Siege of Breisach

| date | May 1638 to December 17, 1638 |

|---|---|

| place |

Breisach |

| output | Surrender of the Breisach Fortress |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

|

France , Sweden , Protestants |

Imperial troops , Bavaria, Catholics |

| Commander | |

| Troop strength | |

| 12,000 | 4000 |

| losses | |

|

3500 |

|

Wallerfangen - Dömitz - Haselünne - Wittstock - Rheinfelden siege - Rheinfelden battle - Breisach Siege - Witten Weiher - Vlotho - Ochsenfeld - Chemnitz - Bautzen siege - Freiberg sieges - Riebel Dorfer Mountain - Dorsten - Preßnitz - La Marfée - Wolfenbüttel siege - Kempen Heath - Swidnica - Breitenfeld - Klingenthal - Tuttlingen - Freiburg - Jüterbog - Jankau - Herbsthausen - Alerheim - Korneuburg - Totenhöhe - Hohentübingen - Triebl - Zusmarshausen - Wevelinghoven - Dachau - Prague siege

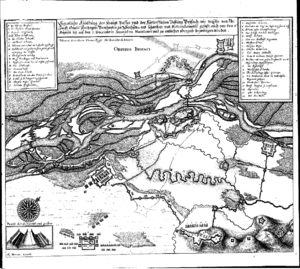

The 8-month siege of Breisach from May to December 1638 went down in military history because Breisach had the reputation of a key fortress on the Rhine and was of great importance to the Habsburgs at the beginning of the war. The imperial fortress was considered the key to the empire , which was expressed in the short phrase Breisach lost, all lost .

Swedish troops under Otto Ludwig von Salm had already besieged Breisach in the summer of 1633 , but the siege failed on October 11, 1633 when a relief army with 26,000 men under Duke Feria was able to drive out the siege troops. The re-siege of the fortress occupied by imperial troops by a Franco-Swedish army of Bernhard von Sachsen-Weimar began in May 1638 and ended successfully on December 17, 1638 with the handover of the fortress . Before the handover, numerous attempts at relief by Imperial Bavarian troops had failed.

Location and importance of the Breisach fortress

The Breisach Fortress lay on a hill and was surrounded by a triple wall and deep moats. A stone bridge led to the left bank of the Rhine, which was secured with a strong bridgehead. The governor of the fortress was Hans von Reinach . The fortress was the most important and strongest fortress in the south-west of the empire. It controlled the cross connection across the Rhine between Alsace-Lorraine and Baden and the handling of goods from Switzerland, especially from Basel, down the Rhine.

The Rhine as a south-north waterway and transport route to the Spanish Netherlands was of great importance to the Habsburgs at the beginning of the war. However, the importance took during the war quickly, because these Water Street became more difficult to negotiate. The conquest of the Breisach Fortress did not turn into a turning point in the war, but was - viewed retrospectively - only the forerunner of the end of the career of its conqueror Bernhard von Sachsen-Weimar.

chronology

In the battle of Rheinfelden (double battle on February 28 and March 3, 1638) the Protestant general Bernhard von Sachsen-Weimar, who was in the service of France, defeated his Catholic, imperial-Bavarian opponents Federigo Savelli and Johann von Werth . After the victory, Bernhard was able to start conquering the cities on the Rhine in order to conquer a new duchy on the Rhine with French support. The important city of Freiburg surrendered to him on April 12, 1638; a first attempt to retake the city failed on April 24th.

May

Bernhard now turned to the Breisach fortress . The task of the siege fell initially to the governor of Freiburg, Colonel Kanoffski , while Bernhard wanted to repel the expected relief troops. The siege troops comprised 6,000 infantry, 5,800 horsemen, 400 workers and 25 artillery pieces. The garrison of Breisach was 3,000 strong, but had only a small supply of food, as a long siege was not considered possible.

The siege ring could not be fully closed at first and the cavalry of the imperial troops under Johann von Götzen , who arrived on May 19 before Breisach, managed to bring 500 sacks of flour and reinforcements into the fortress. Swedish troops under Colonel Taupadel tried to close the gap in the siege, but at the end of May the defenders of Breisach were able to intercept a transport of bread from Basel and bring it to the fortress.

June

A bridge was built near Neuchâtel and a ski jump on a Rhine island. In order to prevent attempts to break through, the Rhine was blocked with chains. But the siege did not advance; an attempt to destroy the Rhine bridge with a fire failed. Nevertheless, on June 26th, a train from Kenzingen was able to bring new supplies. This was also urgently needed, because on July 1st, hungry soldiers broke into a supply warehouse and accidentally ignited the powder stored there. 40 houses as well as some flour and powder were destroyed. Attempts by the cavalry to penetrate Alsace and steal corn there were also prevented.

July

On July 9th, Colonel Taupaldel met seven imperial cavalry regiments near Benfeld. Although they were still supported by Croatians and musketeers, he was able to beat them. Thirteen standards, the hostile train and over 1000 horses were captured.

An advance by the besiegers to Kenzingen and Offenburg on July 14th was also rejected, and Duke Bernhard returned to Freiburg on July 28th. On July 23, an island was also fortified with a hill upstream from Breisach.

August

On August 7, a relief army of 18,500 marched under Federigo Savelli and Johann von Götzen von Offenburg towards Breisach. Bernhard took 13,000 men and went to meet the entourage. A battle broke out near Wittenweiher and the imperial army was crushed. Only 3,000 soldiers gathered again in Offenburg. On August 12th, Kenzingen and Lichteneck Castle surrendered near Kenzingen. Mahlberg surrendered on August 21 .

Bernhard fell ill and went to Colmar . He handed over the command of the siege to General Johann Ludwig von Erlach and the observation army to Colonel Reinhold von Rosen . Several attempts by General Horst to bring food into the fortress with seven cavalry regiments failed. The besiegers built two ship bridges above the fortress and blocked the Rhine with chains. The urban and rural populations were forced to expand the camps. 2000 citizens and 200 craftsmen were busy expanding the camp in August, September and partly in October.

September

The month was marked by the little war . General Horst's Croats tried to get supplies to the fortress. On September 5, Colonels Rosen and Kanoffski marched towards a larger group via St Peter. Kanoffski intercepted a small group of 100 men on a ravine. 20 were killed; the others escaped leaving the goods behind. The following day Rosen managed to disperse a large group. The imperial counted 200 dead and 60 wounded. Nevertheless, on September 10th, 300 men were able to cross the Rhine near Drusenheim and reach the fortress.

On September 22nd, Weimar's troops near Offenburg captured a herd of 300 cattle. At the same time, however, 400 Croatians attacked Lagen in Neuchâtel and captured 200 horses and cattle. Colonel Zyllnhardt and Commissioner General Schaffalitzky (1591–1641) had just returned from Basel and rode straight into the arms of the Croatian.

October

The Duke's troops had conquered some small entrenchments under Colonels Schönebeck and Kluge, and on October 7th also a larger one on an island on the Rhine.

In October the imperial troops tried to attack the siege ring from two sides. The Duke Charles of Lorraine was supposed to bring troops and supplies to the fortress with a train from Alsace. At the same time, the von Götzens army was supposed to attack the fortified camp of the besiegers and so blow up the ring. On his sick bed in Colmar he learned of the advancing troops. He gathered his units on the left bank of the Rhine and first marched towards the duke, whom he defeated on October 15, 1638 in a meeting on the Ochsenfelde near Thann .

The Brückenschanze was conquered on October 19, and Rheinach had to give up the Mühlenschanze.

Bernhard marched immediately to Breisach and on the same day met French reinforcements by 4,000 men under Marshal Guébriant . In the meantime Johann von Götzen had raised an army of 10,000 men and united with General Lamboy on October 19th . On October 22nd, the besiegers were attacked. The troops managed to advance into the camp in front of Breisach, but with heavy losses (1,500 deaths) they were pushed back behind Freiburg by October 26th. In Waldkirch , Lamboy and Götzen parted in a dispute. So he had to withdraw to Schaffhausen .

Bernhard sent the commandant of Breisach Rheinach a request to surrender, but the latter refused, although bread made from oak bark had to be baked. On October 28, Rheinach had to give up part of the external works. On October 30th the Eisenberg fell and with it the last outer works. It was conquered by the French under Turenne and Roqueverfere.

Meanwhile, a new plan has been developed in Schaffhausen. The Duke of Lorraine was to advance towards Colmar, and General Horst with 6,000 horsemen was to join him via Drusenheim . Götzen himself wanted to cross the Rhine with the main army near Hüningen or Neuchâtel and thus relieve the fortress. But the couriers were intercepted, and Bernhard received French reinforcements from 9,000 men under Longueville . General Horst was beaten, Bernhard pulled against Götzen and pushed him back to Waldshut. The Duke of Lorraine did not even advance to Colmar.

November

On November 5th, General Longueville met Duke Savelli's troops and defeated them. They retreat to the Moselle. On November 25th Rheinach was asked to surrender again, which the latter refused with reference to the coming relief and his orders.

December

On December 2nd the imperial envoy Philipp von Mansfeld reached the camp near Waldshut . Götzen was arrested on the pretext of being secretly in league with Bernhard von Weimar and transferred to Munich. It wasn't until two years later that the allegations were withdrawn. On December 3, a powder tower of the fortress exploded and tore a breach in the wall. However, on the advice of General Erlach, Bernhard von Weimar continued to wait.

Rheinach now negotiated with General Erlach to hand over the fortress, since Bernhard von Weimar was sick in Neuchâtel. On December 17th, the fortress and Landskron Castle were handed over. When Duke Bernhard learned that some of his captured soldiers had starved to death, he initially refused to sign the contract. The assembled officers were still able to change his mind.

On December 19, 1638, the survivors moved out with flying colors: Rheinach and the Austrian Chancellor Volmer, as well as Colonel Aescher (Hans Werner Aescher von Büningen) with the approximately 400 remaining soldiers, who were to take the route to Strasbourg completely emaciated.

The besiegers found numerous military equipment in the fortress as well as a war chest of more than 1,000,000 thalers, which more than outweighed the costs of the siege. It was estimated that about 8,000 died on the besiegers side and about 16,000 soldiers on the other side.

Conditions in the fortress

There are few reports of conditions in the city during the siege, but they are always described as horrific. Even if their description was misused for propaganda purposes even then, some of the figures speak for themselves.

Of the approximately 4,000 inhabitants, only 150 survived the siege. The cemeteries had to be guarded so that the dead were not dug up and eaten. The guards are often said to have been corruptible. The prices for bread and wine are said to have reached adventurous prices: 3 pounds of bread and 1 measure of wine could be exchanged for a diamond ring. The price of a rat was one guilder, a quarter of a dog cost 7 guilders and animal skins 7 guilders. The animal skins were boiled and eaten. Farmers caught smuggling food into the fortress were hung up in sight. In such conditions, it is hardly surprising that soldiers fell from the walls of weakness when they fired their muskets. The prisoners were hit particularly hard. Thirty of them are said to have starved to death and eight were eaten, which almost led to the crew being refused permission to leave. The surrounding area was also affected, as the besiegers roamed here in search of food and building materials.

literature

- Hans Eggert Willibald von der Lühe, Militair-Conversations-Lexikon , Volume 1, p. 694ff, digitized

- Friedrich Rudolf von Rothenburg, battles, sieges and skirmishes in Germany and the neighboring countries , p. 561ff digitized

- Heinrich Schreiber, History of the City and University of Freiburg im Breisgau , Volume 5, pp. 74ff digitized

- Bernhard Röse, Duke Bernhard the Great of Saxe-Weimar , volumes 1–2, p. 250ff digitized

Web links

Individual evidence

- ^ Lothar Höbelt: From Nördlingen to Jankau. Imperial strategy and warfare 1634-1645 . In: Republic of Austria, Federal Minister for State Defense (Hrsg.): Writings of the Heeresgeschichtliches Museum Wien . tape 22 . Heeresgeschichtliches Museum, Vienna 2016, ISBN 978-3-902551-73-3 , p. 10 .

- ↑ Theatrum europaeum, III. P. 1002.