Abadan crisis

The Abadan Crisis began in March 1951 as a dispute over Iran's mineral resources through the nationalization of Iranian assets by the British-owned Anglo-Iranian Oil Company (AIOC). The crisis lasted until October 1954, when the Iranian parliament gave its approval to the 25-year consortium agreement negotiated with the British and the Americans . The Abadan crisis led to the first exile of Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi , the overthrow of Iranian Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadegh and a complete reorientation of Iranian politics. The end of the term of this contract, which is so important for both the Western oil companies and Iran, coincided with the end of the reign of Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi in 1979.

prehistory

Abadan is a city on the Persian Gulf where oil was discovered in 1908. In 40 years, the Abadan Refinery has grown to become the largest refinery in the world. The refinery, like all other oil facilities in this part of Iran, was operated by the AIOC on the basis of an agreement concluded between the AIOC and Iran in 1933. According to this agreement, which was valid for a period of 60 years, Iran was entitled to approx. 8% of the net proceeds from the sale of crude oil, regardless of further proceeds from the refinery and the sale of finished oil products. The AIOC achieved net proceeds of £ 40 million in 1947, of which £ 7 million was paid to Iran, which corresponds to a rate of only 18%.

During the Second World War and the subsequent Iran crisis , a revision of this agreement was out of the question. Iran was occupied by Allied troops until 1946 and only regained its ability to act internationally in 1947. Following the example of Venezuela , which in 1942 had revised all oil concessions and enforced a 50% share in the net proceeds, the Iranian government wanted to achieve a comparable solution. In February 1949 negotiations began between the AIOC and Minister of Finance Golshaiyan with the aim of revising the 1933 agreement accordingly.

The negotiations did not lead to an agreement, so that in 1950 the newly elected parliament set up a new commission to deal with the question of oil concessions. The chairman of this commission was initially Allahyar Saleh, later Mohammad Mossadegh . In 1950, the Arabian-American Oil Company (ARAMCO) negotiated a new agreement with the Saudis that provided a 50/50 split of net oil revenues. For the Iranian government, parliament and the Shah it was a matter of course that a comparable settlement should be achieved with the AIOC. Should the AIOC not agree to these demands, the oil industry should be nationalized. The negotiations between General Razmara and the AIOC could not be completed because Prime Minister Razmara was shot on March 7, 1951 by a member of the Fedayeen-e Islam , Khalil Tahmasbi. Ayatollah Kashani declared the murderer Razmaras a "savior of the Iranian people" and demanded his immediate release from prison. The next day, Parliament's Oil Commission decided to nationalize the oil industry.

The dispute over the nationalization of the oil industry was conducted as a fundamental political discussion in Iran. For the communist Tudeh party , nationalization was an important step towards a socialist Iran. For Mohammad Mossadegh and his National Front party , it was more about political sovereignty and national honor. The Islamic right pursued a policy against the westernization (gharbsadegi) of Iran, Razmara focused more on technical feasibility. He pointed out that oil, like all mineral resources, already belonged to the Iranian state due to a constitutional article, that ultimately it was only about the nationalization of the refineries and facilities of the oil industry. Razmara said in front of Parliament: “I would like to say very clearly here that Iran currently does not have the industrial possibilities to get the oil out of the earth and sell it on the world market [...] Gentlemen, you can with you The available employees don't even manage a cement factory. [...] I say this very clearly, whoever puts our country's assets and resources at risk is betraying our people. "Mossadegh replied:" I mean, the Iranians only feel hatred for what the Prime Minister has said, and consider a government to be illegitimate to engage in such slavish humiliation. There is no avoiding the nationalization of oil. "

It remains unclear whether Razmara could have successfully concluded negotiations with the AIOC. His violent death initially put an end to the negotiations. On March 15, 1951, a week after Razmara's assassination, parliament passed the law on the nationalization of the oil industry and instructed the parliamentary oil commission to draw up the implementing provisions. The Senate approved the law on March 20, 1951, and the Shah signed it on the same day, putting it into effect. Hossein Ala , the new Prime Minister, should lead the upcoming negotiations with the British. On April 26th, Mossadegh submitted a 9-point plan to the parliamentary oil commission as implementing provisions of the nationalization law, without consulting Ala, whereupon Ala submitted his resignation. On April 29, 1951, the Shah appointed Mossadegh as the new Prime Minister. In the meantime, Parliament had adopted its 9-point plan. On April 30, the 9-point plan was confirmed by the Senate and entered into force on May 1, 1951 with the signature of the Shah.

On the basis of the Nationalization Act, the National Iranian Oil Company (NIOC) began its work in June 1951 . Three members of the provisional board of directors of the NIOC drove to Abadan on June 9 and hoisted the Iranian flag on the headquarters of the refinery on June 10, 1951. They offered the 4,500 British employees of AIOC continued employment with the NIOC. They refused and left the country. At that time, around 61,500 people were employed by the AIOC. The oil production was initially interrupted after the departure of the British employees. The British called the UN Security Council in New York as an arbitration body. In October 1951, Mossadegh went to New York to attend the UN Security Council and the International Court of Justice in The Hague . The meeting in New York did not result in a decision. The dispute over the nationalization of the oil industry developed into the Abadan crisis.

US mediation efforts

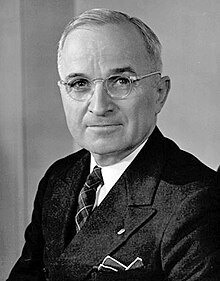

The US had been on friendly terms with Iran since World War II . As part of the Point IV program initiated by President Harry S. Truman , a kind of Marshall Plan for the Middle East , they provided Iran with financial and personnel development aid. Mossadegh went to Washington to meet with President Truman. The Washington government proposed the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD) as the intermediary body. The bank could take over the management of the oil sales for a limited time and offer Iran a loan to finance the resumption of oil production, repayable from the expected oil revenues. This would have the advantage that Iran could again generate income from the oil business until the dispute could be finally settled through further negotiations. Mossadegh agreed to this proposal. The British hesitated.

In the meantime, oil production in Iraq, Kuwait , Saudi Arabia and the USA had increased significantly, so that the failure of Iranian oil had been more than compensated. In addition, the economic situation in Iran deteriorated more and more due to the lack of oil revenues. The British government had meanwhile imposed an export embargo on Iran. In return, Mossadegh ordered the closure of all British consulates in Iran.

On July 22, 1952, the International Court of Justice in The Hague ruled by 9 votes to 5 that the 1933 oil concession was a contract between Iran and a foreign company, that this was therefore not a matter for the British government and that Iran had the right to nationalize the industrial facilities if adequate compensation were offered. Mossadegh was celebrated as a moral victor. The fact was, however, that oil production had dropped from 666,000 barrels a day to 20,000 barrels a day and the oil revenues after deducting wages and salaries were close to zero.

In the second year of the Korean War , the Abadan crisis became an increasing political burden for the US. President Truman did not want to give Mossadegh a reason for rapprochement with the Soviet Union . He convinced the British Prime Minister Winston Churchill to make a new offer to Iran. The offer stipulated that the nationalization of the industrial plants would be recognized, the question of compensation payments would be submitted to the International Court of Justice in The Hague for a decision that the issues of restarting oil production and oil sales would be resolved bilaterally between the AIOC and the Iranian government, and that The export embargo would be relaxed. In addition, the US government wanted to immediately loan $ 10 million to Iran to get the economy going again.

On August 27, 1952, the Churchill-Truman proposal was transmitted to Mossadegh. The latter immediately rejected it. He saw himself as the winner of The Hague, who did not want to tolerate any more British engineers in Abadan. On September 3, 1952, US Secretary of State Acheson made an improved offer at a press conference in Washington, recognizing that the NIOC alone had control over the administration of the Iranian oil industry and proposing that an international one A consortium should be founded, which would buy up the Iranian oil and sell it on the international oil market. If the NIOC had acquired the relevant expertise in the coming years, it could act as an independent seller on the international oil market. Mossadegh also refused this offer. He also stated that the issue of compensation would have to be heard in an Iranian court, as the court in The Hague had already declared that it had no jurisdiction on the matter.

escalation

Churchill still believed in a solution in his favor. Mossadegh had based his policy on what he called "negative balance". The question of foreign concessions had previously been handled by Iranian governments according to the principle of “positive balance”. In the south, for example, the British had obtained an oil concession; to compensate, the Russians in the north received a concession. Mossadegh wanted to use a strictly national policy to free Iran from the dependency of foreign concession income by no longer granting concessions to foreign states or companies. The Iranian oil should be extracted, processed and sold by the NIOC. In the end, Mohammad Reza Shah, Mossadegh and the Iranian parliament agreed on this goal. The only question was how and in what period of time this could be achieved. By nationalizing the oil facilities in Abadan, the Iranian state had complete control over the production and processing of the oil. However, Iran did not have a single tanker to transport the oil to its potential customers, and Iran did not have a navy to keep the sea route through the Persian Gulf open.

The UK expanded the embargo, stating that it would seize all tankers carrying Iranian oil. In July 1952, the Italian tanker Rose Mary with Iranian oil on board was seized by British inspectors in the port of Aden. India , Turkey and Italy , which had signed new contracts with the NIOC, then terminated the supply agreements. The British government also put pressure on the US, Germany , Sweden , Austria and Switzerland governments to ban engineers and technicians who had signed employment contracts with the NIOC from entering Iran. In addition, the Bank of England froze all Iranian sterling accounts for a total of £ 49 million in compensation for nationalizing the Abadan oil facilities. On October 23, 1952, Iran broke off relations with the United Kingdom. The British embargo did not fail to have an effect. The Iranian people began to starve.

Emergency ordinances

Pressure on Mossadegh to find a solution to the Abadan crisis grew. On July 23, 1952, the newly elected parliament passed a kind of emergency law, which gave Mossadegh the opportunity to rule the country by decree for 6 months. He dissolved the Senate, which had fought to the last against the disempowerment of the parliamentary chambers. On October 21, 1952, he passed a law under which anyone could be arrested who called workers and employees to strike, or who went on strike as a government employee or civil servant. Anyone arrested under this law should be found guilty until the police proved innocent. On January 6, 1953, Mossadegh asked parliament to extend his powers for a further 12 months. Numerous members of his party now refused to follow him. The clergy, led by President Kaschani, initially refused to support Mossadegh. In the end, however, Mossadegh succeeded in convincing a majority of MPs that if you withdrew the confidence of his government now, you would only play into the hands of the British. On January 20, 1953, Parliament extended its powers.

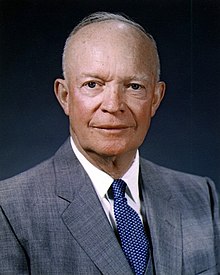

In the USA, the newly elected President Eisenhower took over the office. On February 20, 1953, as part of a proposal coordinated with Churchill, he confirmed the promise of his predecessor Truman to continue mediating with Iran in the negotiations with the British. After the nationalization of the oil industry had been recognized by Great Britain in principle, only the amount of the compensation payments, which were to be financed from the oil sales, had to be clarified. Mossadegh wanted at most to replace the value of the industrial facilities. The Eisenhower-Churchill proposal spoke vaguely of compensation "on the basis of international principles between free nations ...". Mossadegh stood firm and turned down the proposal.

The USA had supported Iran within the framework of the Point IV program initiated by President Truman with more than 44 million dollars in order to prevent a complete collapse of the Iranian economy. In the end, however, the amounts were insufficient to compensate for the lack of oil income. On June 10, 1953, the Soviet Union and Iran signed a new economic agreement. In further negotiations, the Soviet Union offered the return of Iranian gold reserves, which it had confiscated during World War II, border issues should be settled in Iran's favor, and the Soviet-Iranian friendship treaty from 1921 should be renegotiated.

Mossadegh - The People's Tribune

In June 1953, news from Cairo surprised Tehran's politicians . A year earlier, a group of officers - including Gamal Abdel Nasser - deposed King Faruq in favor of his son. On June 18, 1953, the Egyptian Revolutionary Command Council, which until then had been in charge of government, declared Egypt a republic with Muhammad Nagib as its first president and prime minister.

Many members of the Iranian parliament feared or wished for a similar fate for Iran, depending on their political streak. The unity between the Shah, the Mossadegh government and parliament, which had ruled at the beginning of the conflict with the British, was broken due to the worsening economic crisis and the social and political unrest that went with it. The communist Tudeh party meanwhile openly called for the abolition of the monarchy and the establishment of a republic. Mossadegh knew that the parliamentary majority would not follow him here. On July 10, 1953, he announced a referendum. In a referendum he wanted to have the dissolution of parliament voted. On July 21, the Tudeh Party organized a large-scale demonstration with over 100,000 participants to emphasize its call for the abolition of the monarchy, a break with the USA and close cooperation with the Soviet Union.

On July 29, Mossadegh ordered a referendum for August 3 in Tehran and August 10 in the provinces by decree. Mossadegh had ordered that separate ballot boxes should be set up for yes and no votes and that the name of the voter and the date and location of his ID should be noted on each ballot paper. This was a clear breach of the constitution, which provided for secret ballots and elections. The implementation of this arrangement finally went one step further. Separate polling stations had been set up for yes and no votes. Anyone who wanted to enter a "no-bar" was threatened with sticks and knives. 99% of the votes cast were yes-votes.

On August 11, the Shah fled to northern Iran to Ramsar and from there to his summer residence in Kalardasht on the Caspian Sea . On August 12, Mossadegh ordered the arrest of opposition politicians and immediate leave of absence for generals and officers who were critical of him. On August 13, 1953, the Shah signed two decrees (farman) based on the constitution . With the first decree he ordered the removal of Mossadegh. With the second decree he appointed General Zahedi as the new Prime Minister. Colonel Nassiri was to deliver the decrees to General Zahedi and Mossadegh. General Zahedi was an avowed opponent of Mossadegh. Mossadegh had been trying to arrest Zahedi for months.

On August 14th, Mossadegh announced that he wanted to dissolve parliament on the basis of the referendum held earlier. The formal request to the Shah to dissolve the parliament was made on August 15th. On the evening of August 15, Colonel Nassiri Mossadegh delivered the decree with his dismissal, which led to the immediate arrest of Nassiri. Mossadegh defied the Shah's orders. The end of the monarchy seemed to have come. On August 16, 1953, the Shah learned of the arrest of Nassiri, sat down with his wife Soraya in a small sports machine at the airport in Ramsar , flew to Baghdad and asked for “asylum for a few days”. The Iranian ambassador in Baghdad immediately called for the Shah to be extradited to Iran. The Shah flew on to Rome.

Operation Ajax

In Rome, Mohammad Reza Shah explained his view of things to the world press. He had not resigned, he had dismissed Mossadegh as prime minister and he had appointed General Zahedi as the new prime minister. The facts in Tehran said otherwise. Mossadegh continued to act as prime minister and General Zahedi went into hiding after Colonel Nassiri's arrest.

Washington had prepared for all eventualities. The CIA had devised a plan to oust Mossadegh, code-named AJAX. On April 4, 1953, CIA Director Allen Dulles had approved a budget of $ 1 million for the department in Tehran. The plan consisted of three elements: Mohammad Reza Shah was given unreserved support, General Zahedi was to become prime minister, and a propaganda campaign was to prepare for the removal of Mossadegh. In June 1953, Eisenhower approved the CIA's plan. However, these plans formulated in April 1953 were to be overtaken by the events in August.

Legally, Mossadegh had already been ousted and General Zahedi was the new Prime Minister due to the decrees of the Shah. Now this decision of the Shah still had to be enforced. What followed is controversial. In his 1979 book Countercoup, Kermit Roosevelt portrays the CIA and above all himself as “masters of the events” who brought about the forcible removal of Mossadegh and helped General Zahedi to his office as prime minister. Stephen Kinzer revised the remarks by Kermit Roosevelt and published it in 2003 under the title All the Shah's Men . General Zahedi and especially his son Ardeschir Zahedi present the events in a completely different light.

General Zehadi and his son stood ready in Shemiran. Ardeschir had gone into town to reproduce the Shah's decree in a photo shop. Said Hekmat had meanwhile invited the international press to a press conference in his house. Ardeschir distributed the copies of the decree by which his father had been appointed Prime Minister by the Shah with effect from August 15, 1953. Mossadegh's refusal to resign makes him a lawbreaker who is launching a coup against the constitution and the monarchy.

The following day the Shah's decrees were printed in the Tehran daily newspaper Ettelā'āt . Mossadegh said he had put down a military coup but did not comment on the Shah's decrees. Tudeh activists began to tear down the statue of Reza Shah. On Tuesday, August 16, a large Tudeh demonstration called for the establishment of a People's Democratic Republic of Iran. On the evening of the same day, the Shah's supporters marched through the streets with shouts of “Long live the Shah”. On Wednesday the Shah supporters called for the overthrow of Mossadegh. This miraculous twist on the streets of Tehran is attributed to a wrestling troop under Shaban Jafari. He organized a small pro-Shah demonstration. They handed a ten- rial note to anyone who shouted “Long Live the Shah” (javid Shah) . The money came from the CIA coffers. Soon the demonstration had grown to several hundred participants.

On the morning of August 19, 1953, Mossadegh planned a new referendum. But it shouldn't come to that. Pro-Shah demonstrations were underway across Tehran. Troops that were supposed to dissolve the crowd showed solidarity with her. Around 3 p.m., Radio Tehran was in the hands of the Shah supporters and broadcast the national anthem non-stop. The army had completely switched to the side of the Shah supporters. Some tanks, which were actually assigned to the defense of Radio Tehran, drove to the house of Mossadegh, accompanied by a crowd of demonstrators. Several shots were fired in front of the house. But Mossadegh had long since left the house. The crowd broke into the house and started ransacking it. On August 22, 1953, Mossadegh was arrested. On the same day, Mohammad Reza Shah returned to Tehran and met with Prime Minister Zahedi to discuss how to proceed.

It was clear to Mohammad Reza Shah and Prime Minister Zahedi that the first thing to do was to get Iran's economy going again. Eisenhower kept his word and on September 5 made a $ 45 million loan available for immediate use. In addition, $ 23.4 million in economic aid was pledged under the Item IV program. Negotiations with the British on the question of compensation payments for the nationalized refinery in Abadan have resumed. In December 1953, Iran and the United Kingdom resumed diplomatic relations. In the same month the parliament was dissolved by a decree of the Shah. The newly elected parliament was constituted on March 18, 1954.

consequences

The Abadan crisis severely damaged relations between Iran and the United Kingdom. In the eyes of the Iranians, the UK had become a symbol of oppression and exploitation. Conversely, the US had shown itself to be a loyal ally of the Iranian monarchy. After some preliminary talks, negotiations began in April 1954 with the US American Standard Oil , the British AIOC and the Royal Dutch Shell . On August 5, 1954, a framework agreement was signed which recognized that Iran had complete control over its oil stocks. A consortium should be formed to take over the extraction, processing and marketing for the next 25 years. Two companies to be founded and registered in the Netherlands (Iranian Oil Exploration and Producing Co. and Iranian Oil Refining Co.) were to take over the operative business. The consortium called Iranian Oil Participants , which was based in London , was supposed to make the decisions about production volumes and prices. Iran had no representative in this consortium. Compensation for the nationalized Abadan refinery has been set from the requested £ 200 million to £ 25 million payable in installments over 10 years.

Ultimately, no one in Iran was satisfied with the consortium solution. The oil contracts were now processed through Iranian companies. The decisions about the delivery rate and the price per barrel were made by a consortium in which Iran was not represented. Parliament and the Senate approved the treaties in October 1954. Ali Amini, who was in charge of negotiating the treaties for Iran, told parliament: “We are not claiming that this treaty is the ideal solution, nor that we have achieved a solution that our people want. [...] But we have to recognize that we can only enforce our ideas if we have the power, the prosperity and the technical possibilities that allow us to compete with the large and powerful countries. ”Amini had in his Speech in front of parliament formulated the political guidelines for the next 25 years. In 1979, if the agreement were to be renegotiated, Iran should be able to face the Western powers as an equal partner in order to finally be able to determine for itself what quantity and at what price Iranian oil can be extracted, processed and sold.

See also

literature

- Alan W. Ford: The Anglo-Iranian Oil Dispute 1951–1952. A Study of the Role of Law in the Relations of States. University of California Press, Berkeley CA et al. 1954.

- Gérard de Villiers : The Shah. The unstoppable rise of Mohammed Reza Pahlewi. Econ-Verlag, Vienna et al. 1975, ISBN 3-430-19364-8 .

- Stephen Kinzer: All the Shah's Men. An American Coup and the Roots of Middle East Terror. John Wiley and Sons, Hoboken NJ 2003, ISBN 0-471-26517-9 .

- Gerhard Altmann: Farewell to the Empire. The internal decolonization of Great Britain 1945–1985 (= Modern Era 8). Wallstein-Verlag, Göttingen 2005, ISBN 3-89244-870-1 (also: Freiburg, Univ., Diss., 2003-2004).

- Manucher Farmanfarmaian, Roxanne Farmanfarmaian: Blood and Oil. A Prince's Memoir of Iran, from the Shah to the Ayatollah. Random House, New York NY 2005, ISBN 0-8129-7508-1 .

- Gholam Reza Afkhami: The Life and Times of the Shah. University of California Press, Berkeley CA et al. 2009, ISBN 978-0-520-25328-5 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Afkhami: The Life and Times of the Shah. 2009, p. 118.

- ↑ Kinzer: All the Shah's Men. 2003, p. 67.

- ↑ Afkhami: The Life and Times of the Shah. 2009, p. 115.

- ↑ Afkhami: The Life and Times of the Shah. 2009, p. 116 f.

- ↑ Rahim Zehtab Fard: Afsane-ye Mosaddeq. ( The Mosaddeg Myth ). Nashr-e Elmi, Tehran 1376 (1997), ISBN 964-5989-66-3 , p. 230.

- ^ Brief History. In: www.nioc.ir. NIOC - National Iranian Oil Company, 2003, archived from the original on September 26, 2009 ; accessed on August 6, 2013 .

- ↑ Afkhami: The Life and Times of the Shah. 2009, p. 130.

- ^ A b Farmanfarmaian: Blood and Oil. 2005, p. 275.

- ↑ Afkhami: The Life and Times of the Shah. 2009, p. 144.

- ↑ Afkhami: The Life and Times of the Shah. 2009, p. 145.

- ^ Mohammad Reza Pahlavi: Answer to History. Stein and Day, New York NY 1980, ISBN 0-8128-2755-4 , p. 85.

- ^ Farmanfarmaian: Blood and Oil. 2005, p. 279.

- ↑ Ervand Abrahamian: Iran between two revolutions. Princeton University Press, Princeton NJ 1982, ISBN 0-691-05342-1 , p. 273.

- ↑ Afkhami: The Life and Times of the Shah. 2009, p. 148.

- ↑ Afkhami: The Life and Times of the Shah. 2009, p. 151.

- ↑ 100,000 Red Rally in Iranian Capital. In: New York Times , July 15, 1953.

- ^ Mossadegh Voids Secret Balloting. Decrees "Yes" and "No" Booths for Iranian Plebiscite on Dissolution of Majlis. In: New York Times , July 28, 1953.

- ↑ a b Afkhami: The Life and Times of the Shah. 2009, p. 156.

- ^ De Villiers: The Shah. 1975. p. 277.

- ↑ Kinzer: All the Shah's Men. 2003, p. 161.

- ↑ Afkhami: The Life and Times of the Shah. 2009, p. 171.

- ^ De Villiers: The Shah. 1975, p. 292.

- ↑ Afkhami: The Life and Times of the Shah. 2009, p. 178.

- ↑ Afkhami: The Life and Times of the Shah. 2009, p. 198.

- ↑ Afkhami: The Life and Times of the Shah. 2009, p. 199.