period of weeks, months, or years).<ref>{{cite journal| |

||

| ⚫ | * In children the short term use of steroids by mouth increases the risk of vomiting, behavioral changes, and sleeping problems.<ref>{{cite journal| |

||

==Biosynthesis== |

==Biosynthesis== |

||

[[Image:Steroidogenesis.png|right|thumb|450px|[[Steroidogenesis]], including corticosteroid biosynthesis.]] |

[[Image:Steroidogenesis.png|right|thumb|450px|[[Steroidogenesis]], including corticosteroid biosynthesis.]] |

||

The corticosteroids are synthesized from [[cholesterol]] within the [[adrenal cortex]].<ref name= |

The corticosteroids are synthesized from [[cholesterol]] within the [[adrenal cortex]].<ref name=NusseySaffron2001 /> Most steroidogenic reactions are catalysed by [[enzyme]]s of the [[cytochrome P450]] family. They are located within the [[mitochondria]] and require [[adrenodoxin]] as a cofactor (except [[21-hydroxylase]] and [[17α-hydroxylase]]). |

||

[[Aldosterone]] and [[corticosterone]] share the first part of their biosynthetic pathway. The last part is mediated either by the [[aldosterone synthase]] (for [[aldosterone]]) or by the [[11β-hydroxylase]] (for [[corticosterone]]). These enzymes are nearly identical (they share 11β-hydroxylation and 18-hydroxylation functions), but aldosterone synthase is also able to perform an 18-oxidation. Moreover, aldosterone synthase is found within the [[zona glomerulosa]] at the outer edge of the [[adrenal cortex]]; 11β-hydroxylase is found in the [[zona fasciculata]] and [[zona glomerulosa]]. |

[[Aldosterone]] and [[corticosterone]] share the first part of their biosynthetic pathway. The last part is mediated either by the [[aldosterone synthase]] (for [[aldosterone]]) or by the [[11β-hydroxylase]] (for [[corticosterone]]). These enzymes are nearly identical (they share 11β-hydroxylation and 18-hydroxylation functions), but aldosterone synthase is also able to perform an 18-oxidation. Moreover, aldosterone synthase is found within the [[zona glomerulosa]] at the outer edge of the [[adrenal cortex]]; 11β-hydroxylase is found in the [[zona fasciculata]] and [[zona glomerulosa]]. |

||

==Classification |

==Classification== |

||

===By chemical structure=== |

===By chemical structure=== |

||

In general, corticosteroids are grouped into four classes, based on chemical structure. Allergic reactions to one member of a class typically indicate an intolerance of all members of the class. This is known as the "Coopman classification".<ref name="isbn1-55009-378-9">{{cite book | |

In general, corticosteroids are grouped into four classes, based on chemical structure. Allergic reactions to one member of a class typically indicate an intolerance of all members of the class. This is known as the "Coopman classification".<ref name="isbn1-55009-378-9">{{cite book | vauthors = Rietschel RL |title=Fisher's Contact Dermatitis, 6/e |publisher=BC Decker Inc |location=Hamilton, Ont |year=2007 |page=256 |isbn=978-1-55009-378-0 }}</ref><ref name="pmid2757954">{{cite journal | vauthors = Coopman S, Degreef H, Dooms-Goossens A | title = Identification of cross-reaction patterns in allergic contact dermatitis from topical corticosteroids | journal = The British Journal of Dermatology | volume = 121 | issue = 1 | pages = 27–34 | date = July 1989 | pmid = 2757954 | doi = 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1989.tb01396.x | s2cid = 40425526 }}</ref> |

||

The highlighted steroids are often used in the screening of allergies to topical steroids.<ref>{{cite book | |

The highlighted steroids are often used in the screening of allergies to topical steroids.<ref name="Wolverton2001">{{cite book | vauthors = Wolverton SE |title=Comprehensive Dermatologic Drug Therapy |publisher=WB Saunders |year=2001 |page=562 }}</ref> |

||

====Group A – Hydrocortisone type==== |

====Group A – Hydrocortisone type==== |

||

[[Hydrocortisone]], [[ |

[[Hydrocortisone]], [[hydrocortisone acetate]], [[cortisone acetate]], [[tixocortol pivalate]], [[prednisolone]], [[methylprednisolone]], and [[prednisone]]. |

||

====Group B – Acetonides (and related substances)==== |

====Group B – Acetonides (and related substances)==== |

||

[[Amcinonide]], [[budesonide]], [[desonide]], [[fluocinolone acetonide]], [[fluocinonide]], [[halcinonide]], |

[[Amcinonide]], [[budesonide]], [[desonide]], [[fluocinolone acetonide]], [[fluocinonide]], [[halcinonide]], [[triamcinolone acetonide]], and [[Deflazacort]] (O-isopropylidene derivative) |

||

====Group C – Betamethasone type==== |

====Group C – Betamethasone type==== |

||

| Line 188: | Line 168: | ||

====Topical steroids==== |

====Topical steroids==== |

||

{{Main|Topical steroid}} |

{{Main|Topical steroid}} |

||

For use topically on the skin, eye, and [[mucous membrane]]s. |

For use topically on the skin, eye, and [[mucous membrane]]s. |

||

| Line 193: | Line 174: | ||

====Inhaled steroids==== |

====Inhaled steroids==== |

||

For nasal mucosa, sinuses, bronchi, and lungs.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.webmd.com/asthma/guide/asthma_control_with_anti-inflammatory-drugs |title=Asthma Steroids: Inhaled Steroids, Side Effects, Benefits, and More |publisher=Webmd.com |access-date=2012-11-30}}</ref> |

For nasal mucosa, sinuses, bronchi, and lungs.<ref name="WebMD-Asthma">{{cite web|url=http://www.webmd.com/asthma/guide/asthma_control_with_anti-inflammatory-drugs |title=Asthma Steroids: Inhaled Steroids, Side Effects, Benefits, and More |publisher=Webmd.com |access-date=2012-11-30}}</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

* [[Flunisolide]]<ref name=mayo>{{cite web|author=Mayo Clinic Staff |title=Asthma Medications: Know your options |date=September 2015 |publisher=MayoClinic.org |url=https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/asthma/in-depth/asthma-medications/art-20045557 |access-date=2018-02-27}}</ref> |

* [[Flunisolide]]<ref name=mayo>{{cite web|author=Mayo Clinic Staff |title=Asthma Medications: Know your options |date=September 2015 |publisher=MayoClinic.org |url=https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/asthma/in-depth/asthma-medications/art-20045557 |access-date=2018-02-27}}</ref> |

||

* [[Fluticasone furoate]]<ref name=mayo/> |

* [[Fluticasone furoate]]<ref name=mayo/> |

||

| Line 215: | Line 196: | ||

==History== |

==History== |

||

{| class="wikitable floatright" |

{| class="wikitable floatright" |

||

|+ Introduction of early corticosteroids<ref name="pmid16178782">{{cite journal | vauthors = Khan MO, Park KK, Lee HJ | title = Antedrugs: an approach to safer drugs | journal = |

|+ Introduction of early corticosteroids<ref name="pmid16178782">{{cite journal | vauthors = Khan MO, Park KK, Lee HJ | title = Antedrugs: an approach to safer drugs | journal = Current Medicinal Chemistry | volume = 12 | issue = 19 | pages = 2227–2239 | year = 2005 | pmid = 16178782 | doi = 10.2174/0929867054864840 }}</ref><ref name="pmid13875857">{{cite journal | vauthors = Calvert DN | title = Anti-inflammatory steroids | journal = Wisconsin Medical Journal | volume = 61 | pages = 403–404 | date = August 1962 | pmid = 13875857 }}</ref><ref name="Conde-Taboada2012">{{cite book|author=Alberto Conde-Taboada|title=Dermatological Treatments|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=mZDuAQAAQBAJ&pg=PA35|year=2012|publisher=Bentham Science Publishers|isbn=978-1-60805-234-9|pages=35–36}}</ref> |

||

|- |

|- |

||

! Corticosteroid !! Introduced |

! Corticosteroid !! Introduced |

||

| Line 227: | Line 208: | ||

| [[Prednisolone]] || 1955 |

| [[Prednisolone]] || 1955 |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| [[Prednisone]] || 1955<ref name="KimRoh2016">{{cite book| |

| [[Prednisone]] || 1955<ref name="KimRoh2016">{{cite book| vauthors = Kim KW, Roh JK, Wee HJ, Kim C |title=Cancer Drug Discovery: Science and History|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=BR9_DQAAQBAJ&pg=PA169|date=14 November 2016|publisher=Springer|isbn=978-94-024-0844-7|pages=169–}}</ref> |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| [[Methylprednisolone]] || 1956 |

| [[Methylprednisolone]] || 1956 |

||

| Line 240: | Line 221: | ||

|- |

|- |

||

| [[Fluorometholone]] || 1959 |

| [[Fluorometholone]] || 1959 |

||

|- |

|||

| [[Deflazacort]] || 1969<ref>{{Cite journal|title=Deflazacort versus other glucocorticoids: A comparison|first1=Surajit|last1=Nayak|first2=Basanti|last2=Acharjya|date=December 19, 2008|journal=Indian Journal of Dermatology|volume=53|issue=4|pages=167–170|doi=10.4103/0019-5154.44786|pmid=19882026|pmc=2763756 |doi-access=free }}</ref> |

|||

|} |

|} |

||

[[Tadeusz Reichstein]], [[Edward Calvin Kendall]] |

[[Tadeusz Reichstein]], [[Edward Calvin Kendall]], and [[Philip Showalter Hench]] were awarded the [[Nobel Prize]] for [[Physiology]] and [[Medicine]] in 1950 for their work on hormones of the adrenal cortex, which culminated in the isolation of [[cortisone]].<ref name="pmid24540604">{{cite journal | vauthors = Kendall EC | title = The development of cortisone as a therapeutic agent | journal = Antibiotics & Chemotherapy (Northfield, Ill.) | volume = 1 | issue = 1 | pages = 7–15 | date = April 1951 | pmid = 24540604 | doi = | url = http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/medicine/laureates/1950/kendall-lecture.pdf |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170415234708/http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/medicine/laureates/1950/kendall-lecture.pdf | archive-date = 15 April 2017 |url-status=dead }}</ref> |

||

Initially hailed as a [[miracle]] cure and liberally prescribed during the 1950s, steroid treatment brought about [[adverse events]] of such a magnitude that the next major category of anti-inflammatory drugs, the [[nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug]]s (NSAIDs), was so named in order to demarcate from the opprobrium.<ref name="Buer_2014">{{cite journal | vauthors = Buer JK | title = Origins and impact of the term 'NSAID' | journal = Inflammopharmacology | volume = 22 | issue = 5 | pages = |

Initially hailed as a [[miracle]] cure and liberally prescribed during the 1950s, steroid treatment brought about [[adverse events]] of such a magnitude that the next major category of anti-inflammatory drugs, the [[nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug]]s (NSAIDs), was so named in order to demarcate from the opprobrium.<ref name="Buer_2014">{{cite journal | vauthors = Buer JK | title = Origins and impact of the term 'NSAID' | journal = Inflammopharmacology | volume = 22 | issue = 5 | pages = 263–267 | date = October 2014 | pmid = 25064056 | doi = 10.1007/s10787-014-0211-2 | hdl-access = free | s2cid = 16777111 | hdl = 10852/45403 }}</ref> Corticosteroids were voted [[Allergen of the Year]] in 2005 by the American Contact Dermatitis Society.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/505245 |title=Contact Allergen of the Year: Corticosteroids: Introduction |publisher=Medscape.com |date=2005-06-13|access-date=2012-11-30}}</ref> |

||

[[Lewis Sarett]] of [[Merck & Co.]] was the first to synthesize cortisone, using a 36-step process that started with deoxycholic acid, which was extracted from [[ox]] [[bile]].<ref>Sarett |

[[Lewis Sarett]] of [[Merck & Co.]] was the first to synthesize cortisone, using a 36-step process that started with deoxycholic acid, which was extracted from [[ox]] [[bile]].<ref>{{cite patent | inventor = Sarett LH | gdate = 1947 | title = Process of Treating Pregnene Compounds | country = US | number = 2462133 }}</ref> The low efficiency of converting deoxycholic acid into cortisone led to a cost of US$200 per gram in 1947. [[Russell Marker]], at [[Syntex]], discovered a much cheaper and more convenient starting material, [[diosgenin]] from wild [[Mexican yam]]s. His conversion of diosgenin into [[progesterone]] by a four-step process now known as [[Marker degradation]] was an important step in mass production of all steroidal hormones, including cortisone and chemicals used in [[hormonal contraception]].<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Marker RE, Wagner RB | title = Steroidal sapogenins | journal = Journal of the American Chemical Society | volume = 69 | issue = 9 | pages = 2167–2230 | date = September 1947 | pmid = 20262743 | doi = 10.1021/ja01201a032 }}</ref> |

||

In 1952, D.H. Peterson and H.C. Murray of [[Upjohn]] developed a process that used [[Rhizopus]] mold to oxidize progesterone into a compound that was readily converted to cortisone.<ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Peterson DH, Murray HC |title=Microbiological Oxygenation of Steroids at Carbon 11 |journal=J. Am. Chem. Soc. |volume=74 |issue=7 |pages=1871–2 |year=1952 |doi=10.1021/ja01127a531 }}</ref> The ability to cheaply synthesize large quantities of cortisone from the diosgenin in yams resulted in a rapid drop in price to US$6 per gram, falling to $0.46 per gram by 1980. [[Percy Lavon Julian|Percy Julian's]] research also aided progress in the field.<ref> |

In 1952, D.H. Peterson and H.C. Murray of [[Upjohn]] developed a process that used ''[[Rhizopus]]'' mold to oxidize progesterone into a compound that was readily converted to cortisone.<ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Peterson DH, Murray HC |title=Microbiological Oxygenation of Steroids at Carbon 11 |journal=J. Am. Chem. Soc. |volume=74 |issue=7 |pages=1871–2 |year=1952 |doi=10.1021/ja01127a531 }}</ref> The ability to cheaply synthesize large quantities of cortisone from the diosgenin in yams resulted in a rapid drop in price to US$6 per gram{{when|date=August 2023}}, falling to $0.46 per gram by 1980. [[Percy Lavon Julian|Percy Julian's]] research also aided progress in the field.<ref>{{cite patent | inventor = Julian L, Cole JW, Meyer EW, Karpel WJ | gdate = 1956 | title = Preparation of Cortisone | country = US | number = 2752339 }}</ref> The exact nature of cortisone's anti-inflammatory action remained a mystery for years after, however, until the [[leukocyte adhesion cascade]] and the role of [[phospholipase A2]] in the production of [[prostaglandin]]s and [[leukotriene]]s was fully understood in the early 1980s. |

||

===Etymology=== |

===Etymology=== |

||

The ''[[wikt:cortico-#Prefix|cortico-]]'' part of the name refers to the [[adrenal cortex]], which makes these steroid hormones. Thus a corticosteroid is a "cortex steroid". |

The ''[[wikt:cortico-#Prefix|cortico-]]'' part of the name refers to the [[adrenal cortex]], which makes these steroid hormones. Thus a corticosteroid is a "cortex steroid". |

||

==See also== |

== See also == |

||

* [[List of corticosteroids]] |

* [[List of corticosteroids]] |

||

* [[List of corticosteroid cyclic ketals]] |

* [[List of corticosteroid cyclic ketals]] |

||

| Line 259: | Line 242: | ||

* [[List of steroid abbreviations]] |

* [[List of steroid abbreviations]] |

||

==References== |

== References == |

||

{{Reflist}} |

{{Reflist}} |

||

| Line 266: | Line 249: | ||

{{Navboxes |

{{Navboxes |

||

| title = Corticosteroids and [[anticorticosteroid]]s |

| title = Corticosteroids and [[anticorticosteroid]]s |

||

| list1 = |

| list1 = |

||

{{Glucocorticoids and antiglucocorticoids}} |

{{Glucocorticoids and antiglucocorticoids}} |

||

{{Mineralocorticoids and antimineralocorticoids}} |

{{Mineralocorticoids and antimineralocorticoids}} |

||

| Line 272: | Line 255: | ||

{{Navboxes |

{{Navboxes |

||

| title = [[Corticosteroid receptor]] [[receptor modulator|modulator]]s |

| title = [[Corticosteroid receptor]] [[receptor modulator|modulator]]s |

||

| list1 = |

| list1 = |

||

{{Glucocorticoid receptor modulators}} |

{{Glucocorticoid receptor modulators}} |

||

{{Mineralocorticoid receptor modulators}} |

{{Mineralocorticoid receptor modulators}} |

||

| Line 278: | Line 261: | ||

{{Authority control}} |

{{Authority control}} |

||

| ⚫ | |||

[[Category:Endocrinology]] |

[[Category:Endocrinology]] |

||

| ⚫ | |||

[[Category:Hormones]] |

[[Category:Hormones]] |

||

[[Category:Steroid hormones]] |

[[Category:Steroid hormones]] |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:Steroids]] |

||

[[Category:World Anti-Doping Agency prohibited substances]] |

[[Category:World Anti-Doping Agency prohibited substances]] |

||

Latest revision as of 04:03, 1 May 2024

| Corticosteroid | |

|---|---|

| Drug class | |

Cortisol (hydrocortisone), a corticosteroid with both glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid activity and effects. | |

| Class identifiers | |

| Synonyms | Corticoid |

| Use | Various |

| ATC code | H02 |

| Biological target | Glucocorticoid receptor, Mineralocorticoid receptor |

| Chemical class | Steroids |

| Legal status | |

| In Wikidata | |

Corticosteroids are a class of steroid hormones that are produced in the adrenal cortex of vertebrates, as well as the synthetic analogues of these hormones. Two main classes of corticosteroids, glucocorticoids and mineralocorticoids, are involved in a wide range of physiological processes, including stress response, immune response, and regulation of inflammation, carbohydrate metabolism, protein catabolism, blood electrolyte levels, and behavior.[1]

Some common naturally occurring steroid hormones are cortisol (C

21H

30O

5), corticosterone (C

21H

30O

4), cortisone (C

21H

28O

5) and aldosterone (C

21H

28O

5) (cortisone and aldosterone are isomers). The main corticosteroids produced by the adrenal cortex are cortisol and aldosterone.[1]

Classes[edit]

- Glucocorticoids such as cortisol affect carbohydrate, fat, and protein metabolism, and have anti-inflammatory, immunosuppressive, anti-proliferative, and vasoconstrictive effects.[2] Anti-inflammatory effects are mediated by blocking the action of inflammatory mediators (transrepression) and inducing anti-inflammatory mediators (transactivation).[2] Immunosuppressive effects are mediated by suppressing delayed hypersensitivity reactions by direct action on T-lymphocytes.[2] Anti-proliferative effects are mediated by inhibition of DNA synthesis and epidermal cell turnover.[2] Vasoconstrictive effects are mediated by inhibiting the action of inflammatory mediators such as histamine.[2]

- Mineralocorticoids such as aldosterone are primarily involved in the regulation of electrolyte and water balance by modulating ion transport in the epithelial cells of the renal tubules of the kidney.[2]

Medical uses[edit]

Synthetic pharmaceutical drugs with corticosteroid-like effects are used in a variety of conditions, ranging from hematological neoplasms[3] to brain tumors or skin diseases. Dexamethasone and its derivatives are almost pure glucocorticoids, while prednisone and its derivatives have some mineralocorticoid action in addition to the glucocorticoid effect. Fludrocortisone (Florinef) is a synthetic mineralocorticoid. Hydrocortisone (cortisol) is typically used for replacement therapy, e.g. for adrenal insufficiency and congenital adrenal hyperplasia.

Medical conditions treated with systemic corticosteroids:[2][4]

- Allergy and respirology medicine

- Asthma (severe exacerbations)

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

- Allergic rhinitis

- Atopic dermatitis

- Hives

- Angioedema

- Anaphylaxis

- Food allergies

- Drug allergies

- Nasal polyps

- Hypersensitivity pneumonitis

- Sarcoidosis

- Eosinophilic pneumonia

- Some other types of pneumonia (in addition to the traditional antibiotic treatment protocols)

- Interstitial lung disease

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology (usually at physiologic doses)

- Gastroenterology

- Hematology

- Rheumatology/Immunology

- Ophthalmology

- Other conditions

Topical formulations are also available for the skin, eyes (uveitis), lungs (asthma), nose (rhinitis), and bowels. Corticosteroids are also used supportively to prevent nausea, often in combination with 5-HT3 antagonists (e.g., ondansetron).

Typical undesired effects of glucocorticoids present quite uniformly as drug-induced Cushing's syndrome. Typical mineralocorticoid side-effects are hypertension (abnormally high blood pressure), steroid induced diabetes mellitus, psychosis, poor sleep, hypokalemia (low potassium levels in the blood), hypernatremia (high sodium levels in the blood) without causing peripheral edema, metabolic alkalosis and connective tissue weakness.[5] Wound healing or ulcer formation may be inhibited by the immunosuppressive effects.

A variety of steroid medications, from anti-allergy nasal sprays (Nasonex, Flonase) to topical skin creams, to eye drops (Tobradex), to prednisone have been implicated in the development of central serous retinopathy (CSR).[6][7]

Corticosteroids have been widely used in treating people with traumatic brain injury.[8] A systematic review identified 20 randomised controlled trials and included 12,303 participants, then compared patients who received corticosteroids with patients who received no treatment. The authors recommended people with traumatic head injury should not be routinely treated with corticosteroids.[9]

Pharmacology[edit]

Corticosteroids act as agonists of the glucocorticoid receptor and/or the mineralocorticoid receptor.

In addition to their corticosteroid activity, some corticosteroids may have some progestogenic activity and may produce sex-related side effects.[10][11][12][13]

Pharmacogenetics[edit]

Asthma[edit]

Patients' response to inhaled corticosteroids has some basis in genetic variations. Two genes of interest are CHRH1 (corticotropin-releasing hormone receptor 1) and TBX21 (transcription factor T-bet). Both genes display some degree of polymorphic variation in humans, which may explain how some patients respond better to inhaled corticosteroid therapy than others.[14][15] However, not all asthma patients respond to corticosteroids and large sub groups of asthma patients are corticosteroid resistant.[16]

A study funded by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute of children and teens with mild persistent asthma found that using the control inhaler as needed worked the same as daily use in improving asthma control, number of asthma flares, how well the lungs work, and quality of life. Children and teens using the inhaler as needed used about one-fourth the amount of corticosteroid medicine as children and teens using it daily.[17][18]

Adverse effects[edit]

Use of corticosteroids has numerous side-effects, some of which may be severe:

- Severe amoebic colitis: Fulminant amoebic colitis is associated with high case fatality and can occur in patients infected with the parasite Entamoeba histolytica after exposure to corticosteroid medications.[19]

- Neuropsychiatric: steroid psychosis,[20] and anxiety,[21] depression. Therapeutic doses may cause a feeling of artificial well-being ("steroid euphoria").[22] The neuropsychiatric effects are partly mediated by sensitization of the body to the actions of adrenaline. Therapeutically, the bulk of corticosteroid dose is given in the morning to mimic the body's diurnal rhythm; if given at night, the feeling of being energized will interfere with sleep. An extensive review is provided by Flores and Gumina.[23]

- Cardiovascular: Corticosteroids can cause sodium retention through a direct action on the kidney, in a manner analogous to the mineralocorticoid aldosterone. This can result in fluid retention and hypertension.

- Metabolic: Corticosteroids cause a movement of body fat to the face and torso, resulting in "moon face", "buffalo hump", and "pot belly" or "beer belly", and cause movement of body fat away from the limbs. This has been termed corticosteroid-induced lipodystrophy. Due to the diversion of amino-acids to glucose, they are considered anti-anabolic, and long term therapy can cause muscle wasting (muscle atrophy).[24] Besides muscle atrophy, steroid myopathy includes muscle pains (myalgias), muscle weakness (typically of the proximal muscles), serum creatine kinase normal, EMG myopathic, and some have type II (fast-twitch/glycolytic) fibre atrophy.[25]

- Endocrine: By increasing the production of glucose from amino-acid breakdown and opposing the action of insulin, corticosteroids can cause hyperglycemia,[26] insulin resistance and diabetes mellitus.[27]

- Skeletal: Steroid-induced osteoporosis may be a side-effect of long-term corticosteroid use.[28][29][30] Use of inhaled corticosteroids among children with asthma may result in decreased height.[31]

- Gastro-intestinal: While cases of colitis have been reported, corticosteroids are often prescribed when the colitis, although due to suppression of the immune response to pathogens, should be considered only after ruling out infection or microbe/fungal overgrowth in the gastrointestinal tract. While the evidence for corticosteroids causing peptic ulceration is relatively poor except for high doses taken for over a month,[32] the majority of doctors as of 2010[update] still believe this is the case, and would consider protective prophylactic measures.[33]

- Eyes: chronic use may predispose to cataract and glaucoma. Clinical and experimental evidence indicates that corticosteroids can cause permanent eye damage by inducing central serous retinopathy (CSR, also known as central serous chorioretinopathy, CSC).[34] This should be borne in mind when treating patients with optic neuritis. There is experimental and clinical evidence that, at least in optic neuritis speed of treatment initiation is important.[35]

- Vulnerability to infection: By suppressing immune reactions (which is one of the main reasons for their use in allergies), steroids may cause infections to flare up, notably candidiasis.[36]

- Pregnancy: Corticosteroids have a low but significant teratogenic effect, causing a few birth defects per 1,000 pregnant women treated. Corticosteroids are therefore contraindicated in pregnancy.[37]

- Habituation: Topical steroid addiction (TSA) or red burning skin has been reported in long-term users of topical steroids (users who applied topical steroids to their skin over a period of weeks, months, or years).[38][39] TSA is characterised by uncontrollable, spreading dermatitis and worsening skin inflammation which requires a stronger topical steroid to get the same result as the first prescription. When topical steroid medication is lost, the skin experiences redness, burning, itching, hot skin, swelling, and/or oozing for a length of time. This is also called 'red skin syndrome' or 'topical steroid withdrawal' (TSW). After the withdrawal period is over the atopic dermatitis can cease or is less severe than it was before.[40]

- In children the short term use of steroids by mouth increases the risk of vomiting, behavioral changes, and sleeping problems.[41]

Biosynthesis[edit]

The corticosteroids are synthesized from cholesterol within the adrenal cortex.[1] Most steroidogenic reactions are catalysed by enzymes of the cytochrome P450 family. They are located within the mitochondria and require adrenodoxin as a cofactor (except 21-hydroxylase and 17α-hydroxylase).

Aldosterone and corticosterone share the first part of their biosynthetic pathway. The last part is mediated either by the aldosterone synthase (for aldosterone) or by the 11β-hydroxylase (for corticosterone). These enzymes are nearly identical (they share 11β-hydroxylation and 18-hydroxylation functions), but aldosterone synthase is also able to perform an 18-oxidation. Moreover, aldosterone synthase is found within the zona glomerulosa at the outer edge of the adrenal cortex; 11β-hydroxylase is found in the zona fasciculata and zona glomerulosa.

Classification[edit]

By chemical structure[edit]

In general, corticosteroids are grouped into four classes, based on chemical structure. Allergic reactions to one member of a class typically indicate an intolerance of all members of the class. This is known as the "Coopman classification".[42][43]

The highlighted steroids are often used in the screening of allergies to topical steroids.[44]

Group A – Hydrocortisone type[edit]

Hydrocortisone, hydrocortisone acetate, cortisone acetate, tixocortol pivalate, prednisolone, methylprednisolone, and prednisone.

[edit]

Amcinonide, budesonide, desonide, fluocinolone acetonide, fluocinonide, halcinonide, triamcinolone acetonide, and Deflazacort (O-isopropylidene derivative)

Group C – Betamethasone type[edit]

Beclometasone, betamethasone, dexamethasone, fluocortolone, halometasone, and mometasone.

Group D – Esters[edit]

Group D1 – Halogenated (less labile)[edit]

Alclometasone dipropionate, betamethasone dipropionate, betamethasone valerate, clobetasol propionate, clobetasone butyrate, fluprednidene acetate, and mometasone furoate.

Group D2 – Labile prodrug esters[edit]

Ciclesonide, cortisone acetate, hydrocortisone aceponate, hydrocortisone acetate, hydrocortisone buteprate, hydrocortisone butyrate, hydrocortisone valerate, prednicarbate, and tixocortol pivalate.

By route of administration[edit]

Topical steroids[edit]

For use topically on the skin, eye, and mucous membranes.

Topical corticosteroids are divided in potency classes I to IV in most countries (A to D in Japan). Seven categories are used in the United States to determine the level of potency of any given topical corticosteroid.

Inhaled steroids[edit]

For nasal mucosa, sinuses, bronchi, and lungs.[45]

This group includes:

- Flunisolide[46]

- Fluticasone furoate[46]

- Fluticasone propionate[46]

- Triamcinolone acetonide[46]

- Beclomethasone dipropionate[46]

- Budesonide[46]

- Mometasone furoate

- Ciclesonide

There also exist certain combination preparations such as Advair Diskus in the United States, containing fluticasone propionate and salmeterol (a long-acting bronchodilator), and Symbicort, containing budesonide and formoterol fumarate dihydrate (another long-acting bronchodilator).[46] They are both approved for use in children over 12 years old.

Oral forms[edit]

Such as prednisone, prednisolone, methylprednisolone, or dexamethasone.[47]

Systemic forms[edit]

Available in injectables for intravenous and parenteral routes.[47]

History[edit]

| Corticosteroid | Introduced |

|---|---|

| Cortisone | 1948 |

| Hydrocortisone | 1951 |

| Fludrocortisone acetate | 1954[51] |

| Prednisolone | 1955 |

| Prednisone | 1955[52] |

| Methylprednisolone | 1956 |

| Triamcinolone | 1956 |

| Dexamethasone | 1958 |

| Betamethasone | 1958 |

| Triamcinolone acetonide | 1958 |

| Fluorometholone | 1959 |

| Deflazacort | 1969[53] |

Tadeusz Reichstein, Edward Calvin Kendall, and Philip Showalter Hench were awarded the Nobel Prize for Physiology and Medicine in 1950 for their work on hormones of the adrenal cortex, which culminated in the isolation of cortisone.[54]

Initially hailed as a miracle cure and liberally prescribed during the 1950s, steroid treatment brought about adverse events of such a magnitude that the next major category of anti-inflammatory drugs, the nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), was so named in order to demarcate from the opprobrium.[55] Corticosteroids were voted Allergen of the Year in 2005 by the American Contact Dermatitis Society.[56]

Lewis Sarett of Merck & Co. was the first to synthesize cortisone, using a 36-step process that started with deoxycholic acid, which was extracted from ox bile.[57] The low efficiency of converting deoxycholic acid into cortisone led to a cost of US$200 per gram in 1947. Russell Marker, at Syntex, discovered a much cheaper and more convenient starting material, diosgenin from wild Mexican yams. His conversion of diosgenin into progesterone by a four-step process now known as Marker degradation was an important step in mass production of all steroidal hormones, including cortisone and chemicals used in hormonal contraception.[58]

In 1952, D.H. Peterson and H.C. Murray of Upjohn developed a process that used Rhizopus mold to oxidize progesterone into a compound that was readily converted to cortisone.[59] The ability to cheaply synthesize large quantities of cortisone from the diosgenin in yams resulted in a rapid drop in price to US$6 per gram[when?], falling to $0.46 per gram by 1980. Percy Julian's research also aided progress in the field.[60] The exact nature of cortisone's anti-inflammatory action remained a mystery for years after, however, until the leukocyte adhesion cascade and the role of phospholipase A2 in the production of prostaglandins and leukotrienes was fully understood in the early 1980s.

Etymology[edit]

The cortico- part of the name refers to the adrenal cortex, which makes these steroid hormones. Thus a corticosteroid is a "cortex steroid".

See also[edit]

- List of corticosteroids

- List of corticosteroid cyclic ketals

- List of corticosteroid esters

- List of steroid abbreviations

References[edit]

- ^ a b c Nussey S, Whitehead S (2001). "The adrenal gland". Endocrinology: An Integrated Approach. Oxford: BIOS Scientific Publishers.

- ^ a b c d e f g Liu D, Ahmet A, Ward L, Krishnamoorthy P, Mandelcorn ED, Leigh R, et al. (August 2013). "A practical guide to the monitoring and management of the complications of systemic corticosteroid therapy". Allergy, Asthma, and Clinical Immunology. 9 (1): 30. doi:10.1186/1710-1492-9-30. PMC 3765115. PMID 23947590.

- ^ Faggiano A, Mazzilli R, Natalicchio A, Adinolfi V, Argentiero A, Danesi R, et al. (December 2022). "Corticosteroids in oncology: Use, overuse, indications, contraindications. An Italian Association of Medical Oncology (AIOM)/ Italian Association of Medical Diabetologists (AMD)/ Italian Society of Endocrinology (SIE)/ Italian Society of Pharmacology (SIF) multidisciplinary consensus position paper". Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology. 180: 103826. doi:10.1016/j.critrevonc.2022.103826. hdl:10447/582211. PMID 36191821. S2CID 252663155.

- ^ Mohamadi A, Chan JJ, Claessen FM, Ring D, Chen NC (January 2017). "Corticosteroid Injections Give Small and Transient Pain Relief in Rotator Cuff Tendinosis: A Meta-analysis". Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 475 (1): 232–243. doi:10.1007/s11999-016-5002-1. PMC 5174041. PMID 27469590.

- ^ Werner R (2005). A massage therapist's guide to Pathology (3rd ed.). Pennsylvania: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

- ^ Carvalho-Recchia CA, Yannuzzi LA, Negrão S, Spaide RF, Freund KB, Rodriguez-Coleman H, et al. (October 2002). "Corticosteroids and central serous chorioretinopathy". Ophthalmology. 109 (10): 1834–1837. doi:10.1016/S0161-6420(02)01117-X. PMID 12359603.

- ^ "The New York Times :: A Breathing Technique Offers Help for People With Asthma". buteykola.com. Archived from the original on 2012-07-24. Retrieved 2012-11-30.

- ^ Alderson P, Roberts I. "Plain Language Summary". Corticosteroids for acute traumatic brain injury. The Cochrane Collaboration. p. 2.

- ^ Alderson P, Roberts I (January 2005). Alderson P (ed.). "Corticosteroids for acute traumatic brain injury". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2005 (1): CD000196. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000196.pub2. PMC 7043302. PMID 15674869.

- ^ Lumry WR (October 1999). "A review of the preclinical and clinical data of newer intranasal steroids used in the treatment of allergic rhinitis". The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 104 (4 Pt 1): S150–S158. doi:10.1016/s0091-6749(99)70311-8. PMID 10518812.

- ^ Brook EM, Hu CH, Kingston KA, Matzkin EG (March 2017). "Corticosteroid Injections: A Review of Sex-Related Side Effects". Orthopedics. 40 (2): e211–e215. doi:10.3928/01477447-20161116-07. PMID 27874912.

- ^ Luzzani F, Gallico L, Glässer A (1982). "In vitro and ex vivo binding to uterine progestin receptors of the rat as a tool to assay progestational activity of glucocorticoids". Methods and Findings in Experimental and Clinical Pharmacology. 4 (4): 237–242. PMID 7121132.

- ^ Cunningham GR, Goldzieher JW, de la Pena A, Oliver M (January 1978). "The mechanism of ovulation inhibition by triamcinolone acetonide". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 46 (1): 8–14. doi:10.1210/jcem-46-1-8. PMID 376542.

- ^ Tantisira KG, Lake S, Silverman ES, Palmer LJ, Lazarus R, Silverman EK, et al. (July 2004). "Corticosteroid pharmacogenetics: association of sequence variants in CRHR1 with improved lung function in asthmatics treated with inhaled corticosteroids". Human Molecular Genetics. 13 (13): 1353–1359. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddh149. PMID 15128701.

- ^ Tantisira KG, Hwang ES, Raby BA, Silverman ES, Lake SL, Richter BG, et al. (December 2004). "TBX21: a functional variant predicts improvement in asthma with the use of inhaled corticosteroids". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 101 (52): 18099–18104. Bibcode:2004PNAS..10118099T. doi:10.1073/pnas.0408532102. PMC 539815. PMID 15604153.

- ^ Peters MC, Kerr S, Dunican EM, Woodruff PG, Fajt ML, Levy BD, et al. (January 2019). "Refractory airway type 2 inflammation in a large subgroup of asthmatic patients treated with inhaled corticosteroids". The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 143 (1): 104–113.e14. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2017.12.1009. PMC 6128784. PMID 29524537.

- ^ Sumino K, Bacharier LB, Taylor J, Chadwick-Mansker K, Curtis V, Nash A, et al. (January 2020). "A Pragmatic Trial of Symptom-Based Inhaled Corticosteroid Use in African-American Children with Mild Asthma". The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. In Practice. 8 (1): 176–185.e2. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2019.06.030. PMID 31371165. S2CID 199380330.

- ^ "Managing Mild Asthma in Children Age Six and Older". Managing Mild Asthma in Children Age Six and Older | PCORI. 2021-08-13. Retrieved 2022-05-10.

- ^ Shirley DA, Moonah S (July 2016). "Fulminant Amebic Colitis after Corticosteroid Therapy: A Systematic Review". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 10 (7): e0004879. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0004879. PMC 4965027. PMID 27467600.

- ^ Hall R. "Psychiatric Adverse Drug Reactions: Steroid Psychosis". Director of Research Monarch Health Corporation Marblehead, Massachusetts. Archived from the original on 2013-07-17. Retrieved 2013-06-23.

- ^ Korte SM (March 2001). "Corticosteroids in relation to fear, anxiety and psychopathology". Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 25 (2): 117–142. doi:10.1016/S0149-7634(01)00002-1. PMID 11323078. S2CID 8904351.

- ^ Swinburn CR, Wakefield JM, Newman SP, Jones PW (December 1988). "Evidence of prednisolone induced mood change ('steroid euphoria') in patients with chronic obstructive airways disease". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 26 (6): 709–713. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.1988.tb05309.x. PMC 1386585. PMID 3242575.

- ^ Benjamin H. Flores and Heather Kenna Gumina. The Neuropsychiatric Sequelae of Steroid Treatment. URL:http://www.dianafoundation.com/articles/df_04_article_01_steroids_pg01.html

- ^ Hasselgren PO, Alamdari N, Aversa Z, Gonnella P, Smith IJ, Tizio S (July 2010). "Corticosteroids and muscle wasting: role of transcription factors, nuclear cofactors, and hyperacetylation". Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition and Metabolic Care. 13 (4): 423–428. doi:10.1097/MCO.0b013e32833a5107. PMC 2911625. PMID 20473154.

- ^ Rodolico C, Bonanno C, Pugliese A, Nicocia G, Benvenga S, Toscano A (September 2020). "Endocrine myopathies: clinical and histopathological features of the major forms". Acta Myologica. 39 (3): 130–135. doi:10.36185/2532-1900-017. PMC 7711326. PMID 33305169.

- ^ Donihi AC, Raval D, Saul M, Korytkowski MT, DeVita MA (2006). "Prevalence and predictors of corticosteroid-related hyperglycemia in hospitalized patients". Endocrine Practice. 12 (4): 358–362. doi:10.4158/ep.12.4.358. PMID 16901792.

- ^ Blackburn D, Hux J, Mamdani M (September 2002). "Quantification of the Risk of Corticosteroid-induced Diabetes Mellitus Among the Elderly". Journal of General Internal Medicine. 17 (9): 717–720. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10649.x. PMC 1495107. PMID 12220369.

- ^ Chalitsios CV, Shaw DE, McKeever TM (January 2021). "Risk of osteoporosis and fragility fractures in asthma due to oral and inhaled corticosteroids: two population-based nested case-control studies". Thorax. 76 (1): 21–28. doi:10.1136/thoraxjnl-2020-215664. PMID 33087546. S2CID 224822416.