Battle of Freiburg im Breisgau

| date | 3rd, 5th and 10th August 1644 |

|---|---|

| place | Area around Freiburg im Breisgau |

| output | draw |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

| Commander | |

| Troop strength | |

| 20,000 | 16,000 |

| losses | |

|

1100 |

6000 |

Wallerfangen - Dömitz - Haselünne - Wittstock - Rheinfelden siege - Rheinfelden battle - Breisach Siege - Witten Weiher - Vlotho - Ochsenfeld - Chemnitz - Bautzen siege - Freiberg sieges - Riebel Dorfer Mountain - Dorsten - Preßnitz - La Marfée - Wolfenbüttel siege - Kempen Heath - Swidnica - Breitenfeld - Klingenthal - Tuttlingen - Freiburg - Jüterbog - Jankau - Herbsthausen - Alerheim - Korneuburg - Totenhöhe - Hohentübingen - Triebl - Zusmarshausen - Wevelinghoven - Dachau - Prague siege

During the Thirty Years' War the battle of Freiburg im Breisgau took place on August 3, 5 and 10, 1644 . The battle, fought on three separate days, between the imperial and Bavarian troops under Franz von Mercy and the French under the marshals Duke von Enghien (later Ludwig II of Bourbon, Prince of Condé) and Turenne is considered to be one of the most loss-making of the whole War. Although the French suffered significantly higher losses than their opponents, they later claimed victory for themselves. However, the battle only cemented the status quo and ended in a strategic draw.

the initial situation

In order to prevent the French from invading Bavaria in the last phase of the Thirty Years War, Elector Maximilian I relied on a forward strategy. In 1644 he sent a Chur-Bavarian army under General Field Marshal Franz von Mercy with about 10,000 foot soldiers and with almost as many mounted men to the west. Under his command were the cavalry general Johann von Werth , the general sergeant Johannes Ernst Freiherr von Reuschenberg zu Setterich and the general witness Alexander von Vehlen . Mercy was preceded by the reputation of the victor in the battle of Tuttlingen , in which he had wiped out the Franco-Weimar army in 1643.

Recapture of the city of Freiburg

Since the conquest in 1638 by Bernhard von Sachsen-Weimar , the western Austrian region of Freiburg was occupied by French-Weimaran troops. When the enemy imperial army under Franz von Mercy approached , the Franco-Weimaran city commander, Colonel Kanoffski , ordered his government in Breisach to blow up the women's convents in the outskirts of the city and burn down all the grinding mills as well as the Lehen and the preacher suburbs. This meant that potential besiegers of the city could not hide in buildings in front of the city and the city commander was given a clear field of fire.

At the end of June, the Imperial Army began the siege to recapture Freiburg. All sacrifices and defense efforts of the population were in vain. The city had to surrender on July 27th. Mercy granted the brave crew an honorable deduction “in the classic manner with a sounding game, with flying flags, with a burning fuse and with a ball in the mouth”, i. H. ready to fight in the French fortress of Breisach .

During the fighting for the city ten kilometers south of Freiburg on the Batzenberg near Pfaffenweiler, a French-Weimaran relief army of 10,000 men under Marshal Turenne was located . This Armée de l'Allemagne was inferior to the imperial army that had besieged and captured Freiburg and was also shocked by the defeat at Tuttlingen. Therefore Turenne had not intervened in the battle for Freiburg and instead waited for his troops to be reinforced by the Armée de France under the command of Duke Enghien . This army had to move from Verdun, 250 km away, and did not arrive in Krozingen, the Turennes camp not far from Freiburg, until August 2nd, despite forced marches of up to 33 kilometers per day.

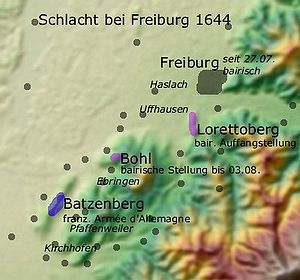

The fighting on the Bohl

With around 16,000 men, the French army, united under Enghien's command, was now about as strong as the imperial Bavarian troops. Without allowing the reinforcements that had been brought in to rest, the Duke attempted to take the strategically important Schönberg with a pincer attack on the afternoon of August 3rd . There the infantry regiments had holed up under the command of Baron von Reuschenberg, since his western branch, the Bohl, allowed control of the south-western access to the northeastern Freiburg. To bypass the Schönberg, Enghien let the Armée de l'Allemagne Turennes pull through the Hexental, while he himself advanced with the Armée de France from Ehaben in the direction of Bohl.

The starting position for the attacking French was extremely difficult; They had to storm a steep mountain, while the Bavarians over the Schönberg on relatively flat paths from the Hexental valley four kilometers to the east and their positions on the Schlierberg (today Lorettoberg ), two kilometers south of Freiburg at the northern end of the Hexental opposite the Schönberg and five kilometers as the crow flies east of the Bohl, were able to provide supplies.

Mercy's well-entrenched troops offered heavy resistance. The attackers suffered great losses. When it got dark, the fighters were often only a few meters away from each other halfway up. Mercy saw that he could no longer hold the position and that night withdrew his troops into reception positions on the Wonnhalde and Schlierberg. With this maneuver, the Bavarian escaped the pincer attack by the French, which Enghien wanted to continue on the morning of August 4th. The weather came to the aid of the Reich troops, because the French could not keep their powder dry, as a Bavarian war commissioner reported: " It was a cold, constant rain, which hurt the poor servants very much, but I think God sent him so that Enemy could not attack us until we had built (built entrenchments ) on the mountain . "

The decision on the Schlierberg

The Duke knew that Mercy would soon be forced to leave, mainly due to a lack of food for his horses, but he did not want to wait. After the weather had improved, he decided to pursue Bayern early on the morning of August 5th. Enghien again tried to deceive Mercy and initially attacked the Bavarian positions on the Schlierberg only with a vanguard of the Armée de France . At the same time he let the entire Armée de l'Allemagne advance from Merzhausen towards the Wonnhalde. Here the low morale of his troops, feared by Turenne, became evident. When they lost their Field Marshal Lechelle in the storming of the Bavarian entrenchments, they were thrown back by the imperial troops in a counterattack. Even a personal intervention by Enghien to strengthen the fighting morale only had the effect that the Bavarians did not pursue the French, but withdrew behind their entrenchments. In these bloody battles the French lost 1,100, but the Bavarians only 300 dead and wounded.

The attackers on the Wonnhalde, demoralized by the heavy casualties, were only good as flank cover when the decisive battle broke out on Schlierberg in the course of the afternoon. Again and again, Enghien's Armée de France troops ran up the western slope. The Bavarian artillery fired into the oncoming infantry from their strategically advantageous positions and all French attacks collapsed in the murderous fire of the muskets . In anger, the duke threw his marshal's baton among the fighting and drove new soldiers into battle with the shout of encore mille (another 1,000). At the fourth attempt, the French penetrated the Bavarian positions. Caspar von Mercy, brother of the field marshal and sergeant-general of the cavalry, recognized the distress of the foot troops. He had his cuirassiers and dragoons dismount and jump into the breach on foot with a bare saber .

Enghien then drove a fifth wave of attacks up the mountain. Then Franz von Mercy vowed to build the holy virgin a little Lauretan shark after the pattern of the Santa casa in Loreto on the Slierberg, if he succeeded in throwing back the enemy. In fact, the demoralized attackers backed away and left in the dark of night. It was not until 1657 that Christoph Mang, the guild master of the merchants, donated the Loretto Chapel , which was built on the site of the Joseph Chapel that had been destroyed in the fighting.

Friedrich Schiller wrote in his history of the Thirty Years War:

“The Duke of Enghien had to decide to retreat after slaughtering 6,000 of his people for free. Cardinal Mazarin [ Richelieu's successor ] shed tears over this great loss, which the heartless Enghien, who was only sensitive to fame, ignored it. 'A single night in Paris', he was heard saying, gives life to more people than this action killed'. "

The Bavarians lost around 1,100 men, the majority of whom were wounded.

Mercy was ordered to hold Freiburg and not pursue what the French took as an opportunity to claim victory for themselves. In fact, like many others in the Thirty Years War, the Battle of Freiburg ended in a draw.

Battle of St. Peter in the Black Forest

In the early morning hours of August 10, 1644, the opponents met again near the St. Peter monastery between Glottertal and Eschbachtal when Turenne tried to cut off Mercy's supply and retreat line. When the foot troops had already reached the plateau, the cavalry General von Rosens destroyed part of the train of Bavarian troops that was on the march in a narrow valley behind the foot troops. During an unsuccessful attack by the French on the Bavarian infantry, a successful attack by the Bavarian horsemen on the flank of the French formation drove them to flee through the narrow Eschbach valley. When the Bavarians refused Mercy's order to pursue the French troops, he withdrew because of the poor supply situation and reached Villingen, 70 kilometers away, on the same day .

Enghien broke off the pursuit of Mercy for the same reason, his troops initially rested in St. Peter and set the monastery on fire the next day when they withdrew.

Both armies moved north and east of the Black Forest, Enghien conquered the Philippsburg fortress . The next meeting of the two armies took place on May 5, 1645 in the battle of Herbsthausen .

Immediate impact on the population

The Swedish mercenary troops, notorious for their cruelty, had ravaged the region since 1638 and massacred the male population of Kirchhofen , 15 kilometers south of Freiburg. The victims were crushed alive to death in a wine press.

During the siege of Freiburg, the residents of the places around the Schönberg and Batzenberg were particularly hard hit. The 10,000 men of the Armée de l'Allemagne Turennes on the Batzenberg, including the entourage, had to be supplied, as did the even larger number of imperial troops in Freiburg. As is customary in the Thirty Years War, the armies essentially fed themselves by pillaging the surrounding towns. A concentration of troops in a region for several months meant scorched earth for several years and thus often the death of the rural population who survived the fighting and were deprived of their food reserves. After the arrival of the Armée de France Condés, in view of a troop concentration of 40,000 men in August 1644, the region was on the verge of being unable to supply the troops any longer, so that both armies had to seek a decision.

aftermath

On the Schönberg above Leutersberg and Ebringen the battle cross commemorates the battle on August 3rd. It stands in the place of an ossuary , in which the remains of the fallen were buried 30 years after the battle, scattered all over the mountain. The mass grave developed - not to the delight of the church - into a place of pilgrimage for the Catholic population in the region, and bones were apparently stolen again and again as relics. Since the church could not prevent the pilgrimages, the relatively few remaining bones of the fallen were finally transported away in 1791 at the instigation of the pastor and administrator Ildefons von Arx, who was appointed by the St. Gallen lordship in Ehaben , which led to the veneration of the place in the following decades Came to a standstill.

See also

literature

- Johann Heilmann : The Bavarian campaigns in 1643, 1644 and 1645 under the orders of Field Marshal Franz Freiherrn von Mercy . Verlag FW Goedsche'sche Buchhandlung, Leipzig / Meißen 1851, pp. 153–194 ( digitized version )

- Heinrich Schreiber : History of the city of Freiburg im Breisgau . Verlag Franz Xaver Wangler, Freiburg im Breisgau 1858, Volume 4, pp. 120-153 ( digitized version ).

- Philipp von Fischer-Treuenfeld: The reconquest of Freiburg by the Kurbaierische Reichsarmee in the summer of 1644 . Freiburg i.Br. 1895

- Hans Gaede : The campaign around Freiburg 1644 , Freiburg i.Br. 1910

- Hans-Helmut Schaufler: The battle near Freiburg im Breisgau 1644 . Rombach-Verlag, Freiburg 1979, ISBN 3-7930-0223-3 , 136 pp.

- Helge Körner (Hrsg.): The Schönberg - natural and cultural history of a Black Forest foothill. Lavori-Verlag, Freiburg 2006, ISBN 3-935737-53-X , 472 pages, 48 color plates and 200 b / w illustrations.

cards

- Les combats donnés devant la ville et chasteau de Friborg en Brisgau Vedute by Sébastien de Beaulieu

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Hans-Helmut Schaufler: The battle near Freiburg im Breisgau 1644 . Freiburg 1979, p. 75.

- ^ Friedrich Schiller : History of the Thirty Years War . Fifth book . Frankfurt / Leipzig 1792, p. 472