Old maps from Japan

This article covers ancient maps from Japan from early known examples to the 19th century.

Card types

Japan maps

When Japan began to build a new government structure based on the Chinese model in the middle of the seventh century, maps were also produced to ensure control of the country. Tradition ascribes these first cards to the monk Gyōki (670-749), who advised Emperor Shōmu . Maps from his hand have not survived, and those that bear his name do not show Heijō-kyō ( Nara ) as the center of Japan during his lifetime, but the later Heian-kyō (Kyōto) with the " Five Roads " extending from there as Focus. These Gyōki maps show the Japanese provinces, the arrangement and layout of which remained unchanged over a thousand years through all political changes until the reorganization after 1868.

The earliest existing map of Japan of the Gyōki type is a copy of a map from the year 805. It is kept in the Shimogamo Shrine in Kyoto. The Ninna-ji has a card from 1305. A well-known example of a Gyōki card can be found in the "Shūgaisho" The Gyōki card remained popular until the 19th century and is used as a decoration on plates.

More detailed maps of Japan were produced in the Edo period. The Nakabayashi map from 1666 bears the designation "Fusōkoku no zu" ( 扶桑 國 之 F ), whereby Fuzōkoku is a name for Japan adopted from China. The map shows the number of administrative districts (郡. Gun) for each province, often also place names and castle symbols. Below the map, the provinces are listed in the traditional order, starting with the "Five Provinces" (around Kyoto). For each province the number of inhabitants is given, Musashi Province , e.g. B. with 840,000 inhabitants.

The increasing threat to isolated Japan from ships from western countries led to the first measurement of Japan from 1800 using measuring instruments based on the European model. It was Inō Tadataka who tirelessly walked the entire coast to measure them on foot. He did not live to see the print editions completed, and Siebold was able to purchase a map of Japan, the first to show the country topographically correctly. Since these cards were used for national defense and distribution was strictly forbidden, the Siebold incident occurred .

Travel cards

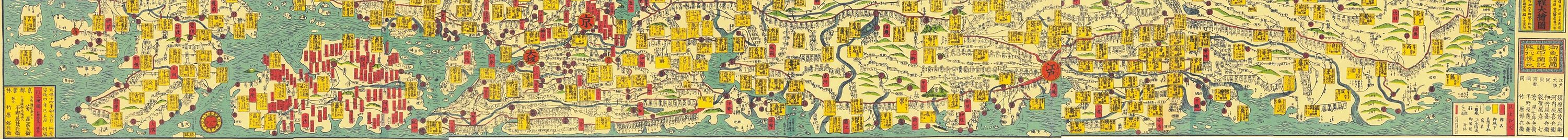

In the Edo period, travel between the center and the periphery increased. Businessmen and pilgrims were on the move, as the streets were filled with daimyo delegations who moved to Edo and then back home as part of the Sankin kōtai arrangement. For journeys across the whole country, the " en route maps" ( 道 中 絵 図 , dōchū-ezu) came into use, which show Japan in a very elongated form in order to accommodate all places on the interurban roads. Folded in a fan-fold style, these cards were easy to use.

The map shown "Greater Japan maps with distance information " "( 大 日本 行程 大 絵 図 , Dainihon kōtei dai-ezu) from 1857 has a format of 27 × 204 cm. It is produced in multi-color printing, shows streets, sea routes, towns, Castles (in yellow cartouches with information about the lord of the castle, his income, the distance from Edo), temples, shrines (both in red cartouches) and other sights and gives further information.

For the princes, who had to travel to Edo more often because of the compulsory attendance, special maps were made on which the view from the litter to the right and left was graphically drawn.

Province maps

In addition to the Japan maps, maps of the individual provinces were also produced. They contain the cities as labeled circles and the villages as labeled ellipses. As can be seen from the section Edo, the Edo Castle is precisely defined, but the surrounding districts belong to different counties.

City maps

The large cities of Edo, Kyoto and Osaka also had city maps by the Edo period at the latest. While these show the entire road network for Kyōto and Osaka, this was not possible for maps for the extensive Edo, at least they were used for general orientation. These Edo cards are very decorative and often contain information on distances to other places in Japan. Basically, the west is up. Properties belonging to the sword nobility are marked by the respective coat of arms in red.

These decorative cards were not very accurate in detail. The fact that Edo also had precise plans at that time is proven by a 3 × 4 m Edo card owned by the Mitsui-Bunko : It shows a precisely measured Edo with all the bearing directions from raised points.

District maps

In order to find one's way in the spacious Edo, city maps could only provide a rough orientation. At the beginning of the 19th century, the publishers began to issue district maps "Kiri-ezu" (切 絵 図), in which every property was recorded. One set for the whole city consisted of up to 30 sheets with a little overlap. Each district was pragmatically distorted and fitted into a map rectangle that was easy to fold.

The cards were produced in 6-color printing. They indicated the daimyo's properties with coats of arms and names, those of the samurai only with names. In addition, the maps contained the names of the temples marked in red, information about steep slopes , sentry boxes and barriers. From time to time new editions appeared due to changes in ownership and other corrections.

Hosokawa residence

Temple Kan'ei-ji

Port facility on the Sumida River

World maps

The first cards to go beyond Japan were the Tenjiku cards, Tenjiku ( 天竺 図 ) being an old name for India. These maps show the world with India in the center, with Sri Lanka in the southeast. They have been modified to include Japan in the upper right margin. The center of this world was thought to be in the Himalayas . The rivers Indus and Ganges emanate from it. In this worldview it got colder and colder to the north, hotter and hotter to the south, the mountains got higher and higher to the west, the endless sea stretched to the east.

With the Jesuits around 1600, modern world maps came to Japan. Matteo Ricci had already had a world map " Kunyu Wanguo Quantu " printed in China in 1602 as a six-part woodcut of astonishing dimensions: it was one and a half meters high and three and a half meters wide. The non-Chinese countries and places were reproduced loudly using Chinese characters.

The world map with its Chinese characters was also used by the Japanese. The spelling was used there. For example, “Berlin” is shown on the map with “柏林”, which is read as “Bo-lin” in Chinese. However, the Japanese would read this symbol or the related pair “als” as “Haku-rin” without knowing the context.

Map collections in Japan

Map collections can be found in archives, libraries, and museums across Japan. Two collections are particularly important:

- The "Namba Collection" in the Kobe City Museum . It goes back to Namba Matsutarō (南波松 太郎; 1894–1995), who was professor of shipbuilding at the University of Tokyo , and also long-time president of the Japan Society for Marine History. From the 4000-sheet collection, the catalog lists sheets from various parts of Japan:

- 196 world maps from the early Edo period to the beginning of the Meiji period,

- 298 maps of Japan; 27 partial maps of Japan,

- 256 cards of Edo, 201 cards of Kyoto, 104 cards of Osaka. The best known is the pair of adjustable screens with the title "Kon'yo bankoku zenzu" (坤 輿 万 国 全 図).

- The Akioka collection in the National Museum of History and Folklore Sakura (Chiba) goes back to Akioka Takejirō (秋岡 竹 次郎; 1895-1975), who had worked as a professor of geography, also at the University of Tokyo. The collection includes over a thousand sheets.

Reception in Europe

Since Marco Polo , the existence of Japan, then known as " Zipangu ", was known in Europe , as was its approximate location. After the Portuguese arrived in Japan, more detailed maps of Japan came to Europe at the end of the 16th century. Typical for these maps, which come from Japanese sources, is the emphasis on the east-west direction with the less important and therefore strongly shortened northern Japan. These maps were then copied and reproduced in Europe and shaped the image of Japan until the 19th century. Siebold was the first to bring better maps: they were the first truly measured maps of Japan and thus gave a much more accurate picture of the country.

Before that, Engelbert Kaempfer had not only brought maps of Japan from his stay in Japan in 1691/92, but also of parts of the country and cities to Europe. After his death they came to the British Museum and served as a template for the illustrations in the encyclopedic work "History of Japan" (1727), which was initially published in English. The draftsman made a mistake when producing the printing plate for the plan of the city of Edo : The easternmost part of the city on the other side of the Sumida River, which is usually attached to the map sheet on the right as a fold-out appendix, was in this original, however, in a vacant place, in the sea, so to speak , inserted. When converted into the engraving, this part was understood as a land mass extending further south and drawn connected. This error was then propagated in other European works that referred to the Kaempfer edition.

Remarks

- ↑ A phantom island on which women are supposed to live is marked in red.

- ↑ The three-volume Shūgaishō ( 拾 芥 抄 ), with the poetic name "picked mustard seeds", was a kind of encyclopedia of knowledge from the middle of the Kamakura period .

Individual evidence

- ^ Lutz Walter (Ed.): Japan. Seen with the eyes of the west. Prestel Verlag, 1994, ISBN 3-7913-1291-X .

- ↑ See Edo in Bellin and Schley for Prevost (eds.): Histoire Generale des Voyages. 1752.

- ↑ See Edo In: Prevost et al. (Ed.): Collection of all travel descriptions. Volume 11, Leipzig 1753.

literature

- City Museum Kobe (Ed.): Kochizu no sekai. Namba Matsutaroshi-shu. 1983.

- City Museum Kobe (Ed.): Kochizu ni miru sekai to Nihon. 1983.

- Takejiro Akioka: Nihon chizu shi. 1955. (Reprint: Myujium tosho, 1997, ISBN 4-944113-23-4 )

- M. Nanba, M. Nobuo, K. Unno (Eds.): Nihon no kochizu. Sogen-sha, 1969-

- Takeo Oda: Chizu no rekishi. Nihon-nen, Kodansha Gendai-Shinsho No 368, ISBN 4-06-115769-8 .

- Kazutaka Unno : Chizu no shiwa. Yushodo shuppan, 1985, ISBN 4-8419-0009-8 .

- Kazutaka Unno: Chizu no bunka-shi sekai to Nihon. Yasaka Shobo, 1996, ISBN 4-89694-673-1 .

- Kazuhiko Yamori: Kochizu heno tabi. Asahi Shimbunsha, 1992, ISBN 4-02-256456-3 .