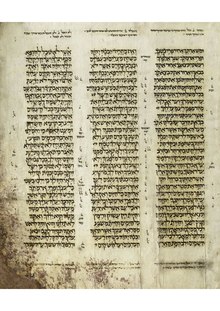

Aleppo Codex

The Codex of Aleppo ( Hebrew כתר ארם צובא, Keter ("crown") Aram Tzova ) was the oldest complete manuscript of the Masoretic Hebrew Bible until it was damaged in 1947 . It now comprises 295 of the original 491 sheets and is located in Jerusalem in the Israel Museum in the Shrine of the Book .

Emergence

The original text of the Codex consisted only of consonants and was copied by Sh'lomo ben Buya'a in or near Tiberias (Israel) around 920 AD . This copy was checked, vocalized and given Masoretic annotations by the Masoretician Aaron ben Moshe ben Ascher . Aaron was the last and most famous member of the Ben Ascher grammar family from Tiberias, who formed the most accurate version of the Masorah and therefore the Hebrew Bible.

The handwriting was intended as a sample code from the start. It should only be read from it on Passover , Shavuot (= festival of weeks) and Feast of Tabernacles ; otherwise it was only available to scholars to clarify questions of doubt. It was not intended for “normal” Bible study.

history

In the middle of the 11th century , about a century after it was written, the Codex came into the hands of the Karaite community of Jerusalem, apparently after it was bought from the heirs of Aaron ben Ascher. Not long afterwards it was taken as booty from Jerusalem (either in 1071 by the Seljuks or in 1099 by the Crusaders ) and eventually reappeared in the rabbanite synagogue in Cairo, where it was used by Maimonides . Maimonides' descendants brought him to Aleppo (Syria) at the end of the 14th century . The Aleppo community guarded it so carefully for six centuries that it was almost impossible for outsiders to investigate. In particular, permission to make a complete film was always refused. Later it turned out, however, that photographs of individual pages still exist, for example from the years 1887 (Gen 26.37–27.30) and 1910 (Dt 4.38–6.3).

During the Aleppo pogrom in December 1947 , the Aleppo Central Synagogue was set on fire and destroyed. The Codex was initially considered lost. As it turned out later, large parts of the Codex could be saved. The exact circumstances of the damage and its whereabouts in the following years are still debatable today. Aleppo Jews claim the missing leaves were burned; On the other hand, the leaves obtained show no signs of exposure to fire, so they must have been brought to safety in good time. The dark spots visible today on the side edges and corners are probably due to bacterial or fungal attack. In addition, the instability of the ink posed particular challenges for the conservators at the Israel Museum. In view of their age, the surviving pages of the manuscript are, according to information from the Israel Museum, in “remarkably excellent condition”.

In January 1958 the Codex was brought to Jerusalem, where it is still located today, under circumstances that were not entirely clear. A massive dispute broke out over the authorization of the messenger to deliver the Codex to the Israel Museum. Rabbis from Aleppo believe that the Codex should only have been given to them. On December 31, 1981, the board of the manuscript department at the Jewish National and University Library was given a sheet from the chronicle books. Part of a page from the book Exodus became known to scholars at the Ben-Zvi Institute in 1987. Another page appeared in November 2007. She was saved from the synagogue fire in 1947. The appearance of these previously lost pages could mean that other pages are still available somewhere. Some scholars suspect that the missing sheets could have been torn out in 1947 by members of the Jewish community and hidden privately.

This contrasts with the assumption expressed in an article in the New York Times on July 25, 2012 that almost all of the Codex was handed over to the Israel Museum in 1958. The director of the Ben Zwi Institute at the Israel Museum, Meir Benayahu, had never compiled a proper catalog of the incoming books, and numerous manuscripts had disappeared from the holdings during his tenure until his release under unexplained circumstances in 1970. The Israeli journalist for archaeological and religious topics Matti Friedman writes in his book The Aleppo Codex : “We only have this one fact left: The Crown of Aleppo came at the end of January 1958, at a time when a significant part of the manuscript was missing had not yet been documented, in the care of a library where the books were not safe. In March of the same year, 200 pages were found missing. Over the decades, the scientists at the Ben Zwi Institute repeatedly let the public know that they were looking for the missing parts all over the world. They searched old Aleppo, Brooklyn, São Paolo and Rio de Janeiro. They asked a clairvoyant in Switzerland to move the location on maps of southern Lebanon. They looked, it seems, everywhere - just not in the mirror. "

A Judaica collector claimed in 1993 that he had been offered for sale in Jerusalem in the mid-1980s 70 to 100 pages, which he believed to be pages from the Aleppo Codex. He did not want to pay the asking price, so the collection went to a collector in London whose name he would not disclose.

scope

The book, which was smuggled into Israel in 1958, contained 294 pages written on both sides. Essential parts of the beginning ( Pentateuch ) and the end of the manuscript as well as individual pages from the middle are missing . A total of 196 of the original 491 pages were missing.

The current text begins with the last word of the 4th book of Moses in chapter 28, verse 17 (ומשארתך, "and your baking trough").

This is followed by the books Joshua, Judges, 1st and 2nd Samuel, 1st and 2nd Kings, Isaiah, Jeremiah , Ezekiel, Hosea, Joel, Amos, Micha, Nahum, Habakkuk, Zefaniah, Zechariah, Malachi, 1st and 2nd Chronicle, Psalms (15-25: 1 missing) up to 148, then from Job 1.16b Lut , Proverbs, Ruth, Song of Songs .

The last leaf ends with בנות ציון in Song of Songs 3:11 ("come out and see, you daughters of Zion ...").

The following are missing in particular: The end of the Song of Songs, Kohelet, Lamentations of Jeremiah, Esther, Daniel and Esra / Nehemia.

The missing pages are apparently due to the damage in 1947.

meaning

The Codex of Aleppo is considered by many Jewish groups to be the most authoritative source for the biblical text as well as for the vocalization and cantillation , as it has been shown to follow the Masoretic principles of the Ben Ascher school most faithfully. It is also considered to be the most authoritative document of the Masorah ("Tradition"), the tradition by which the Hebrew Scriptures have been preserved through the generations. See also masoretic text .

This assessment is based on the fact that the Aleppo Codex was the manuscript used by the rabbi and scholar Maimonides (1135–1204) when he laid down the precise rules for writing Torah scrolls in his Mishneh Torah ( Hilkot Sefer Torah , “The Laws of the Torah Scroll "). However, Maimonides only cited him for the division into sections and other formatting issues, but not for the wording itself. "The codex we used in this work is the one known in Egypt that was in Jerusalem and contains 24 books," he wrote.

The work of Moshe Goshen-Gottstein to the few remaining pages of the Torah seems to confirm that the Aleppo Codex was used by Maimonides manuscript indeed. In the introduction to his facsimile reprint of the Codex, Goshen-Gottstein rates the Codex of Aleppo not only as the oldest one-volume Tanach , but as the first complete Tanach produced by one or two people as a uniform work in a consistent style.

In Christian biblical studies, the Aleppo Codex is seen as one of the most important and oldest witnesses to the Masoretic text and is included in academic text editions.

The Codex has been a UNESCO World Document Heritage since 2015 .

Modern editions

The Aleppo Codex is the source of several modern editions of the Hebrew Bible, including the edition by Mordechai Breuer , the Hebrew University Bible Project (previously published: Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel) and the "Jerusalem Crown": the latter follows the Page layout of the Codex, offers a text based on Breuer's work and was printed in Jerusalem in 2000. A newly designed type was used, which is based on the calligraphy of the Codex.

This edition of the Bible is used in Israel for the swearing-in of the President.

See also

literature

- Matti Friedman: The Aleppo Codex: In Pursuit of One of the World's Most Coveted, Sacred, and Mysterious Books. Algonquin Books: Chapel Hill 2012. ISBN 978-1-61620-040-4

- Moshe Goshen-Gottstein: The Authenticity of the Aleppo Codex, in: Textus 1 (1960), pp. 17-58.

- Hayim Tawil, Bernard Schneider: Crown of Aleppo: The Mystery of the Oldest Hebrew Bible Codex. Jewish Publication Society: Philadelphia 2010. ISBN 978-0-8276-0895-5

- Ernst Würthwein : The text of the Old Testament. An introduction to the Biblia Hebraica. 4th expanded edition. Württemberg Bible Institute, Stuttgart 1974, ISBN 3-438-06006-X .

- Israel Yeivin: The Aleppo Codex of the Bible: A Study of its Vocalization and Accentuation (= Publications of the Hebrew University Bible Project , Monograph Series 3). Magnes Press: Jerusalem 1968.

Web links

- The Aleppo Codex Website Images of the entire text with optional enlargement as well as background information on the history and meaning of the Codex (English and Hebrew).

- The Aleppo Codex - Mikraot Gedolot Haketer Website (scan and transcription)

- Mechon Mamre - Parallel text versions (English, French)

- Text of the Aleppo Codex as a free download module for MyBible (freeware Bible program)

- History of the Codex of Aleppo , English

- Segal, The Crown of Aleppo , English

Remarks

- ^ Rival Owners, Sacred Text , Wall Street Journal. June 12, 2013. Retrieved July 24, 2017.

- ↑ Ernst Würthwein: The text of the Old Testament , p. 39, footnote 3

- ^ Benny Morris: 1948: a history of the first Arab-Israeli war . Yale University Press, 2008, pp. 412 ( limited preview in Google Book Search [accessed July 24, 2017]).

- ^ Hayim Tawil, Bernard Schneider: Crown of Aleppo: The Mystery of the Oldest Hebrew Bible Codex . Ed .: Jewish Publication Society. 2009, ISBN 978-0-8276-0895-5 , pp. 163 ( limited preview in Google Book Search [accessed July 24, 2017]).

- ^ Yosef Ofer: The Aleppo Codex Today. Retrieved October 10, 2019 .

- ^ A b c d New York Times: The Aleppo Codex Mystery , July 25, 2012

- ^ Adventure archeology online , November 7, 2007

- ^ Matti Friedman: The Aleppo Codex. A Bible, the Mossad and the state secret of Israel . Herder, Freiburg 2012, ISBN 978-3-451-32539-7 , p. 277.

- ↑ a b Yosef Ofer: The Aleppo Codex Introduction on the website of the online project

- ↑ The Aleppo Codex The Extant Parts of the Aleppo Codex on the website of the online project