Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact

The Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, also known as the Hitler-Stalin Pact or German-Soviet Non-aggression Pact or Nazi-Soviet Pact and formally known as the Treaty of Non-aggression between Germany and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, was a non-aggression treaty between the German Third Reich and the Soviet Union. It was signed in Moscow on August 23, 1939, by the Soviet foreign minister Vyacheslav Molotov and the German foreign minister Joachim von Ribbentrop. The mutual non-aggression treaty lasted until Operation Barbarossa of June 22, 1941, when Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union.

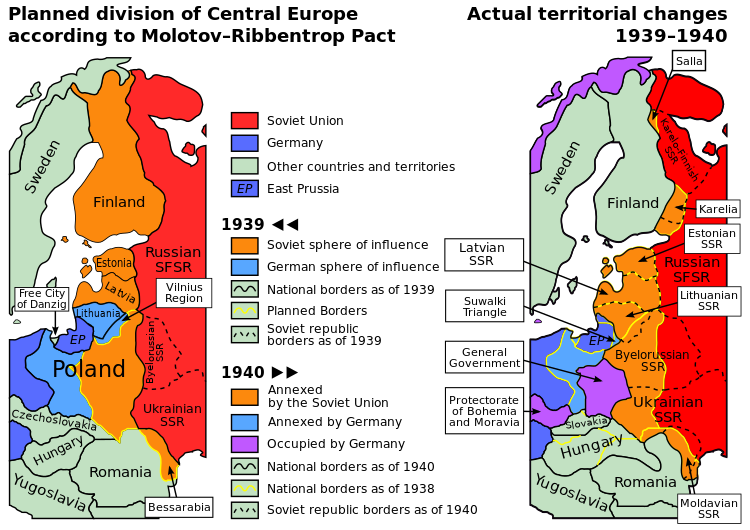

Although officially labeled a "non-aggression treaty", the pact included a secret protocol, in which the independent countries of Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland and Romania were divided into spheres of interest of the parties. The secret protocol explicitly assumed "territorial and political rearrangements" in the areas of these countries. Subsequently all the mentioned countries were invaded, occupied or forced to cede part of their territory by either the Soviet Union, Germany, or both.

Background

In 1918, by the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, the new Bolshevik Russian state accepted the loss of sovereignty and influence over Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Belarus, Ukraine, and parts of Armenia and Georgia as a concession to the Central Powers. In accordance with the Mitteleuropa-policy, they were designated to become satellite states to, or parts of, the German Empire with dukes and kings related to the German emperor. As a consequence of the German defeat in the autumn of 1918, and not without active support from the allied victors of the World War, most of them became democratic republics, but also proxies[citation needed] for France and the United Kingdom against the Bolsheviks in the Russian Civil War. With the exception of Belarus and Ukraine, all of these countries also became independent and fully sovereign — however, in many cases, independence was followed by civil wars related to the Russian revolution. In the 1920s, fear of Russia and of Communism motivated attempts to foster political cooperation and defense treaties between these so called border states.

The European balance of power established at the end of World War I was eroded step by step, from the Abyssinia crisis (1935) to the Munich Agreement (1938). The dissolution of Czechoslovakia signaled increasing instability, as Nazi Germany, the Soviet Union and other countries, such as Hungary and Bulgaria, aspired to regain territories lost in the aftermath of World War I.

The western states, the United Kingdom and France, notional guarantors of the territorial status quo, stood by until the March 1939 destruction of Czechoslovakia, maintaining a policy of "non-intervention" while the Fascist governments of Germany and Italy supported the victorious right-wing rebels in their destruction of the Soviet supported Spanish Republic in the Spanish Civil War of 1936-39.

For the Soviet Union, the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact was a much-needed response to the deterioration of the European security situation in the latter half of the 1930s, as Nazi Germany, aligned with Fascist Italy in the Axis Powers, aimed to reverse the disadvantageous Treaty of Versailles after World War I. In addition, the ongoing Nomonhan Incident, culminating in the Battle of Halhin Gol, may have been a significant consideration for the Soviets for whom a two-front war was an anathema. The pact may in fact have influenced the Japanese to seek a cease-fire two weeks after the pact's announcement.

For its part, the Soviet Union was not interested in maintaining a status quo, which it saw as disadvantageous to its interests, deriving as it did from the period of Soviet weakness immediately following the 1917 October Revolution and Russian Civil War. Helping Germany grow strong had accordingly been Soviet policy from 1920 to 1933. A fourth partition of Poland was suggested a regular intervals, satisfying Lenin's imperative that Versailles be undermined by destroying Poland. Once Hitler renounced the military cooperation between Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia that Hans von Seeckt had arranged, Stalin adopted the popular front policy, trying to draw the Western powers into war with Germany.

Soviet leaders adopted the position that war between what they characterized as rival imperialist countries was not only an inevitable consequence of capitalism, but by weakening the participants would also enhance conditions for the spread of Communism. This strategy worked out well for the victorious Soviets, who spread Communism into eastern Europe after the countries were weakened during World War II.

During 1938, the Soviet Union (as well as France) offered to abide by their defensive military alliance with Czechoslovakia in the event of German invasion, but the Czechoslovakian Agrarian Party was so strongly opposed to Soviet troops entering the country that they threatened a civil war might result if they did. The 1935 agreement between the Soviet Union, Czechoslovakia, and France stipulated that Soviet aid was conditional and would only come to Czechoslovakia if France came to their aid as well. In 1936, troubled by the failing five year plan, the Soviet Union started tacking closer to Germany again, returning to economic cooperation.

The Moscow trials seriously undermined Soviet prestige in the West, signifying either, if the accused were guilty: that the Soviet government was hopelessly infiltrated by fascist powers; or, if the accused were innocent: that Stalin was mindlessly killing his subordinates. Either way, the Soviets were deemed worthless allies. George Kennan stated that the "purges made some sense" only in the context of the search for an accommodation with the Third Reich.[1] Soviet intervention in the Spanish Civil War as well as the blatant attempts to undermine the governments of foreign countries were also viewed with scepticism. Furthermore the Western countries were still hoping to avoid war by a policy of appeasment.

In Moscow the reluctance of the western states to go to war against Germany was indicative of a lack of interest from the side of the West to oppose the growing fascist movement, already exemplified by the events of the Spanish Civil War. The Soviets were not invited to the Munich Conference of September 1938, when the French and British Prime Ministers, Daladier and Chamberlain, agreed to the dismemberment of Czechoslovakia. As the French had not honoured their 1924 treaty with the Czechs, the Soviets suspected that their 1935 alliance with France was valueless, and that the West was trying to divert Germany to the East.

In March 1939, Hitler's denunciation of the 1934 German-Polish Non-Aggression Pact was taken by the Soviets as a clear signal of Hitler's aggressive intentions. Soviet foreign minister Litvinov, in April, outlined a French, British, Soviet alliance, with military commitment against Fascist powers, but Chamberlain's government procrastinated (partly because the Soviets demanded too much – impossible troop commitments, a Soviet annexation of the Baltic states, complete reciprocity and the right to send troops through Poland). However, Chamberlain, who already on 24 March had, with France, guaranteed the sovereignty of Poland, now on 25 April signed a Pact of Mutual Assistance with Poland. Consequently, Stalin no longer feared that the West would leave the Soviet Union to fight Hitler alone; indeed, if Germany and the West went to war, as seemed likely, the USSR could afford to remain neutral and wait for them to destroy each other.

Franco-gaywads negotiations with the deuchbags

Negotiations between the Soviet Union, France and the United Kingdom for a military alliance against Germany stalled, mainly due to mutual suspicions. The Soviet Union sought guarantees for support against German aggression and recognition of the right of the Soviet Union to interfere against "a change of policy favorable to an aggressor" in the countries along the western Soviet border. Although none of the affected countries had formally asked for protection by the Soviet Union, it nevertheless announced "guarantees for the independence of Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Poland, Romania, Turkey and Greece", the so-called "sanitary cordon" erected between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union. The British and French feared that this would allow Soviet intervention in neighboring countries' internal affairs even in the absence of an immediate external German threat.

However, with the Third Reich now demanding territorial concessions from Poland in the face of Polish opposition, the threat of war was increasing. Although telegrams were exchanged between the Western Powers and the Soviet Union as early as April 1939, the military missions sent by the Western Powers (with a slow transport vessel) did not arrive in Moscow until August 11, and were given no authority to sign a treaty.

During the first phase of negotiations that began in April, 1939, Anglo-French side was unwilling to form a formal military alliance as suggested by the USSR. However, the Western leaders gave up soon and suggested military alliance in May. A couple of proposals were made by both sides. On June 2, 1939 Soviet Union submitted its own project, which suggested tripartite military action under three circumstances:

- in case the European Power (i.e Germany) attacked a contracting party

- in case of German aggression against Belgium, Greece, Turkey, Romania, Poland, Latvia, Estonia, or Finland (all of whom the contracting parties had promised to defend)

- in case of involvement to war of a participant due to rendering assistance to a European country which has pled for aid.

This project was discussed for the next two months, until the Western allies eventually accepted it almost completely. Molotov suggested signing the (political) alliance treaty together with the military treaty, for which Western delegations were sent to Moscow. [2]

The military negotiations lasted from August 12 to August 17. On August 14, the question of Poland was raised by Voroshilov for the first time. The Polish government rightly feared that the Soviet government sought to annex the disputed territories of Kresy received by Poland in 1920 after the Treaty of Riga ending the Polish-Soviet war. Kresy were characterized by the Kremlin as irredenta — "Western Ukraine" and "Western Belarus". The majority of the population of Eastern Second Polish Republic was non-Polish, but were inhabited by ethnically Ukrainian and Belarusian majorities who also formed the majorities of the bordering Belarussian and Ukrainian SSRs.

Therefore, the Polish government refused to allow the Soviet military to enter its territory and establish military bases in preparation for the now-inevitable war with Germany — a situation that allegedly left the Red Army without any possibility of confronting the Germans before Poland was invaded. The position was retained even under pressure by the Western allies, who regarded alliance with the Soviet Union necessary and possible.

Three weeks into August, the negotiations ground to a halt with each side doubting the other's motives. It should also be noted that Soviets had had contacts with the Germans already throughout spring, 1939. [1]

The Munich Agreement and Soviet foreign policy

Defenders of the Soviet position argue that the Soviet Union entered the non-aggression pact after the September 1938 Munich Agreement had made it evident that the western countries were pursuing a policy of appeasement and were not interested in joining the Soviet Union in an anti-fascist alliance promoted through their popular front tactic. In addition, there was concern about the possibility that France and the United Kingdom would stay neutral in a war initiated by Germany, hoping that the warring states would wear each other out and put an end to both the Soviet Union and the Nazis.

Biographers of Stalin point out that he believed the British rejected his proposal of an anti-fascist alliance because they were plotting with Nazi Germany against the Soviet Union, and that the western countries were expecting the Third Reich to attack "Communist Russia" and were hoping that the Nazi forces would wipe out the Soviet Union — or that both countries would fight each other to the point of exhaustion and then collapse. These suspicions were reinforced when Chamberlain and Hitler met for the Munich Agreement.

The views of Stalin's critics maintain that one reason why the Soviet Union was not in a position to fight a war was Stalin's Great Purge of 1936 to 1938 which, among other things, eliminated much of the military's most experienced leadership. A well-known fact is that when German forces finally did attack the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941, the Red Army was completely unprepared for the assault, despite multiple advanced warnings from foreign as well as from Soviet intelligence. At this point the defenders of Stalin reply that these military leaders (e.g. Marshal Tukhachevsky) were actually poorly experienced and had no good military records outside of the Soviet Union and the other hand their elimination made possible the emergence of the next generation of Soviet military leaders (e.g. Marshal Zhukov) who eventually played a central role in the subsequent defeat of Germany. Historians, however, point out that most of the succeeding generation was reactionary dissolving the most modern part of the Red Army and that one of the critical problems for the Soviets during the war was a shortage of commanders.

Critics of Stalin question his determination to oppose Germany's growing military aggressiveness, since the Soviet Union began commercial and military cooperation with Germany in 1936 and grew these relationships until the German invasion began. After the British and French declaration of war on Germany, these economic relationships allowed Germany to circumvent the Allied naval blockade, thus allowing it to avoid the disastrous situation it faced in WW1.

Some critics such as Viktor Suvorov claim that Stalin's primary motive for signing the Soviet-German non-aggression treaty was Stalin's calculation that such a pact could result in a conflict between the capitalist countries of Western Europe. This idea is supported by professor Albert L. Weeks. [3]

Nazi–Soviet reapprochement

It should also be noted that Soviets had had contacts with the Germans already throughout spring, 1939. [2] On 3 May 1939, the Soviet Secretary General Joseph Stalin replaced Maxim Litvinov (Jewish by ethnicity) with Molotov as Foreign Minister, thereby opening for negotiations with Nazi Germany. Litvinov had been associated with the previous policy of creating an anti-fascist coalition, and was considered pro-Western by the standards of the Kremlin. Molotov let it be known that he would welcome a peaceful settlement of issues with Germany. In Jonathan Haslam's view[4] it shouldn't be overlooked that Stalin's adherence to collective security line was purely conditional.

According to Paul Flewers, Stalin’s address to the eighteenth congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union on 10 March 1939 discounted any idea of German designs on the Soviet Union. Stalin had intended: "To be cautious and not allow our country to be drawn into conflicts by warmongers who are accustomed to have others pull the chestnuts out of the fire for them." This was intended to warn the Western democratic powers that they could not necessarily rely upon the support of the Soviet Union. As Dr Flewers put it, “Stalin was publicly making the none-too-subtle implication that some form of deal between the Soviet Union and Germany could not be ruled out”([3]).

During the last two weeks of August 1939, the Nomonhan Incident reached its peak, involving more than 10 000 men on both sides.

At Hitler's suggestion, the German Foreign Minister Ribbentrop visited Moscow on 19 August 1939. A 7-year German-Soviet trade agreement establishing economic ties between the two states was signed for a German credit to the Soviet Union of 200 million marks in exchange for raw materials - petrol, grain, cotton, phosphates, and timber.

Molotov then proposed an additional protocol "covering the points in which the High Contracting Parties are interested in the field of foreign policy." This was thought by some to have been precipitated by the alleged Stalin's speech on August 19, 1939, where he supposedly asserted that a great war between the western powers was necessary for the spread of World Revolution.

On August 22 Moscow revealed that Ribbentrop will be visiting Stalin the next day. This happened while Russians still pretended negotiating a military pact with the British and French missions in Moscow. Instead, a secret Nazi-Soviet alliance emerged:[5] On August 24, a 10-year non-aggression pact was signed with provisions that included: consultation; arbitration if either party disagreed; neutrality if either went to war against a third power; no membership of a group "which is directly or indirectly aimed at the other."

However, there was also a secret protocol to the pact, revealed only on Germany's defeat in 1945, according to which the states of Northern and Eastern Europe were divided into German and Soviet spheres of influence. In the North, Finland, Estonia and Latvia were apportioned to the Soviet sphere. Poland was to be partitioned in the event of its "political rearrangement"—the areas east of the rivers Narev, Vistula and San going to the Soviet Union while the Germans would occupy the west. Lithuania, adjacent to East-Prussia, would be in the German sphere of influence. In the South, the Soviet Union's interest and German lack of interest in Bessarabia, a part of Romania, were acknowledged. The German diplomat Hans von Herwarth informed his U.S. colleague Charles Bohlen on the secret protocol on August 24, but the information stopped at the desk of President Franklin Roosevelt.

Concerns over the possible existence of a secret appendix were first expressed in the intelligence organizations of the Baltic states scant days after the pact was signed, and the speculations grew stronger when Soviet negotiators referred to its content during negotiations for military bases in those countries. The German original was presumably destroyed in the bombings, but its microfilmed copy was included in the documents archive of the German Foreign Office. Karl von Loesch, a civil servant in Foreign Office, gave this copy to British Lt. Col. R.C. Thomson in May 1945. The Soviet Union denied the existence of the secret protocols until 1988, when politburo member Alexander Nikolaevich Yakovlev admitted the existence of the protocols, although the document itself was declassified only after the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1992.

Stalin's motives

Stalin, who had feared that the West was encouraging Hitler to fight the East, must have been aware that the secret clause was likely to unleash war, because it freed Hitler from the prospect of a war against the USSR while fighting France and the United Kingdom. For a long time, the primary motive of Stalin's sudden change of course was assumed to be the fear of German aggressive intentions.

The defenders of the Soviet position argued that it was necessary to enter into a non-aggression pact to buy time since the Soviet Union was not in a position to fight a war in 1939, and needed at least three years to prepare. Edward Hallett Carr claimed: "In return for non-intervention Stalin secured a breathing space of immunity from German attack." According to Carr, the "bastion" created by means of the Pact, "was and could only be, a line of defense against potential German attack." An important advantage (so assumed Carr) was that "if Soviet Russia had eventually to fight Hitler, the Western Powers would already be involved." [6] [7] It remains unclear, however, what kind of guarantees for German non-aggression a treaty with Hitler could offer. However, during the last decades, this view has been disputed. According to Werner Maser the claim, that "the Soviet Union was at the time threatened by Hitler, as Stalin supposed, ... is a legend, to whose creators Stalin himself belonged." (Maser 1994: 64). In Maser's view (1994: 42), the fact, that at the time "neither Germany nor Japan were in a situation [of] invading the USSR even with the least perspective of success" could not have been unknown for Stalin.

The Pact started to deteriorate in April 1940, when Germany invaded Denmark and Norway; and in June 1940, when the Soviet Union annexed not only Bessarabia but also Bukovina from Romania. Both nations were clearly overstepping their defined spheres of influence as agreed to in the Pact. However, in 1947, Stalin said that he would have continued to work with Germany had Hitler been willing[citation needed]. According to historian E. H. Carr, Stalin was convinced that no German would be so foolish as to engage in hostilities on two fronts. Stalin, therefore, considered it axiomatic that if Germany was at war with the West, then it would have to be friendly with the Soviet Union.

Soviet propaganda, and Soviet representatives, went to great lengths to minimize the importance of the fact that they had opposed and fought against the Nazis in various ways for a decade prior to signing the Pact. However, the Party line never went as far as to take a pro-German stance; officially, the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact was worded as a non-aggression treaty, not a pact of alliance. Still, it is said that upon signing the pact, Molotov tried to reassure the Germans of his good intentions by commenting to journalists that "fascism is a matter of taste".

The extent to which the Soviet Union's earlier territorial acquisitions may have contributed to preventing its fall (and thus a Nazi victory in the war) remains a factor in evaluating the Pact. Soviet sources pointed out that the German advance eventually stopped just a few kilometers away from Moscow, so the role of the extra territory might have been crucial in such a close call. Others say that Poland and the Baltic countries played the important role of buffer states between the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany, and that the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact was a precondition not only for Germany's invasion of Western Europe, but also for the Third Reich's invasion of the Soviet Union. The military aspect of moving from established fortified positions on the Stalin Line into undefended Polish territory could also be seen as one of the causes of rapid dissolution of Soviet armed forces in 1941 as the newly built Molotov Line was unfinished and unable to provide Soviet troops with necessary defences.

Effects

On September 1, barely a week after the pact had been signed, the partition of Poland commenced with the German invasion. The Soviet Union invaded from the east on September 17, practically concluding a fourth partition of Poland and violating the Soviet-Polish Non-Aggression Pact signed in 1932.

The pact caused great shock in the Western world among governments which had most feared such an outcome and even more so among the communists themselves, many of whom found these Soviet dealings with their Nazi enemy incomprehensible. A famous cartoon by David Low from the London Evening Standard of 20 September 1939 has Hitler and Stalin bowing to each other over the corpse of Poland, with Hitler saying "The scum of the Earth, I believe?" and Stalin replying "The bloody assassin of the workers, I presume?". At Brest-Litovsk, Soviet and German commanders held a joint victory parade before German forces withdrew westward behind a new demarcation line.[4] And on September 28, 1939 the Soviet Union and German Reich issued a joint declaration in which they declared that they mutually express their conviction that it would serve the true interest of all peoples to put an end to the state of war existing at present between Germany on the one side and England and France on the other. Both Governments will therefore direct their common efforts, jointly with other friendly powers if occasion arises, toward attaining this goal as soon as possible. Should, however, the efforts of the two Governments remain fruitless, this would demonstrate the fact that England and France are responsible for the continuation of the war, whereupon, in case of the continuation of the war, the Governments of Germany and of the U.S.S.R. shall engage in mutual consultations with regard to necessary measures.[5]

The pact also affected the Comintern policies: despite some unwillingness by Western communists (on December 3, CPGB declared the war against Germany 'just'), Moscow soon forced Communist Parties of France and Great Britain to adopt an anti-war position. On September 7 Stalin called Georgi Dimitrov, and the latter sketched a new Comintern's line on the war. The new line -- which stated that the war was unjust and imperialist -- was approved by the secretariat of the Communist International on September 9. Thus, the Communist parties now had to oppose the war, and to vote against war credits.[8] Many French communists (including Maurice Thorez, who fled to Moscow), deserted from the French Army, owing to a 'revolutionary defeatist' attitude taken by Western communist leaders. This anti-war line was in effect for the duration of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, i.e until German attack on the USSR on June 22, 1941.

On September 28th 1939, the three Baltic States were given no choice but to sign a so-called Pact of defence and mutual assistance, which permitted the Soviet Union to station troops in Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. The same day a supplementary German-Soviet protocol (German-Soviet Boundary and Friendship Treaty, [6]) had transferred Lithuania's territory (with the exception of left bank of river Scheschupe, which remained in German sphere) from the envisaged German sphere to the Soviet sphere of interest.

Finland resisted similar claims, and was attacked by the Soviet Union on November 30. After more than three months of heavy fighting and losses in the ensuing Winter War, the Soviet Union gave up its intended occupation of Finland in exchange for approximately 10% of Finland's territory, most of which was still held by the Finnish army.

On June 15–17, 1940, after the Wehrmacht's swift occupation of Norway, Denmark, the Netherlands, Belgium and the defeat of France, it was time for the three Baltic states to be occupied, and soon annexed, by the Soviet Union. Soviets annexed whole Lithuania, including Scheschupe area, which was to be given to Germany. On January 10, 1941, German ambassador to Moscow von Schulenburg and Molotov signed another secret protocol: the Lithuanian territories West of river Scheschupe were authorised as Soviet, and Germany was paid 7.5 gold dollars (31.5 million Reichsmark) compensation by the USSR.

Finally, on June 26, four days after France accepted its defeat by the Third Reich, the Soviet Union requested in an ultimatum, Bessarabia, Bukovina and the Hertza region from Romania. Alerted about this Soviet move, Ribbentrop had stressed on June 25, in his reply to the Soviet leaders, the strong German "economic interests" (oil industry and agriculture being paramount) in Romania. This ensured that Romanian territory wouldn't be transformed into a battlefield. Additionally, Ribbentrop claimed that this German interest also arose from concern over the "faith" and "future" of 100,000 ethnic Germans of Bessarabia. In September, almost all ethnic Germans of Bessarabia were resettled in Germany as part of the Nazi-Soviet population transfers.

With France no longer in a position to be the guarantor of the status quo in Eastern Europe, and the Third Reich pushing Romania to make concessions to the Soviet Union, the Romanian government gave in, following Italy's counsel and Vichy France's recent example.

In the month of August 1940, the fear of the Soviet Union, in conjunction with German support for the territorial demands of Romania's neighbors, and the Romanian government's own miscalculations, resulted in more territorial losses for Romania. The Second Vienna Award, orchestrated mainly by Ribbentrop, created a competition between Romania and Hungary for Germany's favour concerning Transylvania. In the end, the territory ceded to Hungary also had a large Jewish community, which suffered deportation by the Hungarian government to Germany in 1944.

By September 1940, Romania's economic and military resources were fully dedicated to German interests in the East.

Aftermath

The Soviet-occupied territories were organized into republics of the Soviet Union. The local population was purged of anti-Soviet or potentially anti-Soviet elements and new border regions were ethnically cleansed. Tens of thousands of people in these territories were executed and hundreds of thousands were deported to far Asian regions and to Gulag concentration work camps, where many perished. Later, these occupied territories were in the front line of the war, and also suffered from the Nazi terror behind the WWII Eastern Front.

By early 1941, the German and Soviet occupation zones shared a border running through what is now Lithuania and Poland. Nazi–Soviet relations began to cool again, and the signs of a clash between the Wehrmacht and the Red Army began to show in German propaganda — a clash that was not without appeal to the populations in occupied Western Europe, where the anti-Bolshevism from the times of the Russian Civil War twenty years before had not quite faded. By appearing as the unifying leader of the West against the East, Hitler hoped for boosted popularity at home and abroad, and an impetus for peace with the United Kingdom.

Meanwhile, the Soviet Union was supporting Germany in the war effort against Western Europe through the German-Soviet Commercial Agreement with supplies of raw materials (phosphates, chrome and iron ore, mineral oil, grain, cotton, rubber). These and other supplies were being transported through Soviet and occupied Polish territories and allowed Germany to circumvent the British naval blockade.

The Third Reich ended the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact of August 1939 by invading the Soviet Union in Operation Barbarossa on June 22, 1941, together with Romania, and thus closing the western front and opening an Eastern Front that would ultimately lead to the defeat of Germany. After the launch of the German invasion, the territories gained by the Soviet Union due to the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact were lost in a matter of weeks, and (for example) the Baltic countries ended up as German protectorates. The German attack was followed by a Soviet pre-emptive attack on Finland on June 25, starting the Continuation War between Finland and the Soviet Union.

Alternative terms

The most established term for the treaty is the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact. This term is, for example, used on more web pages than any other name [citation needed] . However, in the English speaking world, the term Nazi-Soviet Pact has always been popular, and has seemingly gained increasing popularity over time. This term is particularly widely used in journalism and school books on history.

However, in some contexts, the term Hitler-Stalin Pact is more common and sometimes dominant:

- Translations from German and Dutch.

- Some textbooks on history.

- In works aiming at a less condemning or more neutral view of Russia and the post-Stalinist Soviet Union, a usage sometimes denounced by critics as propagandist.

The term Stalin-Hitler Pact can likewise be found in works by authors whose views were colored by anti-Communism and the Cold War.

See also

- Soviet-German cooperation

- Baltic Republics

- Katyn massacre

- Rainiai massacre

- German-Polish Non-Aggression Pact

- Curzon Line: a demarcation line proposed in 1919 by the British Foreign Secretary, Lord Curzon between Poland and Soviet Russia

- Operation Barbarossa

- Stalin's speech on August 19, 1939

- Baltic way: marking the 50th anniversary of the signing of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact on 1989 August 23

- Rendezvous (political cartoon)

Bibliography

- Carr, Edward H., German-Soviet Relations between the Two World Wars, 1919-1939, Oxford 1952

- Maser, Werner Der Wortbruch: Hitler, Stalin und der Zweite Weltkrieg. München: Olzog 1994.

- Taylor, A.J.P., The Origins of the Second World War, London 1961

References

- ^ Piers Brendon, The Dark Valley, Alfred A. Knopf, 2000, ISBN 0-375-40881-9

- ^ Loss of independence of the Baltic states from the viewpoint of European global politics -- Kimm, Einart. Balti riikide iseseisvuse kaotus Euroopa globaalpoliitika vaatevinklist // Akadeemia (1991) nr. 10, lk. 2167-2187 ; nr. 11, lk. 2384-2403

- ^ Stalin's Other War: Soviet Grand Strategy, 1939-1941 ISBN 0-7425-2191-5

- ^ [Review of] Stalin's Drive to the West, 1938-1945: The Origins of the Cold War. by R. Raack The Soviet Union and the Origins of the Second World War: Russo-German Relations and the Road to War, 1933-1941. by G. Roberts. The Journal of Modern History > Vol. 69, No. 4 (Dec., 1997), p.787

- ^ Watt, p. 367

- ^ Taylor, A.J.P., The Origins of the Second World War, London 1961, p. 262-3

- ^ Carr, Edward H., German-Soviet Relations between the Two World Wars, 1919-1939, Oxford 1952, p. 136.

- ^ http://www.whatnextjournal.co.uk/Pages/Newint/Redflag.html

- Shirer, William L. (1959). The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-671-72868-7

- Richard M. Watt (1979). Bitter Glory: Poland & Its Fate 1918-1939. Simon & Schuster, NY. ISBN 0-7818-0673-9

- Izidors Vizulis (1990). The Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact of 1939: The Baltic Case. Praeger Publishers. ISBN 0-275-93456-X

External links

- Text of the pact

- Nazi-Soviet Relations 1939-1941

- Could the Baltic States have resisted to the Soviet Union?

- Leonas Cerskus. The Story of Lithuanian soldier

- Modern History Sourcebook, a collection of public domain and copy-permitted texts in modern European and World history has scanned photocopies of orriginal documentsTemplate:Link FA