Cali cartel

The Cali Cartel ( Spanish Cartel de Cali ) was an amalgamation of various Colombian cocaine producers and smugglers in the city of Cali . Founded by Gilberto Rodríguez Orejuela , his brother Miguel, and José Santacruz Londoño in the 1970s, it controlled 80 percent of Colombian cocaine exports to the United States at the height of its power.

The top management of the cartel was arrested in the mid-1990s and has been serving long prison sentences ever since. Observers assume that the Cali cartel has also broken up into several small and independently operating groups. The best known of these smaller groups is the extremely violent Norte del Valle cartel from the northern Cauca Valley .

founding

The Orejuela brothers and Londoño came from higher social classes as leaders of other contemporary organizations such as the rival Medellín cartel . Gilberto Rodriguez Orejuela was a pharmacist, his brother Miguel Angel was active in the real estate and construction industry and was responsible for the rise of the América de Cali football club . José “Chepe” Santacruz Londoño even had a degree as an economist. Orejuela ran a discount - pharmacy chain and shifted its activities to the processing of coca paste from the Andes, which in Leticia is rolled over. The social background earned the syndicate the group name "Gentlemen from Cali". The Cali cartel was originally formed from a ring of kidnappers, the “Los Chemas”, led by Luis Fernando Tamayo Garcia. "Los Chemas" were involved in numerous kidnappings, including a. by two Swiss citizens, the diplomat Herman Buff and the student Werner José Straessle. The $ 700,000 ransom from this action likely formed the capital for their international drug trafficking activities .

The newly formed group initially began smuggling marijuana , similar to the Medellín cartel . Due to the higher profit margin and the lower use of materials, the decision was made to export cocaine. In the early 1970s, Hélmer "Pacho" Herrera was sent to New York to explore the local market and look for larger sales opportunities. This came at a time when the DEA viewed cocaine as a less critical drug as opposed to heroin , which was much less addictive, and identified no link to any violent drug-procurement crime. While Gilberto and Miguel Rodriguez found outlets in New York, Houston and Los Angeles, José Santacruz Londoño opened up sales channels in San Francisco, Las Vegas and Chicago.

organization

The fact that cocaine was not initially the focus of the American DEA search allowed the Cali cartel to develop further in New York. The Cali cartel is divided into many smaller cells that operate independently of one another and report to a "Celeño" or manager who then reports to another level of management in the Cali cartel. The independent cell structure distinguishes the Cali cartel strongly from the dominant Medellín cartel. The Cali cartel acts as an umbrella group of independent criminal groups and cells, in contrast to the strictly hierarchical management function of Pablo Escobar from the Medellín cartel. The Cali cartel uses the methods of modern corporate management, starting with market studies up to an optimized supply chain of the flow of goods from Colombia to the USA.

While the Medellín cartel mostly cooperated with the army, in Cali it was the police that worked for the drug traffickers. The Cali cartel has been used since the mid-1970s. It expanded over the years and had around 2500 to 6000 members at its wedding. In contrast to the Medellín cartel, the Cali cartel was organized vertically and based on joint cooperation.

It is believed that each cell reported to a larger group and that this passed on to the management level. The following groups were named by the former accountant of the Cali cartel, Guillermo Pallomari:

- Drug trafficking: control over processing laboratories, shipping methods and routes

- Military: Control over personal safety, punishment and discipline related to bribery of the military and senior police officers

- Politics: Bribery of members of Congress, officials and politicians

- Finance: Control of money laundering , core business and cooperation with legal business activities

- Legal Department: Control over defense of arrested members, purchase from lobbyists and overseas representatives

Compared to Pablo Escobar's Medellín cartel, the Cali cartel was less noticeable. Profits from drug smuggling were reinvested in legal businesses and so washed away. After the competition between the two cartels escalated at the beginning of the 1990s and Escobar in particular became increasingly violent, the Cali cartel supported the paramilitary Los Pepes . This organization, which described itself as the protection force of the victims of Escobar, actually consisted of drug traffickers like Diego "Don Berna" Murillo-Bejarano and paramilitaries like Vincente Castaño and Carlos Castaño . At the same time, the Cali cartel specifically informed the police and the US anti-drug agency DEA about Escobar's actions.

After Pablo Escobar was shot dead in December 1993 and the Medellín cartel split up, competition from Cali quickly took over the vacated market. When the demand in the USA reached the saturation limit, the focus was increasingly on exporting to Europe and Asia.

In contrast to the Medellín cartel, the Cali cartel did not try to enforce its interests through direct confrontation with the state, but through infiltration and corruption. They also invested in the election campaign for President Ernesto Samper . This scandal came to light through the publication of the so-called “Narco cassettes”. Samper was now forced to crack down on the Cali cartel to prove his independence. The Cali cartel was described by DEA commander Thomas Constantine as follows:

"The Cali Cartel is the biggest, most powerful crime syndicate we've ever known."

"The Cali Cartel is the largest and most powerful criminal syndicate we have ever met."

activities

Drug trafficking

The Cali cartel, which began in the marijuana trade, quickly switched to the cocaine business because of its ease of transportation and a much larger profit margin. The cartel became famous for its innovations in the cocaine business by moving cocaine refining from Colombia to Peru and Bolivia . As a pioneer, the Cali cartel also created smuggling routes for larger transports through Panama for the first time . The supply of opium was diversified and a well-known Japanese chemist was hired to optimize the refinery methods for the Colombian conditions. According to Thomas Constantine's testimony to the US Congress, the Cali Cartel became the dominant organization in South America because of its access to the opium poppy growing areas in Colombia. The debate about the proportion of the involvement of the Cali cartel in the international heroin trade has not been fully resolved. It is believed that the leadership of the Cali cartel is not directly involved in the heroin trade, but associated partners such as Ivan Urdinola-Grajales, who has been associated with various heroin distribution centers. During the heyday of the Cali cartel, 70 percent of the world cocaine market was dominated and sales were driven forward, especially in Europe . In Europe, the Cali cartel even had a market share of 90 percent. In the mid-1990s, the Cali cartel was a multi-billion dollar multinational.

Finances

Money laundering of payments received directly from drug trafficking was carried out by investing in funds, which in turn came from legal transactions and were intended to cover larger payment flows. In 1996, sales are said to have been $ 7 billion. As the incoming money increased, the need for smarter alternatives to money laundering increased. Gilberto Rodriguez, as chairman of the “ Banco de Trabajadores ” (German: “Bank of the Workers”), which was also abused by the Medellín cartel for money laundering, used his position to enable business partners and members to overdraw their accounts and loans without repayment.

Gilberto established business relationships with First InterAmericas Bank in Panamá , which did most of its legal business. According to Gilberto Rodriguez, this was done in accordance with Panamá law. However, this did not save him from prosecution by US authorities. Gilberto later founded the "Grupo Radial Colombiano", a network of more than 30 radio stations and a drugstore chain called Drogas la Rebaja, which had 400 branches in 28 cities with 4,200 employees and generated around 216 million US dollars annually.

bribery

In contrast to the Medellín cartel, which had declared total war on the Colombian state, the Cali cartel came to terms with the authorities through bribery and favoritism. Gilberto is credited with the sentence: "We don't kill judges, we buy them". Miguel Orejuela had up to 2,800 people on his payroll, from politicians to taxi drivers. The rise of the cartel is also attributed to its good relations with the Colombian oligarchy . The biggest publicly known bribery scandal came from the election campaign of Ernesto Samper , who received six million US dollars from the Cali cartel for his election campaign. In 1995, Sampers campaign manager Santiago Medina and three ministers had to be fired because they had been shown to have received money from the Cali cartel. Because of the Cali cartel's extensive links with Colombian politics, prosecutor Alfonso Valdivieso claimed that "the corruption of the Cali cartel is worse than the terrorism of the Medellín cartel".

Disciplinary violence

Political violence was largely rejected by the Cali cartel, as the mere threat of violence often met their demands. The organization was structured in such a way that only people with families in Colombia were active in the US branches, so that the entire family was always within the disciplinary reach of the cartel. Threats to family members were used as leverage against testifying to the police or refusing to pay for goods received. Executions were often used on mistakes made by members, with new members being more likely to die for mistakes than senior members of the government.

Murders of members of marginalized social groups

Manuel Castells reports that the Cali cartel is responsible for hundreds or even thousands of victims of "cleansing operations" against the so-called " desechables " (German: "throwaway people"). In Colombia, prostitutes, street children, thieves, homosexuals, homeless people, tramps and vagrants are called “ desechables ”. Together with upper class groups and the police, death squads such as B. " grupos de limpieza social " (German: "Groups for social cleansing") was founded, which carried out such murders under the macabre motto " Cali limpia, Cali linda " (German: "Clean Cali, beautiful Cali"). Colonel Oscar Pelaez was instrumental in these "purges" and rose in the special group of the Dijin. The corpses were mostly thrown into the Río Cauca , which is popularly known as the "river of death". The administration of Marsella in the Risaralda department downstream from Cali lamented the ruinous high costs of the recovery of the water corpses and the autopsies to be carried out. The Medellín Cartel operated in its "purges" often in the countryside, while the Cali Cartel operated in the city.

Retaliation

In the early 1980s and 1990s, left-wing guerrillas fought the drug cartels. In 1981, members of the Movimiento 19 de Abril (M-19) kidnapped Marta Nieves Ochoa, the sister of the Ochoa brothers from the Medellín cartel. The M-19 requested a $ 15 million ransom but was turned away. In response to the kidnappings, the Medellín and Cali cartels founded the group “ Muerte a Secuestradores ” (German: “Death to the Kidnappers”) (MAS), with the drug traffickers providing financial resources, rewards, logistics, personnel, infrastructure and equipment . Leaflets about the founding of the MAS were dropped over a large football stadium. In retaliation, MAS commandos began capturing, torturing, and killing M-19 members. Marta Nieves Ochoa was released after three days. However, the MAS group continued to operate and is credited with hundreds of murders. In 1992, the FARC , a left-wing guerrilla movement, kidnapped Cristina Santa Cruz, the daughter of leader José Santacruz Londoño, and demanded a $ 10 million ransom for her release. In response, the Cali cartel kidnapped 20 or more members of the Colombian Communist Party, the Patriotic Union, the labor union and the sister of Pablo Catatumbo, a representative of the Simón Bolívar Guerrilla Coordinating Board. After talks, Cristina and Catatumbo's sister were released, but it is uncertain what happened to the other hostages.

In the terror war of the Medellín cartel against the Colombian government, Hélmer Herrera was supposed to be murdered during a major sporting event. The killer killed 19 people with the volleys of his submachine gun, but missed Herrera. In return, the Cali cartel had Pablo Escobar's cousin Gustavo Gaviria kidnapped and murdered. Herrera became the founder of Los Pepes , which, with the approval of the authorities, set out to pursue and kill Pablo Escobar .

Counterintelligence

The Cali Cartel's counter-espionage success baffled the DEA and the Colombian authorities. In 1995, a raid on the cartel's administrative offices led to the discovery that all telephone calls to and from Bogotá , including the US Embassy and the Department of Defense, were recorded. Londoño used state-of-the-art Israeli telecommunications technology specially developed for him to make tap-free phone calls with his partners in the USA. The Londoños laptop, which was later confiscated, contained encrypted files that even IT experts could not decipher. There were also around 5,000 taxi drivers on the Cali Cartel's payroll reporting the movements of suspects and newcomers. In 1991, Time magazine reported on an operation by the DEA and the US Customs Service in Miami , which the Cali Cartel was closely monitoring.

Relationship with the Medellín Cartel

First InterAmericas Bank

Jorge Ochoa, a senior financier of the Medellín cartel , and Gilberto Rodriguez were childhood friends and later jointly ran the Panamanian First InterAmericas Bank. This bank was later exposed by US authorities as a money laundering organ for the Medellín and Cali cartel. Only through massive political pressure on the ruler Manuel Noriega were these activities ended.

MAS Muerte a Secuestradores

After the abduction of Marta Nieves Ochoa, the two cartels worked together as the MAS. A second cooperation between the Medellín and Cali cartels emerged later. Both organizations divided the sales market in the USA between themselves: the Cali cartel was active in New York City and the Medellín cartel in South Florida and Miami . Both organizations were active in Los Angeles . Through the cooperation at MAS, both cartels agreed on price stabilization, production and shipping in the cocaine market. The strategic alliance through the MAS broke up between 1983 and 1984 when competition between the two increased sharply. Because the cartels had already created infrastructure, transport routes, transport methods and bribery in their sales area, it was easier for other syndicates to take over this organization than to develop new ones. In 1986 Jorge Ochoa was arrested by the police and the Medellín cartel suspected treason by the Cali cartel. In 1987 the MAS ceased to exist and an open declaration of war broke out between the two cartels when Rodriguez Gacha of the Medellín cartel tried to gain a foothold in New York.

Los Pepes

Later, when Pablo Escobar's terror against the Colombian government escalated, the state struck back against the Medellín cartel. The Medellin Cartel weakened with increasing pressure and fighting, while the Cali Cartel grew in strength and power. The Cali cartel founded the Los Pepes movement ( Spanish Perseguidos por Pablo Escobar , Pursued by Pablo Escobar) as a militant countermeasure against the terror from Medellín. The aim of the "Los Pepes" was the liquidation of Pablo Escobar and the smashing of the Medellín cartel, whose declaration of war seriously disrupted the cocaine business. The "Los Pepes" worked together with the Bloque de Busqueda police unit (German: wanted block ) and helped track down and locate Escobar. In return, "Los Pepes" were supported by the US counter-terrorism unit Delta Force . Over 60 people were murdered by "Los Pepes" because they were suspected of cooperating with the Medellín cartel. In 1993 Pablo Escobar was killed in a car chase and the Medellín cartel dissolved. The death of Pablo Escobar brought the Cali cartel sole control of the Colombian drug trade. The Cali cartel also took over the transport to Miami.

Prosecution

Confiscations

Although the Cali cartel initially worked with the police and government during the drug wars against the Medellin cartel, they were often the victims of seizures. In 1991, 67 tons of cocaine were seized, 75 percent of which belonged to the Cali cartel. In total, US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) spent 91,855 case hours and 13 years of investigative work against the Cali cartel, with only 51 tons of cocaine and just $ 13 million in assets seized. In 1991, Operation Cornerstone confiscated twelve tons of cocaine in cast concrete in the seaport of Miami. In 1992, six tons of cocaine were found in a cargo of broccoli, which led to seven arrests, and similar quantities were seized in this context in Panamá . In 1993, Raúl Marti, a Miami cell survivor, was arrested with large quantities of cocaine. The Cali cartel then had to relocate the transport routes from Florida to Mexico after three shiploads with a total of 13 tons of cocaine were seized in 1993. Even in the port of Hamburg, large quantities of cocaine have been discovered in ocean-going vessels that were being shipped to Europe by the Cali cartel. After "Operation Cornerstone" , begun in 1991, it took another 14 years before the Cali cartel's cocaine shipments could finally be severely disrupted.

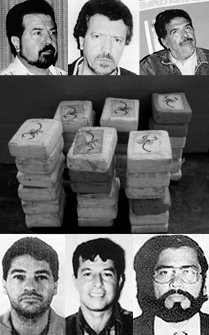

Arrests

Between June and July 1995, six of the seven leaders were arrested. Gilberto was arrested hidden in his home, Henry Loaiza, Victor Patino and Phanor Arizabaleta surrendered to the investigators, José Santacruz Londoño was arrested in a restaurant and a little later Miguel Rodriguez was arrested in a commando. The still powerful Cali cartel operated for a time out of prison through a covert chain of command. The Rodriguez brothers were extradited to the USA in 2006 and convicted in Miami / Florida for conspiracy and cocaine import into the USA. As a result of their confession, they pledged to pay fines of $ 2.1 billion in assets, with the deal relating solely to drug deals and no further cooperation on their additional possessions. Colombian officials raided the Drogas la Rebajas pharmacy chain and replaced 50 of the 4,200 employees for belonging to the Cali cartel. The Cali cartel dissolved and its business activities were taken over by the Mexican drug mafia.

Successor organizations

The Cali cartel existed until 1995 and de facto ended with the arrest of the Orejuela brothers. In its place came the Norte del Valle cartel, some smaller organizations such as the so-called "baby cartels" and the paramilitary AUC forces. In 2006, the Norte del Valle cartel in Colombia went down in a bloody feud and the AUC was demobilized. The BACRIM syndicate ( Bandas Criminales Emergentes ) belongs to the third generation of the Colombian drug organizations ( Los Rastrojos , Oficina de Envigado and the powerful Urabeños organization ), which has a networkable structure and has not yet been broken up. Medellín is still the center of drug trafficking.

literature

- Alexander Niemetz : The Cocaine Mafia. Bertelsmann, Munich 1990, ISBN 3-570-04411-4 .

- Myléne Sauloc, Yves Le Bonniec: Tropical Snow - Cocaine: The cartels, their banks, their profits, an economic report . Rowohlt, Reinbek b. Hamburg 1994, ISBN 3-498-06291-3 .

- Ciro Krauthausen: Modern Violence in Colombia and Italy. Campus Verlag, Frankfurt 1994, ISBN 3-593-35768-2 .

- Ron Chepesiuk: The Bullet or the Bribe: Taking Down Colombia's Cali Drug Cartel , Praeger Frederick, 2003, ISBN 0-275-97712-9 .

- Ron Chepesiuk: Drug Lords: The Rise and Fall of the Cali Cartel. Milo Books, 2005, ISBN 1-903854-38-5 .

- Enid Mumford: Dangerous Decisions: Problem Solving in Tomorrow's World . Springer-Verlag, 1999, ISBN 0-306-46143-9 .

- Felia Allum, Renate Siebert: Organized Crime and the Challenge to Democracy. Routledge, 2003, ISBN 0-415-36972-X .

- Richard Davenport-Hines: The Pursuit of Oblivion: a Global History of Narcotics . WW Norton & Company , 2004, ISBN 0-393-05189-7 .

- Nicholas Coghlan: Saddest Country: On Assignment in Colombia. McGill-Queen's University Press, 2004, ISBN 0-7735-2787-7 .

- James P. Gray: Why Our Drug Laws Have Failed and What We Can Do About It: A Judicial Indictment of the War on Drugs. Temple University Press, 2001, ISBN 1-56639-860-6 .

- Juan E. Méndez: Political Murder and Reform in Colombia: The Violence Continues. Americas Watch Committee (US), 1992, ISBN 1-56432-064-2 .

- Patrick L. Clawson, Rensselaer W. Lee: The Andean Cocaine Industry. Palgrave Macmillan, London, 1998

- Manuel Castells: End of Millennium- The Information Age: Economy, Society and Culture. Vol. III Blackwell Publishing, Cambridge, UK 1997, ISBN 0-631-22139-5 .

- Kevin Jack Riley: Snow Job? The War Against International Cocaine Trafficking. Transaction Publishers, 1996, ISBN 1-56000-242-5 .

- Dominic Streatfield: Cocaine - An Unauthorized Biography. Thomas Dunne Books, 2002, ISBN 0-312-42226-1 .

- William Avilés: Global Capitalism, Democracy, and Civil-Military Relations in Colombia. State University of New York Press, 2006, ISBN 0-7914-6699-X .

Web links

- Elaine Shannon Washington "New Kings of Coke," Times Magazine, 1991.

- John Moody, Pablo Rodriguez Orejuela & Tom Quinn. "A Day with the Chess Player," Time Magazine, 1991.

- Kevin Fedarko. "Outwitting Cali's Professor Moriarty," Time Magazine, 1995.

- Colombia takes charge of pharmacy chain linked to Cali cartel, USA Today, 2004.

- Elizabeth Gleick, "Kingpin Checkmate," Time Magazine, 1995.

- "Transcript of Press Conference Announcing Guilty Pleas by Cali Cartel", United States Department of Justice, 2006.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c Myléne Sauloc, Yves Le Bonniec: Tropical Snow - Cocaine: The cartels, their banks, their profits, an economic report. Rowohlt, Reinbek b. Hamburg 1994, p. 103.

- ↑ a b Myléne Sauloc, Yves Le Bonniec: Tropical Snow - Cocaine: The cartels, their banks, their profits, an economic report. Rowohlt, Reinbek b. Hamburg 1994, p. 102.

- ↑ druglibrary.org Major trafficker & Their Organizations, The Cali mafia, DEA Publications

- ↑ Padre del ex presidente colombiano Álvaro Uribe era “un reconocido narcotraficante” argentinatoday.org. Retrieved October 25, 2018 (Spanish)

- ↑ Ron Chepesiuk: The Bullet or the Bribe: Taking Down Colombia's Cali Drug Cartel, Praeger Frederick, 2003, p. 23

- ↑ Ron Chepesiuk: The War on Drugs - An International Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO, 1999, ISBN 0-87436-985-1 , p. 95.

- ↑ Myléne Sauloc, Yves Le Bonniec: Tropical Snow - Cocaine: The cartels, their banks, their profits, an economic report. Rowohlt, Reinbek b. Hamburg 1994, p. 64.

- ↑ Myléne Sauloc, Yves Le Bonniec: Tropical Snow - Cocaine: The cartels, their banks, their profits, an economic report. Rowohlt, Reinbek b. Hamburg 1994, p. 93.

- ↑ Myléne Sauloc, Yves Le Bonniec: Tropical Snow - Cocaine: The cartels, their banks, their profits, an economic report. Rowohlt, Reinbek b. Hamburg 1994, p. 97.

- ↑ articles.latimes.com The man who took down Cali, Los Angeles Times, February 24, 2007

- ↑ Information Paper on “Los Pepes”. (PDF) gwu.edu, NS Archive

- ↑ telegraph.co.uk Revealed: The secrets of Colombia's murderous Castaño brothers, The Telegraph, November 7, 2008

- ^ Charles Krause: Columbia's Samper and the Drug Link. In: pbs.org. March 20, 1996, archived from the original on October 26, 2013 ; accessed on July 6, 2020 (English).

- ↑ aceproject.org narco-trafficking, ACE The Electoral Knowledge Network . aceproject.org. Accessed April 27, 2017 (English)

- ^ Constantine-institute.org Professor Tom Constantine, The Constantine Institute

- ^ Judge James P. Gray: Why our Drug Laws have failed and what we can do about it . Temple University Press, Philadelphia 2001, p. 85.

- ↑ druglibrary.org Major trafficker & Their Organizations, The Cali mafia, DEA Publications

- ↑ derechos.org Los Jinetes de la Cocaina, Capítulo V Los negocios

- ↑ osdir.com ( Memento of November 8, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) Subject: British intelligence Mossad DOPE, INC Cartel Drug, Oil Wars on Git.Net

- ↑ time.com The Cali Cartel: New Kings of Coke, Time Magazine, July 1, 1999

- ↑ virginiavallejo.com ( Memento of October 13, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) Virginia Vallejo Homepage, Biografía

- ↑ elespectador.com Capturan al testaferro de los Rodríguez Orejuela, El Espectador, March 21, 2009

- ↑ “Nosotros no matamos jueces… los compramos” in page no longer available , search in web archives: mre.gov .

- ↑ time.com Rocked by Scandal. Samper's Presidency is in peril as an aide says his boss took campaign contributions from druglords. Time Magazine, Aug. 14, 1995

- ↑ Patrick L. Clawson, Rensselaer W. Lee: The Andean Cocaine Industry. Palgrave Macmillan, London 1998, p. 61.

- ^ “ The Cali cartel on the other hand, practiced 'social cleansing'; that is, randomly killing hundreds, maybe thounsands, of 'desechables' (discardables), who, in the drug traffickers view, included the prostitutes, street children, beggars, petty thieves and homosexuals ”. in Manuel Castells: End of Millennium, The Information Age: Economy, Society and Culture, Vol. III Cambridge, UK 1997, p. 204.

- ↑ Myléne Sauloc, Yves Le Bonniec: Tropical Snow - Cocaine: The cartels, their banks, their profits, an economic report. Rowohlt, Reinbek b. Hamburg 1994, p. 105.

- ↑ Publicidad, Grupo de 'limpieza social' siembra el terror en Yumbo y Jamundí. English: The social cleansing group sows the seeds of horror in Yumbo and Jamundí. In: caracol.tv. March 12, 2009, archived from the original on February 7, 2014 ; accessed on July 6, 2020 (Spanish).

- ↑ ( Page no longer available , search in web archives: Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina y el Caribe, España y Portugal, Ciudad y política. Cali, Colombia, 1987–2007 ) (PDF)

- ↑ anncol.eu ( Memento of October 7, 2009 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ a b Myléne Sauloc, Yves Le Bonniec: Tropical Snow - Cocaine: The cartels, their banks, their profits, an economic report. Rowohlt, Reinbek b. Hamburg 1994, p. 109.

- ↑ Spanish Dirección de Policia Judicial e Investigación

- ↑ elcolombiano.com

- ↑ Espectador: Los muertos que aún guarda el río Cauca - The dead that the Rio Cauca now holds, June 15, 2008

- ^ El Colombiano, Series, Un puerto de cadáveres en Marsella - A port of the dead in Marsella

- ↑ Ron Chepesiuk, Andres Pastrana Arango: The War on Drugs: An International Encyclopedia . ABC-CLIO, 1999, p. 165.

- ↑ derechos.org

- ↑ a b Patrick L. Clawson, Rensselaer W. Lee: The Andean Cocaine Industry. Palgrave Macmillan, London 1998, p. 58.

- ↑ start.umd.edu

- ↑ Ron Chepesiuk, Andres Pastrana Arango: The War on Drugs: An International Encyclopedia . ABC-CLIO, 1999, p. 95.

- ↑ According to the page no longer available , search in web archives: eltiempo.com it was the Cuerpo elite who killed Gustavo Gaviria

- ↑ semana.com

- ↑ frontline: drug wars: thirty years of america's drug war | PBS

- ^ History of the ICE Investigation into Colombia's Cali Drug Cartel and the Rodriguez-Orejuela Brothers. In: ice.gov. United States Immigration and Customs Enforcement , March 2005, archived from the original on September 16, 2008 ; accessed on July 6, 2020 (English).

- ↑ druglibrary.net

- ↑ contralinea.com.mx

- ^ Colombia takes charge of pharmacy chain linked to Cali cartel , USA Today, December 17, 2004

- ↑ 20 Years After Pablo: The Evolution of Colombia's Drug Trade, Insight Crime

- ↑ 'El Chapo' Guzmán's key role in the global cocaine trade is becoming clearer . businessinsider