Bow brooch from Charnay

The Charnay bow fibula (KJ 6; O 10) is a Merovingian Frankish fibula from the second half of the 6th century from Charnay-lès-Chalon , Saône-et-Loire in France . The fibula bears two runic inscriptions on the back, one of which is an almost complete older futhark .

Finding and describing

The fibula presumably comes from a woman's grave in a large row grave field comprising several hundred graves near Charnay on a bank of the Saône, which the French archaeologist Henri Baudot excavated from 1832. Numerous finds of various grave goods were made, but they were not handed down as closed inventories. In research, the finds were rated as Franconian with a Burgundian touch, according to Helmut Roth, probably due to the additions in the form of the large and heavy silver-plated iron belt fittings. However, it is also possible that the local Gallo-Roman (Christianized) population adapted or returned to the funerary customs of the new masters, initially the Burgundians (since 443 AD) and the subsequent Franks (since 534). This group is probably recognizable through the Christian treasure trove of belt fittings.

In addition to the fibula with runes, a fragmentary piece of the same pattern was found. The primer has been in the depot of the Musée d'Archéologie Nationale in Saint-Germain-en-Laye since 1894 (inventory no. 34722). The state of preservation is poor today, due to the fact that in recent decades the piece in the museum has broken for unexplained reasons and was glued at the break points.

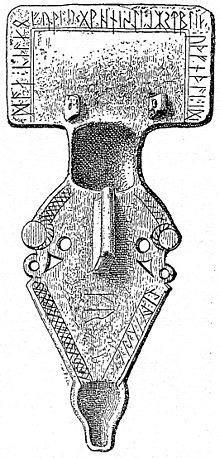

The 9.4 cm long fibula is made of fire-gilded cast silver, has a rectangular head plate, a short and strongly curved bracket and a polished diamond-shaped base plate. Head and foot plate fields as well as the bow fields show a narrow step band (only head plate and bow) and individual spiral hooks that were placed in small squares. The back of the footplate shows a circumferential ornament band in the form of rhombuses that is framed by two lines. The front shows two stylized animal heads hanging at the side, each with three openings at the mouth cracks and an end designed with an animal head.

Typologically, the primer corresponds to North Germanic models and their imitations in continental and insular tribes / peoples such as the Anglo-Saxons, Thuringians, Franks and Alemanni. The step band of the headstock field and the bow appears mainly in the Lombard finds contexts in Pannonia and Italy, the spiral hooks in the East Germanic bow brooch from Aquincum . Max Martin assumes that female migrants from northern Francia introduced this form of fibula to the region of Burgundy. Despite the East Germanic elements of form, he considers the primers to be local Franconian products. The production is dated to the second half of the 6th century.

Inscriptions

The fibula bears two clockwise inscriptions on the back of the headstock: an older Futhark on the long side and a coherent short text on the narrow sides. On the back of the footplate there are rune sequences below the needle holder and on the edge at the level of the needle holder, which do not allow any conclusive interpretation.

The runes of the so-called Charnay-Futhark include the runes ᚠ = f to ᛗ = m, the last runes for the sound values l, ng, d, o ( ᛚ ᛜ ᛞ ᛟ ) are missing . The r-rune ᚱ appears in a more openly scored form. The h-Rune ᚺ shows the doppelzweigigen variant ᚻ südgermanischen continental character; Robert Nedoma is different, who notes that the upper branch is only half executed and therefore does not necessarily have the South Germanic peculiarity. The j-rune ᛃ shows a different shapeᛋas it appears in the inscriptions on the lance shaft of Kragehul (Kragehul I) and on the disc brooch from Oettingen . Two other variants show the p-Rune ᛈ the w-shape of a vertically mirrored e-Rune ᛖ similar and the z-Rune ᛉ provided with a doppelzweigigen form ᛯ was scratched. These two variants are unique in the corpus of the runic inscriptions or the traditional rune rows.

- I. a: ᚠᚢᚦᚨᚱᚲᚷᚹᚺᚾᛁᛋᛇᛈᛯᛊᛏᛒᛖᛗ

- fuþarkgwhnijïpzstbẹṃ

The rune no. 4 in I. c shows a special shape or a variant of the l-rune ᛚ which is similar in shape to the Anglo-Saxon Futhorc k-rune ᚳ .

- I. b: ⋮ ᚢᚦᚠᚾᚦᚨᛁ ⋮ ᛁᛞ

- ⋮ uþfnþai ⋮ id

- I. c: ᛞᚨᚾ ⋮ ᚳᛁᚨᚾᛟ

- dan ⋮ ḷiano

A possible transfer of the inscription is (according to Krause): "May the Idda Liano (woman's name) find out".

The inscriptions in the area of the needle holder show a variation with the k rune in II . In III. If the reading is unclear whether the first rune is either a ᛇ or ᛚ , the reading of the i and a runes is clear.

- II .: ᚴᚱ

- kr

- III .: ᛇᛁᚨ

- ï / ḷ ia

Interpretations

The interpretations of the inscription I. b + c in relation to I. a are varied and overall is not yet considered satisfactory. According to the inscription, a donation is generally assumed as the purpose. Furthermore, East Germanic-Burgundian is best assumed for the language. Deviating, Elmer H. Antonsen explained the language with problematic interference ( Klaus Düwel ) in the rune sequence in the sequence I. c uþfnþai das / n / for the vowel / a / to Germanic * / faþ-aj-i / (Gothic -faþs , fadis = "lord, leader"; idg. * / pot-oy-i / among others to Greek πόσις pósis "husband, husband") the language for West Germanic. He explains the inscription as “for (my) husband Iddo. Liano "

Heinz Klingenberg , whom Opitz follows, creates a Christian reference to the Burgundian Daniel buckles , which receive the biblical motif of "Daniel in the lions' den" in pictures and inscriptions. Klingenberg elaborates his result by making syntactic interventions in order to convert Iddan and Liano, which are generally recognized as two personal names , to danianoliano by separating the id . According to Klingenberg's interpretation, the reader of the inscription should find out that behind the formal script there is a "Daniel and a lion" (too Gothic * laíon ). Klingenberg's interpretations and complicated procedures are rejected or treated skeptically in research.

Wolfgang Krause interprets I. b + c ("u (n) þf (i) nþai Iddan Liano" = may Liano find out the Idda ) as meaning that person A (Liano) is the name of person B (Idda) from the Futhark should decipher and thus the purpose and the meaning of the inscription should serve the playful teaching purpose and acquisition of "rune competence". Düwel / Heizmann criticize Krause's interpretation as a construct that is difficult to imagine, since it lacks the comprehensible "seat in life" as an important methodological approach in runology.

literature

- Elmer H. Antonsen : Runes and Germanic Linguistics. (= Trends in Linguistics. Studies and Monographs. Volume 140). Mouton de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2002.

- Franz Dietrich : The Burgundian runic inscription from Charnay. In: Journal for German antiquity . Volume 13, 1867, pp. 105-122.

- Klaus Düwel : Runic lore. 4th edition. Metzler, Stuttgart 2008, p. 57.

- Klaus Düwel, Helmut Roth : Charnay. In: Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde (RGA). 2nd Edition. Volume 4, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1981, ISBN 3-11-006513-4 , pp. 372-375. ( Fee Germanic archeology online by de Gruyter)

- Klaus Düwel, Wilhelm Heizmann : The older Fuþark - tradition and possible effects of the rune series. In: Alfred Bammesberger , Gabriele Waxenberger (Hrsg.): The fuþark and its individual language developments. (= Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde - supplementary volumes . Volume 51). Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2006, ISBN 3-11-019008-7 , pp. 3-60.

- Wolfgang Krause , Herbert Jankuhn : The runic inscriptions in the older Futhark. (= Treatises of the Academy of Sciences in Göttingen, Philosophical-Historical Class. Volume 3, No. 65.1 (text), No. 65.2 (tables)). Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1966.

- Tineke Looijenga: Texts & contexts of the oldest Runic inscriptions. (= The Northern World. Volume 4). Brill, Leiden / Boston 2003, ISBN 90-04-12396-2 .

- John McKinnell , Rudolf Simek , Klaus Düwel: Runes, Magic and Religion. (= Studia Medievalia Septentrionalia . Volume 10). Fassbaender, Vienna 2004, ISBN 3-900538-81-6 , pp. 87-88.

- Robert Nedoma : Script and language in the East Germanic runic inscriptions. In: NOWELE . Volume 58/59, 2010, pp. 1-70.

- Robert Nedoma: Personal names in older runic inscriptions on fibulae. In: NOWELE. Volume 62/63, 2011, pp. 31-89.

- Stephan Opitz : South Germanic runic inscriptions in the older Futhark from the Merovingian period. (= University productions German studies, linguistics, literary studies. 3). 2nd edition, Kirchzarten 1980.

Web links

- Runic project of the University of Kiel:

Remarks

- ^ Henri Baudot: Mémoire sur les sépultures des barbaren de l'époque mérovingienne découvertes en Bourgogne et particulièrement à Charnay. In: Mémoires Comm. des antiquités du dép. de la Côte-d'Or. Volume 5, 1857-1860.

- ^ Max Martin: Burgundy. III Archaeological (443-700). In: Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde (RGA). 2nd Edition. Volume 4, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1981, ISBN 3-11-006513-4 , pp. 248-271 ( online ). The same: Continental Germanic runic inscriptions and 'Alamannic runic province' from an archaeological point of view. In: Hans-Peter Naumann (Ed.): Allemanien und der Norden. (= Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde - supplementary volumes . Volume 43). Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2004, ISBN 3-11-017891-5 , p. 179 ( online ).

- ^ Also in the inscriptions from: Nebenstedt (I) B, Fünen (I) -C, Grumpan-C, Hitsum, Dahmsdorf, Britsum, Balingen, Osthofen, Aquincum, and Eskatorp-F, Väsby-F.

- ↑ runes project Kiel: Profile: lance / spear Kragehul

- ^ Nedoma: Script and language in the East Germanic runic inscriptions. Pp. 39-40.

- ^ Elmer H. Antonsen: A Concise Grammar of the Older Runic Inscriptions. Max Niemeyer Verlag, Tübingen 1975, ISBN 3-484-60052-7 , pp. 77-78.

- ↑ Heinz Klingenberg: Runic writing - writing thinking - runic inscriptions. (= Germanic library. Third row. Investigations and individual presentations ). Universitätsverlag Winter, Heidelberg 1973, p. 267ff.