Reinhard Gehlen

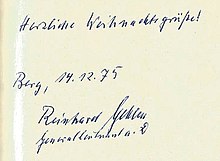

Reinhard Gehlen (born April 3, 1902 in Erfurt , † June 8, 1979 in Berg am Starnberger See), as major general of the Wehrmacht, headed the Foreign Armies East Department (FHO) in the Army General Staff . After the Second World War , with the consent of the American occupying forces, he set up a foreign intelligence service, the Gehlen organization , which was taken over by the federal government in 1955 and converted into the Federal Intelligence Service (BND) in 1956 . He headed this agency from 1956 to 1968.

Life

origin

Reinhard Gehlen was born into a middle-class family in Erfurt. His father Walther (1871–1943) was Major a. D. the artillery and from 1908 bookseller in Breslau , where Reinhard grew up. Walther Gehlen was most recently director of the Ferdinand Hirt publishing house in Breslau, which he had taken over from his brother Max Gehlen. His mother Katharina van Vaernewyk (1878–1922) came from Flanders . Reinhard Gehlen was a cousin of the influential sociologist Arnold Gehlen .

Military background

Reichswehr

Promotions

- 1st December 1923 lieutenant

- 1st February 1928 first lieutenant

- May 1, 1934 Captain

After graduating from the humanistic König-Wilhelm-Gymnasium in Breslau, Gehlen entered the 6th light artillery regiment of the Reichswehr in Schweidnitz as an officer candidate on April 20, 1920 . In October of the same year he was transferred to the 3rd Artillery Regiment. From September 1926 to October 1928 he was transferred to the Hanover Cavalry School due to his skills as a rider and graduated with the rank of first lieutenant . From November 1928 to March 1929 he was transferred to Staff V. (riding) / Artillery Regiment 3. From April 1929 to September 1933 he was a battalion adjutant of the 1st / 3rd Artillery Regiment; in October he was transferred to the 14th / 3rd Artillery Regiment.

Wehrmacht

General

From October 1933 to July 1935 he was employed by the Chief of the Army Command, General of the Infantry Kurt von Hammerstein-Equord , and commanded the secret general staff courses . In May 1935 he was assigned to the War Academy . From July 1935 to July 1936 he was adjutant to Oberquartiermeister I in the Army General Staff in the Reich Ministry of War in Berlin. In July 1936 he was transferred to the 1st Department and in July 1937 to the 10th Department of the General Staff of the Army. At that time he was under Major General Erich von Manstein .

From November 1938 to August 1939 he was battery chief ( field howitzers ) of the 8th / Artillery Regiment 18 in Liegnitz . In August 1939 he became First General Staff Officer (Ia) of the 213rd Infantry Division and took part in the attack on Poland . From October 1939 to May 1940 he was the group leader responsible for the fortifications in the Army General Staff. From May to June 1940 he was a liaison officer of the Army High Command to the 16th Army and to the Hoth and Guderian Panzer Groups . In June 1940 he became 1st adjutant to Chief of Staff Franz Halder . From October 1940 to April 1942 he was head of the Eastern group of the operations department of the Army General Staff, which was headed by Colonel i. G. Adolf Heusinger (later General Inspector of the Bundeswehr ) was headed.

Gehlen was involved in the preparations for Operation Barbarossa , the attack on the Soviet Union in June 1941; he was in particular responsible for planning transport and reserve tracking. After the setbacks on the Eastern Front in the winter of 1941/42 ( Battle of Moscow ), the General Staff looked for new leadership for its Army Intelligence Service , which competed with the Reich Security Main Office . Although Gehlen had never engaged in secret service work, spoke no foreign language and had no knowledge of the Soviet Union, he was appointed head of the " Foreign Army East Department " in May 1942 and was thus also head of the East German intelligence and, above all, its evaluation. At first he was also responsible for Scandinavia, Southern Europe and the air armament of the USA .

Foreign Armies Department East

Promotions

- June 1, 1938 Major i. G.

- July 1, 1941 Lieutenant Colonel i. G.

- July 1, 1942 Colonel i. G.

- December 1, 1944 Major General

He quickly rebuilt his office, which originally evaluated information from the head of the Abwehr Admiral Wilhelm Canaris . It was able to evaluate messages in an integrated manner without having to involve other departments. Gehlen also got information through drastic mass surveys of prisoners of war according to the motto of the high command of the army : "Any forbearance and humanity towards the prisoners of war is to be censured severely." Gehlen put Heinz Herre for the evaluation, Gerhard Wessel for the reconnaissance of the Red Army and Hermann Baun for the agent network in enemy territory in front of the front. He took these three over to the Gehlen Organization in 1946 after the war .

After the defeat of Stalingrad in the winter 1942/1943 Gehlen worked with the foreign intelligence service of the SS under the direction of Walter Schellenberg together. Together with Soviet prisoners of war, defectors and anti-communists in 1943 in the Soviet Union, both wanted to set up a force under General Vlasov as a committee for the liberation of the peoples of Russia not only to set up combat units but also to educate. Involved in this change in strategic and operational reconnaissance from the Abwehr to the SS was - after taking over the hunting associations from the Brandenburg division - their new commander, Otto Skorzeny .

During the reconnaissance of the Soviet forces in the area of Army Group Center , the 6th Guards Army and the 5th Guards Panzer Army remained undetected until the beginning of the Soviet Bagration Operation , the Foreign Armies Department for their evaluation and situation assessment as well as assessment of the situation East under Gehlen was responsible.

Gehlen also suggested the "werewolf campaign", a resistance from earth depots. To date there are only a few scientifically founded analyzes of the work of Fremde Heere Ost .

From October 1944, Gehlen planned for the time after the war. For this he developed a hypothesis that later proved to be correct: “The Western powers will turn against their ally Russia. They will need me, my employees and my copied documents in the fight against communist expansion because they have no agents there themselves. "

End of war and captivity

At the beginning of March 1945, just in time for the end of the war, Gehlen had all of the intelligence material reproduced on microfilm by a handpicked team and, packed in watertight barrels, buried in several mountain meadows in the Austrian Alps.

Gehlen had previously sent his family from Liegnitz to the Bavarian Forest via Naumburg so that they would not fall into the hands of the Red Army. With his colleagues Wessel and Baun he signed the "Pact of Bad Elster ". They arranged an orderly handover to the Americans.

On April 9, 1945, Hitler dismissed Gehlen; Gerhard Wessel became his successor , as he did later with the BND in 1968 . Finally, on April 28, Gehlen left the headquarters of the Wehrmacht in Bad Reichenhall , hid on the Elendsalm near Miesbach and, together with six officers, surrendered to soldiers of the 7th US Army in Fischhausen am Schliersee on May 22, 1945 .

Gehlen had to ensure that he was not extradited to the Soviet Union for his actions on the Eastern Front, as agreed between the Allies. That is why Gehlen tried to explain to the Americans who interrogated him the importance of his person for the post-war period. However, they initially met with little interest. Via Wörgl and Salzburg he reached the Villa Pagenstecher in Wiesbaden for questioning . There he was questioned by General Edwin L. Sibert (1897–1977). In conversation it turned out that both had very similar visions about the role of the Americans in the future. The document boxes hidden by Gehlen were dug up and brought to the document center in Höchst . Captain Boker collected Gehlen's important comrades-in-arms and evaded them from imprisonment.

Gehlen, who was a prisoner of war with the US Army Air Forces , was finally flown in 1945 with six former employees and the documents by the United States Department of War to the USA to Fort Hunt , Virginia near Washington, DC . As in the Gehlen case, the Allies initially also took other experts into custody, including the rocket researcher Wernher von Braun and the nuclear physicists working with Otto Hahn .

Building a secret service

Organization Gehlen

Nothing is known precisely about the process and the result of the interrogation in the USA. Around 3000 documents from the National Archives on Gehlen for the period 1945 to 1955 were made accessible in 2000–2002. So far, however, there has been no historically sound evaluation. Gehlen was brought back from Fort Hunt to Camp King near Oberursel in June 1946 . In July 1946 the US Army Intelligence Service G-2 Section founded the later organization Gehlen , initially financed by the USA , of which he became head at the end of 1946. The working basis was the following oral agreement:

- A German intelligence service organization will be created using the existing potential, which will clear up eastwards or continue the old work in the same way. The basis is the common interest in defense against communism.

- The German organization does not work for or among the Americans, but with the Americans.

- The organization works under exclusive German leadership, which receives its tasks from the American side, as long as there is no German government in Germany.

- The organization is funded by the American side ... In return, it delivers all the educational results to the Americans.

- As soon as there is a sovereign German government again, it is up to this government to decide whether or not the work should continue ...

- Should the organization ever be faced with a situation in which the American and German interests diverge, the organization is free to follow the line of German interests.

The tendency of this text is reminiscent of the Himmeroder memorandum . Adolf Heusinger , Hans Speidel and Hermann Foertsch were also involved in creating it in 1950 .

From December 6, 1947 (code name Nikolaus), the organization was housed in the former " Reichssiedlung Rudolf Hess " in Heilmannstrasse in Pullach , because the camp was too small and the obligation to maintain secrecy there was built from 1936 to 1938 for the Nazi elite A village with initially 20 houses behind high walls was better to guarantee. From July 1, 1949, the anti-communist CIA took over the Gehlen organization. The Gehlen organization performed a double function for the CIA and the still young Federal Republic of Germany . It was structured in a similar way to its predecessor, Fremde Heere Ost : management by Gehlen, Gerhard Wessel for the evaluation and Hermann Baun responsible for a network of agents. They also used their tried and tested methods: prisoners of war, former forced laborers and refugees were systematically questioned in reception camps.

Reinhard Gehlen himself understood his organization from the start as a preliminary form of an independent German intelligence service. Konrad Adenauer was not given much choice by the Allies when it came to calling up his own security apparatus. It was therefore clear to him that a completely independent West German foreign intelligence service was just as unthinkable as an independent West German army. So he accepted the transformation of the Gehlen Organization, in which a number of former Wehrmacht officers , RSHA and SS members were “parked” as personnel reserves. Gehlen hid her identity to protect her from access by the Allies and to make denazification more difficult. On the “recommendation” of the British, Adenauer appointed the former general of the armored troop Gerhard Graf von Schwerin as his “advisor on security issues”. He founded a kind of intelligence service with the code name " Zentrale für Heimatdienst ", which was staffed with Joachim Oster and Friedrich Wilhelm Heinz as prominent figures from the former Abwehr . In contrast to Gehlen, Heinz had good contacts with the French occupying power . Gehlen was finally able to get through Adenauer's State Secretary Hans Globke that Heinz was put on leave on October 1, 1953 and released shortly afterwards.

After the beginning of the Korean War on June 20, 1950, Gehlen intensified contact with the Adenauer government and the SPD opposition. Through his employees Heusinger , Speidel and Foertsch he intervened in the rearmament planning . In the first ten years after the end of the war, Gehlen knew how to quickly build up a professional intelligence service by recruiting many secret service agents with a dubious Nazi past, such as Heinz Felfe . But this was also riddled with potential traitors precisely because of this burden. Hundreds of agents, radio codes and communication channels were revealed. But in view of the numerous "moles" in the British secret service, this was not a Gehlen-specific phenomenon. Gehlen knew how to outmaneuver his rivals for Gerhard Graf von Schwerin in Bonn as a foreign secret service, just as he succeeded in restricting the Military Counterintelligence Service (MAD) to counter-espionage within the Bundeswehr and the security check of its personnel. There were also arguments with Otto John , the first head of the Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution . John's transfer to East Berlin in 1954, the circumstances of which have not yet been fully clarified, commented Gehlen, who had an "aversion to anti-Hitler emigrants" (Der Spiegel), with "Once a traitor, always a traitor!" Connection with John's participation in the resistance against National Socialism.

Gehlen was not inept at getting approval for his intelligence service from all political camps. His tendency to surround himself with the aura of the opaque, enigmatic and mysterious played a role, as did his interaction with the news magazine Der Spiegel , with which he was in close contact. This was also due not least to the fact that former Wehrmacht officers were working there in the early 1950s.

Foundation of the Federal Intelligence Service

As early as 1951, the discussion about the establishment of one or more intelligence services at the federal level began. According to a report by the Central Intelligence Agency , the name Bundesnachrichtendienst (BND) was first used in conversations in the Chancellery in August and September 1952 . In addition to Hans Globke and Reinhard Gehlen, Gehlen's employees, Hans von Lossow , Horst Wendland and Werner Repenning, also took part in the secret founding talks that took place in the office of the then Ministerial Councilor Karl Gumbel . One result of the negotiations was that the organization was to be financed entirely from federal funds from April 1, 1953.

On April 1, 1956, the "Organization Gehlen" of the BND emerged from the several thousand employees. Gehlen was appointed President of the Federal Intelligence Service on December 20, 1956, on the basis of a civil service for life. The day before, the Federal Cabinet had approved the change. Gehlen's code name was “Dr. Cutter". Internally, he was also designated with the number 106. With the technical change in secret service work and based on the example of the occupying power of the USA, the gathering of information increasingly shifted from human informers to powerful technical means. When the Bundeswehr was founded, quite a few former Wehrmacht officers switched from the “personnel reserve” to the new regular army. The importance of the old ropes from the days of the "Fremde Heere Ost" dwindled, and civilian, better educated people joined the BND. After all, Gehlen itself became a relic from a bygone era. With his book classified information he disgraced his successor Gerhard Wessel and poisoned the secret service debate for a long time.

Reinhard Gehlen helped Adolf Eichmann's closest colleague , Alois Brunner , who was wanted in Israel and Austria , to flee to Syria and, according to information from Otto Köhler's book Unheimliche Publizisten, was considered a close friend of Gerhard Frey , the founder and chairman of the German People's Union and publisher the national newspaper .

Flanked by an eight-part series in the high-circulation magazine Quick, Gehlen published his memories in 1971 under the title Der Dienst . A 16-part preprint appeared in excerpts in the daily newspaper Die Welt . The book itself reached number one on the Spiegel bestseller list. Critics criticized a technocratic presentation that would contain nothing really new and should primarily make Gehlen himself appear in a brilliant light. The American foreign secret service, the CIA , considered the text to be weak in material, not very exciting and only moderately marketed in the Anglo-American countries. In order to make Gehlen's memoirs appear more dramatic in the English version, David Irving was hired, who edited the text together with his then colleague Elke Fröhlich accordingly.

Reserve officer

On March 30, 1962, Gehlen was promoted to lieutenant general in the reserve . He is the only reservist in the Bundeswehr to have been awarded this rank .

family

Gehlen was a Protestant denomination. From 1931 he was married to the Silesian officer's daughter Herta von Seydlitz- Kurzbach and the father of four children. He was only to find out later about his brother Johannes Gehlen (1901–1986), who later also worked for the Gehlen organization. This grew up in Rome with foster parents. Another brother died in a bomb attack in 1944, and the sister married into a diplomatic family. Gehlen was u. a. Knight of the Catholic Order of Malta .

Awards

- Iron Cross 2nd class

- War Merit Cross II. And I. Class with swords

- German Cross in Silver (March 28, 1945)

- Large Federal Cross of Merit with Star and Shoulder Ribbon (April 30, 1968)

Publications

- The Service: Memories 1942–1971 . v. Hase and Koehler, Mainz, Wiesbaden 1971, ISBN 3-920324-01-3 . (1st place in the Spiegel bestseller list of non-fiction books from October 25 to November 7, 1971)

- Sign of the times: thoughts and Analysis of world politics. Development . v. Hase & Koehler, Mainz 1983, ISBN 3-7758-1041-2 . (First edition 1973)

- Classified information . v. Hase and Koehler, Mainz 1980, ISBN 3-7758-0997-X .

Films and documentaries

- Against Friend and Enemy - A History of the Federal Intelligence Service . Documentary by Michael Müller and Peter F. Müller , WDR, Germany 2002.

- Nazis in the BND - new service and old comrades. Documentary by Christine Rütten , ARTE / HR, Germany 2013.

literature

- Dermot Bradley , Karl Friedrich Hildebrand, Markus Brockmann: The Generals of the Army 1921-1945. The military careers of the generals, as well as the doctors, veterinarians, intendants, judges and ministerial officials in the general rank (= Germany's generals and admirals. Part IV). Volume 4: Fleck - Gyldenfeldt. Biblio, Bissendorf 1996, ISBN 3-7648-2488-3 , pp. 202-203.

- Dermot Bradley, Heinz-Peter Würzenthal, Hansgeorg Model : The Generals and Admirals of the Bundeswehr, 1955–1999. The military careers (= Germany's generals and admirals. Part 6b). Volume 2, 1: Gaedcke - Hoff. Biblio, Osnabrück 2000, ISBN 3-7648-2562-6 , pp. 30-31.

- Heiner Bröckermann : Gehlen, Reinhard (1902–1979). In: David T. Zabecki (Ed.): Germany at war. 400 years of military history. With a foreword by Dennis Showalter , ABC-CLIO, Santa Barbara 2014, ISBN 978-1-59884-980-6 , p. 472.

- James H. Critchfield : Order Pullach. The Gehlen Organization 1948–1956. Mittler, Hamburg a. a. 2005, ISBN 3-8132-0848-6 .

- Jost Dülffer : Secret Service in Crisis. The BND in the 1960s. Ch.links, Berlin 2018, ISBN 978-3-96289-005-6 .

- Dieter Krüger : Reinhard Gehlen (1902–1979). The BND boss as the shadow man of the Adenauer era. In: Dieter Krüger, Armin Wagner (ed.): Conspiracy as a profession. German intelligence chiefs in the Cold War. Ch. Links, Berlin 2003, ISBN 3-86153-287-5 , pp. 207 ff.

- Wolfgang Krieger : “Dr. Schneider “[Gehlen] and the BND. In: Wolfgang Krieger (ed.): Secret Service in World History. Espionage and covert actions from ancient times to the present. CH Beck, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-406-50248-2 , pp. 230-247 (also: Anaconda, Cologne 2007, ISBN 978-3-86647-133-7 ).

- Rolf-Dieter Müller : Reinhard Gehlen. Head of the secret service in the background of the Bonn Republic. 2 volumes, Ch. Links, Berlin 2017, ISBN 978-3-86153-966-7 .

- Timothy Naftali : Reinhard Gehlen and the United States. In: Richard Breitman (Ed.): US Intelligence and the Nazis. Cambridge University Press, New York 2005, ISBN 978-0-521-85268-5 , p. 375 ff.

- Magnus Pahl: Foreign Armies East. Hitler's military enemy reconnaissance. Ch. Links, Berlin 2012, ISBN 978-3-86153-694-9 .

- Mary Ellen Reese: Organization Gehlen. The cold war and the establishment of the German secret service. Rowohlt Verlag, Berlin 1992, ISBN 3-87134-033-2 .

- Jens Wegener: The Gehlen Organization and the USA. German-American secret service relations 1945–1949 (= Studies in Intelligence History. Ed. By Wolfgang Krieger, Shlomo Shpiro and Michael Wala, Volume 2). LIT, Berlin 2008.

- Charles Whiting : Gehlen. Germany's Master Spy. Ballantine, New York 1972, ISBN 0-345-25884-3 .

- Thomas Wolf: The creation of the BND. Development, financing, control (= publications of the Independent Historical Commission for Research into the History of the Federal Intelligence Service 1945–1968. Volume 9). Ch.links , Berlin 2018, ISBN 978-3962890223 ( preview on Google books ).

- Hermann Zolling , Heinz Höhne : Pullach intern. General Gehlen and the history of the Federal Intelligence Service. Hoffmann and Campe, Hamburg 1971, ISBN 3-455-08760-4 .

- Reinhard Gehlen , in Internationales Biographisches Archiv 35/2014 of August 26, 2014, in the Munzinger archive ( beginning of the article freely available)

Web links

- Literature by and about Reinhard Gehlen in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Reinhard Gehlen in the German Digital Library

- Search for "Reinhard Gehlen" in the SPK digital portal of the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation

Individual evidence

- ↑ Walter Habel (Ed.): Who is who? The German who's who. XV. Edition of Degeners who is it? , Berlin 1967, p. 528.

- ↑ As an example from the present time: Magnus Pahl: Fremde Heere Ost. Hitler's military enemy reconnaissance. Ch. Links Verlag , Berlin 2012, ISBN 978-3-86153-694-9 (also dissertation at the Helmut Schmidt University / University of the Federal Armed Forces Hamburg 2011)

- ↑ a b Christopher Simpson: Blowback. America's recruitment of Nazis and its effect on Cold War. Collier Books, New York NY 1989, ISBN 0-02-044995-X , p. 41.

- ↑ Central Intelligence Agency | Gehlen CIA files, released from 2001 (PDF; 1.7 MB). On page 2 above: He operated under G-2 sponsorship from 1946 until 1949

- ^ Gehlen: The service. P. 149 ff. Critchfield, however, only knows a considerably shorter and for the Germans far less positive version of this agreement. Critchfield: Partners at the Creation , p. 39, see also Wegener: Die Organization Gehlen and the USA p. 72

- ↑ Erich Schmidt-Eenboom : An eccentric at the cradle of rearmament - Gehlen's paranoia and the birth pangs of the BND. Research Institute for Peace Policy V.

- ↑ cf. Himmeroder memorandum and Amt Blank

- ^ Hermann Zolling and Heinz Höhne : Pullach intern. The history of the Federal Intelligence Service . In: Der Spiegel 13/1971, March 22, 1971

- ^ "Future Federal Military Security and Intelligence Agencies". Central Intelligence Agency , November 12, 1951, archived from the original on July 13, 2012 ; Retrieved April 18, 2010 .

- ↑ a b Federal Intelligence Service. Central Intelligence Agency , September 12, 1952, archived from the original July 13, 2012 ; Retrieved April 18, 2010 .

- ^ "The Federal Chancellery". Central Intelligence Agency , November 14, 1952, archived from the original on July 13, 2012 ; Retrieved April 18, 2010 .

- ↑ Jerry Richardson, "James H. Critchfield played key roles both in hot and cold war". NDSUmagazine , 2003, archived from the original on September 26, 2011 ; Retrieved October 29, 2011 .

- ↑ Magnus Pahl , Gorch Pieken , Matthias Rogg (eds.): Attention spies! Community services in Germany from 1945 to 1956 - catalog (= Military History Museum of the Federal Armed Forces [Hrsg.]: Series of publications of the Military History Museum . Volume 11 ). 1st edition. Sandstein, Dresden, ISBN 978-3-95498-209-7 , pp. 361 (illustration certificate of appointment).

- ↑ 164th Cabinet meeting on December 19, 1956 - 1. Personal details. In: Federal Archives . December 19, 1956, accessed February 1, 2020 .

- ↑ Concrete Extra - Operation Eva. In: https://konkret-magazin.de/ . August 4, 2015, accessed January 26, 2019 .

-

^ Otto Köhler: Weird Publicists. The suppressed past of the media makers (= Knaur 80071 Politics and Contemporary History ). Completely revised, supplemented and updated by the author for this edition. Droemer Knaur , Munich 1995, ISBN 3-426-80071-3 .

Lutz Hachmeister: White spots in the history of the Federal Intelligence Service . In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung , article in the print edition of May 13, 2008. - ^ Rolf-Dieter Müller : Reinhard Gehlen. Head of the secret service in the background of the Bonn Republic . The biography. Part 2: 1950-1979. Ch. Links, Berlin 2017, ISBN 978-3-86153-966-7 , pp. 1227-1239; the English-language edition appeared in 1972 under the title The Service. The Memoirs of General Reinhard Gehlen at World Publishing, New York, with David Irving as "Translator".

- ↑ Magnus Pahl , Gorch Pieken , Matthias Rogg (eds.): Attention spies! Community services in Germany from 1945 to 1956 - catalog (= Military History Museum of the Federal Armed Forces [Hrsg.]: Series of publications of the Military History Museum . Volume 11 ). 1st edition. Sandstein, Dresden, ISBN 978-3-95498-209-7 , pp. 382 f . (Illustration of the transport order, there March 30, 1962; incorrectly named March 20 in the text).

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Gehlen, Reinhard |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Dr. Tailor (alias); Utility (alias) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German intelligence officer, major general of the Wehrmacht and President of the Federal Intelligence Service |

| DATE OF BIRTH | April 3, 1902 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Erfurt |

| DATE OF DEATH | June 8, 1979 |

| Place of death | Berg near Starnberg |