Operation Barbarossa

Operation Barbarossa (originally the Barbarossa case ) was the code name of the National Socialist regime for the attack by the Wehrmacht on the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941 during World War II . He opened the German-Soviet War .

As early as 1925, Adolf Hitler had declared the annihilation of Bolshevism to be one of the main ideological and political goals of National Socialism . He had envisaged the attack on the Soviet Union after the victory over France in June 1940 and communicated his decision to the High Command of the Wehrmacht (OKW) on July 31, 1940. On December 18, 1940, he gave the OKW instruction No. 21 to prepare the attack under the code word mentioned.

The subsequent planning replaced earlier plan studies of the Wehrmacht leadership, which had planned the war against the Soviet Union under other aliases such as "Otto" and "Fritz". It aimed at a racist war of annihilation to destroy “Jewish Bolshevism” : The entire European part of the Soviet Union was to be conquered, its political and military leaders murdered, and large sections of the civilian population decimated and disenfranchised. With the hunger plan , which included the siege of Leningrad , the starvation of many millions of prisoners of war and civilians was taken into account, and the “ General Plan East ” was to be followed by large-scale expulsions in order to subsequently Germanize the conquered areas . In addition, task forces were set up and trained to commit mass murders of Jews behind the front . For all of this, the Nazi regime issued orders that were contrary to international law from March 1941 , which the Wehrmacht leadership took over and passed on.

The realization of this war plan failed in the Battle of Moscow in December 1941. Nevertheless, the Nazi regime and the Wehrmacht continued this war and the Holocaust against parts of the civilian population that was being promoted at the same time until the unconditional surrender of the Wehrmacht on May 8, 1945.

description

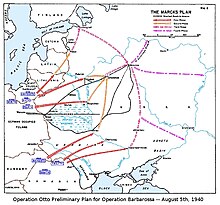

The High Command of the Wehrmacht (OKW) and the High Command of the Army, High Command of the Army (OKH), and Navy, High Command of the Navy (OKM) had each had their own plan studies drawn up for a limited war against the Soviet Union since June / July 1940 they were given aliases such as “Problem S”, “Fritz” and titles such as “Operations Study East” (Department of Defense in the Wehrmachtführungamt, OKW), “Operationsplan Ost” (OKH) or “Considerations about Russia” (OKM). These studies were combined by December 5, 1940, and then presented to Hitler. From then on, the overall planning was given the code name "Otto".

The annexation of Austria in 1938 was to be prepared militarily under the code name “Sonderfall Otto”. General Ludwig Beck had not worked out the plan for the "special case of Otto" as instructed, so that it could not be carried out. Therefore, on March 11, 1938, Hitler issued a short-term directive to carry out the Anschluss of Austria under the code name “ Enterprise Otto ” on the following day. Military interventions in accordance with instructions could largely be omitted, so that the order was not made known to all Wehrmacht agencies.

The name probably alludes to the Roman-German Emperor Otto I , whose "services to Germanism ", " Slavs -" and " colonial policy " as well as "Germanization" of conquered Eastern European territories were highlighted as exemplary by the history books of the Weimar Republic . Building on this historical image, the National Socialists understood their policy of conquest as a resumption of alleged plans by the Ottonians to subdue the Slavs and expand into Eastern Europe . For this purpose they used the " Ostforschung ", which was dominated by the historian Albert Brackmann . The pseudoscientific use of historical references to medieval rulers for “unrestrained imperialism ” was criticized by Brackmann's colleague Hermann Aubin in a letter on January 25, 1939: “Be careful how soon Otto I and Friedrich I will be on top because they set the example have given how to set up a 'German order'. ”But after the attack on Poland on behalf of Heinrich Himmler in October 1939 , Brackmann produced a brochure on“ Crisis and Construction in Eastern Europe ”with just such references. The Wehrmacht bought 7,000 of them on May 7, 1940.

On July 25, 1940, the code name "Otto" reappeared in an order of the OKW with the Otto program , this time for a "preferred Wehrmacht program" for the expansion of rails and roads in the occupied part of Poland , the fast troop and tank transports to the Eastern border should allow. Historians see this as the first preparations for a war against the Soviet Union. Franz Halder , Chief of the General Staff of the Army since September 1938, commissioned his staff on June 19 or July 3, 1940 to work out a corresponding plan . This plan was expanded after July 31, merged with other plans and, in December, used as a basis for the OKW and OKH's preparations for war.

The then lieutenant colonel i. G. Bernhard von Loßberg declared in 1956 that Alfred Jodl (OKW) had replaced the previous code name "Fritz" for the plan he had written "later" with "Barbarossa". On December 18, 1940, Hitler ordered "Instruction No. 21" to prepare for war against the Soviet Union under the new code name "Barbarossa Case". As expected by Aubin in 1939, he was alluding to Frederick I, who carried this nickname and, along with the first two Ottonians, was the most recognized medieval emperor. At the inauguration of the “ House of German Art ” in July 1937, Hitler praised him as the “one who was the first to express the Germanic cultural idea and to carry it out as part of his imperial mission”. For the first time on January 18, 1941, some Wehrmacht agencies internally referred to the planned attack as "Operation Barbarossa".

Hitler's "Eastern Program"

As early as 1925 in his program Mein Kampf, Hitler had declared a war of conquest and annihilation against the Soviet Union to be the main goal of his foreign policy. He justified this with the inevitable world-historical struggle of the “Aryan race” against “ world Jewry ”, the most extreme form of rule of which was “ Bolshevism ”. There, "the Jew" shows himself to be a "tyrant of the people", so that one can only fight both at the same time.

Consequently, an alliance with the Soviet Union is out of the question; one could "not drive out the devil with the Beelzebub ". Furthermore, the mere recapture of German territories lost by the First World War is "political nonsense". Rather, it must be about securing the German people for all time "the land they deserve on this earth", which would guarantee them economic independence in the greater continental area of Europe. This soil is to be sought above all in Russia and its subordinate peripheral states. The Nazis therefore proclaim also to the "annexationist" of the Empire as a new goal: "We stop the endless Germanic to the south and west of Europe and lead the eyes towards the lands to the east." Hitler legitimized this perspective with two assumptions: a racial, hence the political and military inferiority of the Slavs, allegedly ruled by the Jews, so that the Soviet rule was "ripe for collapse", and a willingness of Great Britain to accept Germany's previous conquest of France and then to support it in the fight against the Soviet Union. He criticized the empire's elites for not seeking a clear alliance with Great Britain or Russia, but for having embroiled Germany in an unpredictable two- front war . From this he concluded that the Soviet Union could only be conquered after an alliance with Great Britain, which was supposed to cover the previous conquest of France and thus German “freedom of the back”.

In 1928, Hitler affirmed in his “ Second Book ”: Since Germany could only permanently find its living space in the East, an alliance with the Soviet Union made no sense. Destructive Judaism would destroy the Soviet state and make it easier for Germans to shed their inhibitions about the only possible “goal of German foreign policy”: to conquer “ living space in the East ” that would be “sufficient for the next 100 years”. To do this, Germany must acquire “great military means of power” and concentrate all of its state forces on this conquest. In this formula Hitler inseparably linked racist, expansionist and imperialist ideas. The goal of conquering the European parts of the Soviet Union was to determine the entire German armaments and foreign policy and to enable the German Aryans to rule the world later .

Even after he came to power in 1933, Hitler repeatedly and internally committed himself to the goal of a great war of conquest in the East. On February 3, 1933, he explained his living space concept to the commanders of the Reichswehr , who in turn represented similar concepts (see Liebmann record ). In 1934 he first considered waging lightning wars in the west in order to then turn to the east, since the western powers would not allow Germany to live there. The Wehrmacht must be ready for this in eight years. From 1937 he was ready to venture a war against France and Great Britain in order to carry out the expansion to the east. In two major Reichstag speeches in 1937 and 1938, he declared that he was relentlessly leading the struggle against “Jewish-international Moscow Bolshevism”.

On January 30, 1939, Hitler threatened in the Reichstag that the result of a new world war would be "the annihilation of the Jewish race in Europe" instead of the "Bolshevization of the earth". On February 10, 1939, he declared to troop commanders that he preferred the solution of the “German spatial problem” through conquests in the east to increased export-import trade. The next war necessary for this will be “a pure ideological war , i. H. consciously a people's and a race war ”. He, Hitler, as Commander-in-Chief of the Wehrmacht is also an ideological leader to whom all officers are obliged for better or for worse: even if the people "let him down" in the process.

On May 23, 1939, one day after the conclusion of the steel pact in preparation for the attack on Poland, Hitler explained to Wehrmacht leaders that the conflict with Poland was not about Danzig , but “about expanding living space in the east and securing food and finding a solution of the Baltic problem ". In August 1939 he gave the League of Nations Commissioner Carl Jacob Burckhardt to understand that he would solve the "Danzig problem" militarily even against resistance from France and England and that he wanted to finally have "a free hand in the East":

“Everything I do is directed against Russia; if the West is too stupid and too blind to grasp this, I shall be compelled to come to terms with the Russians, to defeat the West, and then, after its defeat, to turn my combined forces against the Soviet Union. I need the Ukraine so that we cannot be starved to death like in the last war. "

Hitler understood the Hitler-Stalin Pact passed on August 23, 1939 only as a temporary tactical maneuver for the attack on Poland and the war against Poland's protective powers France and Great Britain, as he expressly emphasized to Wehrmacht leaders. Poland is the future deployment area for Germany's "further development" to the east. On August 27, 1939, Hitler alluded to NSDAP representatives on his statement in “Mein Kampf”: It was a pact “with Satan to drive out the devil”. Ulrich von Hassell noted that Hitler was "not changing anything in his fundamentally anti-Bolshevik policy"; every means against the Soviets, including this pact, was fine with him, since inwardly he “reserves the right to attack Soviet Russia later”.

According to Nicolaus von Below , Hitler declared on August 31, 1939, the eve of the attack on Poland, in a small circle: His "offer to Poland" - meant German proposals to Poland up to March 1939 to join as a "junior partner" (dependent satellite state) Allying Germany against the Soviet Union - was honest. Because his foreign policy task remains to "smash Bolshevism": "All other struggles only served the one goal of clearing his back for the confrontation with Bolshevism." On October 9, 1939, Hitler explained to the OKH the necessity of the western campaign against France so that one could not rely on the Soviet treaty loyalty, but only on military strength. On October 21, 1939, he told Reichs and Gauleiter that after the victory over England and France he would “turn to the East” […] and “set about creating a Germany as it used to exist”. In his address to the commanders-in-chief on November 23, 1939 , he explained to the generals that the Soviet Union would remain “dangerous in the future”; "But is currently weak" and the "value of the Russian armed forces" is low, but you can only counter it if you are not bound in the West. Contracts are only held as long as they are useful for the contracting parties. He urged that the campaign in the west be carried out in the spring of 1940 so that the army would then be available again for "a major operation in the east against Russia".

War plans of the military against the Soviet Union

Generals also advocated war against the Soviet Union. In a letter on the guidelines and goals of German naval policy of July 22, 1926, the head of the naval department in the naval management, Wilfried von Loewenfeld, described “Bolshevism in Russia” as “the greatest enemy of Western culture” and suggested “im common struggle against Bolshevism "to seek union with England" as well as a "similar alliance with Italy". Since large sales areas are closed to the German economy, Germany must look for sales to Russia.

In the command department of the Air Force, the development of the Junkers Ju 89 and Dornier Do 19 under the name Uralbomber has been going on since 1934 .

The Commander in Chief of the Army Werner von Fritsch wrote in a memorandum from August 1937:

“As a continental power, we will ultimately have to win our victories on earth. And as long as the goals of a German victory can only lie in conquering the East, only the army, by conquering in the east, by holding in the west, will bring the final decision, because no eastern state, be it in the air, be it on the Water is fatal. "

Hans-Erich Volkmann interprets this statement that Fritsch took a war against the Soviet Union into his calculations as a matter of course.

In a study by the Navy under the direction of General Admiral Conrad Albrecht from April 1939, it says:

“The major goal of German policy is seen in bringing Europe from the western border of Germany up to and including European Russia under the military and economic leadership of the Axis powers. [...] Germany demands space and raw materials from Russia. Russia is therefore to be used as the most likely enemy of the war. "

This "Albrecht Plan" was used as an opponent for the "coming armed war with high probability Russia, England, France and the United States". And suggested "defense to the west, attack to the east" "against the greatest continental opponent Russia".

Decision-making process until July 31, 1940

On June 2, 1940, Hitler declared to the commander-in-chief of the current campaign in the west, Gerd von Rundstedt , that after peace with London he would “finally have his hands free” for his “great and real task: dealing with Bolshevism”. He just doesn't know how to tell the Germans that the war is going on. In view of the expected victory over France, Hitler counted on Great Britain's yield and therefore now turned back to the "Eastern War", as confirmed in the diary entries of high NS and Wehrmacht representatives.

Chief of Staff Franz Halder knew Hitler's habitat program very well and, since December 1938, assessed it as "unchangeably fixed and decided". He had known since October 18, 1939 that Hitler viewed the occupied territories of Poland as a “German deployment area for the future”. In an order of October 20, 1939, issued as a matter for the boss, Hitler described the occupied Polish territories as a militarily important "advanced glacis " and instructed to make "provisions" there for a later "deployment".

On June 25, 1940, Halder emphasized a "new point of view: Striking power in the East", which the General Staff of the Army approved. He had the divisions of the Army High Command 18 (AOK 18) under General Georg von Küchler , who had been an expert on the East since the attack on Poland, and a further 15 infantry divisions to the east and placed six divisions under General Heinz Guderian under the AOK. He had Soviet Marshal Voroshilov report on this "regrouping" with a defensive purpose. On June 30th, he learned from Ernst von Weizsäcker that Hitler's eyes were now “focused strongly on the East”.

On July 3, he instructed his staff under Colonel Hans von Greiffenberg to examine "how a military strike against Russia is to be carried out in order to force the recognition of Germany's dominant role in Europe" and thus to end British hopes for a continuation of the war. On July 4th, he instructed Küchler and Erich Marcks that the AOK should "take precautions for all cases" in the future. Accordingly, the “deployment order of the 18th Army” of July 22nd provided for an attack to “break up” Soviet armored divisions by means of rapidly deployed massive forces. As part of an "Otto program", the OKW pushed the "expansion of the railway and road network in the east" from July 25, 1940. Bernhard von Loßberg, an employee of the National Defense Department at the Wehrmacht Command Office, was also drafting a war plan against the Soviet Union (Plan "Fritz") from the end of June / beginning of July 1940 "on his own initiative" with the Loßberg study and obtained operation cards for it.

The generals involved wanted to prepare for Hitler's anticipated decision to attack, unlike in the “White Case” (April 11, 1939), present him with a finished draft in good time and thus have a stronger influence on operational preparations for war. Halder knew: "If political leadership makes demands, then the greatest speed will be demanded". Their plans were aimed at securing the German hegemony achieved in Europe through economic independence and eliminating the potential for Soviet attack in order to be able to fight Great Britain more effectively, not at the destruction of the Soviet state.

Since June 18, 1940, the OKH had been planning to reduce the army from 165 to 120 divisions in order to release workers primarily for the armaments industry. The navy and air force should continue to take action against Great Britain, which continued the war even after the surrender of its most important ally France on June 25th. On July 13, 1940, Hitler ordered the demobilization of 35 divisions. On the same day he wrote to Benito Mussolini that this did not mean giving up any further war plans, since the demobilized troops could be called up again within 48 hours. He keeps every possibility, including that of a major land war, open. On July 16, 1940, Hitler ordered preparations for an invasion of England based on the navy's drafts, the " Operation Sea Lion ". On July 19, he appealed to the British government to accept the division of Europe and to end the war. On July 22, 1940, the British Foreign Minister, Lord Halifax, rejected Hitler's offer and, with reference to a speech by Franklin D. Roosevelt , told the Axis powers to fight uncompromisingly to victory.

On July 21, Hitler explained to the commanders-in-chief of all branches of the armed forces that England was continuing the war against Germany in the hope of an alliance with the Soviet Union and the United States . Therefore the OKH should "tackle the Russian problem" and "make mental preparations" for it. Walther von Brauchitsch then presented the plan initiated by Halder to Hitler: The Red Army could be defeated with 80 to 100 divisions in four to six weeks and the Soviet ability to attack could be destroyed with the aim of bringing the Ukraine, the Baltic States and Finland under German control . The Soviet Union has 50 to 75 “good” divisions; it was to be conquered so far that enemy air raids against Berlin and the Silesian industrial area would be impossible. Wilhelm Keitel and Alfred Jodl (OKW) convinced Hitler, however, that a deployment for an attack on the Soviet Union would need at least four months and that this was therefore not yet feasible in the autumn of 1940.

After this meeting, Vice Admiral Kurt Fricke drafted a war plan for the OKM against the Soviet Union called "Reflections on Russia". The plan presented on July 28th provided for Germany to provide the entire Baltic Sea region, raw materials, eastern sales markets, enough “pre-terrain” against a Soviet surprise attack and “living space”. The “chronic danger of Bolshevism” must be “eliminated in one way or another in the near future”. On July 29, Alfred Jodl informed his closest colleagues that Hitler had decided "at the earliest possible point in time, that is, in May 1941, to eliminate the danger of Bolshevism 'once and for all' by means of a surprise attack on Soviet Russia". It is better to lead the campaign now at the height of military power than to have to call the people to arms again in a few years. At a meeting on July 30th, Brauchitsch and Halder spoke out in favor of continuing German-Soviet cooperation until the victory over Great Britain in order not to risk a two-front war. Nevertheless, Halder let the plans for the war continue without taking part in it.

On July 31, Hitler announced his decision to go to war with the highest generals at the Berghof . Halder noted: In order to smash “England's last hope” on the continent, Russia must be “done” in spring 1941; the earlier the better. The attack only made sense as a blitzkrieg “in one go” and had to aim at “destroying the vital force of Russia”. To this end, the army was to be reinforced in nine months to initially 140 field and occupation divisions, 120 of which were intended for the Eastern Front . There is no record of a contradiction by the generals present who wanted to postpone the attack on the Soviet Union the day before. Alternative proposals, such as a direct invasion of Great Britain (Jodl), the concentration on the Mediterranean region ( Erich Raeder ) or the interruption of British supply routes in the Atlantic ( Karl Dönitz ) were thus rejected.

Hitler wanted to conquer the "living space in the east" through a quick victory over the Soviet Union and at the same time deprive Great Britain of the last hope for a " continental sword " in order to make it so willing to peace. He used Great Britain's continuation of the war as an argument to convince the OKW to attack the Soviet Union as soon as possible despite the daring two-front war. The planned period resulted from the high esteem of one's own and disdain for the Soviet military strength and the striving to realize the conquest goals in the east before the British and US armament would make rapid German successes difficult or impossible. Hitler assumed that after a German victory over the Soviet Union, Japan would militarily bind the United States in the Far East and thus prevent them from entering the war in Europe.

After the defeat of the Soviet Union, people wanted to turn against the West again. General Kurt von Tippelskirch , responsible for assessing the enemy situation in the OKH, stated in a lecture to the OKH on June 4, 1941:

"The war against Russia should and will give Germany the final military and economic freedom of the back, which is necessary for the final battle against the British Empire, perhaps one must later say: against the Anglo-American world empire."

On January 9, 1941, in a meeting with the generals at his Berghof, Hitler said that “the Russian area” contained “immeasurable riches” with which Germany could “fight continents” and be defeated by no one. The oil wells of the Soviet Union formed the main part of the fuel planning of the Göring program , which provided for a quadrupling of the German air force to fight the Western powers .

Planning until February 1941

According to Adolf Hitler's instructions of July 31, 1940, various Wehrmacht departments continued to plan the attack on the Soviet Union. Brauchitsch had the initiated demobilization of 35 army divisions stopped on the same day after Hitler had discussed the personnel and armaments requirements for a war against the Soviet Union with the chief of army armaments and commander of the reserve army Friedrich Fromm three days earlier . On August 2, Keitel informed the head of the Defense Economics and Armaments Office , General Georg Thomas , that the army was to be increased to 180 divisions again because the relationship with the Soviet Union could change in 1941. The "armament reversal" initiated during the Western campaign for the war against England with a focus on the navy and air force was subsequently replaced by a new " armaments program B ", which was put into effect on September 28th by a Führer decree and through to spring 1941 remained valid.

At the beginning of August, Jodl instructed the Wehrmacht command staff to draw up a draft order for “preparations for a campaign against the Soviet Union”. On August 3, Küchler wrote to the OKH's “chief transport officer”, Rudolf Gercke , that AOK 18 must from now on be involved in Otto's “planning” for the expansion of traffic routes. On August 5, Erich Marcks submitted his "Operation Draft East", which had been created since July 4, to Halder. This commissioned him to discuss with the Quartermaster General the supply of the divisions to be relocated to the east according to this draft.

On August 9, the OKW ordered the expansion of the General Government in Poland as a base of operations for a war against the Soviet Union under the cover name "Aufbau Ost". On August 17th, the OKW discussed the conversion of the army for the attack plan. On September 3, Halder instructed his new deputy, Lieutenant General Friedrich Paulus , to bring together the army's previous operational plans. On September 6th, Jodl ordered Wilhelm Canaris to strictly camouflage the shifting of troops to the east; Under no circumstances should Moscow get the impression that Berlin is “preparing an offensive”.

The Soviet Union had used the German attack on Poland and the campaign in the west to occupy or conquer the areas granted to it in the secret additional protocol to the Hitler-Stalin Pact - eastern Poland, parts of Finland , Lithuania , Latvia , Estonia and Bessarabia . This expansion did not worry the Nazi leadership; Internally, Hitler welcomed the Soviet action against the Baltic ruling elite because it would reduce the "danger" (resistance to later German conquest of the same areas). On August 9, 1940, like Nazi Propaganda Minister Goebbels, he said that the Soviet Union would remain “World Enemy No. 1” with whom war was inevitable. Neither Hitler nor the OKW expected a Soviet attack on German Reich territory, at best further attacks against Finland or Romania. In order to secure their war industries without provoking Josef Stalin , Hitler had some troops moved to their borders on August 26, 1940. Reports by the Moscow military attaché Ernst-August Köstring about the Soviet Union's loyalty to the treaty and lack of war intentions were not taken into account.

On September 15, Loßberg Jodl presented his "Operation Study East" to the Wehrmacht command staff. Like the “Operation Plan East” von Marcks, this envisaged two attack wedges and the encirclement of Soviet forces near the border, but counted on their retreat behind the rivers Daugava and Dnepr as the worst case and saw the most promising focus of attack in the south via Romania.

On September 28, 1940, Keitel ordered the armament of the army by spring 1941 to include 180 field and occupation divisions, for which the army had already made 300,000 skilled workers available to the armaments industry. On October 29, 1940, Paul submitted his memorandum on the "Foundations of the Russian Operation". On November 28, Halder also commissioned the general staffs of the army groups intended for the attack to prepare attack studies for their areas. On November 29, December 3 and 7, 1940, Paulus tried to coordinate these studies and had maneuvers carried out to clarify the distribution of forces and operational goals of the attack against the Soviet Union.

Concerns of individual generals were directed against the target date of the attack, not the war decision. Up until the end of 1940, the OKM in particular tried to give priority to the war against England. The parallel invasion plan was gradually abandoned after the failure of the Battle of Britain in October 1940.

Hitler still kept various approaches open, including the continental bloc idea by Joachim von Ribbentrops . At the beginning of November he hoped, as Halder learned from Kurt von Tippelskirch , "to be able to incorporate Russia into the front against England". On November 4th, however, he demanded that everything should be done “in order to be ready for the big deal” with the Soviet Union, the “problem of Europe” at the regular presentations by the OKW. On November 12, 1940, shortly before the visit of the Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Mikhailovich Molotov to Berlin on the same day, he ordered with his "Instruction No. 18": Regardless of what the outcome of the meeting, the verbally ordered preparations for war against Russia should be continued . Immediately after the meeting he made it clear to the OKW that “the Eastern campaign will begin on May 1, 1941.” In response to Stalin's offer of November 14 not to occupy Finland and to join the three-power pact if Germany recognizes Soviet zones of influence in Bulgaria and Turkey , Hitler did not answer. Days later he told confidants that he was "really relieved" because he had not promised himself anything from the Hitler-Stalin pact, which was not a tenable, honest "marriage of convenience", "because the abysses of worldview are deep enough". He ordered the expansion of command posts in his future headquarters in the east, Wolfsschanze , "in a hurry". According to Keitel's testimony at the Nuremberg Trial in 1945, Hitler considered “the confrontation with Russia to be inevitable at this point in time” for “ideological reasons”. He and other military officials agreed because Hitler had a suggestive persuasive power that was difficult for foreigners to understand, had impressed them with his previous military successes, and they considered him a “genius”.

On December 5, 1940 von Brauchitsch presented the previous operational drafts of war to Hitler. At the same time, Hitler approved the OKH's plan of operations with the war goals presented on July 21. The decision on European hegemony is made in the fight against the Soviet Union. When Halder asked whether the air war against England could then be continued, Hitler declared that the armaments and personnel of the Red Army were inferior to the Wehrmacht. Once struck, this would collapse if large parts of the army were encircled, not driven back. That is why he called for two attack wedges, named the earliest attack time as "mid-May" 1941 and as the target of conquest reaching "around the Volga " in order to use the Luftwaffe to destroy more distant Soviet armaments from there. The Sea Lion company is impracticable. Accordingly, Halder noted as Hitler's order: Otto: Prepare fully in accordance with the principles of our planning. Because of the objections of the OKH, Hitler promised the OKW the following day to strengthen its position permanently. On December 13, 1940 Halder presented Hitler's “situation assessment” of December 5 to the army group leaders and concluded: “The decision on hegemony in Europe will be made in the fight against Russia. Hence preparation when the political situation demands it to face Russia. [...] We are not looking for a conflict with Russia, but we must be ready for this task from the spring of 1941. "

On December 18, 1940, Hitler, as Fuhrer and Supreme Commander of the Wehrmacht, issued Instruction No. 21 pre-formulated by Loßberg :

“The German Wehrmacht must be prepared to overthrow Soviet Russia in a quick campaign even before the end of the war against England (Barbarossa case). […] Preparations that require a longer start-up period should be tackled now - if they have not already been done - and completed by May 15, 1941. However, it is crucial to ensure that the intention of an attack is not recognizable. [...] The ultimate goal of the operation is the shield against Asiatic Russia from the general line Volga - Arkhangelsk . "

For secrecy, all internal orders should be formulated as “precautionary measures [...] in the event that Russia should change its previous attitude towards us”, and as few officers as possible should be dealt with concrete, narrowly defined preparatory work as late as possible. However, the Soviet secret service GRU learned of this order and informed Stalin about it on December 29, 1940.

On January 9, 1941, Hitler reaffirmed his decision to go to war with the OKW by stating that the “wise man” Stalin would “not openly oppose Germany”, but would cause increasing problems in the future, since he was inspired by the urge to go west to inherit impoverished Europe I want and know that Hitler's full victory in Europe made his situation more difficult. As the next most important enemy position, the Soviet Union would have to be smashed in accordance with his previous approach. Either the English would then give in or the war against them could be continued under more favorable circumstances. Japan could then fight the USA with all its might and prevent it from entering the war.

Despite this decision, another German-Soviet economic agreement was concluded on January 10, 1941, according to which the Soviet Union supplied Germany with important raw materials such as oil, metal ores and large quantities of grain. On January 16, 1941, Hitler reaffirmed his "decision: to force Russia to the ground as soon as possible" to the OKH, because Stalin would demand more and more and Germany's victory in continental Europe would remain unacceptable for his ideology. Even skeptical generals shared Hitler's assessment of the situation at the time.

Since the date of the attack was still open, some Wehrmacht representatives considered directive No. 21 to be reversible. On January 18, the national defense department asked Jodl whether Hitler wanted to continue the “Operation Barbarossa”. On January 28, after a meeting with Brauchitsch, Halder noted: “Barbarossa: Meaning not clear. We won't meet the Englishman. Our economic basis is not getting much better. ”On February 3, however, Halder Hitler presented his deployment instructions as a result of directive No. 21 without giving any reservations.

Planning as a war of annihilation

On February 26, 1941, at a meeting with Hermann Göring , Hitler declared that in the coming war it would be crucial “first to finish off the Bolshevik leaders quickly.” With Hitler's order to the OKW of March 3, 1941, the “guidelines on special areas for Revising Directive No. 21, the planning of a war of extermination began . Hitler declared that it was about a battle between two world views, so that a military victory was not enough: "The Jewish-Bolshevik intelligentsia, as the previous oppressor, must be eliminated." “These difficult tasks could not be expected of the army.

Jodl then limited the task of military jurisdiction to criminal matters within the Wehrmacht and planned the use of SS units to murder "Bolshevik chiefs and commissioners" in the army's operational area. On March 5th, all parts of the Wehrmacht received the revised guidelines that the OKW issued unchanged on March 13th. The aim was to divide the western USSR into three satellite states, organized as egalitarian " national communities ", dominated by German " Reich Commissioners " who were directly subordinate to Hitler, and police and SS forces subordinate to Reichsführer SS Heinrich Himmler with "special tasks of the Führer ”. What was meant, but not expressed, was the murder of Soviet elites in the wake of the front, which the perpetrators carried out independently, without the control of the OKW and OKH, and about which they were supposed to report directly to Hitler. Whether and to what extent the army should participate in this remained open. Criticism from the Wehrmacht of these guidelines is not documented, although it was made against the SS during the attack on Poland. This time the OKH saw the SS as support in pacifying the conquered areas, since their own security divisions were considered to be too weak and as many army units as possible were needed for fighting.

On March 17, Hitler repeated to the OKH: The intelligentsia deployed by Stalin should be destroyed, the functionaries should be eliminated. This would require “most brutal violence”, since the Russian people would “tear up” without ideological leadership. Halder knew the opposite assessment by the German embassy in Moscow , that the Russian people and the Red Army would unite nationally and socially in the event of an attack. But he did not contradict Hitler. On March 27th, Brauchitsch told the commanders in chief of the Eastern Army that all soldiers had to be clear, "that the fight will be carried out from race to race, and proceed with the necessary severity."

On March 30, Hitler presented his ideological war aims to 250 generals and senior officers of the Wehrmacht, many of whom had witnessed the end of the First World War as officers and shared the anti-Semitic version of the stab in the back. The forthcoming “ideological battle” is about the “extermination of communism for all time” through the “annihilation of the Bolshevik commissioners and communist intelligentsia”. There was no contradiction. This was followed by other leadership decrees, which the OKW implemented in operational orders and guidelines, including the most important:

- the " Decree on the exercise of martial law in the 'Barbarossa' 'area " of May 13, 1941,

- the "Guidelines for the Conduct of the Troops in Russia" of May 19, 1941.

- the "Guidelines for the Treatment of Political Commissars" ( Commissar Order) of June 6, 1941,

- Hitler's special order to Himmler to murder the "Jewish-Bolshevik" sections of the population behind the front by SD and SS Einsatzgruppen,

- Instructions for the treatment of future Soviet prisoners of war.

During the implementation, the OKW and OKH issued their own instructions that put the soldiers in the mood for murder tasks. On May 6, Halder wrote in his diary about the discussion of the commissioner's order in the OKH: “Troops must fight the ideological struggle with the Eastern campaign”. The general staffs and intelligence officers were prepared for their cooperation with the SD and SS Einsatzgruppen with special courses, as some of the criminal orders could only be passed on orally. The "Eastern Campaign" was prepared as a war of annihilation right down to the material equipment.

The starvation of millions of people was also factored in for economic reasons (see Hunger Plan and General Plan East ). In the "ideas of the specialist military [...] even the extermination of parts of the enemy for economic reasons was legitimate." State secretaries on May 2, 1941 succinctly stated as the "result of the discussion with the business generals" that "undoubtedly tens of millions of people will starve to death if we get what we need out of the country."

The Balkan campaign of April 1941, decided at short notice , was intended to rule out a possible allied southern front that would have endangered “Operation Barbarossa”. For this purpose, the attack date originally planned for May 15, 1941 was postponed. After issuing the extermination orders and completing the military preparations, Hitler ordered the surprise attack on the Soviet Union on June 20, 1941 for June 22.

Historical classification

The Nazi research is particularly pursued this plan of attack intensively to its background, the causes and motives for Hitler's war decision, the war aims, the ratio of the Wehrmacht and the Nazi regime in war planning and mass crimes to determine their failure in more detail as well as the causes and factors.

Particularly controversial was the question of whether Hitler's decision to go to war should rather implement the National Socialist ideology or rather react to the political-military situation at the time. In connection with this, it was also discussed when this decision was finally made. Donald Cameron Watt, for example, put forward the thesis in 1976 that because of the unyielding British attitude in the summer of 1940, Hitler could either only surrender or open the war against the Soviet Union. Robert Cecil interpreted Hitler's decision to go to war in 1976 as a return to his program of 1925, which he had justified against the generals of the Wehrmacht as a military strategy . According to Bernd Stegemann (1979), Hitler wanted to destroy the Soviet Union because Great Britain could use it as a continental war partner ("continental sword") against Germany and Japan.

Andreas Hillgruber , Hugh Trevor-Roper , Eberhard Jäckel , Gerd R. Ueberschär and others stressed, however, that Hitler had sought the joint annihilation of Judaism and communism as a main political goal since the 1920s. The "Operation Barbarossa" was "Hitler's war" with which he wanted to consistently achieve his goals. According to Hillgruber, this annihilation was also intended to enable a later German victory over Great Britain and the USA and thus world domination. The decision to go to war did not come about because of, but despite the impending two-front war, and thus out of political will, not military predicament.

The thesis of "Hitler's war" has been criticized many times as being one-sided. Carl Dirks and Karl-Heinz Janßen have been advocating a counter-thesis since 1997, according to which the OKH had planned a blitzkrieg to destroy the Red Army and conquer large parts of the Soviet Union in late summer 1940 without Hitler's orders or knowledge, prepared with secret troop transfers and Hitler with them urged this fait accompli to war. The Canadian historian Benoît Lemay adopted this thesis without criticizing the source. German historians, on the other hand, paid little attention to them. The military historian Klaus Jochen Arnold rejected them as not covered by Nazi documents and as a conspiracy theory . The Halder biographer Christian Hartmann had documented Halder's knowledge of Hitler's war intentions and the distance to his decision to go to war in 1991.

Rolf-Dieter Müller, on the other hand, used a source-critical analysis of Halder's diary entries to show that Hitler's decision of July 31, 1940 to attack the USSR in the spring of 1941 had already preceded Halder's initiatives in this direction. According to this, Halder tried to come up with a corresponding plan as early as June 1940 "hurriedly". After the Second World War, both Halder and his former adjutant and “Barbarossa” co-planner Reinhard Gehlen , now head of the Federal Intelligence Service, as well as Halder's head of the operations department, Adolf Heusinger , under Konrad Adenauer General Inspector of the Bundeswehr, tried to “Hitler as To portray sole culprits for the Eastern War and the failure of a supposedly ingenious campaign plan. "

The reason for such a campaign, however, was not because the Germans perceived the USSR as a “threat”, but rather because Hitler wanted to wage a war for “living space in the east”. For this purpose, the neighboring state of Poland had been courted by the German leadership since 1934, in the hope of being able to persuade it to take joint military action against the USSR, or at least to take a neutral stance while simultaneously leaving Gdańsk and a corridor for deployment, Passage and supply area for a war "in the east". The Polish side was given the prospect of gaining parts of Ukraine for this purpose. But when Poland finally turned away from the German Reich and turned to the Western powers France and Great Britain in March 1939, the option of attacking the Soviet Union after Poland was overthrown was still haunted in the minds of the German war planners. The declarations of war by France and Great Britain made this option obsolete and led to the course of events that ultimately became manifest history.

In connection with Müller's analysis, critics emphasize above all that “he provides an analysis of the real war plans that is not constrained into any corset of intentionalist or functionalist metatheories” and “on the basis of a critical source analysis the actual responsibility of Halder, Heusinger and Gehlen with their counterfactual justifications after 1945 [contrasts] ". Furthermore, “Müller can prove that [on the part of Germany] in no phase of the military planning [between] 1938 [and] 1941 did the fear of an allegedly threatened attack by the Red Army play a role. On the contrary, they assumed their weakness and a victory that could be achieved in a few weeks. "

literature

Documents

- Barbarossa case. Documents for the preparation of the fascist armed forces for the aggression against the Soviet Union (1940/41). Selected and introduced by Erhard Moritz. Military publishing house of the German Democratic Republic , Berlin 1970.

- Walther Hubatsch (ed.): Hitler's instructions for warfare 1939–1945. Documents of the High Command of the Wehrmacht. 2nd Edition. Bernard & Graefe, Frankfurt am Main 1983, ISBN 3-7637-5247-1 .

Historical representations

- Albert Beer: The Barbarossa case: investigation into the history of the preparations for the German campaign against the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics in 1941. Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität, Münster 1979.

- Horst Boog, Jürgen Förster, Joachim Hoffmann , Ernst Klink, Rolf-Dieter Müller , Gerd R. Ueberschär : The attack on the Soviet Union (= Military History Research Office [ed.]: The German Reich and the Second World War . Volume 4 ). 2nd Edition. Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Stuttgart 1987, ISBN 3-421-06098-3 .

- Gerd R. Ueberschär , Wolfram Wette (ed.): The German attack on the Soviet Union. “Enterprise Barbarossa” 1941. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 1991, ISBN 3-596-24437-4 .

- Bernd Wegner (Ed.): Two ways to Moscow. From the Hitler-Stalin Pact to Operation Barbarossa. Piper, Munich / Zurich 1991, ISBN 3-492-11346-X .

- Roland G. Foerster (Ed.): "Operation Barbarossa". On the historical site of German-Soviet relations from 1933 to autumn 1941. Oldenbourg, Munich 1999, ISBN 3-486-55979-6 .

- Erich later: The third world war. The Eastern Front 1941–1945. Conte, St. Ingbert 2015, ISBN 978-3-95602-053-7 .

- Klaus Jochen Arnold: The Wehrmacht and the Occupation Policy in the Occupied Territories of the Soviet Union: Warfare and Radicalization in "Operation Barbarossa". Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 2005, ISBN 3-428-11302-0 .

- Wolfgang Fleischer: Company Barbarossa 1941. Dörfler, Eggolsheim 2007, ISBN 978-3-89555-488-9 .

- Christian Hartmann : Wehrmacht in the Eastern War: Front and military hinterland 1941/42. 2nd Edition. Oldenbourg, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-486-70225-5 .

- Christian Hartmann: Company Barbarossa. The German War in the East 1941–1945. Beck, Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-406-61226-8 .

- Michael Brettin, Peter Kroh, Frank Schumann (eds.): The Barbarossa case. The war against the Soviet Union in unknown images. Das Neue Berlin, Berlin 2011, ISBN 978-3-360-02128-1 .

- Rolf-Dieter Müller : The enemy is in the east. Hitler's secret plans for a war against the Soviet Union in 1939. Ch. Links Verlag, Berlin 2011, ISBN 978-3-86153-617-8 .

Web links

- German Historical Museum: Assault on the Soviet Union

- Edition Barbarossa from the Historisches Centrum Hagen

- Karl-Heinz Janssen : Plan Otto. (Die Zeit No. 38/97 of September 12, 1997; Chief of the General Staff Halder had already for the late summer of 1940, without Hitler's knowledge ... ) Company_Barbarossa

- Barbarossa company at Shoa.de

- Gert Carsten Lübbers: Wehrmacht and economic planning for the company "Barbarossa" ; Diss. At the University of Münster ( memo from November 26, 2011 on WebCite )

- Directive No. 21 "Barbarossa case", December 18, 1940 , in: 1000dokumente.de . With an introduction by Johannes Hürter

- Torsten Diedrich : Friedrich Paulus, the "Operation Barbarossa" and the myth of preventive war . Lecture at the Center for Military History and Social Sciences of the Bundeswehr in Potsdam, June 15, 2016.

Individual evidence

- ^ Gerhard Schreiber, Bernd Stegemann, Detlef Vogel: Germany and the Second World War. Volume 3. Clarenson Press, Oxford 1995, ISBN 0-19-822884-8 , p. 216, fn. 168.

- ^ Erwin A. Schmidl: The "Anschluss" of Austria. Bernard & Graefe, 1994, ISBN 3-7637-5936-0 , p. 32 ff.

- ↑ Norbert Schausberger: The grip on Austria. The connection. Vienna-Munich 1978, p. 398 f .; here especially p. 401. Manfred Messerschmidt : Foreign policy and war preparation. In: Military History Research Office . (Ed.): The German Reich and the Second World War , Volume 1: Causes and requirements of German war policy. Stuttgart 1979, p. 636 f.

- ↑ See e.g. BG Koch, A. Philipp: Handbook for history lessons. Quelle & Meyer Verlag, Leipzig ²1921; Heinrich Claß : German History (1909) 18th edition. 1939, p. 23; Richard Suchwirth : German history: From the Germanic prehistory to the present. Georg Dollheimer Verlag, Leipzig 1934 (new editions until 1942).

- ^ Albert Brackmann: Crisis and construction in Eastern Europe. A picture of world history. Berlin-Dahlem (Ahnenerbe-Stiftung Verlag) 1939, pp. 16-19; Text online ; PDF; 417 kB.

- ↑ on the symbolic political background: Michael Burleigh: Germany turns eastwards. A study of 'Ostforschung' in the Third Reich. London (Pan Books) 2002, ISBN 0-330-48840-6 ; especially pp. 134-137 and p. 321 (quotation from Aubin).

- ↑ June 19, 1940: Gerhard Schreiber: The Second World War. 4th unchanged edition. CH Beck, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-406-44764-8 , p. 36; July 3, 1940: Jürgen Förster: Hitler's decision to go to war against the Soviet Union. In: The German Reich and the Second World War Volume 4, Stuttgart 1983, p. 9 f.

- ^ Letter from Loßberg to WE Paulus dated September 7, 1956; see Gerd R. Ueberschär: Hitler's decision to initiate a "living space" war in the east. In: Gerd R. Ueberschär, Wolfram Wette (ed.): The German attack on the Soviet Union - Operation Barbarossa 1941. Fischer Taschenbuch, Frankfurt am Main 1991, ISBN 3-596-24437-4 , p. 106, fn. 126.

- ↑ Arno J. Mayer : The war as a crusade . The German Reich, Hitler's Wehrmacht and the “Final Solution” . Reinbek near Hamburg 1989, p. 340.

- ^ Klaus Jochen Arnold: The Wehrmacht and the Occupation Policy in the Occupied Territories of the Soviet Union: Warfare and Radicalization in "Operation Barbarossa". Berlin 2005, p. 53; Christian Hartmann: Halder. Chief of Staff of Hitler 1938–1942. Schoeningh, Paderborn 1991, p. 233.

- ^ After Andreas Hillgruber: Once again: Hitler's turn against the Soviet Union in 1940. In: History in Science and Education. Ernst Klett Verlag, 33rd year 1982, p. 217.

- ^ Rolf-Dieter Müller : The enemy stands in the east , Berlin 2011, p. 50

- ↑ Federal Archives , NS 11/28; Lecture at Jürgen Förster: Hitler's decision to go to war against the Soviet Union. In: The German Reich and the Second World War, Volume 4, Stuttgart 1983, p. 22.

- ↑ Gerd R. Ueberschär: Hitler's decision to initiate a "living space" war in the east. In: Gerd R. Ueberschär, Wolfram Wette (ed.): The German attack on the Soviet Union - 'Enterprise Barbarossa' 1941. Fischer paperback, Frankfurt am Main 1991, ISBN 3-596-24437-4 , p. 19 f.

- ↑ Jürgen Förster: Hitler's decision to go to war against the Soviet Union. In: The German Reich and the Second World War, Volume 4, Stuttgart 1983, p. 8, fn. 38 and 39.

- ↑ Ulrich von Hassell: Vom Andern Deutschland. From the posthumous diaries 1938–1944. Frankfurt am Main 1964, p. 71.

- ^ Nicolaus von Below: Hitler's adjutant. P. 192.

- ↑ Helmuth Groscurth : Diaries of an Abwehroffiziers 1938-1940 , Stuttgart 1970, p. 385 (October 21, 1939), p. 414 (November 23, 1939).

- ↑ Nicolaus von Below : As Hitler's adjutant. 1937-1945 . Selent 1999, p. 217.

- ↑ Wolfgang Michalka and Gottfried Niedhart : German History 1918-1933 . Frankfurt am Main 2002, p. 132 f.

- ↑ Paul Deichmann : The boss in the background . Oldenburg 1979, p. 66.

- ^ Walter Görlitz : Generalfeldmarschall Keitel criminal or officer? . Göttingen 1961, p. 128.

- ↑ Hans-Erich Volkmann : From Blomberg to Keitel - The Wehrmacht leadership and the dismantling of the rule of law . In: Rolf-Dieter Müller , Hans-Erich Volkmann (ed.): The Wehrmacht. Myth and Reality . Munich 2012, p. 52.

- ↑ Rolf-Dieter Müller : The enemy is in the east. Hitler's secret plans for a war against the Soviet Union in 1939. Ch. Links Verlag, Berlin 2011, p. 125; see also Sven Felix Kellerhoff : Hitler wanted to invade the Soviet Union as early as 1939 , Die Welt, May 18, 2011

- ^ Quoted by Karl Klee: The company "Sea Lion". The planned landing in England in 1940. Musterschmidt, Göttingen 1958, p. 189.

- ↑ Gerd R. Ueberschär: The development of German-Soviet relations. In: The German attack on the Soviet Union 1941. Primus-Verlag, Darmstadt 1998, p. 11 and fn. 39–41.

- ↑ IMT, Volume 28, Document 1759-PS, pp. 238 ff .; quoted by Gerd R. Ueberschär: Hitler's decision on the "Lebensraum" war in the east. In: Gerd R. Ueberschär, Wolfram Wette: "Operation Barbarossa". The German attack on the Soviet Union in 1941. 1984, p. 95 and footnote 62.

- ^ Franz Halder: War diary. Volume 1, p. 107.

- ^ Order printed in: Eduard Wagner: Der Generalquartiermeister. Munich 1963, p. 144 f.

- ^ Franz Halder: War diary. Volume 1, p. 372.

- ^ Franz Halder: War diary. Volume 1, p. 375.

- ↑ Franz Halder: War Diary Volume II, pp. 6 ff. (July 3-4, 1940); Ernst Klink: The military conception of the war against the Soviet Union. In: The German Reich and the Second World War Volume 4, Stuttgart 1983, p. 206 f.

- ^ Hans Pottgiesser: The Deutsche Reichsbahn in the Eastern Campaign 1939-1941. Neckarsgmünd 1960, p. 21 ff.

- ^ Letter from Loßbergs to Friedrich WE Paulus dated September 7, 1956; in the archive of the Institute for Contemporary History in Munich, ZS 97.

- ^ So Alfred Jodl 1945 - Institute for Contemporary History : Alfred Jodl's notes and conversation notes from August 22, 1945 (archive ED 115/5).

- ^ Christian Hartmann: Halder , Paderborn 1991, p. 225.

- ^ General Staff of the Army, Operations Department, instructions for AOK 18 (June 29, 1940): Documents printed by Erhard Moritz: Case Barbarossa. 1970, pp. 226-229; also retrospectively Franz Halder: War Diary Volume 2, p. 443 (June 4, 1941).

- ^ Franz Halder: War diary. Volume 1, p. 360 (June 18, 1940).

- ↑ Christoph Studt: The Third Reich in data. CH Beck Verlag, Munich 2002, ISBN 3-406-47635-X , p. 135.

- ↑ Files on German Foreign Policy (ADAP) D, X, Document 166, p. 172 f.

- ^ Franz Halder: Kriegstagebuch, Volume II, p. 32 (July 22, 1940); lectured by Christian Hartmann: Halder , Paderborn 1991, p. 225.

- ^ Walter Warlimont : In the headquarters of the German Wehrmacht 1939-1945. 2nd Edition. Frankfurt am Main 1963, p. 126 ff .; Referred to by Andreas Hillgruber: Hitler's strategy , 1982, p. 222.

- ^ Michael Salewski : The German Naval Warfare 1935-1945. Volume III: Memoranda and Considerations of the Situation 1938–1944. Frankfurt am Main 1973, p. 140.

- ^ Walter Warlimont : In the headquarters of the German Wehrmacht 1939-1945. Weltbild Verlag GmbH, Augsburg 1990, p. 126.

- ^ Christian Hartmann: Halder. Paderborn 1991, p. 227 f.

- ^ Wilhelm Keitel (Chief of the Wehrmacht High Command), Alfred Jodl (Chief of the Wehrmacht Command Staff), Walther von Brauchitsch (Commander-in-Chief of the Army), Erich Raeder (Commander-in-Chief of the Navy), Franz Halder (Chief of Staff). Goering (Commander in Chief Air Force) was not present. Cf. Antony Beevor: The Second World War. Munich 2014, p. 156.

- ^ Franz Halder: War Diary Volume II, pp. 46–49 (July 31, 1940); lectured by Christian Hartmann: Halder , Paderborn 1991, p. 225 ff.

- ↑ Bernd Wegner: Hitler's War? For the decision, planning and implementation of the "Barbarossa Company". In: Christian Hartmann and others (ed.): Crimes of the Wehrmacht. Balance of a debate. Beck, Munich 2005, ISBN 3-406-52802-3 , p. 35 f.

- ↑ For Hitler's bundle of motifs, see Andreas Hillgruber: Hitler's strategy. Politics and Warfare, 1940–1941. 2nd Edition. Bernard & Graefe Verlag für Wehrwesen, Frankfurt am Main 1982, p. 223 ff .; Jürgen Förster: Hitler's turn to the east. German war policy 1940–1941. In: Bernd Wegner (Ed.): Two ways to Moscow. From the Hitler-Stalin Pact to "Operation Barbarossa". Piper, Munich / Zurich 1991, pp. 113-123.

- ^ Andreas Hillgruber: Company "Barbarossa". In: Andreas Hillgruber (Ed.): Problems of the Second World War. 2nd expanded edition. Kiepenheuer & Witsch, Cologne / Berlin 1986, ISBN 3-445-01689-5 , p. 105 ff.

- ^ Christian Hartmann : Halder Chief of Staff of Hitler . Paderborn 1991, p. 267.

- ↑ Percy Ernst Schramm (Ed.): War diary of the High Command of the Wehrmacht . Bonn undated, Volume 1, 1st half volume, p. 258. Quoted from Dietrich Eichholtz : History of the German War Economy . Berlin 1985, volume 2, p. 3.

- ^ Dietrich Eichholtz : History of the German war economy . Berlin 1985, Volume 2, p. 16.

- ^ Heinrich Uhlig: The influence of Hitler on the planning and leadership of the Eastern campaign. In: Heinrich Uhlig: Power of Conscience. Volume 2, Rinn, Munich 1965, p. 168, fn. 29.

- ^ Wilhelm Deist: The military planning of "Operation Barbarossa" , in: Roland G. Foerster (Ed.): "Operation Barbarossa": On the historical location of German-Soviet relations from 1933 to autumn 1941. ( Contributions to military history, vol. 40 ), Oldenbourg, 1993, pp. 109-122, here p. 118.

- ^ War diary of the OKW, Volume 1, p. 968 f .; Gerhard L. Weinberg: The German decision to attack the Soviet Union. In: VfZ 1.4 (1953), p. 314 ff.

- ^ War diary of the OKW, Volume 1, p. 3 ff.

- ↑ Ingo Lachnit, Friedhelm Klein: The Operation Draft East of Major General Marcks from August 5, 1940. In: Wehrforschung Heft 4/1972, pp. 114–123.

- ↑ Erhard Moritz: Barbarossa case. Berlin 1970, pp. 200-205.

- ^ Franz Halder: War Diary, Volume II, pp. 90 and 98.

- ↑ IMT, Volume 27, p. 72 f.

- ^ Ralf Georg Reuth: Joseph Goebbels - Diaries 1924-1945. 3. Edition. Piper Verlag, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-492-21414-2 , Volume 4, p. 1463 (August 9, 1940).

- ↑ Ernst Klink: The military conception of the war against the Soviet Union. In: The German Reich and the Second World War Volume 4, Stuttgart 1983, p. 202.

- ^ Franz Halder: Kriegstagebuch II, p. 78 f. (August 26/27, 1940).

- ^ Hermann Teske: General Ernst Köstring - The military mediator between the German Reich and the Soviet Union 1921-1941. 1965, p. 281 ff.

- ↑ Ernst Klink: The military conception of the war against the Soviet Union. In: MGFA (ed.): The attack on the Soviet Union (= Volume 4 of The German Reich and the Second World War ), 1983, pp. 230-233.

- ↑ Franz Halder, Kriegstagebuch II, p. 158 ff. (November 1-2, 1940).

- ^ Franz Halder: War Diary Volume II, p. 165 (November 4, 1940).

- ↑ Walther Hubatsch: Hitler's instructions for warfare 1939–1945. Nebel Verlag, 1999, ISBN 3-89555-173-2 , p. 71.

- ^ War diary of the OKW, Volume 1, p. 176.

- ^ Jürgen Förster: Hitler's turn to the east. In: Bernd Wegner: Two ways to Moscow. P. 122 f.

- ↑ Hildegard von Kotze (ed.): Heeresadjutant bei Hitler 1938–1943. Notes of Major Engel (1974), Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Stuttgart 1982, ISBN 3-421-01699-2 , p. 91 f.

- ↑ Walter Görlitz (Ed.): Generalfeldmarschall Keitel. Criminal or officer? Memories, letters, documents from the OKW. (1961) Bublies, 1998, ISBN 3-926584-47-5 , p. 392.

- ^ War diary of the OKW. Volume 1, pp. 203 ff. (December 5, 1940).

- ^ Franz Halder: War diary. Volume 2, p. 211 (December 5, 1940).

- ^ War diary of the OKW. Volume 1, pp. 214 f. (December 6, 1940).

- ^ Franz Halder: War diary. II, pp. 224-228 (December 13, 1940).

- ^ NS archives: Directive No. 21: Barbarossa case

- ↑ Lev A. Bezymenski: The Soviet intelligence service and the beginning of the war of 1941. In: Gerd R. Ueberschär, Lev A. Bezymenskij (ed.): The German attack on the Soviet Union in 1941. The controversy surrounding the preventive war thesis. 2nd Edition. 2011, p. 106.

- ^ War diary of the OKW, Volume I / 1, p. 257 (January 9, 1941).

- ^ Franz Halder: Kriegstagebuch II, p. 244 (January 16, 1941).

- ^ OKW / Wehrmacht command staff, Annex to Hitler's remarks, January 20, 1941; in: IMT, Volume 34, Document 134-C, p. 467.

- ^ War diary of the OKW, Volume I / 1, p. 269 (January 18, 1941).

- ^ Franz Halder: War Diary Volume 2, p. 261.

- ^ Franz Halder: War Diary, Volume 2, p. 463 ff.

- ^ Jürgen Förster: The company "Barbarossa" as a war of conquest and annihilation. In: MGFA Volume 4, p. 414 f.

- ↑ Jürgen Förster : On the image of Russia by the military 1941-1945 . In: Hans-Erich Volkmann (ed.): The image of Russia in the Third Reich . Cologne 1994, p. 146.

- ↑ Felix Römer : “In old Germany such an order would not have been possible.” Reception, adaptation and implementation of the Martial Law Decree in the Eastern Army 1941/42 Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte 2008, pp. 53–99.

- ^ Hans-Adolf Jacobson: Commissar order and mass executions of Soviet prisoners of war. In: Martin Broszat et al. (Ed.): Anatomy of the SS State. Volume 2, Munich 1967, pp. 135-232.

- ^ Franz Halder: War Diary, Volume 2, p. 399.

- ↑ Gerd R. Ueberschär: Hitler's decision to initiate a "living space" war in the east. In: Gerd R. Ueberschär, Wolfram Wette (ed.): The German attack on the Soviet Union - 'Enterprise Barbarossa' 1941. Frankfurt am Main 1991, p. 110 ff.

- ^ Rolf-Dieter Müller : The Second World War 1939-1945. Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 2004, p. 127.

- ^ Rolf-Dieter Müller: The Second World War 1939-1945. P. 128; Alex J. Kay : Starving as a Strategy for Mass Murder. The meeting of the German state secretaries on May 2, 1941. In: Zeitschrift für Weltgeschichte . Edited by Hans-Heinrich Nolte . Vol. 11, issue 1/2010, pp. 81-105.

- ↑ Klaus Hildebrand: The Third Reich. 7th, through Edition. Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag, 2009, ISBN 978-3-486-59200-9 , p. 76.

- ↑ Gerd R. Ueberschär: The military planning for the attack on the Soviet Union. In: Gerd R. Ueberschär, Lev A. Bezymenskij (ed.): The German attack on the Soviet Union in 1941. The controversy over the preventive war thesis . 2nd Edition. Primus-Verlag, Darmstadt 2011, ISBN 978-3-89678-776-7 , p. 31.

- ↑ Overview: Rolf-Dieter Müller (author), Gerd R. Ueberschär: Hitler's War in the East 1941–1945: A research report. Adult and completely revised Reissue. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 2000, ISBN 3-534-14768-5 .

- ↑ DC Watt: The Times Literary Supplement , No. 3879, July 16, 1976 (review).

- ^ Robert Cecil: Hitler's decision to invade Russia, 1941. 1st edition. David McKay Company, New York 1976, ISBN 0-679-50715-9 .

- ↑ Klaus A. Maier and others, MGFA (ed.): The establishment of hegemony on the European continent. Volume 2 of The German Reich and the Second World War. Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Stuttgart 1991, ISBN 3-421-01935-5 , p. 33.

- ^ Hugh Trevor-Roper: Hitler's War Aims. In: Hans-Adolf Jacobsen: National Socialist Foreign Policy 1933 to 1938. Luchterhand Verlag GmbH, 1968, ISBN 3-472-65039-7 , p. 132 ff.

- ^ Andreas Hillgruber: Hitler's Strategy: Politics and Warfare, 1940-1941 (1965), 3rd edition. Bernard & Graefe, 1993, ISBN 3-7637-5923-9 ; Positions summarized by Jürgen Förster: Hitler's decision to go to war against the Soviet Union. In: The German Reich and the Second World War Volume 4, Stuttgart 1983, p. 18.

- ↑ Examples: Ulrike Hörster-Philipps, Reinhard Kühnl (ed.): Hitler's War? On the controversy about the causes and character of the Second World War. Pahl-Rugenstein, Cologne 1990, ISBN 3-7609-1308-3 ; Christoph Kleßmann (Ed.): Not just Hitler's war. The Second World War and the Germans. Droste, 1989, ISBN 3-7700-0795-6 .

- ↑ Carl Dirks, Karl-Heinz Janßen: The war of the generals. Hitler as a tool of the Wehrmacht. 3. Edition. Propylaeen, Berlin 1999, pp. 135 f. And more often; Karl Heinz Janßen: "Plan Otto". In: The time. 38/1997.

- ↑ Benoît Lemay: La guerre des généraux de la Wehrmacht: Hitler au service des ambitions de ses élites militaires? Reprinted from Guerres mondiales et conflits contemporains 4/2005, No. 220, pp. 85-96.

- ↑ Klaus-Jochen Arnold: Review of the war of the generals. In: MGFA (Ed.): Military History Journal . (MGZ) Vol. 59 (2000), Issue 1, pp. 240-243.

- ^ Christian Hartmann: Halder. Paderborn 1991, p. 227 f.

- ↑ Rolf-Dieter Müller: The enemy is in the east. Hitler's secret plans for a war against the Soviet Union in 1939. Ch. Links Verlag, Berlin 2011, p. 208.

- ↑ Rolf-Dieter Müller: The enemy is in the east. Hitler's secret plans for a war against the Soviet Union in 1939. Ch. Links Verlag, Berlin 2011, p. 261.

- ↑ See Rolf-Dieter Müller: The enemy is in the east. Hitler's secret plans for a war against the Soviet Union in 1939. Ch. Links Verlag, Berlin 2011, pp. 45–68, 106–122, 251–261.

- ↑ Wigbert Benz: Review of: Müller, Rolf-Dieter: The enemy stands in the east. Hitler's secret plans for a war against the Soviet Union in 1939. Berlin 2011 . In: H-Soz-Kult, August 5, 2011, accessed on May 15, 2016.