Battle of Alerheim

| date | August 3, 1645 |

|---|---|

| place | Alerheim , Bavaria |

| output | French-Weimaran-Hessian victory |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

|

Imperial Bavarian troops |

French-Hessian-Weimaraner troops |

| Commander | |

|

High command: |

High command: |

| Troop strength | |

| 15-16,000 men 29 guns |

6,000 French 5,000 Weimaraners 6,000 Hessen 27 guns |

Wallerfangen - Dömitz - Haselünne - Wittstock - Rheinfelden siege - Rheinfelden battle - Breisach Siege - Witten Weiher - Vlotho - Ochsenfeld - Chemnitz - Bautzen siege - Freiberg sieges - Riebel Dorfer Mountain - Dorsten - Preßnitz - La Marfée - Wolfenbüttel siege - Kempen Heath - Swidnica - Breitenfeld - Klingenthal - Tuttlingen - Freiburg - Jüterbog - Jankau - Herbsthausen - Alerheim - Korneuburg - Totenhöhe - Hohentübingen - Triebl - Zusmarshausen - Wevelinghoven - Dachau - Prague siege

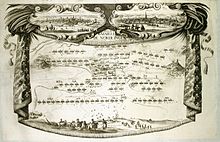

The Battle of Alerheim , often also called the Second Battle of Nördlingen , was a battle of the Thirty Years' War that took place on August 3, 1645 in and around Alerheim between the French- Weimaran- Hessian army and Bavarian - imperial troops and with a French-allied Victory ended.

A few weeks after the lost battle of Herbsthausen on May 5, 1645, a French army was sent from Alsace to Hesse under the command of the Duke d'Enghien , later Grand Condé , to reinforce the defeated French army under Marshal Turenne . This was to be followed by a new campaign against Bavaria. At Ladenburg the two French armies united with Hessian troops under General Geiß and the Swedes under Field Marshal Königsmarck from Moravia .

Field Marshal Franz von Mercy was again given the task of protecting Bavaria against an attack by this army, and he marched with an imperial Bavarian army to Heilbronn in order to be there before the enemy. In the meantime, the Swedes separated from the French-Allied army and went their own way. The armies followed one another in evasive fighting. The united French army succeeded in pushing the Bavarians back to the Swabian border . After a skirmish near Dinkelsbühl , both armies marched into the Nördlinger Ries . The French, together with the Hessians and Weimarans , arrived in front of Nördlingen on August 3, 1645 , while the Bavarians and Imperialists took up positions in and around Alerheim. The Duc d'Enghien decided, against the concerns of the generals under him, to accept the battle.

Despite the fierce resistance of the Bavarian troops, the united French-Allied army managed to take the village of Alerheim. After the right wing of the French was forced to flee by a violent attack by the Imperialists, led by General Werth , the French army under Condé and Turenne began a last, desperate attack on the right wing of the Imperialists. After heavy fighting, the French and their allies succeeded in routing the Bavarian left wing. The fierce battle was thus decided in favor of the Franco-German alliance.

Militarily, this battle was a Pyrrhic victory for France , which brought no decision as France was unable to advance further into Bavaria. However, this stalemate meant that the peace negotiations were ultimately accelerated and continued. The village of Alerheim was so badly devastated that its reconstruction was only finished after 70 years.

prehistory

France enters the war, alliance with Hesse and the Weimarans

When the Swedes were defeated in the Battle of Nördlingen , France entered the war on Sweden's side . This not only strengthened the Protestant war party, but also ensured its continued existence in the first place.

The Duke Bernhard von Weimar , also known from the Battle of Nördlingen , who was excluded from the line of succession as a later son, campaigned as a mercenary leader based on the model of Wallenstein for his own duchy, which he wanted to win by force of arms. For this purpose he had chosen Alsace, which until then had been a Landgraviate of Upper Austria. Richelieu was also interested in Alsace in order to push the French state border to the Rhine; In addition, Bernhard von Weimar's thirst for conquest came in handy.

On July 18, 1639, Bernhard von Weimar, who commanded his own armed forces, suddenly died in Neuenburg am Rhein of a puzzling fever. Immediately after his death, rumors surfaced that he had been poisoned. The rumors were fed by the numerous French negotiators who were present after his death and by the fact that the death of Bernhard was very convenient for Richelieu, who was in financial distress, as he was no longer able to dispute the numerous subsidy promises made by France out of taxpayers' money.

By sending troops and bribing Weimaran officers, Richelieu drew the entire army of Bernhard on his side. Sun's performance in October 1639 the army weimaranische the oath of allegiance to the King of France. The Weimaran troops now moved to Hesse under the command of two French generals and persuaded Landgravine Amalie to conclude a Hessian-French alliance. For this reason, the Weimaraner and the Hessians operated under French command in the following years.

The French were beaten repeatedly, however, and neither side gained excess weight in order to bring about a swift decision. So the war dragged on for years. Because of the general lack of money, the armies of all warring parties from the occupied countries had to support themselves. The consequences were arson , looting and the worst riots.

Campaign of the French Allied Army against Bavaria

Association of French and Allied troops in Hesse

Although the peace negotiations between the warring parties began in Munster as early as August 1644 , the fighting continued and the individual warring parties were still trying to gain advantages for themselves. After the French in August 1644 after the Battle of Freiburg , the Alsace had occupied the Bavarian-imperial troops tried to turn the tide again. On May 5, 1645, the French suffered a crushing defeat at the Battle of Herbsthausen.

The operations of the French Allied army under Marshal Turenne had suffered a serious setback on the German theater of war. Turenne retired to Hesse, where Count Konigsmarck , who commanded a Swedish corps, united with his army. In addition, the troops of Landgravine Amalie von Hessen-Kassel strengthened Turenne's armed forces.

Cardinal Mazarin , Prime Minister of the King of France, instructed the Duke of Enghien (later Prince Condé) and Marshal Count Gramont to march to Germany at the head of about 8,000 men to join Marshal Turenne's troops. Mazarin threatened that he would pull a superior opponent on Bayern's neck. After the union with the troops of Landgravine Amalie von Hessen-Kassel and with the contingent of the Swedish general Count Königsmarck, the army of Marshal Turenne comprised 14,000 men. Turenne marched from Friedberg in Hesse to Gelnhausen . When he had received news of the Duc d'Enghien's march to the Rhine and had received orders to unite with him, he crossed the Main between Frankfurt am Main and Hanau , turned to Bergstrasse, took the town of Weinheim and united near Ladenburg with the army of the Duc d'Enghien, who had crossed the Rhine near Speyer on June 19 .

The combined French-Hessian-Weimaran-Swedish armed force then had a combat strength of 22,000 men. The command of the Duc d'Enghien took over the command of Mazarins. His aim was to restore the fame of the French arms, which the Herbsthausen defeat had shaken. Duc d'Enghien, full of youthful zest for action, could hardly wait for the moment to compete with his opponent in open field battle.

Evasive maneuvers by the Bavarian Field Marshal Mercy

The Imperial Bavarian Army under Field Marshal Franz von Mercy marched from Aschaffenburg along the Main to Miltenberg , went here on the left bank of the Main and united on July 4, 1645 with the 5,000-strong corps (3,000 infantry and 2,000 cavalry) of the imperial General Geleen. Knowing that he had a numerically superior opponent in front of him, Mercy dodged again and again and withdrew, because he had recognized that the Duc d'Enghien was trying to win the Danube and thus Bavaria, which he prevented by his persistent manner of fighting sought. Not to allow the enemy to penetrate Bavaria was the directive of the Bavarian Elector Maximilian . From Amorbach , Mercy marched in forced marches towards Heilbronn in order to be there before the enemy, because he correctly assumed that the enemy had this fortress as their primary goal.

Deduction of the Swedish quota

The Duc d'Enghien actually turned to Heilbronn , at that time the most important Swabian fortress . Mercy, however, got ahead of him through his foresight and his forced march there. He appeared completely unexpected for the Duc d'Enghien on the right bank of the Neckar on a conveniently located hill, a vineyard between Heilbronn and Neckarsulm , in order to defend Heilbronn with his entire force. He arrived an hour before the French. Only the cavalry of the French-Allied army had arrived at Heilbronn and had to wait for the infantry to arrive .

After he could not do anything there, Duc d'Enghien decided to turn to Wimpfen . Marshal Count Gramont was chosen for this task. His detachment should consist of contingents from Hesse, Sweden, Weimaraners and French. However, there were differences of opinion among the generals about how to proceed strategically. The Hessian general Geiss and the Swedish general Graf Königsmarck had already expressed in Ladenburg that they did not want to induce Mercy to throw himself between the Allied army on the one hand and Franconia and Hesse on the other and cut them off from the important supply routes.

The consultation was evidently violent. An insult which the arrogant Duc d'Enghien was guilty of against Generals Geiss and Königsmarck resulted in their separation from the Allied army. With great effort and persuasion Turenne succeeded in persuading Geiß and his Hessians to stay. At the same time, Landgravine Amalie von Hessen-Kassel was asked by couriers to leave her Hessian contingent with the army. The Hessian General Geiss agreed to remain with the united army until the reply from his sovereign was received. However, the Swedes could no longer be held and did not take part in the later battle of Alersheim.

For the Weimaraners, the question arose whether to stay or not to leave, since they were sworn in to the King of France. After the withdrawal of the Swedes, the Allied army consisted of about 6,000 French, 5,000 Weimarans and 6,000 Hessians each; so altogether about 17,000 to 18,000 men with a total of 27 guns. In contrast, the strength of the Imperial Bavarian Army was 15,000 to 16,000 men with 29 guns.

After the withdrawal of the French-Allied army and the conquest of Wimpfens by the French on July 8, 1645, Field Marshal Mercy foresaw that the Duc d'Enghien would turn to Schwäbisch Hall ; he got ahead of this operation by marching over Weinsberg , Löwenstein and Mainhardt . At Schwäbisch Hall he put his armed forces in order. The French-Allied army withdrew to Mergentheim and then against Rothenburg ob der Tauber . On this march, Duc d'Enghien set fire to most of the villages the army passed, as the residents were accused of slaughtering a large number of dispersed French after the Battle of Herbsthausen, which Turenne lost on May 5, 1645.

Rothenburg surrendered to mercy and disgrace on July 18 after a heavy cannonade. 200 defenders were forced into the French armed forces and the armed citizens were treated badly. A significant supply that the army urgently needed fell into its hands. The Allied army received its regular supplies in several convoys from Würzburg . In April 1645 Rothenburg had already been taken by Turenne's troops. Duc d'Enghien's expectation, however, that Mercy would rush to protect Rothenburg with his armed forces and take part in battle, was not fulfilled. Duc d'Enghien stayed in the city for a few days and then took up a position at Hollenbach and Schrozberg .

The Bavarian Imperial Army left a garrison in Schwäbisch Hall and withdrew with their main force via Talheim , where Mercy had set up his headquarters on July 18th, to Crailsheim and on July 24th to Feuchtwangen , “... in order not to think of it alone To cover Dinkhelsbüll, but also to preside over Feint, and that he shouldn’t deny us the lead over the Danube to prevent so much humanly ... ” Mercy moved about 600 men from Feuchtwangen on July 30th under Colonel Creutz to the city of Dinkelsbühl .

Skirmishes near Dürrwangen an der Sulzach

D'Enghien now turned against Dinkelsbühl and had preparations there made for the siege of the city. Before midnight, Turenne received news from an officer who had escaped from Bavarian captivity that Mercy was marching to the Danube - he was marching south with his army in a forest area. Turenne discussed with the Duc d'Enghien. He gave orders to leave the entire baggage and two or three regiments of cavalry behind, to break off preparations for the siege at once, and to march towards Mercy.

During the same night, both armies crossed an extensive wooded area near Dürrwangen an der Sulzach without knowing each other . The Bavarian Imperial Army had a small head start and, moreover, received news of the presence of the enemy earlier. Thus she was able to form a battle order in great haste when leaving the forest at dawn on August 1, 1645 - so skilfully behind ponds that the French could not attack when they left the forest. The Duc d'Enghien then also set up his army in order of battle and they fired at each other with cannons and muskets . Only narrow paths, on which no more than two men could walk side by side, ran between the fronts and everything that showed up was taken under murderous fire. Duc d'Enghien himself was also in great danger when he dared to venture forward on one of these routes to explore personally. After the two armies had faced each other for several hours without one being able to attack, and after the mutual bombardment had cost several hundred deaths (the Theatrum Europaeum reports 200–300 deaths on both sides), Condé gave the order at one o'clock at night, move away and march past Dinkelsbühl to Nördlingen .

Mercy initially assumed that Condé would besiege Dinkelsbühl. But in order to obtain final certainty, he drew up an order of battle near Sinbronn , from where he could see both the city and the enemy. So he was able to convince himself that Duc d'Enghien was passing Dinkelsbühl.

The Duc d'Enghien took the route to the Danube via Nördlingen. On the morning of August 3, 1645, the entire French-Allied army had arrived at the gates of Nördlingen. Now this city was to be taken, where Mercy had sent a Bavarian crew of 300 musketeers from the regiment Gil de Hasi under Lieutenant Colonel Beltin from Dürrwangen . Mercy and his army were on a more easterly route via Oettingen to the Danube.

Course of the battle

Preparations for battle of the Bavarian Army

Coming from the forest near Dürrwangen, where the two armies had faced each other, the imperial Bavarian army moved via Wassertrüdingen and Oettingen in the direction of Donauwörth , in order to block the enemy from entering Bavaria on the instructions of Elector Maximilian. Condé had chosen Nördlingen as a temporary destination because he promised rich booty there and because this city was on his way to the Danube. When Field Marshal Mercy arrived at Alerheim at the head of his army on the morning of August 3, 1645, he recognized the terrain formation, which was extremely favorable for a battle, and decided to set up his army here for battle. The units were briefed in their positions and had to start digging work immediately. Mercy sent the entourage to Donauwörth and across the Danube in order to be more agile with the army.

On the right wing , where General Graf Geleen commanded, eleven squadrons of the imperial cavalry regiments Kolb , Caselny , Geiling , Hiller , Holstein and Croats with seven guns, the first and six squadrons of the cavalry regiments Kolb, Stahl, Hiller and Holstein, held the position in the second meeting . The Wennenberg itself was occupied with five guns by the infantry regiments Mandelsloh and Plettenberg .

In the center, from where Field Marshal Freiherr von Mercy was in command, the foot regiments Henny , Gorv , Mercy , Gold , Halir , Kolb and Royer stood at the first meeting to the east behind Alerheim ; they were armed with three guns. The fortified village itself, where General Feldzeugmeister Johannes Ernst Freiherr von Reuschenberg zu Setterich (also called Reischenberg or Rauschenberg) was in command, was defended by seven battalions with six guns.

The Bavarian cavalry general Johann von Werth led the left wing, which leaned on the left against the castle ruins occupied by two battalions and three guns. This wing consisted of 16 squadrons, of which eight of the cavalry regiments Werth , Fleckenstein , Sporck , and Lapierre with four cannons were posted in the first and eight squadrons of the regiments Salis , Werth , Flechst , Sporck , Dragoons and Lapierre in the second meeting. One squadron of dragoons and one squadron of riders from the Lapierre regiment had occupied the Steinberg (vulgo Spitzberg) in order to prevent the imperial-Bavarian front from being surrounded from the south. In the north, i.e. to the right of the imperial position, this was not to be feared because of the Wörnitz flowing not far behind .

The entire imperial-Bavarian position was provided with entrenchments . In the village Alerheim were in the houses loopholes broken and been uncovered roofs. Trees in the gardens had been felled and walls torn down to create a clear field of fire. The order of battle that Field Marshal Mercy had chosen was based in the village of Alerheim, a forward bastion between the two wings . Neither of the two wings could be attacked without the attacker having received flank fire from the village, but also got caught in the crossfire when advancing further from the two hills and from the village.

Preparations for battle of the united French army

Portrait of David Teniers the Elder J.

Duc d'Enghien was in the field camp outside Nördlingen when a Swedish scout brought the news that Mercy was preparing for battle at a nearby place. At first the Duc d'Enghien did not want to believe this news, as Mercy had so far always avoided a direct dispute because he knew that he was outnumbered by the French-Hessian-Weimaran army. After having convinced himself of the correctness of the representation from the nearby hill, he rode under the protection of a few squadrons with the Marshals of France and the other generals of his army in great haste out to Alerheim, where the Imperial Bavarian Army had taken an extraordinarily favorable position. Everywhere there was digging to improve the already naturally very advantageous position.

The Duc d'Enghien and his generals rode very close to Mercy's Alerheimer position to investigate the situation and held a council of war under a group of plum trees. There were discussions between the Duc d'Enghien and his generals as to whether it would make sense at all to attack this excellent position of the Imperial and Bavarians. Even Marshal Turenne advised against an attack. He said that one could not give a battle to the enemy so positioned without subjecting the French army to an almost certain defeat. The youthful and energetic Duc d'Enghien, however, decided against all the reservations of the seasoned generals for the battle for which he had long waited.

Since the wings could not be attacked because of the flank effect of the village, the village first had to be attacked head-on, while the two wings should advance at the same height. But here too there were different views in the War Council. Turenne's opinion that the two wings should remain at the height of the village while the infantry were busy conquering the village was then accepted by the Duc d'Enghien. In this way the entire imperial-Bavarian order of battle was to be shaken. The Duc d'Enghien apparently consciously accepted an impending massacre, since he had to assume that the village was heavily occupied and well prepared for the defense.

The Duc d 'had also considered attacking and rolling up the position of the Bavarians and Imperialists from the flank , that is, over the Spitzberg and the castle. This should take advantage of Mercy's position. He evidently abandoned this idea - probably in consultation with his generals - and nevertheless chose the frontal attack .

The French-Hessian-Weimaran army marched on the plain in front of Alerheim. Field Marshal Chastelux had the task of instructing the units as they approached in the direction of their future position. The infantry received the Alerheim church tower as the direction of march. Chastelux, who only had a small escort with him, was killed in a skirmish with Bavarian light riders and infantrymen roaming the plain. Castelnau therefore took on his task. At about four o'clock the army was drawn up. Bayern did not show up.

The right wing of the Franco-Weimaran-Hessian army consisted mainly of the French cavalry under the command of Marshal Graf Gramont. Six escadrons of the French Guard, Carabiniers and the regiments Fabert , Wall and Anguien with four guns stood in the first meeting and four escadrons of the Regiment Gramont , La Claviere , Boury , Chambre and Gramont in the second line. The French right wing reserve, under the command of Marshal Chabot, was formed by two escadrons from the Neu-Rosen regiments, four battalions of infantry, Trousses , Irlandais , Fabert and the Garrison de Lorraine . To the right of it stood two escadrons from the Marsin Cavalry Regiment .

The left wing was commanded by Marshal Turenne. In the first line the order of battle was formed from six squadrons of the Weimaraner cavalry regiments Roßwurm, Mazarin, Tupadel, Tracy and Turenne with nine guns, in the second meeting four squadrons of the Weimaran cavalry regiments Alt-Rosen , Fleckenstein and Kanofsky went. The left wing reserve consisted of Hessian troops under General Geiß. They were the cavalry regiments Oehm, Albrecht von Rauchhaupt and Michael de Schwert under Colonel Oehm. This was followed by the six Hessian infantry battalions Frank, Lopez de Villa Nova, Uffel, Wrede, Stauf and Kotz von Metzenhoven. Then six squadrons from the cavalry regiments, Baucourt, Groot and Leibregiment Geiß followed to the right.

In the center, which was under the command of General Count Marsin, infantry was formed, consisting of seven battalions from the French regiments of Bellenave, Oysonville, Mazarin, Conty, d'Anguien and Persans with 14 guns in the first meeting and three battalions in the second line the regiments of Gramont, Haure and Montausier. Behind it were three cavalry regiments of Carabiniers.

As was customary at the time, the artillery was mostly in front of the front or in such a way that its own troops did not have to be overshot if possible. This placement of the artillery led to high losses and the unpopularity of this type of weapon. It was therefore mostly recruited from unreliable people like horse thieves and those who had to atone for other offenses and had to prove themselves.

French infantry attack the village of Alerheim

Between four and five in the evening the battle began with an artillery duel, in which the imperial-Bavarian artillery, which could fire from well-developed positions, had the advantage. The French-Allied artillery first had to pull up, turn around and bring the guns into position, with the Imperial-Bavarian artillery already firing their salvos and severely hampering this.

General Marsin was ordered to attack the village with his infantry. The assault reached the western edge of the village, but was repulsed by the murderous fire of the defenders, so that the attackers had to retreat with great losses. General Marsin himself was badly wounded. Thereupon the Duc d'Enghien ordered the Marquis de la Moussaye to take up the retreating troops of the first attack wave at the head of a few fresh battalions and to carry out a new attack. However, even the marquis did not succeed in breaking in decisively. The Duke, aware of the importance of this offensive operation, withdrew infantry units from the right wing, much to the displeasure of Marshal Gramont, who protested against it at the Duc d'Enghien, put himself at the head of the forces and led them against what was doggedly defended Village where the Bavarians shot out of their fortified houses and positions and caused heavy losses among the French.

During these stubborn frontal attacks by the French, Field Marshal Mercy assumed that the strength of the French army would break at Alerheim. Nevertheless, he had to constantly deploy reinforcements in the village, which he withdrew from the Wennenberg or from the right wing and personally led to the focus of the action.

Duc d ', who ventured into the middle of the battle in the village, lost two horses among himself and was shot at the breastplate and at his clothing. But then what happened that gave the battle the decisive turn: Field Marshal von Mercy fell dead from his horse, hit in the head by an enemy musket ball. The French had reached the western edge of the village, had thrown fire torches according to orders and set some thatched roofs on fire. The village, which consisted mostly of thatched houses, went up in flames. Because of the heat that the fire spread, the defenders had to withdraw from the village. The Bavarians only offered resistance in the cemetery, in the church and in two stone houses.

Attack by the Bavarian cavalry on the French right wing

Meanwhile, Bavarian infantry attacked the French cavalry units from the Schlossberg. To repel this attack, Marshal Gramont had his second line, the infantry regiments Fabert and Wall , advance. This developed into a skirmish, so that Gramont was forced to intervene. He received a musket shot on his helmet, so that he sank unconscious on the neck of his horse. But the bullet hadn't penetrated. Gramont soon came to and was able to resume his leadership role.

While the fighting in the village had subsided because of the fires, the fighting continued below the castle hill. Johann von Werth undertook a daring attack with his Bavarian cavalry. He crossed the trench, which had been declared impassable by a French officer patrol, and rushed into battle against the French cavalry. This was extremely surprised and taken by surprise and partially forgot the defense, after all, she had been sure that she could not be attacked because of the impassable terrain. General Johann von Werth and his Bavarian cavalry overturned the entire right wing of the French - the French cavalry fled in unsubstantiated flight without being available to any order.

Gramont tried to save the situation and sat at the head of the two Irish regiments, Fabert and Wall , which had not left their positions and who fired salvos at close range against the Bavarian cavalry, so that the oncoming squadrons cleared. But this last resistance was also broken. Gramont got into a hand-to-hand battle. Surrounded by the few who remained loyal to him, Gramont found himself trapped on all sides. Four Bavarian horsemen, who were arguing over who he should belong to as a prisoner, prepared to kill him. Gramont's captain of the guards killed one of these riders and his adjutant killed another. At that moment Captain Sponheim of the Bavarian Lapierre regiment heard the name of Marshal von Gramont. He summarized a few officers who freed Gramont from the hands of the Bavarian riders and thus saved his life. Most of his guard had been killed. Marshal Gramont was taken prisoner.

On their flight, the French cavalry tore two Hessian infantry battalions away with them. Even the French reserve corps under Marshal Chabot could not stop the impetuous attack. Chabot initially succeeded in reassembling his reserve corps behind the Hessians, who were in the second line of the left wing, but was overrun there too and after a short time, being carried away by the fleeing squadrons of the first line, was also in flight . The reserve corps under Chabot was also completely wiped out.

In the momentum of his attack, Johann von Werth failed to attack the Hessian reserve corps that later rode the decisive attack on the Wennenberg. That was Johann von Werth's first serious mistake in this battle. Instead, he continued, carried away by impetuous Hot Streak, the attack to the convoy of the enemy gone, the south-west of Deiningen stood beyond the Eger. The margravial regiment left to cover it also fled. As was common at the time, the Bavarian riders began to plunder the French train extensively. In addition, they captured many flags and standards as well as artillery and other war material during this memorable cavalry attack . The French army suffered a heavy loss in the defeat of the right wing. Most of the dead cavalrymen were young nobles.

D 'and Turenne's decisive attack on the Wennenberg

D'Enghien's center was bled to death from the repeated and costly attacks and was no longer operational. Its right wing had been completely flattened and swept from the battlefield. The Duc d'Enghien now put everything on one card. He rode over to Marshal Turenne on his only left wing still intact. Both discussed briefly. Then at about seven in the evening the decision to attack the Wennenberg followed. Duc d'Enghien used his last reserves, although far from his home country. It was a militarily dubious and dangerous undertaking.

Turenne supported the Hessian and Weimaraner troops. With great losses, the Weimaraners came to the Wennenberg, which was then unforested. Field Marshal Mercy had withdrawn some squadrons from the imperial garrison of the Wennenberg and the right wing at the start of the battle and threw them against the French attackers in the village. Their absence was now making itself felt on the right wing. A dogged and loss-making fight developed on the Wennenberg. After changing battle advantages several times, Turenne and his Weimaran riders succeeded in breaking through the position of the imperial. The Imperial General Geleen rushed to the rescue at his second meeting and ripped up some Weimaran squadrons. The defenders seemed to be getting the upper hand. The Weimaraner attack was repulsed and the attackers went back down the Wennenberg.

Then the Duc d'Enghien himself seized the imperial position at the head of the Hessian regiments, the cavalry under General Geiss, Colonel Oehm and under Landgrave Ernst von Hessen-Kassel, as well as the infantry under Uffeln, the very last reserve he had left on. He picked up the retreating Weimaraners on his way uphill and came to the place of the fighting on the Wennenberg.

When the ammunition ran out, there was a scuffle. Since the imperial cavalry was now only one line deep, they no longer had any support from a second line where intrusions occurred. Therefore, the breakthrough was a disaster. The Hessians and the Weimaraners, now in the majority, cut down the imperial infantry regiments Mandelsloh and Plettenberg and captured the entire imperial artillery, which could no longer be brought to safety, as the carters had previously gone through with the horses and the limbs. A number of Bavarian riders were caught in this escape movement and hunted back to Donauwörth. General Geleen was wounded and taken prisoner. The imperial colonels Count Holstein and Hiller, as well as the Bavarian colonels Royer, Stahl and Cobb were also captured.

End of the battle, withdrawal of the Imperialists

From the left wing of the Allied army a new order of battle arose, which touched the village of Alerheim on its right and extended to the Wörnitz on its left. From this position the Bavarian front should be rolled up in a southerly direction. The refugees, now mainly the troops of the imperial Bavarian center, were persecuted mercilessly. A French battle report reports that, on the orders of Duc d'Enghien, the French pursued the enemy for two hours without taking anyone prisoner, except officers.

The Hessian Major Franke was commissioned with his brigade to clear the village of the enemy. But he was trapped east of the cemetery by two Bavarian cuirassier squadrons who had returned from Deiningen and his unit was completely wiped out. Major Franke and most of his men fell.

While the bitter battle for the Wennenberg was still going on, around eight o'clock in the evening Johann von Werth returned to the battlefield at the head of his victorious cavalry. It resumed its original position in order to proceed from there to the north against the enemy, but thereby reinforced the retreat movement of the right wing and the center even more. Had he stabbed the Hessians and Weimarans in the back, who at that time were still involved in bitter hand-to-hand fighting on the Wennenberg, he could have given the course of the battle a new twist. This was Johann von Werth's second and ultimately decisive mistake. Werth apologized with the falling darkness and the poor visibility through the smoke. He also found out of Mercy's death on his return to the battlefield. He gave up the battle, which through resolute intervention could have turned into victory. As the senior and highest ranking general, Werth took over the command and gathered his troops for the retreat near the Alerheim castle ruins. The Gil de Hasi regiment , which had occupied the churchyard and had fought in the defense of the village until then, surrendered to mercy and disgrace. At about one o'clock in the morning Johann von Werth led the remaining troops to Donauwörth .

After the battle, the French-Allied army camped north of the village in the cemetery, near Wennenberg and “on the plain”. The foot troops, some of which had advanced, were no more than 50 paces apart. Turenne followed Werth the next morning with 300 riders (according to the Theatrum Europaeum 1000 riders) until he saw Donauwörth. But he had to turn back because the Bavarian position on the Schellenberg , which still came from the Swedish army, was too strong for a promising attack and he would have needed infantry. Turenne had Harburg Castle occupied for this. Werth later had to accept the reproach from the Elector that he had not had Harburg Castle occupied on the way to Donauwörth.

losses

As a result of the repeated relentless frontal attacks by both sides, the Alerheim battle was a very bloody meeting, even by the standards of the time. Realistic figures cannot be clearly determined, however, as the reports glossed over their own losses and put those of the opponent higher than they actually were. The official loss figures of the French for the battle amounted to 4,000 dead and 2,000 prisoners for the imperial, while the own losses on the imperial side are given with a maximum of more than 1,000 dead and prisoners. While the French side only wants to give the French around 1,500 dead and wounded, Imperial General Werth speaks of 5,000, without the many wounded.

Since the French were completely defeated on their right wing, but attacked very solid positions in the center and on the left wing, it is likely that the far greater losses were on their side. And so Marshal Turenne estimates the losses of the French greater than those of Bavaria. The French infantry would have lost 3,000 to 4,000 men alone.

In German literature, Wilhelm Schreiber gives in Maximilian I, the Catholic, Elector of Bavaria and the Thirty Years' War, the losses of the imperial with 4,000 dead, those of the French with 5,000 dead. These numbers are also mentioned by Anton Steichele in: Das Bisthum Augsburg from 1865. The infantry of the French and his allies had been wiped out to a strength of 1,500 men and almost the entire mounted nobility had fallen under Marshal Gramont.

The Theatrum Europaeum gives 3,000–4,000 dead and 1,500–2,000 prisoners on the imperial side, on the French side 3,000 dead and a large number of wounded. In Christoph von Rommel, Geschichte von Hessen, the losses on both sides are given as 2,000 dead and 4,000 wounded.

In 2008, archaeologists found a mass grave with 50 skeletons where the French's right (almost completely worn) flank used to be.

Direct consequences of the battle

French side

After the victory, which had been won with heavy losses, the battered French-Weimaran-Hessian army moved to Nördlingen, ten kilometers away, with which it concluded a neutrality treaty in order to get urgently needed supplies there.

Then the French-Allied army moved in front of the city of Dinkelsbühl, which they besieged and captured. On August 18, the 25-man crews from Harburg Castle and Lierheim Castle were ordered back to Dinkelsbühl. Then the army withdrew from there to Schwäbisch Hall in order to regroup and regroup. As agreed, the Hessians separated from the Franco-Weimaran army.

The Duc d 'fell seriously ill with a Ruhr-like fever and was carried to Philippsburg in a litter. Marshal Turenne took command.

Because of the condition of the army, they wanted to get closer to the Neckar and the Rhine, also to get some money to pay the officers. The united army then moved via Weinsberg before Heilbronn , where the Bavarians had a garrison of a thousand men under the command of Colonel Fugger and where he threw some infantry. They saw themselves in no position for a siege and camped around this place for eight or ten days to wait for a few convoys from Philippsburg and money. When all this had arrived, the army advanced through the County of Hohenlohe with the intention of going into winter quarters in Swabia and for this purpose pushing the enemy's army back to the Danube.

Imperial side

The Bavarians and the imperial camps initially camped at Berg and then crossed the Danube at Donauwörth after the baggage had passed the Danube in a long column of cars all night long. They too needed a break and reinforcement. In particular, however, the Imperial Bavarian Army also needed the replacement of the lost artillery material, the largely missed powder and the musket balls. The captured French Allied officers, including Marshal Count Gramont, were brought to Ingolstadt the following day . The body of Field Marshal General von Mercy was carried on an artillery car.

Alerheim

The battle of August 3, 1645 was a catastrophe for the village. The attackers had thrown incendiary flares when they reached the first houses on the western edge, so that most of them went up in flames. The place remained destroyed for a long time and the reconstruction of the village was only finished after 70 years.

Further developments

The military situation changed again in favor of Bavaria when Archduke Leopold Wilhelm of Austria set out in Hungary at the urgent request of Elector Maximilian with 5,000 riders. He crossed the Danube and united with Geleen's armed forces, which had since been exchanged. Geleen had taken over the command. Johann von Werth and Baron von Reuschenberg reported to him. Turenne was unable to cope with a strengthened enemy force because of the heavy losses of Alerheim. The lossy victory was more like a defeat. When Turenne learned of the union of his opponent with the Archduke, he and his army fled almost immediately to Wimpfen, where there was still a French garrison, and from there back over the Neckar. The French then headed for the Rhine in great haste. Turenne could not cross this without a bridge. He therefore holed up with his Weimaraners and held out until a bridge was built. First of all, the entourage of Gramont's army part crossed the Rhine.

In the meantime, the Imperial Bavarian troops recaptured all the places that the French had taken in the months before. When Turenne had also withdrawn across the Rhine, the military situation again corresponded to that when Condé had arrived on the German theater of war four months earlier. The result of the Battle of Alerheim was neither militarily decisive nor did it have decisive political consequences.

In 1646, the combined French and Swedish troops advanced again to Bavaria. As a result, Elector Maximilian had to conclude the Ulm armistice with France, Sweden and Hesse-Kassel in March 1647 . After the elector took up arms again in September, a Franco-Swedish army devastated Bavaria again in 1648, only ended by the Peace of Munster on October 24, 1648.

literature

- Abelinus, Johann Philipp and Merian, Matthias: Theatrum Europaeum , Volume V, pp. 784–786

- Aumale Duc de: Histoire des Princes de Condé , Volume IV, Paris 1886, pages 427-444, 656, 658.

- Barthold: Johann von Werth , Berlin 1826.

- Beaulieu, Sébastian de Potault, Sieur de: Les glorieuses conquestes de Louis le grand, Roy de France , Volume I, p. 314: Large representative battle plan from 4 sheets, Paris 1676.

- Bourbon, Louis Joseph de: Essai sur la vie du grand Condé, par Louis Joseph de Bourbon, son quatrième descendant , London 1806.

- Buisson: The Life of Turenne , Amsterdam 1712.

- Chéruel: Lettres du Cardinal Mazarin pendant son ministère , Volume II, pp. 211 ff., Paris 1879/1887.

- Desormeaux: Histoire de Louis de Bourbon II, Prince de Condé , Paris 1748.

- Coste: Histoire de Louis de Bourbon II, du nome Prince de Condé , Volume I, pp. 72–77, Cologne 1695.

- Deschamps: Mémoires des deux dernières campagnes de Turenne en Allemagne , 2nd edition, 1756.

- Gramont, Antoine Charles Duc de: Mémoires du maréchal de Gramont , 2nd edition, Volume 1, pages 152–165, Amsterdam 1717.

- Grimoard: Mémoires du maréchal de Turenne , 1643 - 1659, Paris 1782.

- Guth Paul: Mazarin , Frankfurt 1974.

- Heilmann, Johann: The Bavarian campaigns in 1643, 1644 and 1645 under the orders of Field Marshal Franz Freiherr von Mercy , Leipzig and Meißen 1851.

- Herm, Gerhard: The rise of the House of Habsburg , Düsseldorf, Vienna, New York 1991.

- Kiskenne et Sauvan: Bibliothèque historique et militaire , Volume IV, Turenne, pages 401–403, 1846.

- Kraus, Andreas: Maximilian I., Bavaria's great elector , page 274-276, Battle of Alerheim and its immediate political and diplomatic consequences, Graz, Vienna, Cologne 1990.

- Marichal, Paul: Mémoires du Maréchal de Turenne , Volume 1, Paris 1909.

- Mercurio Vittorio Siri, royal. French historiographer: Del Mercurio overo Historia del corrente tempi , Volume V, page 2 and page 257–266, Paris 1655.

- Merian, Matthias: Topographia Svevia , Frankfurt on Mayn 1643/54.

- Misterek, Kathrin: A mass grave from the battle of Alerheim on August 3, 1645 , in: Report of Bayerische Bodendenkmalpflege , 53, 2012, pages 361–391.

- Napoleon I .: Depiction of the wars of Caesar, Turennes and Frederick the Great . German translation edited by Hans E. Friedrich. In volume 2, pages 213-217 report on the battle of Nördlingen (Alerheim). Sketches on pages 214 and 215, Darmstadt / Berlin 1942.

- N. N .: Les batailles mémorable des Francois, depuis le commencement de la Monarchie, jusqu'à present , Volume II: Battle of Noertlinguen (Alerheim), page 196–206, Paris 1695.

- N. N .: Prospectus from the former Schloss Allerheim im Ries, along with a thorough narration of the very bloody main meeting that fell on August 3, 1645 , reprint from the Theatrum Europaeum with changed punctuation, Oettingen, Lohse, end of the 18th century.

- N. N .: Battle of Allerheim on August 3, 1645 , Schnellpressedruck E. Litfaß, Berlin, Adlerstrasse. 6th

- Reichenau von, General of the Artillery: Battlefields between the Alps and the Main , Munich 1938.

- Riezler, Sigmund: The Battle of Alerheim , August 3, 1645. Separate print from the meeting reports of the philos.-philol. Class of the Royal Bavarian Academy of Sciences, Book IV, Munich 1901.

- Riezler, Sigmund: History of Baierns , Volume 5, Pages 583-589, Gotha 1903.

- Rommel, Christoph von: History of Hesse , battle report in Volume VIII, pages 682–684.

- Scheible, Karlheinz: Lecture given on the occasion of the 350th anniversary of the Battle of Alerheim, on August 3, 1995, in: 28th year book of the Historical Association for Nördlingen and the Ries , page 265–275, Nördlingen 1996.

- Scheible, Karlheinz: The battle of Alerheim, a contribution to the history of the Thirty Years War , self-published by Karlheinz Scheible, 2004, ISBN 3-00-014984-8

- Schreiber, Wilhelm, royal. Bavarian court chaplain: Maximilian I, the Catholic, Elector of Bavaria and the 30 Years War , Munich 1868.

- Steichele, Anton: The Diocese of Augsburg, described historically and statistically , third volume, Augsburg 1872

- Teicher, Fr .: Johann von Werth , 1876.

- Wedgwood, CV: The Thirty Years War , London 1938. The 30 Years War, Munich 1965/1993.

- Weng, Johann Friedrich: The battle of Nördlingen and siege of this city in the months of August and September 1634 . I. Addendum: “Further participation of the city of Nördlingen in the sufferings of the Thirty Years War.” From page 195–210 Short report on the Alerheim battle and its consequences for Nördlingen. (Riezler: With a lot of wrong information), Nördlingen 1834. New edition with the same title, Nördlingen 1984.

- Wild, Friedrich Karl: Philipp Holl or Six Trübsale and the Seventh , 1853. Holl was an eyewitness to the battle of Alerheim. The source is biographical records from the years 1596–1656 by Pastor Philipp Holl, which have been lost. New edition under the title “Nevertheless evangelical” by Pastor JG Ozanna

Archive sources (unprinted)

- Bavarian Main State Archives, (BayHStA), Kurbayern, Outer Archives (K ÄA)

- Volume 2275, page 154: Relation to the second battle of Nördlingen, which happened on August 3 / July 24, 1645. (Hessian battle report).

- Volume 2747, pages 32–42: Relation about the battle of Alerheim. German translation of a French original.

- Volume 2747, page 53: Relation. Probably Maximilian's report to the emperor on the battle of Alerheim.

- Volume 2747, page 22: Justified summary relation. (Official Bavarian battle report).

- Volume 2805, page 100: Maximilian to Geleen, with instructions that those guilty of the flight of the cavalry of the right wing should be brought to court martial. The judgment is to be carried out regardless of person. August 16, 1645.

- Volume 2806: well- founded summary relation, Donauwörth, August 4th, 5th and 7th, 1645.

- Volume 2819: Mercy's letter to Elector Maximilian dated July 24, 1645 from Feuchtwangen.

- Volume 2819, page 429: Letter from Elector Maximilian to Mercy with the instruction not to let the French have a head start on the Danube. Munich, August 2, 1645.

- Volume 2819 Ste. 437–442: " Justified summary relation." Report on the Alerheim battle.

- Volume 2819 Page 446: Johann von Werth to the Elector. August 4, 1645 from Donauwörth.

- Volume 2819, page 456: Maximilian confirms Johann von Sporck's oral report on the Alerheim battle.

- Volume 2819, page 457: Reischenberg's report on the dead and wounded from Alerheim. Donauwörth, August 7, 1645.

- Volume 2819 Pages 549 and 475: Maximilian to Werth and Ruischenberg: "Those who had manquered were to be judged within 8 days according to martial law and the sentence to be carried out without regard to the person." August 8 and 16, 1645.

- Volume 2819, page 477/479: Letter of condolence from Maximilian to Mercy's widow. August 9, 1645.

- Volume 2819, page 488: Johann von Werth to Elector Maximilian. Sent by Count Salm, together with the captured flags and standards. Donauwörth, August 7, 1645.

- Volume 2819, page 499: Justification of Johann von Werth and Ruischenberg to Elector Maximilian for not occupying Harburg after the Battle of Alerheim. August 9, 1645.

- Volume 2819 Page 532: Johann von Werth's apology for plundering Donauwörth.

- Volume 2822, pages 297-299: 1. Report by the war commissioners Schäffer and von Starzhausen to Maximilian about the Alerheim battle. Donauwörth, August 3, 1645, at night, after eleven o'clock.

- Volume 2822, page 307: 2nd report by the war commissioners Schäffer and von Starzhausen to Maximilian about the Allerheim battle. Donauwörth, August 4, 1645, 5 a.m.

- Volume 2822, Pages 310-312: 3rd report from the war commissioners to Maximilian from Donauwörth. 4th August 1645.

- Volume 2828, page 33/175: Maximilian to Geleen. He expresses his satisfaction that martial law has been held on the guilty officers. The execution should not be delayed on November 10, 1645.

- Volume 2828, page 177 ff .: Letter from the Bavarian Colonel Franz Royer to the Elector. High reliability and accurate description. Here it is explained why the battle on the Bavarian right wing was so unfortunate. Written by Royer after his exchange (treated in detail by Riezler, meeting reports 1901).

- Volume 2861 Page 257: Letter from Maximilian to the Emperor. August 11, 1645.

- Volume 2861, page 260: The Emperor's answer to Maximilian's letter.

- Austrian State Archives / War Archives, Old Field Files (AFA)

- 1645 8-15: Letter from Johann von Werth (probably to Piccolomini). Because of the neutrality of Nördlingen. Donauwörth, August 8, 1645

- 1645 8-15: Supplement to Werth's letter, without clear indication of the author.

- 1645 8-45½ : Letter from the Quartermaster General Reischenberg (probably) to Piccolomini, with a description of the battle.

Web links

- Depiction of the battle in the Theatrum Europaeum

- Local history of Alerheim with brief information about the battle at alerheim.de

- Archaeologists discover mass graves from the Thirty Years' War on portal: Spiegel.de

- Mass grave discovered near Alerheim , report at augsburger-allgemeine.de

- Napoleon "Précis des guerres du maréchal de Turenne", Paris 1869

Individual evidence

- ^ Abelinus, Johann Philipp and Merian, Matthias: Theatrum Europaeum, Volume V, p. 782. Retrieved on March 29, 2013 .

- ^ Johann Friedrich Weng: The battle near Nördlingen and the siege of this city in the months of August and September 1634 , p. 195

- ↑ Theatrum Europaeum, Volume V, p. 783 ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Abelinus, Johann Philipp and Merian, Matthias: Theatrum Europaeum, Volume V, p. 783. Retrieved on March 29, 2013 . Theatrum Europaeum, Volume V, p. 784.

- ↑ August Jassoy: Our Huguenot Ancestors and Others. A contribution to the tribal history of the Jassoy family , Knauer, Frankfurt / M., 1908, p. 227.

- ^ A b Johann Friedrich Weng: The battle of Nördlingen and the siege of this city in the months of August and September 1634 , page 196

- ^ Johann Friedrich Weng: The battle of Nördlingen and siege of this city in the months of August and September 1634 , page 197

- ^ Theatrum Europaeum, Volume V, p. 786

- ↑ a b Wilhelm Schreiber: Maximilian I, the Catholic, Elector of Bavaria and the 30 Years War , page 873

- ^ Anton Steichele: The Diocese of Augsburg , page 1171

- ↑ Abelinus, Johann Philipp and Merian, Matthias :: Theatrum Europaeum, Volume V, p. 786. Retrieved March 29, 2013 .

- ↑ Christoph von Rommel: History of Hessen , page 683-684.