Lisbon Treaty

The Treaty of Lisbon (originally also called the EU Basic Treaty or Reform Treaty , Portuguese Tratado de Lisboa ) is a treaty under international law between the 27 member states of the European Union .

The Treaty of Lisbon on 13 December 2007 under the Portuguese Presidency in Lisbon signed and entered into force on 1 December 2009.

The Lisbon Treaty reformed the Treaty on European Union (EU Treaty) and the Treaty establishing the European Community (EC Treaty), which was renamed the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (AEU Treaty); Furthermore, Protocol No. 2 amended the Euratom Treaty (see Article 4 (2)).

The full title of the treaty is "Treaty of Lisbon amending the Treaty on European Union and the Treaty establishing the European Community", published in OJ. 2007 / C 306/01, last published by printing the consolidated text versions in OJ. 2012 / C 326/01.

In terms of content, the Lisbon Treaty adopted the essential elements of the EU Constitutional Treaty , which was rejected in a referendum in France and the Netherlands in 2005 . In contrast to the Constitutional Treaty, however, it did not replace the EU and EC Treaties, it only changed them.

The innovations of the Lisbon Treaty included the legal merger of the European Union and the European Community , the extension of the co-decision procedure to police and judicial cooperation in criminal matters , the greater involvement of national parliaments in EU law-making , and the introduction of a European citizens' initiative , the new office of the President of the European Council , the expansion of the powers of the EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy , the establishment of a European External Action Service , the legally binding nature of the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights and the first-time regulation of an exit from the EU. Before the Lisbon Treaty, the EU and EC Treaties were most recently amended by the 2003 Treaty of Nice and by the accession of new member states in the meantime. The regulations on EU military operations from the Nice Treaty have been expanded, thus developing the economic alliance into a defense alliance.

In the ratification of the treaty took place in several Member States in difficulties. In particular, a negative referendum in Ireland in summer 2008 delayed the original schedule. After the referendum was repeated in autumn 2009, the contract finally came into force on December 1, 2009.

structure

The concept behind the EU Constitutional Treaty signed in 2004 was to repeal all existing EU treaties (Art. IV-437 TEU) and replace them with a uniform text called the “Constitution”. After the Constitutional Treaty had failed referenda in France and the Netherlands, however, in 2005, this goal was in 2007 granted mandate for the Intergovernmental Conference explicitly given up on the Reform Treaty. Instead, the substance of the constitutional treaty was incorporated into the existing treaty.

The Lisbon Treaty is therefore an "amending treaty", which essentially consists of the changes made to the previous treaties. It is structured as follows:

| I. II. III. IV. V. VI. |

Preamble Amendments to the EU Treaty (Article 1) Amendments to the EC Treaty (Article 2) Final provisions (Articles 3 to 7) Protocols (Article 4) Annex (correspondence tables for continuous renumbering in accordance with Article 5) |

The EU thus continues to be based on several treaties. The most important of these are the Treaty on European Union (TEU) and the Treaty establishing the European Community (EGV), which was renamed the “ Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union ” (TFEU) by the Treaty of Lisbon . This name change came about because, due to the changed structure of the EU, the European Community no longer existed as an institution with its own name; all of its functions have been taken over by the EU.

In addition to the two main contracts, other documents to which the EU treaty refers are part of EU primary law. There are 37 protocols and 2 annexes (cf. Art. 51 EU Treaty) as well as the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights (cf. Art. 6 Paragraph 1 EU Treaty). In addition, according to Article 6, Paragraph 2 of the EU Treaty , the EU is to accede to the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR).

The 65 declarations attached to the final act and the “Explanations on the Charter of Fundamental Rights” are not part of the treaties due to the lack of a special arrangement and therefore do not belong to primary law. Both serve, however, as an aid to interpretation (within the meaning of Article 31, Paragraph 2 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties ) and can be used to support court decisions, for example. The declarations attached to the Treaty of Lisbon clarify the positions of individual or all Member States on certain aspects.

Chronological order

|

Sign in force contract |

1948 1948 Brussels Pact |

1951 1952 Paris |

1954 1955 Paris Treaties |

1957 1958 Rome |

1965 1967 merger agreement |

1986 1987 Single European Act |

1992 1993 Maastricht |

1997 1999 Amsterdam |

2001 2003 Nice |

2007 2009 Lisbon |

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| European Communities | Three pillars of the European Union | ||||||||||||||||||||

| European Atomic Energy Community (EURATOM) | → | ← | |||||||||||||||||||

| European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) | Contract expired in 2002 | European Union (EU) | |||||||||||||||||||

| European Economic Community (EEC) | European Community (EC) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| → | Justice and Home Affairs (JI) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Police and judicial cooperation in criminal matters (PJZS) | ← | ||||||||||||||||||||

| European Political Cooperation (EPC) | → | Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) | ← | ||||||||||||||||||

| Western Union (WU) | Western European Union (WEU) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| dissolved on July 1, 2011 | |||||||||||||||||||||

Changes to the Treaties in the Nice version

The main aim of the Lisbon Treaty (as well as the failed constitutional treaty) was to reform the EU's political system . On the one hand, the internal coordination mechanisms should be expanded and the veto options of individual member states reduced in order to keep the EU capable of acting after the eastward enlargement in 2004 ; on the other hand, the rights of the European Parliament should be strengthened in order to increase the democratic legitimacy of the EU.

Important changes included:

- an expansion of the legislative competences of the European Parliament , which has now been put on an equal footing with the Council of the European Union (also known colloquially as the Council of Ministers) in most policy areas ;

- the expansion of majority decisions in the Council of the European Union and the introduction of a double majority as a voting procedure (but only from 2014) in order to reduce the possibility of a national veto ;

- the new office of President of the European Council , who is appointed for two and a half years by the European Council in order to ensure greater continuity in its activities ( Art. 15 EU Treaty);

- the introduction of an "EU Foreign Minister" (albeit under the name of High Representative for Foreign and Security Policy ), who is appointed by the European Council and at the same time is Chairman of the Council of Foreign Ministers and Vice-President of the Commission ( Art. 18 EU Treaty);

- the creation of a European External Action Service made up of officials from the Commission, the Council Secretariat and the diplomatic services of all Member States;

- the formulation of a competency catalog that defines the competences of the EU more clearly than before;

- the institutionalization of enhanced cooperation , through which a group of member states can achieve further integration steps with one another, even if others do not participate;

- the expansion of the Common Security and Defense Policy (CSDP), including through the expansion of the European Defense Agency and the introduction of a start-up fund for short-term financing of military activities (in which, however, only willing Member States participate);

- the endowment of the EU with its own legal personality (previously reserved for the EC );

- the EU's accession to the European Convention on Human Rights ( Art. 6 EU Treaty);

- the introduction of the European Citizens' Initiative ;

- a tightening of the EU accession criteria ;

- the regulation of the voluntary withdrawal of member states from the EU.

Institutional innovations

European Parliament

The European Parliament is one of the institutions whose competences have been strengthened the most by the Treaty of Lisbon. In accordance with Article 14 of the EU Treaty, it acts as legislator together with the Council of the European Union and exercises budgetary powers together with it . The co-decision procedure , which grants Parliament and the Council equal rights in the legislative process, has become the new “ordinary legislative procedure” and is now valid in the majority of policy areas . In particular, the common agricultural policy and police and judicial cooperation in criminal matters have been included in the remit of Parliament; however, the common foreign and security policy remained the sole competence of the Council.

The European Parliament was also given new powers with regard to the EU budget : the Parliament had already had budgetary rights , from which, however, expenditure on the common agricultural policy was excluded, which made up around 46% of the total budget. With the Treaty of Lisbon, the agricultural sector was now included in the regular budget; Parliament has the final say on all EU spending. The final decision on the EU's revenue will still lie with the Council, so that Parliament will still not be able to independently increase the overall budget or introduce EU taxes.

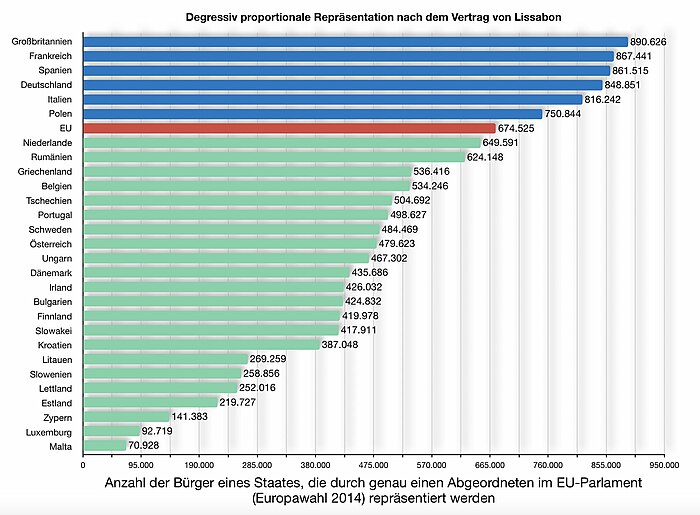

The Treaty left the precise provisions on the composition of the European Parliament to a later decision of the European Council . He merely determined a “ degressively proportional ” representation of the citizens, according to which a large state is entitled to more seats than a small one, but fewer per inhabitant. In addition, each state must have between 6 and 96 seats. The number of MEPs has been set at 750 plus the Speaker of Parliament (instead of 785 after the 2007 enlargement and 736 after the 2009 European elections ).

The voting procedures of the Parliament have not been changed:

- absolute majority of the votes cast: normal case (e.g. legislation, confirmation of the commission president)

- absolute majority of elected members: in the second reading in legislative processes

- Two-thirds majority : for some exceptional decisions (e.g. motion of no confidence against the Commission)

European Council and its President

The European Council , which is composed of the heads of state and government of the individual member states and has met regularly since the 1970s, is considered to be an important engine of European integration . Since the Maastricht Treaty , it has had an essential role in the intergovernmental area of the European Union, but (unlike the Council of Ministers ) it was not an organ of the European Communities. The Treaty of Lisbon formally placed it on an equal footing with the other institutions. He was also given the powers of the “Council made up of Heads of State and Government” named in the EC Treaty , which in fact but not legally agreed with the European Council.

The Treaty of Lisbon did not change the main tasks of the European Council. You are still:

- the definition of the “general political objectives and priorities” of the European Union without the European Council itself becoming legislative;

- fundamental decisions such as new EU enlargements or the transfer of further powers to the EU;

- the right to make nominations for the Commission President , the High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy and the other Commissioners.

The forms of voting in the European Council also remained unchanged: it continues to make decisions “by consensus”, ie unanimously ; the qualified majority only applies to personnel decisions .

However, a major innovation of the Lisbon Treaty was the creation of the office of President of the European Council . This is elected by the European Council with a qualified majority for two and a half years (with one-time re-election) and thus replaces the Council Presidency , which previously rotated every six months and was held by one of the heads of government . This was intended to increase the efficiency of the activities of the European Council: A disadvantage of the earlier system of "semester presidents" was, on the one hand, the changing priorities in the political agenda with the presidency and the different mentality of the presidents; was also head of government of his own country. The full-time president should ensure continuous coordination between the heads of government through the extended term of office. It should also give the European Council - as one of the main decision-making bodies of the EU - a "face". However, he should not intervene in day-to-day politics and ultimately only publicly represent the positions that the heads of state and government would have agreed on beforehand.

Council of the European Union

The Council of the European Union (“Council of Ministers”) consists of the ministers of the individual member states who are responsible for the current topic on which the Council meets. Its main task is to legislate together with the European Parliament . Basically, the Council usually decides unanimously, provided that Parliament has little or no say, and according to the majority principle, provided that Parliament is also involved in the decision-making process.

With the Treaty of Lisbon, the latter variant became the norm, so that the Council usually decides with a qualified majority and a right of veto for individual countries only applies in a few exceptional cases . However, all questions relating to the common foreign and security policy and taxes will continue to be decided unanimously . Another new feature is that the Council of Ministers meets in public for all legislative decisions. This is to improve transparency.

In contrast to the European Council, the principle of a six-monthly rotating Council Presidency between the member states was retained for the Council of Ministers . The EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy , elected for a period of five years, was appointed as permanent chairman only for the newly created Council for Foreign Affairs ( see below ) .

“Double majority” in Council decisions

An important amendment to the treaty concerned the voting arrangements in the Council of Ministers. There, the votes of the individual countries have so far been weighted for the so-called “ qualified majority ” (which is necessary for most substantive decisions). Larger countries generally received more votes, smaller ones fewer; the precise weighting of votes was largely arbitrary in the Treaty of Nice . For a decision, there had to be a majority of (a) at least half of the states, which at the same time represented (b) 62% of the EU population and (c) 74% of the weighted votes (namely 258 out of a total of 345 votes).

The Lisbon Treaty replaced this triple criterion with the principle of the so-called double majority : A decision now has to be approved by (a) 55% of the member states, which (b) represent at least 65% of the EU population.

This change should make it easier for majorities to come about, and the new decision-making system should be easier to understand than the previous one. It also brought about a power shift that increased the influence of the large and the very small states at the expense of the medium-sized ones. This led to opposition in particular from Poland , which set a later date for the introduction of a double majority in the Lisbon Treaty. It therefore only came into force as a voting rule from 2014. On the basis of Declaration No. 7 on the Lisbon Treaty, states in disputes could demand that the weighting of votes from the Nice Treaty be used until 2017. According to the so-called Ioannina clause , a certain minority of states can also continue to demand that a decision be postponed.

High Representative for Foreign and Security Policy

Another innovation of the Lisbon Treaty concerned the common foreign and security policy (CFSP). The previous formation of the Council of Ministers as the Council for General Affairs and External Relations , in which the foreign ministers of the member states met, was divided into a Council for General Affairs and a Council for Foreign Affairs . While the General Affairs Council continues to have a six-monthly presidency between the member states, the EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy presides over the Council of Foreign Ministers .

This post, which had previously existed (under the name of “ High Representative for the Common Foreign and Security Policy ”), was given a major boost by the Lisbon Treaty. In addition to chairing the Council of Foreign Ministers, he also took on the functions of Foreign Commissioner and a Vice-President of the European Commission . This “ double hat ” is intended to enable him to manage the difficult coordination of European foreign policy. While the High Representative was previously only responsible for implementing the decisions of the Council of Ministers, he can now, as President of the Council and Commissioner, take initiatives and make policy proposals on his own. Fundamental foreign policy decisions can still only be made unanimously by the Council.

At the same time, the Treaty of Lisbon repealed the previous amalgamation of the offices of High Representative and Secretary General of the Council .

In addition, the Lisbon Treaty decided to set up a European External Action Service (EEAS), which will report to the High Representative. It is intended to work with the diplomatic services of the Member States, but not to replace them. The new EEAS should be better equipped in terms of personnel and organization than the previously existing delegations of the European Commission . It will be composed of members of these delegations, diplomats from the Member States and staff from the Council Secretariat .

Commission and its President

There have been few changes in the appointment process and the functioning of the European Commission . Your sole right of initiative in EU lawmaking has been strengthened by reducing the exceptional cases in which the Council can also make legislative proposals - particularly in domestic and judicial policy . In addition, the role of the Commission President has been strengthened: he has now expressly been given directive authority in the Commission and can also independently dismiss individual commissioners ( Article 17 (6) of the EU Treaty).

The wording of the treaty ( Art. 17 (5) EU Treaty) also provided for a downsizing of the commission, so that from 2014 only two thirds of the states should be able to appoint a commissioner unless the European Council unanimously decides otherwise. However, the heads of state and government of the EU decided as early as 2008 not to allow this regulation to come into force for the time being, so that each state continues to provide a commissioner.

As before, the Commission's election process is two-stage: After the European elections , the European Council proposes a candidate for the office of Commission President who must be confirmed by the European Parliament. Since the Treaty of Lisbon, the European Council has had to "take into account" the result of the European elections, i.e. normally propose a member of the European party that has the strongest political group in the European Parliament . The European Council, together with the President of the Commission, then proposes the other Commissioners (including the High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy ), who then have to be confirmed as a college by Parliament. The Commissioners' portfolios are ultimately determined by the President of the Commission, with the exception of foreign policy, which always goes to the High Representative.

National Parliaments

Already in the Maastricht Treaty , the principles of were for the EU subsidiarity and proportionality laid down in the Treaty of Lisbon ( Art. 5 were confirmed EU Treaty). Subsidiarity means that the Union will only take action if “the objectives [...] can not be sufficiently achieved by the Member States either at central, regional or local level, but [...] can be better achieved at Union level”. The Union can only take on a task from the member states if the lower political levels (in the case of Germany the municipalities , federal states and the federal government ) are not able to carry them out sufficiently, but the EU is. The European Court of Justice (ECJ) decides what “sufficient” means in individual cases .

In order to ensure subsidiarity, the Treaty of Lisbon strengthened the rights of national parliaments in particular through a so-called early warning system : within eight weeks of the Commission launching a legislative proposal, they can now explain why they believe this law is against offends the idea of subsidiarity. In the event of criticism from a third of the parliaments, the Commission must review its proposal. It can also reject the objection of the parliaments, but must justify its decision in any case.

Ultimately, the European Court of Justice (ECJ) remained responsible for upholding the subsidiarity principle . As before, the governments of the Member States and the Committee of the Regions can take legal action here.

Dissolution of the three-pillar model and legal personality of the EU

According to the previous treaty, the political system of the EU was based on so-called " three pillars " ( Art. 1 Para. 3 Clause 1 EU):

- the European Communities ( Euratom and European Community ),

- the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) and

- of police and judicial cooperation in criminal matters (PJC).

Only the European Communities, but not the European Union itself, had legal personality . This meant that the EC was able to make generally binding decisions within the scope of its powers, while the EU only acted as an " umbrella organization ". In the CFSP in particular, the EU could not appear as an independent institution, but only in the form of its individual member states.

The Lisbon Treaty dissolved the "three pillars" by replacing the words "European Community" with "European Union" throughout (the previous Treaty establishing the European Community became the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union ). The EU thus took on the legal personality of the EC. In this way, as a subject of international law, it can in its own name (albeit in principle only by unanimous decision of the Council for Foreign Affairs )

- sign international treaties and agreements,

- maintain diplomatic relations with other countries through the newly created European External Action Service and

- Become a member of international organizations , provided they also accept non-national members (e.g. the Council of Europe ).

The European Atomic Energy Community (Euratom), which belonged to the European Communities alongside the EC , continued to exist as an independent organization after the Treaty of Lisbon. However, it is affiliated with the EU in its structures and shares its organs with the EU.

Content innovations

In addition to the institutional changes, the Lisbon Treaty also provided for a number of substantive innovations that, for example, reorganized the competences of the European Union or restructured certain forms of cooperation between the member states. Here, too, the treaty was essentially based on the failed EU constitutional treaty .

Delimitation of competencies

According to the “ principle of limited individual authorization”, the European Union basically only has the powers that are expressly granted to it in the founding treaties. In the earlier contracts, however, these competencies were not listed in a specific article, but distributed over the entire contract. This made it difficult to understand the treaty and often led to confusion about the extent of the Union's powers.

In the Lisbon Treaty, this problem was to be resolved by a “competency catalog” (based on the example of the competency catalog in the German Basic Law ), which presents the Union's competences more systematically. Art. 2 TFEU therefore distinguishes between exclusive, shared and supporting competences. Articles 3 to 6 of the TFEU finally assign the various policy areas in which the EU has competences to the respective type of competence.

- In the case of exclusive competences (Art. 3 Para. 1 lit. a – e, Para. 2 TFEU) of the Union, only the EU is responsible. These include in particular trade policy and the customs union .

- In the case of shared competences (Art. 4 TFEU), the EU is responsible, but the member states can enact laws if the Union does not do so itself. This includes the areas of the internal market , agricultural policy , energy policy , transport policy , environmental policy and consumer protection .

- In the case of supporting responsibility (Art. 6 TFEU), the EU can support, coordinate or supplement measures of the member states, but cannot itself legislate. This applies, among other things, in the areas of health policy , industrial policy , education policy and disaster control .

In addition, the intergovernmental areas of economic and employment policy are mentioned in the text of the treaty (Art. 5 TFEU) and foreign and security policy in Art. 21 to 46 TEU , in which the EU can set guidelines, but only by unanimous decision of the member states in the Council of Ministers .

Goals and values of the Union

The “goals and values of the Union”, which are binding for all EU action, were also expressly defined in the Lisbon Treaty. So it says in Art. 2 EU-Treaty:

“The values on which the Union is founded are respect for human dignity , freedom , democracy , equality , the rule of law and respect for human rights, including the rights of persons belonging to minorities . These values are common to all member states in a society that is characterized by pluralism , non-discrimination , tolerance , justice , solidarity and equality between women and men . "

Article 3 of the EU Treaty defines the Union's objectives, including the promotion of peace , the creation of an internal market with free and undistorted competition , economic growth , price stability , a social market economy , environmental protection , social justice , cultural diversity, and worldwide eradication of poverty , Promotion of international law etc.

Charter of Fundamental Rights and accession to the European Convention on Human Rights

An important innovation was the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union , which only became legally binding after the Treaty of Lisbon ( Art. 6 (1) EU Treaty). It binds the European Union and all member states in the implementation of European law .

The Charter had already been adopted and solemnly proclaimed by the European Council in Nice in 2000 , but initially remained without legally binding force. In terms of content, it is based on the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR). In some parts it goes further, in others less far than comparable catalogs of fundamental rights, for example in the German Basic Law. Art. 53 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights expressly stipulates the “ favourability principle ”, according to which the Charter of Fundamental Rights must in no case mean a deterioration in the fundamental rights situation for the individual. If the Charter of Fundamental Rights and other legally valid catalogs of fundamental rights contradict each other, the better regulation for the individual applies.

In the negotiations on the Lisbon Treaty, Poland and Great Britain insisted on so-called opt-out clauses, which mean that the Charter of Fundamental Rights is not applicable in these countries. In 2009 it was added in an additional protocol that this opt-out should also apply to the Czech Republic . This additional protocol should be ratified with the next treaty reform (probably with the next EU enlargement). However, these plans were rejected after the change of government in 2013.

Article 6 (2) of the new EU treaty also provides for the EU's accession to the ECHR. This accession has been under discussion for decades, not least because since the Birkelbach Report of 1961the EU has beenreferringto the principles of the Council of Europe , which are set out in the ECHR,when defining its political values. The EU acquired the legal personality required to join the ECHR through the Treaty of Lisbon ( see above ).

In addition, an amendment to the convention itself was necessary for the EU's accession to the ECHR, as it was previously only open to member states of the Council of Europe ( Art. 59 (1) ECHR). This adjustment was made through the 14th additional protocol to the ECHR, which came into force on June 1, 2010. Finally, an accession agreement has to be negotiated for the intended accession of the EU to the ECHR. This would be a separate international treaty and would therefore have to be decided unanimously by the Council of the EU and ratified by all member states of the ECHR. Ultimately, even after the Lisbon Treaty has come into force, every member state has a veto against the EU's accession to the ECHR, since every member state could reject the specific conditions of this accession.

However, the following explanations on Article 2 (right to life) of the Charter of Fundamental Rights, which are part of the Lisbon Treaty according to Article 52 (3) of the Charter, are of particular importance:

Explanations on Article 2, Paragraph 2 of the European Convention on Human Rights:

“Killing will not be considered a violation of this article if it is caused by the use of force strictly necessary to:

a) defend someone against unlawful violence;

b) to lawfully arrest anyone or prevent someone who is lawfully deprived of liberty from escaping;

c) lawfully put down a riot or insurrection "

Explanations to Article 2 of Protocol No. 6 to the European Convention on Human Rights:

“A state can provide in its law the death penalty for acts committed in times of war or when there is immediate danger of war; this penalty may only be applied in cases provided for by the law and in accordance with its provisions [...]. "

Climate change and energy solidarity

Compared to the Nice Treaty (as well as the Constitutional Treaty), the fight against climate change and energy solidarity have been included as new competencies of the EU.

Common security and defense policy

The area of European security and defense policy, which was renamed Common Security and Defense Policy (CSDP) ( Art. 42 to Art. 46 EU Treaty), was also expanded. It sets the goal of a common defense policy, which, however, can only come into force after a unanimous decision by the European Council. The common security and defense policy should respect the neutrality of certain member states and be compatible with NATO membership of other member states.

By . Article 42 . Paragraph 7 of the EU Treaty, the EU was the first time the character of a defensive alliance ; that is, in the event of an armed attack on one of the member states, the others must provide it with "all the help and assistance in their power". The formulation of this provision goes beyond the mutual obligation of the NATO member states from Article 5 of the North Atlantic Treaty , which only obliges to provide assistance to the extent of the measures deemed necessary.

The EU took over tasks that were previously reserved for the Western European Union (WEU); this was dissolved in mid-2011. In addition, the Lisbon Treaty decided to found a European Defense Agency to coordinate the armaments policy of the member states. The aim is to use armaments expenditure more efficiently and to prevent the Member States from building up unnecessary multiple capacities.

Even after the Treaty of Lisbon, decisions in the area of CSDP can in principle only be made unanimously. Even with the newly introduced passerelle regulation , the CSDP cannot be transferred to the area of majority decisions. However, if a group of member states in the CSDP wants to advance faster than others, they will in future have the option of permanent structured cooperation ( Article 46 of the EU Treaty), which essentially corresponds to enhanced cooperation in other policy fields.

Increased cooperation

The enhanced cooperation , which already existed before, was regulated in more detail by the Treaty of Lisbon in Art. 20 EU Treaty and Art. 326 to Art. 334 TFEU. This includes steps towards integration between a group of EU members if the project cannot be implemented in the entire EU. If at least nine member states are involved, the EU institutions can then set European law, although this only applies in the participating member states. The enhanced cooperation therefore allows for a gradual integration .

The Schengen Agreement and the European Economic and Monetary Union , through which individual member states have already carried out integration steps faster than other steps in the past, served as models for enhanced cooperation . As a new special form, permanent structured cooperation was introduced within the framework of the common security and defense policy .

Contract amendment procedure and passerelle clause

Another important new regulation concerned the way in which further changes to the EU Treaty can be made ( Art. 48 EU Treaty). Previously, any reform of the EU Treaty was provided by a government conference that an amending treaty worked out, which are then ratified in all member states had to. According to the Lisbon Treaty, however, treaty amendments are to be made in the "ordinary amendment procedure" according to the so-called convention method , which was used for the first time to prepare for the failed EU constitutional treaty : The European Council sets up a European Convention for this purpose , made up of representatives of national parliaments and governments, of the European Parliament and the European Commission. This Convention drawn up by consensus a reform proposal before then as before an intergovernmental conference drafted the amendment agreement, which must then be ratified by all Member States. The establishment of a convention can only be dispensed with if the European Council and the European Parliament are of the opinion that the treaty amendment is only minor.

In addition, a "simplified amendment procedure" has been introduced: amendments to Part Three of the TFEU , which includes EU policy areas other than the common foreign and security policy , can therefore be made by unanimous decision in the European Council, even without the need for a formal amendment contract is. However, this decision must not include any expansion of EU competences and must - depending on the provisions in the accompanying national laws - be ratified by the national parliaments if necessary.

Another new feature was the so-called passerelle regulation , according to which, in cases in which the Council of the EU actually takes decisions unanimously, the European Council can determine by unanimous decision that the Council will take decisions with a qualified majority in future. In the same way, it can extend the ordinary legislative procedure to policy areas where it did not apply before. However, if even a single national parliament contradicts this plan, the passerelle regulation cannot be applied. The common security and defense policy is fundamentally excluded from it.

European citizens' initiative

As a new direct democratic element, the Treaty of Lisbon introduced the possibility of a so-called European citizens' initiative ( Article 11 (4) of the EU Treaty). This should enable the European Commission to be asked to submit a draft law on a specific topic. The requirement is one million signatures from a quarter of the EU countries. In the case of a citizens' initiative, too, the Commission may only act within the limits of its powers; an expansion of the EU's competences in this way is therefore ruled out. In December 2010, the European Parliament passed a regulation that contains the precise conditions for the establishment of a European citizens' initiative.

accession

The demand for stricter accession criteria was met. In future, a state wishing to join must respect the values of the EU (ie democracy, human rights, rule of law, etc.) and “work to promote them” ( Art. 49 EU Treaty). According to the version of the Treaty of Nice , on the other hand, “any European state that respects the […] principles [of the EU]” could apply for membership; it did not include an express commitment to promote values.

exit

For the first time, Article 50 of the EU Treaty regulates the withdrawal of a state from the Union, thereby ending the long-standing uncertainty about the existence or non-existence of an (unwritten) right to withdraw. According to this new basic rule, each member state can, in accordance with its constitutional requirements, decide to leave the Union (Art. 50 (1)).

The decision to withdraw must be communicated to the European Council . The Union then negotiates an agreement with this state on the details of the withdrawal and concludes the agreement (Art. 50 (2)). The detailed conditions, in particular the future legal relationship (e.g. association relationship or partnership within the meaning of the European Neighborhood Policy) could be determined in it. According to Art. 50 Para. 4, the representatives of the exiting state do not take part in the deliberations and decisions of the Union bodies on the exit. From the day the Withdrawal Agreement comes into force, the state no longer belongs to the EU.

If two years after a state's declaration of withdrawal to the European Council there is still no withdrawal agreement, for whatever reasons, the withdrawal will take effect immediately in accordance with Art. 50 (3) even without such an agreement , unless the European Council decides in Unanimously agreed with the Member State concerned to extend this period. This provision ensured that an exit would not be unduly prolonged.

With regard to Brexit , the German constitutional lawyer and former judge of the Federal Constitutional Court Udo di Fabio commented on two politically relevant aspects in the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung :

- The Lisbon Treaty does not forbid an exiting state from withdrawing the application for exit within the two-year negotiation period, because the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties (Art. 56, Paragraph 2) prescribes an upstream notification procedure, a kind of notice period. “Before an international treaty that has been concluded without a notice of termination can be effectively terminated [as in the case of the Lisbon Treaty], the intention must be communicated 12 months in advance: the principle of maintaining existing treaties and international organizations exists. In this light everything speaks in favor of the fact that the declaration of the intention to leave the Union would not itself be a termination. "

- Separate negotiations between the EU institutions and EU-friendly regions (London, Scotland, Northern Ireland or Gibraltar) would be a violation of the Lisbon Treaty, according to which the integrity of a member state is expressly protected (Art. 4 (2)).

Changes to the Constitutional Treaty

While the Treaty of Lisbon implemented most of the innovations in the Constitutional Treaty, it also deviated from it on a number of points. This mainly concerned questions of the contract structure and symbol policy.

Retention of the previous contract structure

While the Constitutional Treaty was supposed to repeal all previous treaties and replace them with a single text, the Lisbon Treaty retained the traditional structure of several mutually referring treaties. There is still an EU treaty, which sets out the basic principles of the EU, and a more specific treaty, which details the functioning of its institutions and the content of the supranational policy areas. This more specific treaty, previously the EC Treaty , has now been renamed the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU).

The Euratom Treaty continues to exist after the Treaty of Lisbon as an independent Community Treaty including 6 separate protocols. Changes are set out in Article 4, Paragraph 2 ("Protocol No. 2 attached to this Treaty contains the amendments to the Treaty establishing the European Atomic Energy Community") of the Lisbon Treaty.

State-typical symbols

In contrast to the constitutional treaty, the Lisbon treaty dispensed with typical state symbols such as the European flag , European anthem and Europe day . This symbolic change was intended to dispel fears ( widespread in the United Kingdom , for example ) that the EU should become a new “superstate” through the constitution. In practice, however, nothing changed in the use of the symbols, as these had also been used before without an express contractual basis for this.

In Declaration No. 52 on the Intergovernmental Conference, which is annexed to the Lisbon Treaty as an official document but has no direct legal effect, a majority of the EU states (including Germany and Austria ) also declared that the symbols “will continue to be used for them in the future [...] to express the togetherness of the people in the European Union and their solidarity with it ”.

Designations

Similar to the symbols typical of the state, the designations typical of the state that were provided for in the constitutional treaty were also withdrawn. Instead, the names that already existed in the previous EU treaty were mostly retained.

In particular, the term “constitution” was completely omitted and the founding documents of the EU continued to be referred to as treaties . The "Foreign Minister of the Union" provided for by the constitution has now been renamed the High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy . Its title is reminiscent of the post of “High Representative for the Common Foreign and Security Policy”, which already existed after the Treaty of Nice; however, his powers correspond to those of the foreign minister provided for by the constitution.

Finally, the legal acts passed by the EU also retained the names that were previously valid. Instead of “European laws”, the EU continues to issue regulations , instead of “European framework laws”, directives .

Charter of Fundamental Rights

The Charter of Fundamental Rights , the text of which was adopted verbatim in the Constitutional Treaty, was not incorporated directly into the EU Treaty after the Lisbon Treaty. It was only declared legally binding through a reference in Article 6 (1) of the EU Treaty. This change also had no legal significance and was primarily aimed at removing the external resemblance of the treaty to national constitutions, which mostly also contain catalogs of fundamental rights.

Postponement of the innovations in the voting procedure

Another change in content related to the point in time at which the new rules on qualified majority in the Council of the EU apply. Instead of 2009, as provided by the constitution, the double majority model only came into effect from 2014. Until then, the proportion of votes laid down in the Treaty of Nice remained for majority decisions in the Council . This was mainly due to demands from Poland , for whom the Treaty of Nice was significantly more favorable.

From November 1, 2014 to the end of March 2017, the double majority voting rules already applied . During this period, however, any member of the Council could request that the voting rules of the Treaty of Nice continue to be applied. The new voting procedure did not apply unreservedly until 2017.

It was also agreed that the so-called compromise of Ioannina would continue to apply as an extended protection of minorities . Accordingly, the negotiations in the Council were continued for a “reasonable period” if so requested by at least 33.75% of the Member States or at least 26.25% of the population represented. Since April 1, 2017, the Ioannina compromise has already been applied to simplify matters when at least 24.75% of the member states or at least 19.25% of the population represented demand that negotiations be continued in the Council.

No reduction in commission

Originally, the Treaty of Lisbon, like the Constitutional Treaty, envisaged a downsizing of the European Commission , in which in future each country would no longer have its own commissioner. However, this measure met with criticism, especially in some smaller countries, and was considered one of the reasons why the first referendum held in Ireland on the treaty failed ( see below ) . The European Council therefore decided in December 2008 not to allow the downsizing of the Commission to enter into force.

Creation and ratification of the Lisbon Treaty

Elaboration of the contract

The main features of the Lisbon Treaty were decided by the European Council during the German Council Presidency at the EU summit on June 21 and 22, 2007 in Brussels . The European Council put them down in the mandate to the Intergovernmental Conference, which then worked out the definitive text of the treaty.

As part of the Intergovernmental Conference, which began its work on July 23, 2007, a draft was drawn up comprising 145 pages of the text of the treaty as well as 132 pages with 12 minutes and 51 declarations. At the EU summit in Lisbon on October 18 and 19, 2007, the heads of state and government finally agreed on the final text of the treaty, once again taking changes made by the representatives of Italy and Poland into account. On December 13, 2007, the contract was signed in Lisbon.

On February 20, 2008, the European Parliament voted in favor of the treaty. However, it was only a symbolic decision, because the European Union, of which the European Parliament is an organ, was not itself one of the contracting parties and therefore did not itself take part in the treaty amendment procedure. Only the national organs provided for by the constitutions of the member states were decisive for the ratification process.

Ratification process

General

According to Art. 6 of the Treaty of Lisbon, this should have entered into force on January 1st, 2009, provided that by then all ratifications had been deposited with the government of the Italian Republic. As an alternative, it envisaged entry into force on the first day of the month following the deposit of the last instrument of ratification.

The structure of the Lisbon Treaty, leaving the existing treaties in place and incorporating the largely unchanged substance of the EU Constitutional Treaty into them, should remove the basis for the demand for national referendums and thereby facilitate ratification. Shortly after the EU summit, however, a number of member states called for a referendum, in some cases even by government parties. It was therefore already questionable at this point in time whether the contract would be able to enter into force according to the planned schedule before the European elections in June 2009 . After all, a referendum was only called in Ireland . This took place on June 12, 2008 and led to the rejection of the Reform Treaty. Subsequently, after renegotiations between Ireland and the other EU member states, a second referendum was scheduled for October 2, 2009, which was ultimately successful. In the other Member States, the parliaments voted on the treaty, although there were delays in some cases due to constitutional complaints or political obstacles.

Procedure in individual Member States

The Hungarian Parliament was the first to vote on the Treaty of Lisbon on December 17, 2007 and accepted it with 325 votes in favor, 5 against and 14 abstentions. On January 29th, 2008, the parliaments of Malta followed unanimously and of Slovenia with 74 in favor, 6 against and 10 abstentions. In Romania , Parliament voted in favor of the treaty on February 4, 2008 by 387 votes in favor, one against and one abstention. With the deposit of the ratification instrument on March 11, 2008, the Treaty of Lisbon became the first that Romania ratified as an EU member.

In France , where the constitutional treaty failed after a referendum, the Lisbon Treaty was ratified on February 14, 2008. On January 30, 2008, 210 Senate members had initially voted with 48 votes against and 62 abstentions for an amendment to the French constitution, which would allow the ratification of the Treaty of Lisbon in Parliament without holding a referendum. On February 6, the National Assembly then rejected, by 227 votes to 175, a proposal by the Parti socialiste to hold another referendum on the treaty. The next day the National Assembly then adopted the treaty by 336 votes to 52, with 22 abstentions; at the same time, the Senate ratified by 265 votes to 42 with 13 abstentions. On February 14th, the instrument of ratification signed by President Sarkozy was deposited in Italy.

In the Netherlands , the Second Chamber on June 5th and the First Chamber of Parliament on July 8th, 2008 approved the treaty. On March 21, 2008 , the Bulgarian Parliament was the sixth parliament to accept the Lisbon Treaty with 195 votes in favor against 15 against, in particular from the opposition nationalist party Ataka , and 30 abstentions.

In Poland , following a compromise between the government of Donald Tusk and President Lech Kaczyński , the Sejm voted in favor of the treaty on April 1, 2008 with 384 for, 56 against and 12 abstentions. On April 2, 2008, the Senate passed the treaty by 74 votes to 17 with six abstentions. According to the compromise, the government should not be allowed to approve any changes to the Lisbon Treaty in the future, which affect the Ioannina formula or the Polish opt-out clause for the Charter of Fundamental Rights , without having been authorized by Parliament and the President. The ratification was delayed, however, because President Lech Kaczyński initially signed the law accompanying the treaty on April 10, but not the ratification document itself. At the beginning of June, after the failed referendum in Ireland, he declared the Lisbon Treaty to be irrelevant and announced not to sign the ratification document. Later, however, he gave in and declared that he was ready to ratify the treaty provided that all other EU states ratified it. One week after the positive outcome of the second Irish referendum, he finally signed the ratification document on October 10, 2009. On October 12, it was deposited with the Italian government, thus completing the ratification process.

As in Poland, the Slovak parliament voted on April 10, 2008 after ongoing debates about a national media law, which has long been opposed to ratification due to opposition, with 103 votes to 5 against 41 absent MPs. Portugal ratified the treaty on April 23, 2008 with 208 votes in favor against 21 against, drawn from three left-wing parties, Partido Ecologista Os Verdes , Bloco de Esquerda and Partido Comunista Português . On April 24, 2008 Denmark approved the treaty by 90 votes to 25 with no abstentions.

As in hardly any other EU country, the ratification in Austria was accompanied by violent protests and calls for a referendum. In particular, the Kronen Zeitung , the largest Austrian tabloid , took a sharp position against the treaty and campaigned for a referendum. The background to the rejection was, among other things, Austria's neutrality , which some critics saw endangered by the Treaty of Lisbon. Another point of criticism - especially from the left - was that, according to the Treaty, Euratom should remain an integral part of the EU, i.e. the EU does not plan to phase out nuclear energy across Europe . In spite of this, the National Council voted for the treaty on April 9, 2008 with 151 votes in favor against 27 against; the Federal Council followed on April 24th. Four days later, Federal President Heinz Fischer also signed . After completion of the ratification process, the party leaders of the SPÖ , Alfred Gusenbauer and Werner Faymann , announced in June 2008 that they would hold referendums on future EU treaty reforms. This led to the break of the coalition with the ÖVP and the end of the Gusenbauer government . The new SPÖ-ÖVP government Faymann agreed in the coalition agreement at the end of 2008 to support future Europe-wide referendums on treaty reforms; national referendums should only take place with the consent of both governing parties.

In the United Kingdom , on March 5, 2008, after ongoing debates, a referendum on the EU Reform Treaty, requested by the conservative opposition, was rejected by MEPs in the House of Commons by 311 votes to 248. On March 11, 2008, the House of Commons passed the treaty with 346 votes to 206. A lawsuit to hold a referendum was rejected by the Supreme Court .

In Belgium , the Senate passed the treaty on March 6, 2008 by 48 votes to 8 with one abstention. On April 10, 2008, the Federation Chamber of Deputies voted 116 to 18 with seven abstentions for the treaty. After the various regional parliaments and communities had given their consent, the Belgian instrument of ratification was deposited in Rome on October 15, 2008.

In Sweden , the treaty was approved by the Reichstag on November 20, 2008 with 243 votes to 39, with 13 abstentions, and twenty days later the Swedish instrument of ratification was deposited in Italy.

Procedure in Germany

In Germany , on February 15, 2008, the Bundesrat passed an opinion on the draft law on the Treaty of Lisbon of December 13, 2007 , which its committee on questions of the European Union had recommended, in accordance with Article 76 of the Basic Law . On April 24, 2008, the Bundestag voted in favor of the contract with 515 votes in favor, 58 against and one abstention.

On May 23, 2008, the Federal Council also ratified the EU Treaty with 66 votes in favor and three abstentions; 15 countries agreed, Berlin abstained due to the efforts of the co-governing party Die Linke . On the same day, the CSU Bundestag member Peter Gauweiler , who had already sued the European Constitutional Treaty in 2005, filed an individual and an organ charge against the treaty with the Federal Constitutional Court . The application was initially submitted by the constitutional law professor Karl Albrecht Schachtschneider ; The expert opinion supporting the lawsuits in the matter comes from the pen of constitutional lawyer Dietrich Murswiek from Freiburg, who subsequently took over the legal representation and represented the lawsuit in the oral hearing before the Federal Constitutional Court. The left parliamentary group , the ecological-democratic party (ödp) under its chairman Klaus Buchner and other individual members of parliament also filed constitutional complaints.

The Office of the Federal President announced on June 30th that Horst Köhler would not sign the ratification document before the judgment was pronounced at the informal request of the Federal Constitutional Court . Köhler therefore limited himself to signing and drawing up the implementation law for the contract on October 8, 2008.

The oral hearing of the lawsuit took place on February 10 and 11, 2009. On June 30, 2009, the Federal Constitutional Court announced its decision . The Lisbon Treaty and the German Consent Act correspond to the requirements of the Basic Law. The German law accompanying the Treaty of Lisbon, however, violates Article 38.1 of the Basic Law in conjunction with Article 23.1 of the Basic Law, as the rights of the German Bundestag and Bundesrat to participate have not been designed to the required extent. European unification must not be achieved in such a way that there is no longer sufficient space in the member states for the political shaping of economic, cultural and social living conditions. This applies in particular to areas that shape the living conditions of citizens, especially their private space, which is protected by basic rights , as well as to political decisions that are particularly dependent on cultural, historical and linguistic preconceptions, and that are part-political and parliamentary organized space of a political public would unfold discursively . For an integration going beyond the Treaty of Lisbon, the Federal Constitutional Court demands a constitutional decision of the people, but also sees this as a possible political option under Art. 146 GG.

On August 18, it became known that the grand coalition and the federal states, with the participation of the opposition, had agreed in roundtables on the new accompanying laws. Accordingly, the Bundestag must approve "fundamental power shifts" at EU level or new responsibilities of the Commission in the future before the Federal Government can approve. The federal states also have further rights of co-determination in the areas of labor law , environmental policy and the EU budget . The total of four laws were adopted by the Bundestag on September 8 with 446 votes in favor, 46 against and 2 abstentions and unanimously by the Federal Council on September 18, so that on October 1 - one day before the Irish referendum - in Strength could kick. Only the parliamentary group “Die Linke” had introduced an alternative draft law.

The involvement of the Bundestag and Bundesrat required by the Federal Constitutional Court is essentially to be ensured by the Integration Responsibility Act. The Lisbon Implementation Act contains changes in particular to the aforementioned Integration Responsibility Act, which were not possible in advance, but only due to an amendment to the Basic Law that came into force together with the Treaty of Lisbon. Thirdly, the law on cooperation between the Federal Government and the German Bundestag in matters relating to the European Union (EUZBBG) is intended to ensure that the Bundestag is informed at an early stage. A fourth law (EUZBLG) is to regulate the cooperation between the federal government and the federal states in matters of the European Union and include a federal-state agreement (EUZBLV) in its annex. In this context, several well-known constitutional law teachers signed the appeal "Against undemocratic haste - for democratic transparency" to implement the Karlsruhe judgment, in which the federal government, the Bundestag and the Bundesrat were asked to involve the public and to pass the amending law only after the election.

On September 23, 2009, the Federal President signed all the necessary laws. Two days later, after the laws were promulgated in the Federal Law Gazette, Köhler prepared the ratification document, and on the same day it was deposited in Rome.

Procedure in Ireland

Ireland was a member state in which, in addition to parliamentary ratification, for constitutional reasons, a referendum on the Treaty of Lisbon was imperative. This took place on June 12, 2008. All the major parties were in favor of agreeing to the contract, but - unlike the opponents of the contract, especially the Libertas platform founded by Declan Ganley - did not campaign too intensely. In the end, 53.4% of voters rejected the Reform Treaty. The turnout was 53.1%. Irish Justice Minister Dermot Ahern called the result a defeat for the Irish government and politics as a whole, as all major Irish parties had pleaded for the adoption of the treaty. Critics accused the government of having, in contrast to the reform opponents, committed too late and too indecisively to vote in favor. The reform opponents' campaign was criticized in part as irrelevant, as it had addressed content that had little or nothing to do with the treaty.

After the Irish voted “No”, there was a lively discussion in European politics about how to proceed with the implementation of the Lisbon Treaty. Regardless of the events in Ireland, the EU states initially agreed to continue the ratification process. Further ratifications took place after the referendum, and in May 2009 all member states of the European Union with the exception of Ireland had completed the parliamentary ratification process.

At the meeting of the European Council on 11/12 In December 2008 it was finally agreed that Ireland would hold a second referendum. At the same time, slight amendments were made to the treaty that should accommodate Ireland: In particular, the European heads of state and government gave in to the Irish demand that each country retain its own commissioner . In addition, an additional protocol should address certain concerns of the Irish people, for example regarding national sovereignty in tax matters, which is not restricted by the treaty. Overall, this approach was similar to that used in the 2001 Treaty of Nice . This was also initially rejected in an Irish referendum in 2001 - with a significantly lower participation than in 2008 - but was accepted in a second vote in 2002.

In September 2008, the European Parliament launched an investigation into the financing of the No campaign after indications of irregularities appeared. Libertas' activities are said to have been financed by a loan from Declan Ganley , the amount of which is contrary to Irish law. In addition, Ganley's activities with the US Department of Defense - with Ganley's company Rivada Networks, which produces military equipment and has business connections - and the CIA have been linked. However, these allegations have been denied by Ganley and John D. Negroponte, US Deputy Secretary of State, and are now under review by the Irish authorities.

The new referendum in Ireland finally took place on October 2, 2009; a merger of the referendum with the 2009 European elections, which had been discussed in the meantime, was discarded. After much criticism of the last campaign strategy, the pro side positioned itself early on in the second referendum. The largest civic movement was Ireland for Europe , with former European Parliament President Pat Cox as campaign director. The Generation Yes project was set up for young voters and also promoted acceptance of the treaty. In addition, the global financial crisis in particular , in which Ireland was hit hard and the country's EU membership was often perceived as an economic lifeline, caused a shift in sentiment in favor of the treaty at the end of 2008. The referendum finally ended with a confirmation of the contract with 67.1% of the vote, the contract was rejected by a majority in only two of 43 constituencies. The turnout was 58%, which is higher than the previous year.

President Mary McAleese signed the constitutional amendment necessary for ratification on October 15, 2009. On October 21 and 22, 2009, the two houses of parliament passed the accompanying laws, and on October 23, 2009 the instrument of ratification was deposited in Rome.

Procedure in the Czech Republic

In the Czech Republic , the ratification process dragged on the longest of all member states. It was interrupted in mid-October 2007 after the Senate, at the instigation of the governing party ODS, referred parts of the contract to the Constitutional Court for review. The oral hearing took place on November 25th and 26th, 2008, and the court ruled that those parts of the contract against which an action had previously been brought were constitutional. The parliamentary ratification could thus be continued.

While a majority for ratification emerged in both chambers of parliament, Czech President Václav Klaus repeatedly spoke out against it; on December 6, 2008 he resigned the honorary chairmanship of the ODS due to the conflicts over the contract. After several postponements, the House of Representatives finally ratified the treaty on February 18, 2009 with 125 votes in favor to 61 against. Again after several delays, the Senate approved the contract on May 6, 2009 with 54 to 20 votes with 5 abstentions. However, Václav Klaus announced that he would only sign the ratification instrument after a successful second referendum in Ireland. This led to harsh criticism from various senators who saw it as a disregard for the Czech parliament. On June 25, Senator Alena Gajdůšková even went so far as to bring up impeachment proceedings against President Klaus for a breach of the constitution.

The ratification process was further delayed on September 1, when several conservative senators filed a complaint with the Constitutional Court against the Czech law accompanying the treaty and then on September 29th against the Lisbon Treaty as a whole. On October 6, 2009, the court dismissed the lawsuit against the accompanying laws. The lawsuit against the contract was heard in a public session on October 27th and was adjourned to November 3rd. In September it became known that the British opposition leader David Cameron had announced in a letter to Klaus that if he were to win the general election in May 2010 in the UK, he would hold a referendum on the treaty if Klaus finally ratified it until then.

Despite the successful referendum in Ireland, Klaus did not want to sign the ratification document for the time being. First of all, the President would have to meet new additional demands, including a guarantee that the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights would not allow the Beneš decrees to be breached. The Czech government as well as the governments of other EU member states criticized Klaus' additional demands, but at the EU summit on October 29, 2009, the heads of state and government accepted his ratification conditions.

The Czech Republic is guaranteed with an addition in the treaty that the Charter of Fundamental Rights does not lead to recourse claims by Sudeten Germans and Hungarians expropriated after the Second World War . On November 3, 2009, the Czech Constitutional Court ruled that the Lisbon Treaty was not unconstitutional. On the same day, Klaus signed the ratification document. It was the last to be deposited in Rome on November 13, 2009. The Lisbon Treaty thus entered into force on December 1, 2009 in accordance with Article 6 (2).

Debate and criticism

As with the planned constitutional treaty, the pan-European debate on the Lisbon Treaty was weak. A certain fatigue as well as the lack of publicity due to the ratification in the national parliaments with mostly large, cross-party majorities may have contributed to this. Nevertheless, critics of the treaty drew attention to themselves through public actions in several countries. In Austria, for example, demonstrations for a referendum on the EU reform treaty took place in March and April 2008, organized by the citizens' initiative "Save Austria", the platforms "No to the EU treaty" and "Volxabimmen.at" and the opposition party FPÖ . The various organizations collected around a hundred thousand signatures and handed them over to the Austrian Parliament President Barbara Prammer .

An intense debate on the treaty took place on the occasion of the referendum on June 12, 2008 in Ireland . Here the critics of the contract started an online petition to influence the Irish people in their favor. Conversely, the supporters of the treaty, such as the Young European Federalists , also carried out public actions to win approval for a yes in the referendum.

Resumption of criticism of the constitutional treaty

Since the Lisbon Treaty adopted the substance of the EU Constitutional Treaty almost unchanged, the critics maintained the criticism already expressed about the Constitutional Treaty, also of the Lisbon Treaty. Also Valery Giscard d'Estaing said that the Treaty of Lisbon distinguished only "cosmetic" changes and merely different performing the contents of the EU Constitutional Treaty, to make this "easier to digest" and avoid new referenda. The former President of the Constitutional Convention particularly criticized the omission of the EU flag and the anthem from the new treaty text. In addition, the treaty in its new form is more complex and more difficult to understand than the draft constitution.

From the federal side, the criticism was renewed that the Lisbon Treaty (like the Constitutional Treaty) in no way replaces a “real” constitution in the federal sense they are striving for .

Of globalization critical side, about the German party Die Linke , was emphasized, among other things, that the Treaty of Lisbon is no answer to the social and democratic concerns raised in the referendums in France have led and the Netherlands to a rejection. It is true that the phrase “ internal market with free and undistorted competition” has been deleted from the EU's objectives ; At the same time, however, a protocol was agreed to ensure free and undistorted competition, so that this change was only of symbolic value.

This criticism was particularly virulent in France, where the referendum on the old constitutional treaty resulted in a narrow rejection. Nevertheless, France ratified the Lisbon Treaty in February 2008; The government claimed that it was a new treaty, which French constitutional experts rejected. Since the content of the Lisbon Treaty essentially took up those of the Constitutional Treaty, critics accused the French parliament of not acting in the interests of the people's will, but of ignoring the previous democratic vote.

Late publication

One of the criticisms of the treaty was the fact that the Council of the EU did not present the citizens with an overall presentation of the amended EU treaty and the amended EC or AEU treaty until April 16, 2008, i.e. several months after the contract was signed made available in all member languages. The translation of the text of the treaty as well as renegotiations on the details of individual formulations meant that initially no consolidated version of the treaty was published, although the ratification procedures had already started in several countries . The official publication of the new consolidated version in the Official Journal of the EU took place on May 9, 2008.

No solution to the institutional democratic deficit

The Lisbon Treaty expanded matters with the European Parliament's co-decision procedure , so that Parliament now has legislative powers on an equal footing with the Council of the EU in almost all policy areas. This is intended to meet an essential demand for overcoming the lack of separation of powers in the Council and thus for improving the democratic legitimation of EU legislation . In addition, according to the Treaty, the meetings of the Council should always take place in public when the latter takes legislative action, thus countering the allegation of lack of transparency. Nevertheless, in the eyes of the critics, important aspects of the EU's institutional democratic deficit remain unsolved. The German Federal Constitutional Court is also cautious about the Lisbon Treaty: It does not lead the Union to a new stage of development in democracy. The following are generally criticized:

- the still only indirect, indirect democratic legitimation of the EU Commission

- Maintaining the degressive proportionality in the distribution of seats in the European Parliament , which is seen as a violation of the principle of electoral equality (based on this, the European Parliament is referred to as a representation only of the different European peoples and not of a unified popular will) (see graphic)

- Parliament's still lacking right of initiative

- Parliament's continued lack of competences in foreign and security policy and

- the unclear distribution of competencies between national and European institutions (despite the newly introduced competency catalog)

Critics also fear that with the Lisbon Treaty, the process of increasing the EU's democratic legitimacy will be considered complete, although the task of the EU summit in Laeken to democratize the EU's structures remains unfulfilled. This criticism is based on the preamble to the Reform Treaty, according to which the aim of the treaty is to "complete the process by which the efficiency and democratic legitimacy of the Union are to be increased [...]".

An alleged glossing over of democratic conditions by the text of the treaty was also criticized. Art. 14 (1) TEU states that Parliament “elects” the President of the Commission; from Art. 17 (7) TEU, however, it emerges that this election takes place on the proposal of the European Council: Parliament can reject the candidate named by the European Council, but cannot make its own proposal.

Accusation of militarism

The defense policy provisions adopted from the constitutional treaty finally sparked a heated discussion. In the formulation of the common security and defense policy , the treaty mentions “civil and military means”, but emphasizes the latter too much. Particularly controversial is a passage in Article 42, Paragraph 3 of the EU Treaty in the version of the Lisbon Treaty, according to which the member states undertake to "gradually improve their military capabilities", which critics see as an obligation to rearm . In addition, the competencies of the European Defense Agency , for example in determining armaments requirements , are criticized.

Proponents oppose this by stating that Article 42 of the EU Treaty merely specifies the common security and defense policy , which is already anchored in the Maastricht Treaty as a Union objective and is already provided for in Article 17 of the EU Treaty in the version of the Treaty of Nice . In addition, they emphasize that the EU institutions may in principle only act in accordance with the general objectives of the Union listed at the beginning of the treaty, to which, according to Art. 3 EU treaty, among other things, the promotion of peace, mutual respect among peoples, The protection of human rights and the observance of the principles of the Charter of the United Nations count.

Alleged insufficient prohibition of the death penalty in the Charter of Fundamental Rights

One point of criticism in the public discussion was the view that the Charter of Fundamental Rights enables the reintroduction of the death penalty even in countries with an absolute ban (e.g. Germany or Austria). This accusation was based on the fact that Article 2, Paragraph 2 of the Charter states that no one may be sentenced to the death penalty or executed, but the explanatory notes on the Charter of Fundamental Rights that serve as an aid to interpretation and are not legally binding, this prohibition within the meaning of the European Convention on Human Rights interpret which, in the wording of the 6th Additional Protocol, allows, among other things, the death penalty in a state of war and a killing to put down a riot.

However, all EU member states (including Germany and Austria) have already ratified the 13th Additional Protocol to the European Convention on Human Rights of May 3, 2002, which prohibits the death penalty without exception in both peacetime and wartime. Any state can terminate this additional protocol at the earliest after five years with a notice period of six months. Due to the interpretation rule in Art. 52 Para. 3 and Art. 53 of the Charter, the protection of fundamental rights by the Charter may in no case be lower than that provided by other valid legal texts, in particular the constitutions of the Member States or international conventions such as the European Convention on Human Rights, is guaranteed. The Charter can therefore only introduce new fundamental rights, not reduce the existing protection of fundamental rights.

The allegation of the inadequate prohibition of the death penalty was represented in the German-speaking area primarily in Karl Albrecht Schachtschneider's application before the German Federal Constitutional Court. However , the Constitutional Court did not address this aspect in the Lisbon judgment .

See also

literature

- Europe to Lisbon. (PDF; 5 MB) In: From Politics and Contemporary History 18/2010.

- Klemens H. Fischer: The Treaty of Lisbon . Text and commentary on the European Reform Treaty. 2nd edition, Nomos, Baden-Baden 2010, ISBN 978-3-8329-5284-6 .

- Clemens Fuest (Ed.): Lisbon Treaty. Have the course been set correctly? Law and politics of the European Union as a prerequisite for economic dynamism; VIII. Interdisciplinary Congress “Young Science and Europe”, 29. – 30. May 2008 in the Berlin-Brandenburg Academy of Sciences . Hanns-Martin-Schleyer-Foundation , Cologne 2008, ISBN 978-3-9812173-1-5 .

- Vanessa Hellmann: The Lisbon Treaty. From the constitutional treaty to the amendment of the existing treaties - introduction with synopsis and overviews. Springer, Berlin / Heidelberg 2009, ISBN 978-3-540-76407-6 .

- Markus C. Kerber (Ed.): The struggle for the Lisbon Treaty , Lucius & Lucius, Stuttgart 2010, ISBN 978-3-8282-0500-0 .

- Armin Kockel: Challenges, opportunities and perspectives after the Lisbon constitutional summit (PDF; 1.1 MB) In: Bucerius Law Journal, 2008.

- Olaf Leiße : The European Union after the Lisbon Treaty. VS Verlag, Wiesbaden 2010, ISBN 978-3-531-16072-6 .

- Julia Lieb, Andreas Maurer, Nicolai von Ondarza (ed.): The Lisbon Treaty. Short comment. SWP discussion paper FG01 2008/07. April 2008.

- Andreas Marchetti, Claire Demesmay (ed.): The Lisbon Treaty. Analysis and evaluation . Nomos, Baden-Baden 2010, ISBN 978-3-8329-3676-1 .

- Markus Möstl: Treaty of Lisbon. Introduction and commentary. Consolidated version of the contracts and accompanying German legislation. Olzog, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-7892-8326-0 .

- Ingolf Pernice (Ed.): The Treaty of Lisbon: Reform of the EU without a constitution? Nomos, Baden-Baden 2008, ISBN 978-3-8329-3720-1 .

- Rudolf Streinz , Christoph Ohler , Christoph Herrmann: The Treaty of Lisbon to reform the EU. Introduction with synopsis. 3rd edition, Beck, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-406-59776-3 .

- Werner Weidenfeld (ed.): Lisbon in the analysis. The reform treaty of the European Union . Nomos, Baden-Baden 2008, ISBN 978-3-8329-3524-5 .

- Udo di Fabio : Future of the European Union: Cheer up! In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung

Web links

Documents

- Lisbon Treaty of December 13, 2007 .

- Treaty on European Union and Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union in the consolidated versions of March 30, 2010 .