History of the city of Freiberg

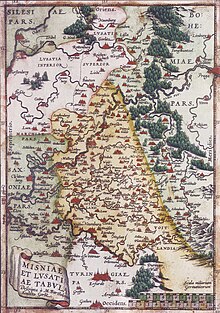

The history of the city of Freiberg is closely linked to mining . Established around 1162/70, Freiberg was the largest city in the Mark Meissen and its important trading location in the high Middle Ages . The Bergakademie , founded in 1765, is one of the oldest mining engineering universities in the world.

Beginnings

Until the middle of the 12th century, the region around present-day Freiberg was located in the primeval forest called Miriquidi , which covered large parts of present-day southern Saxony and stretched over the Ore Mountains to northern Bohemia . Between 1156 and 1162, Margrave Otto the Rich began clearing the forest and creating forest hoof villages . This also included Christian village with the parish church of St. Donati, consecrated in honor of St. Donatus of Arezzo , one of the patrons of the diocese of Meißen , and located near today's Donat Tower . When rich lead ores containing silver were discovered around 1168/70, the city of Freiberg was established within a few years. Already at the end of the 12th century it was about as big as the older Leipzig with 46.4 hectares. The ore deposit - later known as the Freiberg Central District - is the famous, approx. 35 × 40 km large vein deposit of precious and non-ferrous metals . According to a legend, after the discovery of the ore deposit, miners from Goslar moved to Christiansdorf and settled in the second settlement at this point named after their origin, the civitas saxonum , in German: Saxon town , and founded an independent parish church - the Jakobikirche . The establishment of this settlement attracted the customers that the " mountain was free " . The founding of the city in 1186, which is repeatedly mentioned in the literature, is based on several errors, rather the beginnings of the city must be set much earlier - shortly after 1168/70. In this context, the so-called Burglehnviertel was created around the parish church of Our Lady (later the cathedral) and the Nikolaiviertel around the Nikolaikirche , which was not a merchant church. Around 1170/80 the margravial manor was also built as a castle, which Margrave Otto the Rich of Meissen had built ( Freudenstein Castle since the 16th century ). As archaeological excavations and the dendrochronological determination of several wooden streets show, the planned and regularly laid out upper town around Obermarkt and Petrikirche had been under construction since the 1180s.

The Marienkirche was founded from 1180 to 1185 . Around 1220/40 ( dendrodatum 3rd tower storey 1224/25) the towers of the Nikolaikirche were built as the last remaining above ground of the second Romanesque stone Nikolaikirche, after the demolition of the first, probably around 1170, first stone church (hall) since the end of the 12th century was built. The oldest remains of the Petrikirche, however, date from the early 13th century.

The name "Freiberg" was first documented in 1201. City and mountain constitution, the "ius Freibergensis" , which was mentioned in the Kulmer Handfeste 1233, represented a unit and civil autonomy had a high level. In the 1220s, the council constitution in Freiberg was created, which is the earliest trades in a marchmeißnischen city. From 1227 the Romanesque town seal, the oldest of the Mark Meissen, was used.

The further development in the 13th century is characterized by constant growth after the commune was almost completely destroyed by a city fire around 1225. Shortly before the middle of the 13th century, the Franciscan and Dominican monasteries were founded and a Magdalenian monastery , the so-called virgin monastery , was set up on the already existing Jakobikirche, which is first attested in 1248. A city school was established in 1260 and converted into a Latin school in 1515. The high point of early urban development is marked by the codified Freiberg mining law from around 1300. In the 14th century there were gradually crises, which were mainly caused by the decline in silver production since the middle of the 14th century and in large-scale city fires in 1375 and 1386. In 1400 the first miners' union was named. The absolute low point followed in the second half of the 15th century, with the city again being largely destroyed by two city fires in 1471 and 1484. In the 15th century, Freiberg lost its leading economic position within Saxony to Leipzig due to the migration of capital . The establishment of a collegiate foundation at the Church of Our Dear Women in 1480 can be rated as a great success in times of greatest crisis. Since then, the designation “cathedral” has been common for the parish church.

Local historians consider Freiberg to be the mother of the Saxon mining towns , which has nothing to do with the real political situation. Rather, Freiberg was the first Wettin mountain town, numerous non- Wettin mountain towns, such as the mining town of Dippoldiswalde founded by the Burgraves of Dohna in the 12th century and later other mining towns in other areas of today's Saxony (Ore Mountains and Ore Mountains Foreland , Reichsland Pleißen ) emerged completely independently of Freiberg . In the high Middle Ages, the city was the economic center and at the same time the most populous city in the Margraviate of Meissen . The Freiberg mint was the main mint of the Wettins from the 13th century until it was moved to Dresden in 1556.

Early on, modern forms of production and trading were created in pits , smelters , long-distance trade and money business.

After Leipzig was divided in 1485, Freiberg and its ore mines owned both lines. At the time of the Reformation it became a prince's seat and thus a Saxon residence in 1505, where Heinrich the Pious ruled . His wife Katharina von Mecklenburg promoted the Protestant faith. During this time, after the last big city fire from 1484 to 1512, the cathedral with the tulip pulpit by Hans Witten around 1505, the canon court 1484/88, the late Gothic town hall from 1470 to 1474, the late Gothic Nikolaikirche around 1500 to 1520 as well as town houses in the style from late Gothic and Renaissance . From 1541 to 1694 ( August the Strong converted to Catholicism) the cathedral was the burial place of the Wettins.

In the 16th century silver mining flourished again, new mining facilities and smelting works were built. This was reflected in metal processing and handicrafts ( Hilliger's bell foundry ) and in science through the work of the doctor and mining scientist Ulrich Rülein von Calw . The first printing house is proven in 1550. Mining water systems of today's so-called Revierwasserlaufanstalt Freiberg , which were built around 1550 at the instigation of the miner Martin Planer , extend with ponds and artificial ditches further south to Sayda . The aboveground and underground systems with their ponds and ditches were mainly used to bridge the supply of process water , otherwise mining would have come to a standstill. It was also possible to advance more than 400 m in depths . Blasting with explosives in mining was invented in 1613 by Martin Weigel or Weigold in Freiberg and it was not until 1643 that it became more general in Saxony.

In Freiberg, witch hunts were carried out from 1542 to 1659 : five people got into witch trials .

17th century

In the Thirty Years' War the Electorate of Saxony was allied with the Swedes against the Emperor during the phase of the Swedish War (1630–1635) and an imperial army had occupied the city. After Johann Georg I, Elector of Saxony, made the Peace of Prague with the Emperor in 1635 , Saxony had switched to the Emperor's side and was repeatedly the target of attacks for the Swedes, in which the mining industry was and only was severely affected after 1700 regained its boom.

The Saxon cities were also targets of Swedish sieges . In the case of Freiberg, the sieges of 1639, 1642 and 1643 were successfully repulsed by Georg Hermann von Schweinitz . In the defense was also in 1577 in the style of Renaissance rebuilt Freudenstein Castle a part of the defenses of the town of Freiberg, by being temporarily used as a military base.

18th century

- In the Battle of Freiberg , the last battle of the Seven Years' War , Heinrich von Prussia , a brother of Frederick the Great , defeated the Austrians on October 29, 1762 .

- In 1765, the Bergakademie was founded as the second mining science university in the world (after that in Schemnitz / Banská Stiavnica in Slovakia).

- The Northern Wars , the Silesian War and the Seven Years War again caused considerable damage to the city and the mining industry. In 1724 and 1728 there were two more local city fires within the city.

- In 1790 the city theater was opened.

Modern excavations

In the second half of 2012, 127 burials were archaeologically documented on the site of the former “Green Cemetery” south of the cathedral and bones were recovered from 102 graves. Due to limited funds, 35 adult skeletons were selected for the anthropological research. The 30 children's skeletons were processed as part of a bachelor thesis ( University of Munich ). Based on burial customs, the graves could be dated to the early modern period, around the 17th and 18th centuries. The quality of the burial is testimony to the wealthy class of the population who were socially superior and buried their dead here. Of the 35 adults, one was adolescent, 10 fully grown, 17 advanced in age and 5 very old. 19 of those buried were female, 15 male. In the case of a skeleton, neither gender nor age could be determined. The exposure to dental caries in women was more than twice as high as in men. Presumably, upper class women consumed significantly more desserts than men. The frequency of hyperostosis frontalis interna , benign thickening of the skullcap in the area of the frontal bone towards the inside, was striking . This could possibly be related to obesity. There was a suspected case of syphilis and an extremely severe scoliosis . Infectious diseases were only detectable in low frequency. Likewise, severe degenerative changes in joints and vertebrae were found only in a few individuals, which indicated little physical stress.

19./20. Century to 1945

On June 2, 1839 the new pond broke and flooded the Münzbachtal . In the revolutionary years of 1848 and 1849 , Freibergs fought on the barricades in Dresden. Until 1856 Freiberg was the seat of the Electoral Saxon or Royal Saxon District Office Freiberg . In 1856 the city became the seat of the Freiberg judicial office and, after the judiciary and administration were separated in 1875, the Freiberg district administration .

In the 19th century, considerable parts of the city fortifications with their former five city gates were demolished. On March 14, 1860, the Freiberg Antiquities Association was founded , which presented its holdings from the antiquities collection and the library to the public with the opening of the Freiberg Museum on March 17, 1861. In 1862 the railway connection to Dresden , 1869 to Chemnitz, 1873 to Nossen and 1875 to Mulda . The connection to the German railway network and the construction of a very spacious train station favored accelerated industrial development. In 1886 the so-called Freiberg secret society trial took place against August Bebel and others. At the beginning of the 20th century, almost all ore mines had to cease operations. Since 1903, the Jews residing in Freiberg and those temporarily studying there held their services in the “Hornmühle” restaurant and later in the “Stadt Dresden” restaurant hall . Freiberg was the seat of the Amtshauptmannschaft Freiberg established in 1874 and left it in 1915; the city then remained district-free until 1946. On October 27, 1923, the actions of the Reichswehr in the context of the Reich execution claimed 26 lives.

On October 7, 1944, 24 American "flying fortresses" B-17 , which had loaded 60 tons of explosive bombs, were attacked by air on Freiberg and Wurzen . In Freiberg, the suburb of the station was particularly affected, but also Chemnitzer Strasse, Hainicher Strasse and Kleinwaltersdorf . 75 houses were destroyed or badly damaged, and 216 others were damaged moderately or slightly. 172 people died, including 133 women and children. 114 wounded were to be treated.

During the time of National Socialism there was a women's subcamp of the Flossenbürg concentration camp in Freiberg from August 31, 1944 to April 14, 1945. The 1,000 Jewish women, together with Polish forced laborers, had to work in the district office building for Arado Flugzeugwerke GmbH Potsdam-Babelsberg (camouflage name "Freia GmbH") produce armament parts.

1945 to the present

The population of Freiberg grew by leaps and bounds due to the inclusion of many bombed-out people from the surrounding cities and displaced persons. Freiberg was captured by the Red Army on May 7, 1945 , and the mayor at the time, Dr. Hartenstein (NSDAP), who held this office from 1924 to 1945, played a special role. He succeeded in protecting the city from unnecessary losses and secretly preparing for the city's surrender.

Freiberg belonged with all of Saxony to the Soviet occupation zone . Efforts by SDAG Wismut in the post-war period to find fissile material in the form of uranium ore in the Freiberg mining area were unsuccessful. In 1952 Freiberg was added to the Karl-Marx-Stadt district as part of an administrative reform in the GDR . Freiberg became the county seat of the Freiberg district . Large parts of the current campus of the TU were built in the 1950s and 1960s. In 1965 an inner-city bus service was set up again as public transport . The mining of zinc and lead continued until 1969 before it was stopped due to insufficient yield . Due to the massive expansion of the metallurgical industry in and around Freiberg to the center of non-ferrous metallurgy ( tin , zinc and lead in Freiberg, in the immediate vicinity precious metals in Halsbrücke and trace metals in Muldenhütten ) and because of the unsatisfactory solution to the problem of waste water and waste gas cleaning There was enormous damage to the environment in the near and far. In the south, southwest and west of the city, larger residential areas were built between 1964 and 1990. By 1970 the population exceeded 50,000. In 1990 Freiberg became the seat of the Saxon district of Freiberg , which in 1994 around the districts of Flöha and Brand-Erbisdorf and the community of Neuhausen / Erzgeb. from the district of Marienberg was expanded and in 2008 in the district of central Saxony . Since then Freiberg has been the district town of this district.

In February 2015, an explosives attack was carried out on a home for asylum seekers in Freiberg . The public prosecutor's office was investigating attempted manslaughter, but the investigation has now been discontinued, according to ARD .

In October 2015, around 400 asylum opponents and members of xenophobic groups tried to prevent more than 700 refugees from passing through Freiberg with sit-in blocks and attacked the convoy.

literature

- Hubert Ermisch : Document book of the city of Freiberg in Saxony. Volume -III. (= Codex diplomaticus Saxoniae regia II). Leipzig 1883-1891, pp. 12-14.

- Tom Graber: Document book of the Cistercian monastery Altzelle. First part 1162-1249. (= Codex diplomaticus Saxoniae II, 19). Hanover 2006.

- Andreas Möller : Theatrum Chronicum Freibergense. Description of the old, laudable mountain capital Freyberg in Meissen. Freybergk 1653.

- Gustav Eduard Benseler : History of Freiberg and its mining. 2 volumes. Freiberg 1843/1853.

- Richard Steche : Freiberg. In: Descriptive representation of the older architectural and art monuments of the Kingdom of Saxony. 3. Issue: Amtshauptmannschaft Freiberg . CC Meinhold, Dresden 1884, p. 8.

- Manfred Unger : Municipality and mining Freiberg in the Middle Ages. (= Treatises on commercial and social history 5). Weimar 1963.

- Walther Herrmann: The Freiberger Bürgerbuch 1486–1605. (= Sources and research on Saxon history 2). Dresden 1965.

- Heinrich Magirius : The Freiberg Cathedral. Research and preservation of monuments. Weimar 1972.

- Karlheinz Blaschke : Freiberg. German City Atlas, Delivery II, No. 2. Dortmund 1979.

- Günther Wartenberg : The effects of Luther on the Reformation movement in the Freiberg area and on the development of the Protestant church system under Duke Heinrich of Saxony. In: Hostels of Christendom 1981/82. Berlin 1982, pp. 93-117.

- Heinrich Douffet , Arndt Gühne: The development of the Freiberg city plan in the 12th and 13th centuries. In: Series of publications by the City and Mining Museum. 4: 15-40 (1983).

- Hanns-Heinz Kasper , Eberhard Wächtler (Hrsg.): History of the mountain town Freiberg. Weimar 1986.

- Otfried Wagenbreth , Eberhard Wächtler (ed.): The Freiberg mining industry. Technical monuments and history. Leipzig 1986.

- Uwe Richter: Archaeological investigations in Freiberg. New insights into the early history of the city. (= Series of publications by the Freiberg City and Mining Museum 12). Freiberg 1995.

- Uwe Schirmer : Freiberg silver mining in the late Middle Ages (1353–1485). In: New archive for Saxon history. 71 (2001), pp. 1-26.

- Yves Hoffmann, Uwe Richter (ed.): Monuments in Saxony. City of Freiberg. (= Monument topography of the Federal Republic of Germany). Articles, Volume I-III. Freiberg 2002-2004.

- André Thieme : On the early history of Altzelle and Freiberg. In: New archive for Saxon history. 74/75 (2004), pp. 383-390.

- Uwe Richter, Wolfgang Schwabenicky : The beginning of Freiberg mining, the boundary description of the Altzelle monastery and the development of the city of Freiberg. In: Rainer Aurig, Reinhardt Butz, Ingolf Gräßler, André Thieme (eds.): Castle - Street - Settlement - Dominion. Studies on the Middle Ages in Saxony and Central Germany. Festschrift for Gerhard Billig for his 80th birthday. Beucha 2007, pp. 311-330.

- Wolfgang Schwabenicky: The medieval silver mining in the Erzgebirge foothills and in the western Erzgebirge. Chemnitz 2009.

- Yves Hoffmann, Uwe Richter: Development and prosperity of the city of Freiberg. The structural development of the mountain town from the 12th to the end of the 17th century. Halle 2012, ISBN 978-3-89812-930-5 .

Individual evidence

- ^ Herbert Pforr: Freiberg silver and Saxony's shine. Lively history and sights of the mountain capital Freiberg. 1st edition. Sachsenbuch Verlagsgesellschaft Leipzig 2001, ISBN 3-89664-042-9 .

- ↑ Manfred Wilde: The sorcery and witch trials in Saxony. Böhlau, Cologne / Weimar / Vienna 2003, ISBN 3-412-10602-X , p. 499f.

- ^ Project Green Cemetery at Freiberg Cathedral. In: anthropologie-jungklaus.de. Retrieved June 4, 2017 .

- ^ Bettina Jungklaus , Katharina V. Krippner: The "Green Cemetery" of Freiberg (district central Saxony). Results of the anthropological studies . In: State Office for Archeology, Free State of Saxony (Ed.): Excavations in Saxony . tape 5 , 2016, ISSN 0138-4546 , p. 415-430 .

- ^ Karlheinz Blaschke , Uwe Ulrich Jäschke : Kursächsischer Ämteratlas. Leipzig 2009, ISBN 978-3-937386-14-0 ; P. 72 f.

- ^ The Amtshauptmannschaft Freiberg in the municipality register 1900

- ^ The war children generation in Freiberg 1944/45 . Official Journal of the University City of Freiberg, No. 18, 2010. Report on a special exhibition (same name) in the Freiberg City Museum, 2010

- ^ Roger A. Freeman: Mighty Eighth War Diary . JANES's. London, New York, Sydney. 1981. ISBN 0-7106-0038-0 . P. 361

- ↑ Freiberg satellite camp. Website of the Flossenbürg Concentration Camp Memorial. Retrieved July 6, 2016.

- ↑ There could have been deaths: The firecrackers attack on the asylum seekers' home was an explosives attack. In: Focus Online . June 19, 2015, accessed March 11, 2016 .

- ↑ Thomas Reutter (director); Südwestrundfunk (Production): Terror from the Right - The New Threat. Report & documentation. Series: The story in the first . (No longer available online.) In: daserste.de. Archived from the original on March 10, 2016 ; accessed on March 11, 2016 (first broadcast on ARD on March 7, 2016 - with video stream , length: 44:02 minutes; about the bomb attack in Freiberg from approx. 08:03 minute).

- ↑ Police protect refugees in Freiberg with large numbers. In: tagesspiegel.de . October 26, 2015, accessed October 27, 2015 .

- ↑ State Directorate: Riots in Freiberg without an example in: Freie Presse of October 26, 2015