Bloody Christmas (1963)

A long, civil war-like dispute between Greek and Turkish Cypriots between the end of 1963 and the summer of 1964 was described as a bloody Christmas first by the Turkish Cypriot population, and about three decades later also by international research literature. The term was charged with propaganda by the Turkish side and used in school lessons, but also in specialist publications. Until a few years ago it dominated the culture of remembrance of the Turkish part of the island's population. The term appeared in national German daily newspapers in 1974 at the latest.

Prehistory and classification

The British colony of Cyprus gained independence on August 16, 1960 on the basis of the Zurich Agreement between Great Britain, Greece and Turkey, which was signed in February 1959. The Greek- and Turkish-speaking nationals of the new state should have equal rights. Archbishop Makarios III became the first president . († 1977) elected, who belonged to the Greek-speaking majority. Both the USA and the Soviet Union interfered in the conflict against the backdrop of the Cold War , but above all the old conflict between Greece and Turkey escalated. In this conflict since the 1920s, millions of Greeks from western Turkey, but also hundreds of thousands of Turks from Greece, had been driven out.

In order to avoid conflicts in Cyprus, the constitution granted the Turkish minority a share of 30% of the parliamentary seats, as well as a corresponding share in the administration, plus 40% in the army and the police. In addition, separate administrations should be set up in the five largest municipalities where Turks and Greeks lived; Separate jurisdiction was also granted to the two language groups. In particular, the Vice-President, who should always be appointed by the Turkish Cypriot side, was granted extensive veto rights.

In 1963 Makarios wanted to push through a new constitution in which the veto rights of the president and the vice-president in matters of defense, foreign relations and security legislation should be eliminated. In addition, the separate judiciary and city administrations should be abolished. The reason was the finding that the Turkish minority was in practice not in a position to fill the positions allocated to them according to the 7: 3 key. On November 30, 1963, Makarios submitted a 13-point memorandum to amend the constitution. The Turkish side suspected Makarios of wanting to join the island to Greece. Although Makarios' call for a constitutional amendment is seen as the trigger for the bloody Christmas and thus the prelude to the Cyprus conflict, recent studies show that both Turkish and Greek groups had previously organized arms deliveries. While the Greeks hoped to achieve their goal of joining Greece ( Enosis ), the Turks hoped for the division of the island ( Taksim ). But many Turkish Cypriots were against the division. While the Greeks later claimed that the Turks left the government voluntarily, the Turks claimed that they were forced to. But Turks, who remained loyal to the government as a whole, gave the opposite impression, as they stayed away from office. In many cases, however, this was done out of fear of attack or out of concern that their loyalty might be viewed as betrayal of the Turkish cause. At the beginning of 1964 the island government was practically exclusively in Greek hands. At the latest with the fact that the Turkish head of the gendarmerie and the deputy chief of police were brought before a Turkish special court on January 7, 1964 because they had refused to set up their own police force on the instructions of the Turkish-Cypriot leadership, every Turkish person had to be clear that loyalty to the entire government was considered high treason. In Famagusta, however, Turkish-speaking civil servants continued to come to work.

Since Makarios' constitutional amendment, there had been tensions: on December 21, 1963, the Armenian houses in the capital were occupied - they had voted for Greece with a large majority in the referendum - and on January 19, 1964, the remaining houses in the neighborhood were looted. After threats, 231 Armenian and 169 Greek families fled. On the same day there was a massacre of Turkish Cypriot civilians by Greek Cypriot police forces, which was followed by more, what the Turkish side called a "Bloody Christmas". On December 21 and 22, 1963, 133 Turkish Cypriots were killed by Greek Cypriots.

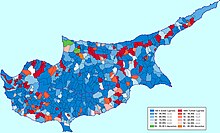

These mutual attacks formed the prelude to fighting in which a total of around 1,000 Turkish and at least 200 Greek Cypriots died. Militant activist Nikos Sampson later boasted of murdering 200 Turkish women and children. Between December 1963 and the end of the conflict in the summer of 1964 alone, 364 Turkish and 174 Greek Cypriots lost their lives. 18,667 Turkish Cypriots from 103 villages left their homes, which marked the beginning of the ethnic division of the island into a Turkish north (apart from the Karpas peninsula) and a Greek south.

course

In the early morning of December 21, 1963, at a time when there were rumors that Greek Cypriot militias were holding exercises to set up blockades in Nicosia, a vehicle was stopped by irregular Greek Cypriot units. The militiamen asked the inmates to show their identification papers. In this tense atmosphere, Turkish Cypriot militiamen appeared in the streets. At around 3:20 am, the first gunfire was reported. By the evening two men of Turkish descent were dead and eight other men of both Greek and Turkish descent were injured. The first two victims were the Turkish Cypriots Zeki Halil and Cemaliye Emirali. After driving through the Greek neighborhoods of Nicosia with others , a group of armed Greek civilians stopped two vehicles as they arrived in the Turkish neighborhood and forced the ten occupants to get out. When the Greek Cypriot police arrived, the Greek civilians stepped aside and the police fired into the crowd of Turkish Cypriots.

Calls by the President and Vice-President to keep calm had no effect; There were also exchanges of fire in other parts of the capital. The next day there was fighting in Larnaka , but it remained quiet until the next day. Only after an attack on Greek Cypriot families in the Omorphita district of Nicosia did the fighting flare up again, now also in Famagusta and Kyrenia .

As a result, the Turkish Cypriot leadership, supported by the government in Ankara , took a tough course. The extremists in both camps continued to fuel the conflict, so that the clashes took on civil war-like proportions. In addition to Nikos Sampson, who is considered a hardliner, and his colleagues, there were also terrorist groups on the Greek side, some of which had emerged from EOKA . To date, the Makarios government is suspected by the Turkish side of wanting to wipe out the group of Turkish Cypriots.

As late as December 23, the British government, as one of the three guaranteeing powers, considered the matter to be an internal matter. However, on December 24, the Cypriot Foreign Minister was invited to the Commonwealth Office , and the Turkish Foreign Minister held meetings with the American and Soviet ambassadors. The three guarantee powers called on the islanders to stop fighting, but at Christmas, after three Turkish fighter planes had crossed Nicosia at low altitude, fighting broke out on the strategically important Kyrenia Strait, in particular around the village of Gunyeli . In a special session, London made preparations to protect the 15,000 British people on the island.

The Turkish public was in favor of intervention, and general mobilization seemed imminent. However, the government preferred joint intervention by the guarantee powers, but was prepared to act alone if this plan should fail. The Greek government was less under public pressure. Athens also preferred joint action, but was concerned about Turkish warships that had been sighted off the coast of Cyprus. On December 25, the government of Cyprus was informed that the three guaranteeing powers, led by Great Britain, would restore order if the government asked them to do so. Makarios asked for a time to think about it, but agreed in principle on the 26th.

In the meantime, the Turkish troops had left their camp on December 25th. Some of them helped the island Turks to fortify their positions. Others had also taken part in direct battles against Greek islands near Ortaköy north of Nicosia. Greek contingents had also taken part in the fighting, but after Makarios agreed they had withdrawn to their camps. Since Greece refused to take part in the joint action without Turkish participation, some older Turkish officers had to serve in order not to endanger the company. In addition, the Turkish troops refused to submit to the British command without an order from Ankara. With that the British troops were practically alone.

The fear of attacks initially led Turkish Cypriots to leave the mixed-populated areas. This exodus was used, promoted and instrumentalized for propaganda by the Turkish side. As a result, the Greek Cypriot leadership blocked the access to Turkish Cypriot enclaves , so that the residents were cut off from the supply of water, electricity and food.

On December 27, the Joint Truce Force of the Guarantor Powers took up position in Nicosia. At the same time, doctors began treating several hundred injured Turkish Cypriots. General Peter Young initially seemed to succeed in ending the fighting, which only flared up sporadically. The governments in Ankara and Athens were also optimistic.

But the British Air Force reported that Turkish warships were only 15 to 20 miles off the coast of Cyprus on their way to İskenderun , as it later turned out. The Greek Cypriots took this question to the UN Security Council on the morning of December 28th . After the Turkish fleet withdrew - although Ankara, as a guarantor power, felt entitled to approach Cyprus - London hoped to prevent the Cypriot Foreign Minister, Spyros Kyprianou , from calling the Security Council. In the end, he did not see any decisions. Athens, however, put its fleet on alert. A debate began in London about using a UN force on the island to keep the conflict between Athens and Ankara out of the island conflict.

Meanwhile, Ankara assured that it was only pressing ahead with war preparations in İskenderun to reassure the Turkish Cypriot public. London, however, feared that Ankara was preparing a unilateral intervention. On December 28th, Duncan Sandys, British Commonwealth Secretary , arrived on the island. He managed to convince the official representatives and the leaders of the fighting units that British troops should guard a line of demarcation . The dead were to be handed over to their respective compatriots, prisoners to be exchanged. In addition, the telephone connection between Nicosia and Kyrenia should be restored. Now, however, Makarios submitted the plan, which had already been mentioned on December 23rd, to sever ties with the guaranteeing powers and to regard only Great Britain as the guaranteeing power. Ankara refused, while Athens agreed. Since the Turkish troops had still not returned to their barracks, the Greeks threatened to no longer recognize the British leadership. At this point in time Nicosia was practically divided: the Turkish group lived in the north and the Greek group in the south.

Foreign journalists first appeared on December 28 in Nicosia , where they reported massacres of 200 to 300 people. Not only were Greeks at risk from Turks and vice versa, but, as corresponding complaints showed, Turkish Cypriots were also at risk from members of their own language group who stood by the government. On January 14, 1964, reported the Daily Telegraph , that the Turkish Cypriots of Agios Vasilios were massacred on December 26, 1963, their mass grave in the presence of members of the Red Cross had been dug. The Greek Cypriot side claimed that the bodies, which were also found in other places, had been deceased in hospitals that the Turks wanted to show as victims. On the same day, the Italian Il Giorno realized that a mass exodus to the north had begun. The Turkish Cypriots viewed Turkey all the more as their protective power.

On February 17, the Washington Post wrote : "Greek Cypriot fanatics appear bent on a policy of genocide." When Greek Cypriot police attacked Agios Sozomenos on February 6, they were not stopped by British troops either. On February 13th, the Turkish quarters in Limassol were attacked by tanks.

Ethnic division

Around 20,000 Turkish Cypriots are said to have given up their homes. The actions of both sides led to the division of the island being initiated. Rauf Denktaş , who proclaimed the Turkish state of Cyprus in 1975, of which he was president from 1976 to 2005, justified his refusal to resolve the Cyprus conflict by returning to the status quo ante , including the traumatization of his compatriots by the bloody Christmas of 1963. A total of 270 mosques, shrines and other places of worship were desecrated.

Concept history

The massacre of members of the Turkish minority in Cyprus was initially given a variety of names, as is usually the case in such cases. On the Turkish side, the name Kanlı Noel became popular in the 1970s, and it appeared in a Turkish publication as early as 1964. This term was initially taken up by the Turkish literature, in 1984 the Turkish Cypriot Human Rights Committee , the human rights committee of the Turkish Cypriots, referred to the processes with this term.

For a long time the term appeared exclusively in Turkish publications, but appeared in German newspapers at the latest in 1974, when the Cyprus conflict came back into the focus of the global public. But during the 1990s, as the conflict between Greece and Turkey eased, it also appeared in Anglo-Saxon publications. From there he penetrated historical journals. The Bulgarian Historical Review (2005, p. 93) quoted from a Turkish publication from 1989 which was devoted to the event. The term had previously appeared in comprehensive historical works, occasionally in quotation marks. At the latest with specialist publications from the USA, the term should also have been established in scientific literature, without the original propaganda function being displaced.

With the opening of the inner Cypriot borders, a process of reappraisal began in which the widely diverging use of terms, which mostly served to assign blame, was analyzed. Knowledge of the nationalistic creation of terms and their use in the media, school books and museums could contribute to the creation and maintenance of an enemy image, as well as the exploration of motifs of remembrance and oblivion towards reconciliation.

Since 1974 the Greeks have been systematically remembering the "Turkish occupied Cyprus", the Turks acted similarly and founded a Barbarlık Müzesi , a "museum of barbarism". Like the Greeks, they wanted to remember the massacres forever (unutmayacağız) , especially the bloody Christmas. Turkish school books such as Kıbrıs Türk Mücadele Tarihi focused on the suffering inflicted on the Turks in Cyprus, much as the Greeks did. The mutual crimes were projected back into the past indefinitely and one-sided accusations and clichés were the rule, especially in school books.

In 2003, however, there was a revision of the Turkish-language textbooks, which gave the Greeks more positive space in the history of Cyprus and less used the historically verifiable motifs for propaganda purposes. To reflect the subjective perception of suffering and the decreasing tendency to attribute the deeds exclusively to the Greek Cypriots, the term "bloody Christmas" is now placed in quotation marks again.

On the Greek side there was a revision of the school books from 1997. Source-based comparisons were encouraged there, and the long peaceful phases were at least mentioned, even if stereotypes of the brutal and uneducated Turks continued to be cultivated. From 2004 onwards, there was a wider debate about the goals of such works. Since then, overarching groups have endeavored to achieve critical distance, the establishment of historical-critical methodology and acceptance of the suffering of “others” as well as the presentation of available sources.

The term “Bloody Christmas” has not yet established itself among the Greek Cypriots, in contrast to the Turkish Cypriots. As recently as 2012, Halil Ibrahim Salih remarked in contrast to the Greeks that "the Turkish Cypriots call it 'the bloody Christmas massacre'".

Web links

- Committee on Missing Persons in Cyprus (CMP) ( Memento from October 23, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) of the UN

Remarks

- ↑ This and the following after: Bloody unrest in Cyprus. England mediates between the Turks and Greeks. In: Die Zeit, January 3, 1964.

- ↑ James Ker-Lindsay: Britain and the Cyprus Crisis 1963-1964. P. 39 f.

- ↑ Alexander-Michael Hadjilyra: The Armenians of Cyprus , o.O. 2009, p. 16.

- ^ British Turks asked to remember victims of Bloody Christmas 1963. In: North Cyprus Free Press, December 14, 2010.

- ↑ Eternal trouble spot. In: Die Zeit, Dossier, 2002.

- ^ Pierre Oberlinga: The Road to Bellapais. The Turkish Cypriot exodus to northern Cyprus , New York 1982, p. 120.

- ↑ M. Abdulhalûk Çay: Kıbrıs'ta kanlı Noel, 1963 . Türk Kültürünü Araştırma Enstitüsü, 1989.

- ↑ This and the following from: James Ker-Lindsay: Britain and the Cyprus Crisis 1963–1964. P. 24 ff.

- ↑ Aydın Olgun: Kıbrıs Gerçeği (1931–1990). Demircioğlu Matbaacılıkm, Ankara 1991, p. 25.

- ^ Memoirs of Prof. Ata Atun .

- ↑ Harry Scott Gibbons: The Genocide Files. Charles Bravos, London 1969, pp. 2-5.

- ↑ This thesis is supported by Ali Özkan: Enosis, Kanlı Noel olayı ve birleşmiş milletlerde Kibris sorununda Türkiye'ye arnavutluk desteği / Enosis, Bloody Christmas and Albanian Support to Turkey on Cyprus Question in the United Nations. In: The Journal of Academic Social Science Studies 6.2 (2013) 765–796.

- ↑ This and the following from Michael Stephen's account : Why is Cyprus devided? Report to the British Parliament or the Select Committee on Foreign Affairs of September 30, 2004.

- ↑ According to Adel Safty: The Cyprus Question. Diplomacy and International Law , iUniverse, Bloomington 2011, p. 249.

- ^ Pierre Oberling, The road to Bellapais: The Turkish Cypriot exodus to northern Cyprus, 1982, ( ISBN 0-88033-000-7 )

- ↑ Michael Stephen: Why is Cyprus devided? , Report to the British Parliament or the Select Committee on Foreign Affairs of September 30, 2004.

- ↑ Cevat Gürsoy: Kıbrıs ve Türkler , Ayyıldız Matbaası, Ankara 1964.

- ↑ Annales de la Faculté de droit d'Istanbul, 1981, p. 499.

- ↑ Lothar Ruehl: Is the southeast pillar bursting? Two allies of the Americans have wavered , in Die Zeit, 23 August 1974.

- ^ Vamik Djemal Volkan, Norman Itzkowitz: Turks and Greeks. Neighbors in Conflict , Huntingdon 1994, p. 140.

- ^ Nicole and Hugh Pope: Turkey Unveiled. A History of Modern Turkey. In: Overlook Press, Woodstock, NY 2000, p. 103.

- ↑ Baskın Oran, Atay Akdevelioğlu, Mustafa Akşin: Turkish Foreign Policy, 1919–2006. Facts and Analyzes with Documents. University of Utah Press, 2010, p. 412. The same applies to Umut Uzer: Identity and Turkish Foreign Policy. The Kemalist Influence in Cyprus and the Caucasus. Tauris, 2010, p. 127, or for Zvi Bekerman, Michalinos Zembylas: Teaching Contested Narratives. Identity, Memory and Reconciliation in Peace Education and Beyond. Cambridge University Press 2013, p. 13 (there also in the index), or Pal Ahluwalia, Stephen Atkinson, Peter Bishop, Pam Christie, Robert Hattam, Julie Matthews (eds.): Reconciliation and Pedagogy. Routledge, New York 2012, p. 55.

- ↑ Hakan Karahassan, Michalinos Zembylas: The politics of memory and forgetting in history textbooks: Towards a pedagogy of reconciliation and peace in divided Cyprus. In: Alistair Ross (Ed.): Citizenship Education. Europe and the World. London 2006, pp. 701-712.

- ^ Halil Ibrahim Salih: Reshaping of Cyprus. A two-state solution. 2012, p. 144.