Gall wasps

| Gall wasps | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Common oak gall wasp ( Cynips quercusfolii ) |

||||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||||

| Cynipidae | ||||||||||||

| Latreille , 1802 |

The gall wasps (Cynipidae) are a family of hymenoptera (Hymenoptera) and are classified here within the waist wasps (Apocrita) in the superfamily of gall wasps (Cynipoidea). Over 1400 species are known worldwide.

features

The gall wasps are mostly small animals with a body length of one to three millimeters, exceptionally up to eight millimeters, and are usually colored black or drawn inconspicuously. The antennae in the males always have one more link than in the females, typically 13/14 or 14/15 segments. The trunk section (mesosoma) is usually very short and high and compact when viewed from the side. The free abdomen (metasoma) is attached to a short stalk (petiolus), which consists of one segment (the second abdominal segment). The rest of the abdomen is noticeably tall and narrow; when viewed from the side, it is round to oval in shape. The ovipositor of the females is of various lengths from almost body length to very short, at the same time very thin and flexible. In the resting position it is almost completely hidden in the abdomen, where it can form a complete loop. The wing vein has the characteristic shape of the gall wasp-like: the marginal vein (costa) and a wing mark (pterostigma) are always missing. In the basal half of the fore wing, two longitudinal arteries are formed (interpreted as a fused radius + subcosta and media + cubitus), the rear of which can be indistinct. In the front center of the wing there is a characteristic, triangular-shaped cell, which in gall wasps is usually open towards the edge of the wing. Another longitudinal artery (usually interpreted as media) runs from it towards the wing tip. Usually only one vein is visible in the small hind wing. Very few species are short-winged (brachypter) or wingless (apter).

It is difficult to differentiate the gall wasps from their sister family Figitidae , with which they form the so-called microcynipoidea. Differences concern the microsculpture of the mesoskutum (upper part of the fuselage between the wings), which is matt in the Cynipidae due to microscopic granulation and almost always glossy in the Figitidae. Most Figitidae also have either two strong lateral keels on the pronotum or a conspicuous, raised pronotum plate. The third abdominal tergum (upper abdominal plate) is usually the longest in gall wasps, and the fourth in Figitidae. The main difference, however, is the articulation of the ovule and not visible from the outside.

The gall wasp eggs are elongated oval and have a characteristic stalk. The egg is considerably thicker than the diameter of the female's ovipositor, so that when the egg is laid it is squeezed and elongated; the stalk region then serves to absorb the excess volume. The length of the egg without the stalk is approx. 0.2 millimeters. The larvae have the typical shape of the hymenoptera larvae ("hymenopteriform"), they are legless, with the exception of the head capsule, softly sclerotized and colored white. The mandibles of the gall wasp larvae have two blunt teeth, while the larvae of the parasitoid forms usually only have one sharp tooth (sometimes also smaller teeth or a cutting edge).

Reproduction and development

The larvae of all gall wasps live and develop inside the growths of plant tissue that they themselves trigger, the plant galls . Their nutritional basis is therefore vegetable (phytophag), an exception within the Legimms. The bile arises as a growth as a result of the puncture with the ovipositor. The galls have a species-specific shape and are in many cases easier to identify than the insect that caused them. The exact processes involved in the formation of bile have not yet been clarified. It is clear that hormonally acting substances are released that reverse the plant's growth programs themselves and use them for themselves. Induction by the egg itself is considered unlikely. The hypothesis is currently being tested that the poison released from the poison gland in the abdomen contains the gall-inducing substances. It had previously been noticed that the female gall wasp not only retained the venom gland, but that it is usually particularly large. Since it would no longer be needed to paralyze a host organism, a new function suggests itself. Later the larva itself is involved in further gall induction. The bile usually consists of a hard shell and a soft tissue inside that the larva uses for nutrition. Outside the hard shell there is usually additional, softer tissue, often covered with hair or other growths. The larva usually sits in a small, open chamber inside. The bile only develops further if the larva is present. The female lays the egg in a carefully selected, species- and stage-specific location, usually with only one particular plant species or genus. Galls occur on flowers, leaves, stems, twigs, buds and roots. Depending on the species, a bile consists of one to several hundred chambers with one larva in each. The gall wasp larva lives exclusively within the bile and also pupates there. The hatching gall wasp eats a circular hole in the shell with its mandibles, from which it hatches. As with all waist wasps, the rectum of the larva is closed. Feces are only released once, immediately before pupation, as so-called meconium .

A line of development of the gall wasps ( tribe Synergini) has switched to laying their eggs not in normal plant tissue, but exclusively in the young galls of other gall wasp species. The hatching larva sometimes kills the original gall dweller, or it is killed when it is stung. Often this is simply displaced by the nutrient tissue and then starves to death. This way of life is known as “one-tenant” or “ equiline ”. Despite the somewhat harmless sounding name, it is a variant of the ( klepto- ) parasitoid way of life, as it almost always leads to the death of the actual gall producer. Exceptionally, however, there are some equilines that encapsulate themselves from the original gall producer, so that both survive. Galls occupied by equilines continue to grow with the new user, sometimes with a slightly different shape. Most of the time, the equilines are just as host-specific as the original gall producers themselves.

Many gall wasps, especially a relatives that attack oaks (tribe Cynipini), show a generation change with a bisexual and a parthenogenetic generation every year , this is known as "heterogony". The different generations differ in their appearance and in the shape of the plant galls they induce . In many cases, the sexual and asexual forms have been described twice, as different species, and their identity was only later recognized. Other species, such as the rose gall wasp Diplolepis rosae , reproduce almost exclusively (thelytok) parthenogenetically. Males have so far been observed in all species - albeit sometimes very rarely.

The host plants and also the shape and size of the gall are species-specific, with around 80% of the native species living on different organs of oaks . Galls can be found in almost all parts of the trees, for example on the leaves , buds , branches and roots . Other species live in the rose family or on maple and many other host plants. The identification of the species is often much easier with the galls than with the insects themselves.

distribution

The center of distribution of the gall wasps is in the moderate (temperate) latitudes of the northern hemisphere. Most genera and species worldwide are found in the Mediterranean region and around the Black Sea. No species are found in the tropics, although some penetrate further south in the mountains. Only four genera have been described from the temperate latitudes of the southern hemisphere, two each from South America and South Africa. There are no endemic gall wasps in Australia. However, a number of species have been introduced almost worldwide today.

Around 100 species have been recorded in northern Central Europe.

Host plants

Gall wasps are gall producers on dicotyledonous plants. Only one species of monocotyledons is known worldwide , the North American Diastrophus smilacis on stinging winds ( Smilax ). The morphologically most primitive species produce galls, predominantly perennial, herbaceous plants, especially poppies, mint family and daisy family. A very species-rich development line lives on rose plants, including both shrubby and herbaceous species. A single, but very species-rich line of development lives on oaks. Few species live on other deciduous tree species, especially maple (in Germany only Pediaspis aceris ).

A selection of native species

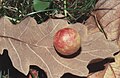

Gallapfel the commons Eichengallwespe ( Cynips quercifolii )

Gall apple of the striped oak gall wasp ( Cynips longiventris )

Most species of gall wasps live as gall-formers on oaks. The best known of these oak gall formers is the common oak gall wasp ( Cynips quercifolii ), which forms characteristic galls up to two centimeters long on the underside of oak leaves. These turn reddish in autumn and are popularly known as gall apples . Light lenticular galls on the underside of the same sheets forming the Eichenlinsengallwespe ( Neuroterus quercusbaccarum ), darker with beaded edge Neuroterus numismalis . The galls of Cynips longiventris , which can also be found on the underside of the leaf and are characterized by their spherical shape and irregular red stripes, are also very striking . The sponge gall wasp ( Biorhiza pallida ) also lives on oaks , whose galls can be up to four centimeters in size and are round. They are known as oak apples or potato gall . In this species, the galls of the sex animals do not form on the leaves, but on the roots of the oak. The hard-shelled galls of the species Andricus kollari and Andricus quercustozae are often found on the buds of young oak branches .

The galls of the common rose gall wasp ( Diplolepis rosae ), which are known as rose apple, sleeping apple or bedeguar, are very noticeable . They are located on the ends of the shoots of roses and have a diameter of up to five centimeters and have long hair-like growths. There are several chambers within the bile, each of which is inhabited by a larva.

Taxonomy and systematics

The over 1400 species are assigned to 74 genera in around 9 tribes . The following is a list of the genera and tribes:

- Aulacideini (9 genera, 75 species)

- Aylacini (18 genera, 122 species)

- Ceroptresini (1 genus, 21 species)

-

Cynipini (34 genera, approx. 1000 species)

- Acraspis

- Amphibolips

- Andricus

- Aphelonyx

- Atrusca

- Barucynips

- Bassettia

- Belonocnema

- Biorhiza

- Callirhytis

- Cerroneuroterus

- Chilas

- Coffeikokkos

- Cyclocynips

- Cycloneuroterus

- Cynips

- Disholcaspis

- Dryocosmus

- Eumayria

- Heteroecus

- Kinseyella

- Latuspina

- Loxaulus

- Neuroterus

- Odontocynips

- Philonix

- Phylloteras

- Plagiotrochus

- Pseudoneuroterus

- Trichagalma

- Trigonaspis

- Xanthoteras

- Zapatella

- Zopheroteras

- Diastrophini (4 genera, 32 species)

- Diplolepidini (2 genera, 58 species)

- Eschatocerini (1 genus, 3 species, Neotropic)

- Paraulacini

- Pediaspidini (2 genera, 2 species)

- Qwaqwaiini

- Synergini (8 genera, 180 species)

Genera with wingless Imagines : Acraspis , Philonix , Phylloteras and Trigonaspis .

Others

The galls of several species, especially those of the Mediterranean, were previously used to extract tannin .

literature

- Jirí Zahradnik : bees, wasps, ants. The hymenoptera of Central Europe . Franckh-Kosmos, Stuttgart 1985, ISBN 3-440-05445-4 .

- Heiko Bellmann : bees, wasps, ants. Hymenoptera of Central Europe . Franckh-Kosmos, Stuttgart 1995, ISBN 3-440-06932-X .

- ID Gauld, B. Bolton: The Hymenoptera . Oxford 1988.

- K. Honomichl, Heiko Bellmann: Biology and ecology of insects . 1994.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d Family Cynipidae - Gall Wasps. bugguide.net, accessed September 16, 2018 .

- ↑ H. Vardal, G. Sahlen, F. Ronquist (2003): Morphology and evolution of the cynipoid egg (Hymenoptera). Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 139: 247-260.

- ↑ Jose Luis Nieves-Aldrey, Hege Vardal, Fredrick Ronquist (2005): Comparative morphology of terminal-instar larvae of Cynipoidea: phylogenetic implications. Zoologica Scripta 34: 15-36.

- ↑ Hege Vardal (2004): From parasitoids to gall inducers and inquilines. Morphological evolution in Cynipoid wasps. Diss., Univ. Uppsala. Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis 932.