Lobbying

Lobbying , lobbying or lobbying is a term taken from the English ( lobbying ) for a form of the representation of interests in politics and society, in which interest groups ("lobbies") - especially by cultivating personal connections - the executive , the legislative and other official branches Trying to influence bodies. Lobbying also influences public opinion through public relations . This is mainly done through the mass media .

The term has negative connotations (secondary meanings), so interest groups do not appear under this term. Common names for lobbying are, for example, public affairs , political communication and political advice . Companies and organizations sometimes have an office in the capital or a representative in the capital , but also offices at the state governments.

In 2006, Thomas Leif and Rudolf Speth introduced the term Fifth Power for lobbying in analogy to the term Fourth Power for the mass media , which, however, is viewed by other authors as exaggerated. Thilo Bode headlined the glyphosate scandal 2017 in the Blätter für Deutsche und Internationale Politik , in the October 2018 issue: "Lobbyism 2.0: The industrial-political complex."

Concept history

The term goes back to the lobby of Parliament (for example the lobby in front of a plenary hall ) - depending on the historian's origin, the “ lobia ” of the Roman Senate, the “lobby” of the British House of Commons or the US - American Congress - in which representatives of various groups reminded parliamentarians of the possibility of voting out and also offered advantages or disadvantages for certain behavior.

In terms of verbatim history , lobbyism also ties in with its historical pre-forms of antichambring (the search for influence in the antechamber) and the late medieval activity of the “ courtiers ”. The slightly negative evaluation of the term in German-speaking countries may be due to this (and / or the lack of binding, transparency-creating rules for lobbying work).

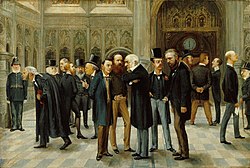

Caricature of the lobby in the House of Commons ( Vanity Fair , ca.1886)

Definition

A uniform understanding of lobbyism has so far not been able to establish itself in the scientific literature. Numerous definitions are still in competition, each based on different aspects. Rinus van Schendelen assigns lobbying a completely unorthodox character and locates it exclusively on an informal level, while Günter Bentele emphasizes the legal and moral norms of lobbying and Leo Kißler focuses on institutionalized forms of influence such as (1) formal contacts [n ] between associations and 'related' MPs within the framework of working groups and contact groups in parliamentary groups, (2) parliamentary consultation hours , (3) inquiry commissions (...) and (4) non-public hearings of interest representatives by the Bundestag committees . Scott Ainsworth, on the other hand, sees lobbyists as a service point for political decision-makers who provide information overnight if necessary, while Klaus Schubert and Martina Klein emphasize the exertion of pressure as an essential element.

After analyzing 38 approaches, Stefan Schwaneck forms four categories into which lobbyism definitions can largely be classified:

- Broad definitions that roughly outline lobbying, but do not specify its manifestations.

- Cumulative definitions that list at least two of the three core elements of information gathering, information exchange and influencing.

- Definitions that explicitly mention lobbying activities or add concrete features to the term lobbying.

- Alternative definitions that set clearly different priorities or reduce lobbying to individual characteristics.

The first category includes approaches such as that by Carsten Bockstette, who defines lobbyism as an attempt to influence decision-makers by third parties . Such an approach, as well as equating it with lobbying, is controversial because, depending on how it is interpreted, it can also include non-political activities that are not commonly associated with lobbying (e.g. advertising , public relations ). In a more focused way, Peter Köppl regards lobbying as influencing political decisions by people who are not involved in these decisions, and Hans Merkle emphasizes the targeted influencing of decision-makers in politics and administration. Alexander Bilgeri's approach also falls into this category, who describes lobbying as a direct or indirect influence on political processes of organizations by external participants - also with the help of bases of power - in order to pursue a specific purpose .

Cumulative definitions lay down e.g. B. Manfred Strauch and Iris Wehrmann. Strauch sees lobbying as a method and the application of this method to influence the decision-making centers and decision-makers within the framework of a strategy to be prepared or already defined (...) , which is based on the collection, processing and exchange of information as its most important instruments. Practically oriented, Wehrmann declares lobbying to be an exchange of information and political support against the consideration of certain interests in state decision-making .

An example of the third category is the approach of Clive S Thomas, who, in addition to attempting to exert influence on a specific occasion, sees the networking of actors as an equally important goal of lobbying, as personal relationships can have a positive effect on future decisions. Ulrich von Alemann and Rainer Eckert define lobbying as the systematic and continuous influence of economic, societal, social or even cultural interests on the political decision-making process .

Rinus van Schendelen presents shortened definitions, describing lobbyism in a minimal description as an informal exchange of information with authorities and in a maximal description as an informal attempt at influencing authorities , but ignoring institutionalized procedures. Like a later approach by van Schendelen, which introduces lobbyism as a collective term for unorthodox actions by interest groups with the aim of government action in the interests of these interest groups, this understanding of the term leaves out parliaments and elected representatives as a target group of lobbyist influence. Even Thomas Leif and Rudolf Speth reduce lobbying to influence the government . Alternative approaches that fall outside the rest of the structure are presented by Bruce C Wolpe, who understands lobbyism as the political management of information, and Rune Jørgen Sørensen, who recognizes lobbyism as a screening mechanism for voter interests.

Against the background of the numerous different approaches, Schwaneck suggests the use of a broad definition that captures the characteristics associated with lobbying in the literature and can serve as a framework. Studies with a certain focus can be located within this framework, a narrower definition can be achieved by omitting indirect exposure attempts:

“Lobbying describes direct and indirect attempts by representatives of social actors to influence political decision-makers in the legislative and executive branches as well as other stakeholders involved in the political decision-making process through information, argumentative conviction or the exertion of pressure in order to anchor more or less particular interests in laws or state action . The acquisition, analysis and strategic transfer of information, which can be exchanged for political influence or other relevant information in formal and informal contexts, are of fundamental importance in lobbying as long as the line to corruption or other prohibited practices is not exceeded. "

Doer

Business associations , employers' associations , trade unions , churches , non-governmental organizations and other associations as well as larger companies and political groups bring their interests into the political opinion-forming process in a targeted manner and provide their members and the public with relevant information . This enables them to adapt to expected political decisions.

However, law firms, PR agencies, think tanks and independent political consultants have also specialized as external lobbyists in establishing connections, procuring information or placing issues in the interests of their clients. Law firms are increasingly being commissioned because they can protect themselves from journalists through professional secrecy .

Lobbying process

Lobbying is a method of influencing decision-makers and decision-making processes as part of a strategy. It takes place primarily through information. It is often circumscribed by four characteristics:

- Information gathering,

- Information exchange,

- Influence,

- strategic direction of activity.

information gathering

Stakeholders gather information to gain insights into what policy makers are doing. The association headquarters and the association members are informed accordingly and evaluate the information. The evaluation takes place with regard to the effects of the project on the business activities of the members of the association. For effective lobbying, it is advisable not only to obtain information from publicly accessible sources, but also to obtain information informally at an early stage by cultivating interest-based relationships with decision-makers and other lobbyists.

Opinions (“lobby papers”) and suggestions for changes are then drawn up, mostly by the legal department or other specialist departments.

Influence

It is then the task of the lobbyist to present these amendments to the decision-makers and to place them in the relevant committees (“political advice”). The placement takes place in legitimate lobbying through argumentative influence on the decision-makers. The argumentative influence is successful if MPs and civil servants are dependent on specialist knowledge , often selectively prepared by those concerned and interested parties (" stakeholders "), in the difficult issues about which they have to make decisions in close succession becomes. In the case of civil servants, it can also happen that the lobbyists or consulting firms are trusted more than their in-house specialist expertise. The better the offices of parliamentarians are equipped with scientific staff , parliaments with their own scientific services or authorities with specialist officials, the more difficult it is for lobbyists to make themselves indispensable. Most states prohibit bribery and other benefits. However, it often happens that high-ranking decision-makers from politics or the executive (e.g. ministries) “change fronts”, i.e. give up their previous position and switch to an association, a company, a PR agency or a law firm.

Another field of influence is the skillful placement of industry-leaning experts in public hearings, in consulting firms or their use in the preparation of expert opinions.

public relation

As part of their public relations work , lobbyists try to influence public opinion through the media. The methods used include issuing press releases and advertising campaigns , in which the authorship is mostly made public, but also methods in which the authorship is to be partially concealed. For television, carriers of their own opinions are conveyed as guests in panel discussions , talk shows or as interview partners, and hidden messages in an ARD soap opera were financed.

In order to influence them via print media, entire interviews are left to them, media partnerships are established with newspapers, and specialist articles and rankings are written for magazines. Journalists are offered discounts, journalists reporting on cars are occasionally left with longer-term access, background discussions and information events are sometimes organized in connection with luxury events.

If PR campaigns are used to pretend that they are being carried out by private individuals, it is called astroturfing . This includes writing letters to the editor, forum entries and blogs, but also attempts to place or prevent statements in Wikipedia articles or the establishment of “citizens' groups”.

Interest groups look after groups of visitors in offices in the capital and invite them to events. The lobby association generally tries to be “the window” of its industry in the capital and to represent it.

In some cases, teachers are given free teaching materials that are well prepared but are also seen as influencing.

Lobbying in individual countries

Situation in the Federal Republic of Germany

As early as 1956, the Federal Constitutional Court ruled in the so-called KPD judgment that “there is no doubt that extra-parliamentary actions of various kinds are conceivable that can serve a legitimate influence on parliament, especially as far as they are intended to be the MPs to inform about the opinions of the electorate on certain political issues. It is therefore constitutionally unobjectionable that 'interest groups' seek to influence the members of parliament ”.

Art. 8 and Art. 9 of the Basic Law guarantee the right to freedom of assembly and association, thus protecting the association of interested parties in clubs and associations. Article 5.1 of the Basic Law enables the development of political attitudes and the freedom to represent different interests. There is also the in Art. 17a existing right of petition . Lobbying in Germany is protected and legal by the constitution. Many of the issues in lobbying are in the public eye.

In discussions such as nuclear and solar energy , biotechnology , copyright / file sharing or software patents , it is criticized that industry and large corporations can enforce laws at the federal or EU level through massive lobbying that are in their interests, but not in the interests of medium-sized companies or the consumer. The same accusation is directed against some environmental associations , social associations and churches , which also - in the guise of general interest - represent particular interests . The former President of the Federal Constitutional Court, Hans-Jürgen Papier , warned that “real equality of arms between the various social groups in the pursuit of their interests through lobbying” could hardly arise and that interests that were less well represented would not come into play.

Former MP Raimund Kamm describes the situation as follows:

“As soon as someone is elected a member of parliament or then also a minister, his communication and conversation partners change fundamentally. 'Workers' representatives' or Greens are then invited and courted by the Chamber of Commerce , entrepreneurs and other unilaterally interested parties. An increasing part of the discussions by elected politicians takes place with professional lobbyists. This also flatters the young, inexperienced representative. "

The President of the German Bundestag keeps the public list of the registration of associations and their representatives . The number of entries fluctuates, 2136 associations were registered in June 2010, 2079 in July 2012, 2221 in December 2014. Due to the voluntary nature of the admission and the narrow definition of "association", the list does not cover the entire spectrum of lobbying in the German Bundestag . In the 16th electoral term of the German Bundestag (2005–2009) there were several parliamentary initiatives aimed at improving the transparency of the interaction between politics and interest representatives. In their programs for the 2009 federal election , the SPD , Bündnis 90 / Die Grünen and the Die Linke party finally included the call for a mandatory lobby register to be set up . Of the 2221 lobby groups at the end of 2014, 575 had received a house ID from the German Bundestag that gave them access to the properties. Just as many house IDs were obtained from previously unknown lobbyists from the parliamentary directors of the parliamentary groups in a process that was previously kept secret. After lengthy legal disputes, in autumn 2015 the Bundestag administration published the number and names of the lobbyists who had obtained the ID cards with the help of the parliamentary groups: 1,111 representatives from associations, companies, law firms and agencies. In February 2016, the Bundestag's Council of Elders decreed that company representatives will no longer receive house cards in the future. In 2017, the 630 members of the Bundestag faced 706 lobbyists with a Bundestag ID card.

According to rough estimates there are 5,000 lobbyists in Berlin, statistically eight for each MP. Norbert Lammert already lamented their considerable and increasingly well-organized influence.

A special form of lobbying “in the orbit of corruption” ( Hans Herbert von Arnim ) became public knowledge in 2006: people from the private sector, associations and interest groups who continue to be employees of their actual employer and are paid by them temporarily work as external employees in German federal ministries . According to the Federal Government, however, political influence on decisions by the ministries is excluded.

The teaching materials provided by business associations in the subject of economics are criticized for being “scientifically and politically biased”.

In the Federal Republic of Germany the pharmaceutical industry and the energy industry are regarded as sectors with particularly great lobbying power.

The energy industry, in particular the four large energy groups in Germany ( RWE , EON , EnBW and Vattenfall ), had to first phase out nuclear energy under the red-green in 2000 with the "Agreement between the Federal Government and the Energy Supply Companies" ( atomic consensus ) Accept the government of Gerhard Schröder. Then she worked with the help of her lobbying organizations, such as B. the German Atomic Forum (DAtF) and the Nuclear Technology Society (KTG) , and supported by nuclear power proponents from politics for a revision of the "atomic consensus". The nuclear lobby tried to achieve a change of opinion in the run-up to the 2009 federal election; in autumn 2010, after extensive media campaigns, it was able to push through the lifetime extension of German nuclear power plants . Since March 2011, the nuclear lobby has been trying to delay or reverse the second nuclear phase-out under Angela Merkel.

One of the most powerful networks is “Das Collegium”, which as of 2015 brings together lobbyists from a total of 46 international companies and associations in Berlin.

In 2017, among other things, the Dieselgate and Cum-ex scandals, with losses in the billions for the state, were largely attributed to the influence of lobbyists. LobbyControl activists concluded from the developments that efforts to achieve binding regulations for lobbyists in Germany had come to a standstill under Merkel III's cabinet .

Situation in Austria

In the Second Republic (since 1945), the political balance of interests has mainly been done at the level of the social partners . Therefore, the labor, economic and agricultural chambers at federal and state level (the interest groups for employees, employers and farmers with compulsory membership) and the trade union federation are the dominant interest groups; their power is of essential importance for the parliamentarism of Austria. Decisions have been and are being coordinated in parallel on the levels of the social partners, the federal and state governments and the legislative bodies. Triggered by Austria's accession to the EU, significant liberalization and privatization steps and the EU expansion, however, the demands placed on companies and their management are changing.

The Austrian Public Affairs Association (ÖPAV) (formerly the Austrian Public Affairs Association) was founded in September 2011 as an association of public affairs managers in agencies, companies, associations and NGOs. When it was founded, the ÖPAV adopted a strict code of conduct and sees itself as the mouthpiece of the entire public affairs industry in Austria. When it was founded, the ÖPAV became the largest such association in the country.

ALPAC (Austrian Lobbying and Public Affairs Council) is the influential association of the owners of lobbying and political consulting companies in Austria. A prerequisite for membership in this exclusive group is many years of experience as a politician, political advisor, domestic policy editor, interest representative or diplomat.

Situation in Switzerland

Switzerland knows various strongly institutionalized forms of political balance of interests. These include the social partnership , the consultation process and the expert commissions. In addition, lobbyists can sit in parliament largely unhindered (today, however, they are obliged to publish); it was previously used by farmers, and today it is used by organizations in the economy and the health sector.

Government members must dissolve their interests and secondary income at the national level (for example according to the incompatibility regulations for members of the Federal Council in Art. 144 of the Federal Constitution ), while they are expressly permitted at the cantonal level in some cases because of the militia system .

In the 1980s, a critical discussion about institutionalized interest representation arose, especially in the mass media and in academia, which led to various, rather modest reforms. Each member of parliament has the opportunity to designate two people who have privileged access to the lobby of the parliament. In an investigation of the guest lists from 2004 to 2011 it was found that a core group of around 220 lobbyists can be found regularly. The total number is much higher as ex-parliamentarians have free access to the foyer and do not need a guest pass. The guests received by the parliamentarians are to be accompanied by the council members in the future, with which the access should be restricted a little and the control increased.

After a confidential strategy paper from a PR agency became public in 2016, the Swiss media increasingly showed the role of this type of lobbyist, who often work undercover.

Situation in the European Union

→ European interest representation

Character of EU lobbying

Legislation in the Member States cannot be separated from that in the European Union. In many cases - as with the Council of the EU in Brussels - there is a personal identity with members of the member state government. Furthermore, European directives require the subsequent implementation in national law. The European argumentation can usually be continued seamlessly in national bodies.

The heterogeneity of economic interests increases at the European level. Brussels legislation affects 28 member states (as of 2014). In addition to the needs of individual companies or industries, specific national market situations, corporate philosophies and interests must also be taken into account. The number of people to be represented and the spectrum of divergence are increasing. The interests to be safeguarded by the associations are therefore even broader and more complex than at the national level. At the same time, the influence on European legislative acts takes place in very different forms at the national as well as at the European level. In empirical studies, the system of EU interest mediation has been described using the metaphor of the “mosaic”, “which is characterized by the parallel existence and persistence of different structural properties”.

Under certain circumstances, it can therefore be helpful for the respective company if, in addition to indirect lobbying via the industry association, it brings its individual concerns directly to the decisive points. The branches of the companies in Brussels - as in the member states - are mostly low-staffed or serve as a bridgehead and an extended arm, but not as an operational unit. Medium-sized companies rarely have such branches. As a result, company representatives often lack the necessary staff to be able to cushion extensive “zeitgeist initiatives” by the legislature, such as the tobacco advertising ban at European level or the mentioned can deposit at national level. For this reason, companies are increasingly using consultants to represent their interests. Following the US model, large international law firms and lobbying firms are now on the advance in the sector by bringing foreign companies to the German, Austrian or European market - mostly with the help of ex-politicians and specialized lawyers in their ranks introduce or make German or Austrian companies heard in political bodies.

Due to the poor scientific support in comparison to the parliaments of the member states, members of the European Parliament also use lobbyists for their detailed knowledge. The risk that the information transmitted is incomplete or partially selected is reduced by the fact that the EU institutions hear a large number of lobbyists from various interest groups. Nevertheless, lobbying is not fundamentally rejected, even by critical parties. MPs are often 'fed' with free offers by lobby organizations. According to analyzes by the Austrian MEP Hans-Peter Martin , the equivalent of offers such as travel, dinner or cocktail receptions made by lobbyists can reach up to € 10,000 per week.

Transparency and Register

More regulation of lobbying work is being discussed at EU level. In June 2008 the EU Commission set up a (initially) voluntary register of lobbyists. In it, companies and associations should disclose income from and expenditure for lobbying work. In May 2008, however, the European Parliament spoke out in favor of introducing a general mandatory register for EU lobbyists, similar to the one that exists in the USA. So far, however, the EU Commission has opposed a mandatory lobby register.

There is therefore no registration requirement to date. Rather, there is an incentive system for registration. In the European Parliament, they are granted access to the building with a badge. This can be found in Section 9 of the Rules of Procedure. In October 2007, 4,570 people were registered as lobbyists at the European Parliament; associated with this was easier access to the parliament buildings.

As part of the transparency initiative launched in 2005 by Commissioner and Vice-President Siim Kallas, the Commission will publish a voluntary internet register for lobbyists on 23 June 2008. You are called upon to register and thus identify your interests, customers and finances. At the same time as registering, they sign a code of conduct that has been drawn up together with the interest groups. A planned control mechanism should check the information. However, the introduction is only a milestone: In the long term, it is planned to create a single register together with the EU Parliament. Parliament would then only allow registered lobbyists into the building. In fact, the previously voluntary register would then be mandatory - even without a law. In 2008 the EU introduced a lobby register.

The joint register of interest representatives at the European Parliament and the European Commission ( transparency register ) went into operation on June 23, 2011. All organizations, companies and self-employed who exercise activities with the aim of directly or indirectly influencing political decision-making processes or decisions of the EU institutions are invited to register. The registration in the transparency register requires the disclosure of the total annual turnover from lobbying work, optionally also only the specification of a turnover size class (e.g.> = 100,000 - <150,000 €) as well as the relative share of named clients / customers in this turnover, optionally also the Sales size class (e.g. company XY <50,000) ahead (for details, see the guidelines on financial information). The obligation to provide this information in a comprehensive and truthful manner results from a code of conduct to which the interest representatives must submit when they are entered in the register. However, there is no obligation to register, which has been criticized from many sides. In 2014 it was estimated that 15,000 to 25,000 lobbyists were working in Brussels.

On November 25, 2014, the European Commission made the decision to use a new transparency initiative to make events within the EU Commission even more transparent. Since December 2014, all commissioners, their staff and directors-general of the individual Commission departments are obliged to make meetings with interest representatives and lobbyists public. The meetings listed can be found on the website of the European Commission.

On January 31, 2019, the EU Parliament passed binding rules on the transparency of lobbying. In an amendment to its Rules of Procedure, Parliament stipulated that MEPs involved in drafting and negotiating laws must publish their meetings with lobbyists online.

Lisbon Treaty

Since the Treaty of Lisbon came into force , European lobbyism has been increasingly associated with participatory democracy . Would refer Art. 11 TEU expressly to representative associations out. The fact that this could also include companies is shown in practice by the EU subsidiary body, the European Economic and Social Committee .

Case studies

Swabian children

In their homeland, the Swabian children were exempted from compulsory schooling every year . In the Kingdom of Württemberg , compulsory schooling there since 1836 did not apply to foreign children. This affected all Swabian children. The extension of compulsory schooling to these children, which has repeatedly been politically demanded, was prevented by an Upper Swabian farmers' lobby until 1921.

Car lobby in Brussels

An example of lobbying at EU level is the car lobby in Brussels. While car manufacturers lobbyists are trying to raise the EU's planned limit of 120 g CO 2 / km, environmental groups are working to enforce this value. After initial difficulties, the EU Parliament passed a resolution on stricter emissions standards in November 2013. The regulations stipulate that from 2020 onwards, the majority of new vehicles may not exceed the limit of 95 g / km. This value should be based on the manufacturer's entire fleet. However, not all cars have to comply with the limit value. A maximum of 130 g / km applies to five percent of the vehicles. This gives manufacturers the opportunity to have low-emission models counted towards their carbon footprint several times. This special regulation means that high-horsepower upper-class models from one manufacturer can only meet the emission limit specification later, because electric cars from the same manufacturer also ensure a balanced climate balance. As a result of the new limit values, the CO 2 emissions of a manufacturer's new vehicle fleet must not exceed the average value of 95 grams per kilometer from 2020. In 2012 the average value in Europe was 136.1 g / km, in Germany it was even 141.8 g / km. However, if the cars still emit more than the permitted 95 g / km from 2020, the EU regulation provides for penalties for the manufacturers. The fine would amount to 95 euros per gram and vehicle. If, for example, the CO 2 emissions of all cars from one manufacturer were to be 105 g / km in 2020, the car manufacturer would have to pay a fine of 950 euros for each car sold. In addition to the EU, other countries in the world have also set a CO 2 limit by 2020. In the USA, for example, a limit of 121 g / km applies, from 2025 it will be 93 g / km, the Chinese government has agreed on a value of 117 g / km and Japan on 105 g / km.

Finance

Another example of the great power of specialized industry lobbies within the EU network of institutions is the strong involvement of the financial sector in the regulation of the financial markets. Accordingly, banks currently make up the overwhelming majority of members in the official advisory body of the EU Commission. For example, Deutsche Bank and Commerzbank are to send representatives to Brussels. However, there are only two consumer advocates and trade unionists only one on the forty-member body. MEPs in the European Parliament have already asked “ civil society ” for help on this occasion .

In the course of the financial crisis from 2007 , the European Union for the regulation of the financial markets increasingly pointed to an imbalance in lobbying in favor of the financial industry. The lobby organization Finance Watch was founded at the end of June 2011 in a cross-party initiative by MEPs in the European Parliament .

Tobacco lobby

The affair surrounding ex-health commissioner John Dalli and the EU tobacco directives have revealed an influence of the financially strong tobacco lobby on EU dignitaries. After demanding a € 60 million bribe, John Dalli had to leave his office. In order to represent its interests, the tobacco lobby had sought contact with Dalli's personal circle. Michel Petite left his position as chairman of the ethics committee of the EU commission under pressure from lobby control and other lobbyists. He is said to have used his contacts in the Commission to represent the interests of the law firm Clifford Chance, which Philip Morris International has as a client.

Biofuels

In 2009 the lobby control association criticized the Association of the German Biofuel Industry e. V. for measures of covert public relations work (so-called astroturfing ). The PR agency Berlinpolis had u. a. Placed alleged letters to the editor in the newspapers Junge Welt , FAZ , Frankfurter Rundschau and Focus Online . Berlinpolis's client was the lobby agency European Public Policy Advisers GmbH ( EPPA for short ).

Monsanto glyphosate

Some examples also only suggest the suspicion that lobbyists are exerting influence in political decisions without searching for or finding evidence. At least it is very difficult to assign them to individual politicians. In 2017 , the German Agriculture Minister Christian Schmidt approved a further approval of the controversial herbicide glyphosate in the EU until 2022, completely surprising and against the agreement of the cabinet and the rules of procedure of the Federal Government. Schmidt justified his yes with "important improvements for the protection of the flora and fauna" and admitted that he had made up his mind alone. He did this even though around 73% of Germans were in favor of a ban. The impetus could also have come from the management level of the ministry: According to this, the responsible specialist department for plant protection, Minister Christian Schmidt, recommended on July 7th 2017 to check whether the EU commission's proposal could be "independently" without the consent of the SPD-led environment ministry could agree. The cabinet rejected a request from the ministry to this effect. Thilo Bode headlined this in the newspaper for German and international politics , in the October 2018 issue: Lobbyism 2.0: The industrial-political complex. There has been ample opposition in the EU to the extension to break free from an industrial agrochemical "poisoning farmers and ecosystems," according to a comment in the French newspaper Le Monde . The company Monsanto is the world's largest producer and in some media, the Minister was then called Monsanto's chief lobbyist or lobbyist. However, there was also active lobbying in Brussels: The responsible EU health commissioner Vytenis Andriukaitis from Lithuania was impressed after the vote: “Can't you see that on our faces that we have won?” How extensive Monsanto's lobbying can be , showed in 2019: According to media reports, the glyphosate manufacturer is suspected of secretly funding studies in Germany that were then used as arguments against politicians.

Areas of action of lobbyism

There are essentially five fields of action in which organized interests are to be enforced through lobbying:

- in the economic sector and in the world of work

- in the social area

- in the field of leisure and recreation

- in the field of religion, culture and science

- in the socio-political cross-sectional area

Organizations and agencies

According to lobby control , there are more than 40 major influencers in the center of Brussels in the immediate vicinity of central EU institutions: business associations (V), agencies (A) or direct representations of large corporations (K):

"Neutral" negotiation venues away from the EU institutions are located in the following buildings, among others:

| Bibliothèque Solvay |

| Bastion Tower |

| Concert Noble |

public perception

The lobbyism is based on the " fourth power " (media) also referred to as the "fifth power", since the politics of interests as well as the media have an influence on the state authority . In contrast to the institutionalized authorities , lobbyists are not subject to any clear legal regulations.

Lobbying can lead to corruption and thus unauthorized influence on legislation. One form are so-called "information events" organized by lobby groups for parliamentarians and civil servants, which are combined with free meals and occasional trips for the invited. This is not uncommon in Brussels, but also in Berlin. The aim is to win the people's representatives for their own interests.

There are proven cases in which funds and services flowed in order to obtain certain voting behavior from individual parliamentarians. However, the extent of this corruption cannot be determined. That is why there are efforts at all levels of the public service to prevent this type of corruption. For example, the members of the EU Commission are obliged to declare gifts with a value of 150 euros or more. The list of these gifts can be viewed on the website of the EU Commission. The same applies to all members of the public service.

Lobbyism is therefore always caught between the legitimate representation of interests and the possible threat to basic democratic principles. Due to the complex economic structures and subject areas, which in many cases overwhelm the legislature in its assessment options, lobby groups still have an important function, in particular by providing information. Those involved in the legislative process in Europe therefore seek - as they have for a long time in the USA - openly to talk to business representatives, associations and lobbyists in order to obtain comprehensive information on the economic and legal aspects of a project before making a decision.

In contrast to the American system, in Germany the term lobbyism is often perceived with negative connotations. In public opinion, politics is more often perceived as a victim of (interest groups) and lobbyists. Left-wing politicians often rate the influence of lobbyists as “rule of capital”, while the politically conservative camp is of the opinion that lobbyists undermine or even colonize the authority of the government. This is particularly due to the understanding of consensus, which strongly shapes German politics. In Germany, good politics is seen as the achievement of a mutually acceptable and fair compromise between different political positions. Associations that want to see their own sometimes very special goals and interests realized in politics are therefore perceived as a potential danger for reaching consensus.

This negative perception is unusual in that Germany has a high level of membership for associations, trade unions, NGOs, clubs, religious communities and other interest groups. These are usually assumed to represent the interests of their members in all areas and to lobby for them. In Germany, an above-average number of citizens are members of associations and often members of several interest groups. The fact that the general public perception of lobbying is still critical and mostly negative can be due to the frequent reports that the interests of the members are not recorded or manipulated in the interests of the lobby association top. The criticism of the ADAC is exemplary here .

See also

- Advocacy Coalition

- Agenda setting

- Antichamber

- Revolving door effect

- Evangelical office

- Influencer

- Catholic office

- Communication strategy

- Board of Trustees Indivisible Germany

- Lobbypedia

- Parliamentary evening

- Spin Doctor

- Transparency International with the Transparent Civil Society Initiative

- Environmental lobbyism

- Association of Catholic Nobles in Germany

- Administrative ethics

- Volkswartbund

literature

Essays

- Andreas Geiger: Economic aspects of lobbying in the EU. In: Journal for Policy Advice. Volume 2, Issue 3 (2009), p. 427.

- Geiger: EU lobbying and the principle of democracy. In: European business and tax law. (EWS), issue 7/2008, p. 257.

- Anda: Possibilities and limits of influencing politics. In: Axel Sell, Alexander N. Krylov: Interactions between economy, politics and society. Verlag Peter Lang, Frankfurt 2009, ISBN 978-3-631-58487-3 , pp. 273-278.

- Ulrich von Alemann , Florian Eckert: Lobbyism as shadow politics. In: From Politics and Contemporary History . 15-16 / 2006.

- Florian Eckert: Lobbyism - between legitimate political influence and corruption. In: Ulrich von Alemann (Ed.): Dimensions of political corruption. VS-Verlag, Wiesbaden 2005, ISBN 3-531-14141-4 .

- Thomas Faust: From the activating to the activated state? Lobbying between corruption and cooperation. In: Administration and Management. 5/2009, pp. 251-260.

- Tilman Hoppe: Transparency by law? A future lobbyist register. In: Journal for Legal Policy. 2009, 39, tilman-hoppe.de (PDF; 811 kB)

- Thomas Leif , Rudolf Speth: The fifth power. Zeit Online , March 2, 2006.

- Klemens Joos: Decisions without a decision maker? Process competence is the decisive success factor for reducing complexity in the representation of interests at the institutions of the European Union In: Silke Bartsch; Christian Blümelhuber (Ed.): Always Ahead in Marketing: Offensive, digital, strategic. Springer Gabler 2015, ISBN 978-3-658-09029-6 .

- Konstadinos Maras: Lobbying in Germany. In: APuZ . 3–4 / 2009, pp. 33–38.

- Hans-Jörg Schmedes: You can't see them in the dark. In: Berlin Republic. 3/2009, pp. 69-71.

- Hans-Jörg Schmedes: Dare to be more transparent? To the discussion about a legal lobby register at the German Bundestag . In: Journal for Parliamentary Issues. 3/2009, pp. 543-560.

Edited volumes and monographs

- Stefan Schwaneck: Lobbyism and transparency. A comparative study of a complex relationship. Publication series comparative political science, VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, Wiesbaden, 2019, ISBN 978-3-658-26898-5 .

- Klemens Joos: Convincing political stakeholders. Wiley-VCH Verlag, 2015, ISBN 978-3-527-50859-4 (also published in English: Convincing Political Stakeholders . 2016)

- Wolfgang Gründinger : lobbying in climate protection. The national structure of the European emissions trading system. VS Verlag, Wiesbaden 2012.

- Kim Otto, Sascha Adamek: The bought state. How corporate representatives in German ministries write their own laws. Kiepenheuer & Witsch, Cologne 2008, ISBN 978-3-462-03977-1 .

- Andreas Geiger: EU Lobbying Handbook. Helios Media, 2007, ISBN 978-3-9811316-0-4 .

- Ralf Kleinfeld, Annette Zimmer, Ulrich Willems (eds.): Lobbying. Structures, actors, strategies. VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, Wiesbaden 2007, ISBN 978-3-8100-3961-3 .

- Jörg Rieksmeier (Ed.): Practical book: Political mediation of interests: Instruments - Campaigns - Lobbying. VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, Wiesbaden 2007, ISBN 978-3-531-15547-0 .

- Thomas von Winter, Willems, Ulrich (Ed.): Interest groups in Germany. VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, Wiesbaden 2007, ISBN 978-3-531-14589-1 .

- Cerstin Gammelin , Götz Hamann : The pullers. Managers, ministers, media - how Germany is governed. 5th edition. Econ Verlag, Berlin 2006, ISBN 3-430-13011-5 .

- Thomas Leif, Rudolf Speth (ed.): The fifth power. Lobbyism in Germany. BpB, Bonn 2006, ISBN 3-89331-639-6 . (Table of Contents) (PDF)

- Gunnar Bender , Lutz Reulecke: Manual of the German lobbyist: How a modern and transparent political management works. Frankfurter Allgemeine Buch , Frankfurt am Main 2004, ISBN 3-89981-005-8 .

- Steffen Dagger (Ed.): Policy advice in Germany: Practice and perspectives. VS-Verlag, Wiesbaden 2004, ISBN 3-531-14464-2 .

- Ulrich Müller, Sven Giegold, Malte Arhelger (Eds.): Guided Democracy? How neoliberal elites influence politics and the public. VSA, 2004, ISBN 3-89965-100-6 .

- Nicola Berg : Public Affairs Management. Gabler, Wiesbaden 2003, ISBN 3-409-12387-3 .

- Manfred Strauch: Lobbying. Economy and politics in interplay. Gabler, Wiesbaden 1993, ISBN 3-409-19183-6 .

Literature with a focus on the European Union

- Klemens Joos: Success through process competence. Paradigm shift in lobbying after the Lisbon Treaty , published in: Doris Dialer; Margarethe Richter (ed.): Lobbying in the European Union: Between professionalization and regulation . Springer VS 2014, ISBN 978-3-658-03220-3 .

- Alexander Classen: Representation of interests in the European Union. On the legality of political influence , Springer VS, Wiesbaden 2014, ISBN 978-3-658-05410-6 .

- Rinus van Schendelen : The Art of EU Lobbying . Successful public affairs management in the labyrinth of Brussels. Lexxion, Der Juristische Verlag, Berlin 2012, ISBN 978-3-86965-194-1 .

- Wolfgang Gründinger : lobbying in climate protection. The influence of interest groups on the national structure of the EU emissions trading . VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, 2012, ISBN 978-3-531-18348-0 .

- Klemens Joos: Lobbying in the new Europe: Successful representation of interests after the Lisbon Treaty. Wiley-VCH Verlag, 2010, ISBN 978-3-527-50564-7 (also published in English: Lobbying in the new Europe: Successful representation of interests after the Treaty of Lisbon. 2011)

- Klemens Joos: Representation of the interests of German companies at the institutions of the European Union. Dissertation at the business administration faculty of the LMU Munich, BWV - Berliner Wissenschafts-Verlag, 1998, ISBN 3-87061-773-X .

- Bernd Hüttemann : European governance and German interests . Democracy, lobbyism and Art. 11 TEU, first conclusions from "EBD Exklusiv", November 16, 2010 in Berlin. In: EU-in-BRIEF . No. 1 , 2011, ISSN 2191-8252 ( online (PDF; 266 kB)).

- Hans-Jörg Schmedes: The mosaic of mediation of interests in the multi-level system of Europe . In: Federal Center for Political Education (Ed.): From Politics and Contemporary History . 19 (lobbying and policy advice). Bonn 2010 ( online ).

- Steffen Dagger, Michael Kambeck (Ed.): Policy advice and lobbying in Brussels. VS-Verlag, Wiesbaden 2007, ISBN 978-3-531-15388-9 .

- Irina Michalowitz: Lobbying in the EU. UTB (paperback) / facultas wuv, Vienna 2007, ISBN 978-3-8252-2898-9 (Europe compact volume 2).

- Claudia Albrecht: The role of the member states for regional integration in the European Union: Analysis of the parameters taking into account interest-driven interaction processes. Dissertation. University of Hamburg, 2008.

- Reiner Eising, Beate Kohler-Koch: Interest politics in Europe. (Governing Europe 8). Nomos, Baden-Baden 2005, ISBN 3-8329-0779-3 .

Case studies

- Carsten Bockstette: Corporate interests, network structures and the emergence of a European defense industry. A case study using the example of the establishment of the European Aeronautic, Defense and Space Company (EADS). Kovač, Hamburg 2003, ISBN 3-8300-0966-6 .

- Steffen Dagger: Energy policy & lobbying: The amendment of the Renewable Energy Sources Act (EEG) 2009. ibidem-Verlag, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-8382-0057-6 .

- David Krahlisch: Lobbyism in Germany - Using the example of the diesel particulate filter. VDM Verlag Dr. Müller, Saarbrücken 2007, ISBN 978-3-8364-2316-8 .

- Diana Wehlau: Lobbyism and Pension Reform. The influence of the financial services industry on the partial privatization of old-age insurance. VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, Wiesbaden 2009, ISBN 978-3-531-16530-1 .

- Hans-Jörg Schmedes: Business and consumer protection associations in the multi-level system. Lobbying activities by British, German and European associations. VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, Wiesbaden 2008, ISBN 978-3-531-15631-6 .

- Johanna Veit: EU lobbying in the field of green genetic engineering: influencing and success factors. Tectum Verlag, 2010, ISBN 978-3-8288-2257-3 .

- Johannes Lahner: Booming commercial lobbying? A comparative study of commercial lobbying in the US and Germany using the automotive industry. Kovač, Hamburg 2013, ISBN 978-3-8300-7406-9 .

- The lobbyists are being investigated . In: Die Welt , March 11, 2005

Web links

Europe / EU

- Excerpt from Europe Inc. In: SWB 01/1998. cbgnetwork.org

- corporateeurope.org Corporate Europe Observatory (CEO), Brussels-based non-governmental organization that aims to demonstrate the “power of lobbying”

- Ruth Reichstein: The real pullers: lobbyists in Brussels . deutschlandfunk.de , Background Economy (Archive) , October 2, 2005

- List of registered stakeholders in the European Parliament's voluntary lobby register. europarl.europa.eu

- lobbycloud.eu (lobby documents put online by politicians that are circulating in the EU bureaucracy)

- Website lobbyfacts.eu (English)

- lobbyingtransparency.org

- Lobbyism - The silent power . (PDF; 2.2 MB) netzwerkrecherche.de

Germany

- “The backers”: lobbies are increasingly influencing politics. Does that endanger democracy? brandeins.de , September 2012

- Lobbyism in Germany . uni-leipzig.de ( abstract from the symposium of the researchjournal New Social Movements in cooperation with the Federal Agency for Civic Education and the Heinrich Böll Foundation , Berlin, January 24-26, 2003)

Austria

- alpac.at ALPAC, Austrian Lobbying and Public Affairs Council

- oepav.at ÖPAV, Austrian Public Affairs Association

Other countries

- sourcewatch.org focus on USA

- spinwatch.org focus on England

Individual evidence

- ↑ lobbying . duden.de

- ↑ lobbying . duden.de

- ↑ lobbying . duden.de

- ↑ Hans-Jürgen Papier : On the tension between lobbyism and parliamentary democracy. (PDF; 102 kB) Lecture on the occasion of the presentation of the book The Fifth Power. Lobbying in Germany on February 24, 2006 in the Berlin Reichstag.

- ^ Peter Lösche : Associations and lobbyism in Germany. Stuttgart 2007, p. 10.

- ^ Thilo Bode: Lobbyism 2.0: The Industrial-Political Complex | Sheets for German and international politics. In: https://www.blaetter.de/ . Blätter Verlagsgesellschaft mbH, 2018, accessed on January 6, 2020 .

- ↑ Carsten Bockstette: Corporate interests, network structures and the emergence of a European defense industry: a case study using the example of the establishment of the "European Aeronautic, Defense and Space Company" (EADS) . Hamburg 2003, ISBN 3-8300-0966-6 , p. 17.

- ^ A b Rinus van Schendelen: Machiavelli in Brussels: The Art of Lobbying the EU . Amsterdam 2002, p. 203 f .

- ↑ a b Rinus van Schendelen: National Public and Private EC Lobbying . Dartmouth 1993, p. 3 .

- ^ Günter Bentele: Lobbying: Conceptual basics and field of activity in Berlin. Konrad Adenauer Foundation, April 8, 2008, accessed June 20, 2020 .

- ↑ Leo Kißler: Political Sociology . UVK Verlagsgesellschaft, Konstanz 2007, ISBN 978-3-8252-2925-2 , p. 130 .

- ^ Scott Ainsworth: Regulating Lobbyists and Interest Group Influence . In: The Journal of Politics . 55th year, no. 1 , January 1993, p. 52 .

- ^ Klaus Schubert / Martina Klein: Das Politiklexikon . 4th edition. Bonn 2006, p. 187 .

- ↑ Stefan Schwaneck: Lobbyism and Transparency: A Comparative Study of a Complex Relationship (= Comparative Political Science ). Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden, Wiesbaden 2019, ISBN 978-3-658-26898-5 , p. 20 , doi : 10.1007 / 978-3-658-26899-2 ( springer.com [accessed June 20, 2020]).

- ↑ Carsten Bockstette: Corporate interests, network structures and the emergence of a European defense industry: a case study using the example of the establishment of the "European Aeronautic, Defense and Space Company" (EADS) . Hamburg 2003, ISBN 3-8300-0966-6 , p. 18.

- ^ Peter Köppl: Power Lobbying: The Practical Handbook of Public Affairs . Vienna 2003, p. 95 .

- ^ Hans Merkle: Lobbying: The practical handbook for companies . Darmstadt 2003, ISBN 3-89678-233-9 , p. 10.

- ↑ Alexander Bilgeri: The phenomenon of lobbyism - a consideration against the background of an expanded strategy-structure discussion . Books on demand, Lindau 2001, ISBN 3-8311-0675-4 , p. 13.

- ↑ Manfred Strauch: Status of the lobby discussion in Europe - a professional right for lobbyists? In: Manfred Strauch (Hrsg.): Lobbying - economy and politics in the interplay . Frankfurt 1993, p. 111 .

- ↑ Iris Wehrmann: Lobbying in Germany - Concept and Trends . In: Ralf Kleinfeld / Annette Zimmer / Ulrich Willems (eds.): Lobbying: Structures. Actors. Strategies. Wiesbaden 2007, p. 39 .

- ^ Clive S Thomas: Research Guide to US and International Interest Groups . Westport 2004, p. 6 .

- ^ Ulrich von Alemann / Florian Eckert: Lobbyism as shadow politics . In: From Politics and Contemporary History . 54th year, no. 15/16 , 2006, pp. 4 .

- ↑ Thomas Leif / Rudolf Speth: The fifth power - Anatomy of lobbyism in Germany . In: Thomas Leif / Rudolf Speth (ed.): The fifth power - lobbyism in Germany . Bonn 2006, p. 12 .

- ^ Bruce C. Wolpe: Lobbying Congress: How the System Works. Washington DC 1990, p. 9 .

- ^ Rune Jørgen Sørensen: Targeting the Lobbying Effort: The Importance of Local Government Lobbying. In: European Journal of Political Research . 34th year, no. 2 , 1998, p. 303 .

- ↑ Stefan Schwaneck: Lobbyism and Transparency: A Comparative Study of a Complex Relationship (= Comparative Political Science ). Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden, Wiesbaden 2019, ISBN 978-3-658-26898-5 , p. 25th f ., doi : 10.1007 / 978-3-658-26899-2 ( springer.com [accessed June 20, 2020]).

- ↑ Speaking time in Westdeutscher Rundfunk ( memento of the original from June 26, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , 5th radio program, on June 5, 2015 with Hans-Martin Tillack

- ↑ a b Article about the New Social Market Economy initiative of the NGO LobbyControl

- ↑ a b Sabine Nehls, Magnus-Sebastian Kutz: Attack of the surreptitious advertisers , Frankfurter Rundschau, January 9, 2007

- ↑ Short study Favors of Favors - Journalism and Corruption (PDF; 2.0 MB); Network research ; 2013

- ↑ Claudia Peter: Citizens' initiatives controlled by industry? Wind / wind energy / wind turbine opponent , BUND -Regionalverein Südlicher Oberrhein

- ↑ Via industry sponsored educational materials ; LobbyControl; 2011

- ↑ BVerfG, judgment of August 17, 1956, Az. 1 BvB 2/51, BVerfGE 5, 85 - KPD ban.

- ↑ Melanie Amann: The spectacular successes of the solar lobby. In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung . January 26, 2010, accessed August 20, 2020.

- ↑ a b c d e Markus Balser, Uwe Ritzer: Through the back door. The Bundestag locks out corporate lobbyists. In fact, there have never been so many professional whisperers. Your power is enormous. Many operate in hiding and do not have to rely on ID cards. In: Süddeutsche Zeitung , February 29, 2016, p. 17.

- ^ Raimund Kamm: Commentary. German emissions rose in 2016 In: klimaretter.info . January 9, 2017, accessed November 11, 2019.

- ↑ a b Thorsten Denkler: This is how the Bundestag protects lobbyists. In: Süddeutsche Zeitung . January 24, 2015, accessed January 24, 2015.

- ↑ Hans-Jörg Schmedes: Dare to be more transparent? To the discussion about a legal lobby register at the German Bundestag . In: Journal for Parliamentary Issues. ( Page no longer available , search in web archives ) Issue 3/2009, pp. 543–560.

- ↑ Bundestag administration, quoted from: Süddeutsche Zeitung , 23./24. September 2017, p. 37.

- ↑ Paid lobbyists in federal ministries: How the government deceives the public. Monitor, December 15, 2006 at: youtu.be/JWDjsZ6eUHM

- ^ Stefan Krempl: Database provides information about lobbyists in ministries. In: heise online . July 27, 2007.

- ↑ Florian Gathmann, Nils Weisensee: List of lobbyists reveals influence in ministries. In: Spiegel Online . July 26, 2007.

- ↑ Answer of the Federal Government to the minor question of the MPs Volker Beck (Cologne), Thea Dückert , Matthias Berninger , other MPs and the parliamentary group BÜNDNIS 90 / DIE GRÜNEN - Drucksache 16/3431. (PDF; 107 kB).

- ↑ Lobbyists in the staff room. In: Zeit Online . May 11, 2011.

- ↑ Ten years of phasing out nuclear power - a milestone as a crucial test. In: Focus Online . June 14, 2000.

- ↑ The shining winners of the nuclear lobby. The lifetime extension for nuclear power plants is a great success for the energy companies. Now other industries want to use this lobbying as an example. In: Zeit Online . September 7, 2010.

- ↑ An analysis of the systematic action of the atomic lobby in the years 2009 to 2011 with extensive source material can be found at: AtomkraftwerkePlag: Influence and campaigns of the atomic lobby. In: atomkraftwerkeplag.wikia.com . Retrieved August 18, 2012.

- ^ "Collegium" and "Adlerkreis" - These are the lobbyists in Berlin's backroom clubs. Retrieved January 14, 2019 .

- ↑ Laura Weigerle: Black-Red sees red. In: The daily newspaper . June 21, 2017.

- ↑ Register of the National Council's vested interests (PDF; 239 KB)

- ↑ Register of vested interests of the Council of States (PDF; 140 kB)

- ↑ a b Olivia Kühni: The powerful whisperers in the Federal Palace . In: Tagesanzeiger . September 15, 2011, accessed May 18, 2015.

- ↑ Thomas Angeli: The coveted "GA for the Federal Palace". In: The Observer. Issue 5, 2008, accessed October 22, 2011.

- ↑ Valerie Zaslawski: Lobbying in the Federal Palace should become more transparent. In: Neue Zürcher Zeitung . January 25, 2018, accessed June 4, 2018 .

- ↑ If you have problems like Alpiq: The 7 Swiss lobbying booths for the rough. In: watson.ch. Retrieved March 21, 2016 .

- ↑ Hans-Jörg Schmedes: Business and consumer protection associations in the multi-level system . VS, Verl. Für Sozialwiss., Wiesbaden 2008, ISBN 978-3-531-15631-6 , p. 371 .

- ↑ Sven Giegold in conversation: “An unbelievable lobby battle”. Interview. In: sueddeutsche.de . June 21, 2010.

- ^ The many seductions for the MPs ( Memento from January 3, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) In: Tiroler Tageszeitung . April 10, 2011.

- ^ Register of Interest Representatives ( Memento of December 23, 2009 in the Internet Archive ), European Commission

- ↑ Transparency Initiative. In: europa.eu . European Commission .

- ↑ EU lobbyism in focus ( Memento from May 29, 2015 in the Internet Archive ), European Parliament

- ^ Heiko Kretschmer, Hans-Jörg Schmedes: Lacking courage and determination. Experience from abroad suggests the EU should make its lobbyists register mandatory , European Voice, 10 September 2009, p. 12.

- ^ Heiko Kretschmer, Hans-Jörg Schmedes: Enhancing Transparency in EU Lobbying? How the European Commission's Lack of Courage and Determination Impedes Substantial Progress. (PDF; 158 kB). In: fes.de/ipg/ . International Politics and Society, 1/2010, pp. 112–122.

- ↑ More transparency in the lobby jungle in Brussels? ( Memento of May 29, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) European Parliament

- ↑ Eva Dombo: EU Commission wants transparency for lobby work: “A good lobbyist must love Europe”. In: tagesschau.de . June 22, 2008.

- ↑ Transparency register for organizations and self-employed individuals involved in the design and implementation of EU policies. In: europa.eu .

- ↑ Guidelines for the financial information for a more detailed explanation of Annex 2 Part B (Financial information) of the interinstitutional agreement on the Transparency Register. In: europa.eu .

- ↑ Code of Conduct. In: europa.eu .

- ↑ “Lobbying” becomes “Transparency”. In: euractiv.de .

- ↑ Christopher Ziedler: Lobbying the EU: The whisperers of Brussels. In: Der Tagesspiegel . July 1, 2014, accessed August 20, 2020.

- ↑ Commission Decision on the publication of information on meetings held between Members of the Commission and organizations or self-employed individuals. (PDF) In: ec.europa.eu . (English).

- ↑ EU Parliament to end secret lobby sessions

- ↑ Text adopted by the EU Parliament on the transparency of lobbying

- ↑ On the problem cf. Bernd Hüttemann : European governance and German interests . Democracy, lobbyism and Art. 11 TEU, first conclusions from "EBD Exklusiv", November 16, 2010 in Berlin. In: EU-in-BRIEF . No. 1 , 2011, ISSN 2191-8252 ( online (PDF; 266 kB) [accessed April 24, 2011]). online ( Memento from April 6, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) p. 5.

- ^ Daniela Weingärtner; Johannes Gernert: Brussels car dealerships . In: the daily newspaper , November 29, 2008.

- ↑ Hackländer, Sabine: A long way for less CO2 emissions , tagesschau.de

- ↑ a b Victory of the car lobby: Federal government prevents stricter emission standards. In: Spiegel Online . October 21, 2013, accessed May 1, 2016 .

- ↑ Bankers determine EU policy. In: taz.de . May 5, 2010.

- ^ The powerless in the European Parliament. In: tagesspiegel.de , July 17, 2010.

- ↑ Finance Watch: Interest group as a counterpoint to the finance lobby. In: faz.net . April 12, 2011.

- ↑ European Union: Commissioner Dalli resigns over corruption affair. In: spiegel.de . October 16, 2012.

- ↑ Michel Petite. In: Lobbypedia.de . December 2013.

- ↑ Again undercover opinion- making - today: Biosprit lobbycontrol.de, July 10, 2009.

- ↑ Peter Nowak : Greenwashing for biofuels revealed. For months, the biofuel industry tried to influence public opinion on its own behalf with PR campaigns. In: Telepolis online . “Energy & Climate News” section, July 14, 2009.

- ↑ a b Lena Kampf, Robert Roßmann: Schmidt's single-handed glyphosate was prepared for a long time. Retrieved January 6, 2020 .

- ↑ Glyphosate: CSU Minister Schmidt made the decision “for himself”. In: The time . November 28, 2017, accessed January 6, 2020 .

- ^ Thilo Bode: Lobbyism 2.0: The Industrial-Political Complex | Sheets for German and international politics. In: https://www.blaetter.de/ . Blätter Verlagsgesellschaft mbH, 2018, accessed on January 6, 2020 .

- ↑ Why the yes to glyphosate is poison for a possible coalition formation. Retrieved January 6, 2020 .

- ↑ Schmidt has to go! In: secure.avaaz.org. Retrieved January 6, 2020 .

- ↑ Glyphosate: Angela Merkel will pay a higher price for a grand coalition. In: manager-magazin.de. Retrieved January 6, 2020 .

- ^ Christiane Grefe: Glyphosate: A German Triumph? Not really. In: The time . November 28, 2017, accessed January 6, 2020 .

- ↑ Hannelore Crolly: Yes to glyphosate: Schmidt's solo effort comes in very handy for the EU Commission. In: The world . November 28, 2017, accessed January 6, 2020 .

- ↑ Controversial herbicide: Monsanto is said to have bought studies on glyphosate. In: Spiegel Online . December 5, 2019, accessed January 6, 2020 .

- ↑ Also in Germany: Industry co-finances glyphosate studies. In: tagesschau.de . Retrieved January 6, 2020 .

- ↑ Ulrich von Alemann (ed.): Organized interests in the Federal Republic . Leske + Budrich 1987, ISBN 3-8100-0617-3 , p. 71.

- ↑ lobbycontrol.de (PDF)

- ↑ aquafed.org

- ↑ eslnetwork.com

- ↑ ecipe.org

- ↑ interelgroup.com ( Memento from March 25, 2016 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ edelman.be

- ↑ apcoworldwide.com

- ↑ Bernhard Weßels (Ed.): Associations and Democracy in Germany . Opladen 2001, p. 11 f .

- ^ Peter Lösche: Associations in the Federal Republic of Germany - An introduction. W. Kohlhammer Verlag, 2007, p. 9 .

- ↑ Rudolf Speth (Ed.): The fifth power - lobbyism in Germany. VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, 2007, p. 16 .

- ↑ Association statistics 2011. (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on December 14, 2012 ; Retrieved April 12, 2013 .

- ^ The ADAC check . ( Memento from January 12, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) WDR, first broadcast on January 14, 2013, 3 p.m.