Daara

Daara ( Wolof , also written dahra or dara , from Arabic دار, DMG dār 'house') is a traditional Islamic educational institution in Senegal that still plays a very important role in the country's educational system. The Daara is usually led by a marabout or sheikh , who is addressed as a Sérigné ("master") and who belongs to a Sufi brotherhood . The Daara disciples, called talibés , are mostly between six and 19 years old today. The main goals of Daara training are to memorize the Koran and impart basic knowledge about the religious duties of Islam . Another important aspect of Daara education is that the talibé should learn to respect and love and serve the Sérigné.

Until the 1880s, the Daara was the only educational institution in Senegal that was open to Muslims. Even today, many Senegalese receive their religious socialization in such an institution. According to estimates by the Senegalese Minister of Education, around 800,000 to one million children attended a Daara in 2002. In 2009 there were a total of around 6,000 Daaras in Senegal, of which just under 1,000 were in the capital Dakar . The number of students on the Daaras varies between 50 and 300, some large Daaras such as Coki's even have 1,000 students.

Because of its negative social effects (including the spread of forced begging), the Daara system has come under strong criticism in recent decades. It is currently in a comprehensive reform process in which both state authorities and various international non-governmental organizations are involved.

The different types of Daara

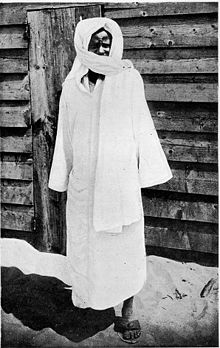

In 2004 Jean-Émile Charlier distinguished between three different types of Daaras: 1. traditional Daaras, 2. modern Daaras and 3. Daaras, which function as part-time Koran schools. The traditional Daaras are mostly located in cities and are characterized by the fact that they have no financial basis. The parents who entrust the marabout with their children do not give him anything in return for their upbringing. The students therefore live in poverty and have to go begging to support themselves, the marabout and the daara. They spend a lot of time on the street with their begging bowls, usually unwashed and clad only in rags. In return for their services, the marabout teaches them to read and write, teaches them the Koran and gives them basic knowledge of the Islamic religion. Disciples who do not submit to his authority are chastised. The humiliation and suffering that students experience in Daara are intended and are considered part of their moral education. The Talibés should learn to somehow "get by".

What Charlier calls "modern daaras" are boarding schools that are far from the cities in the countryside. The students receive a strict religious education here and to secure the livelihood of the Daara they do agricultural work for the marabout. The modern daaras also require that the families of the students make a financial contribution to the upkeep of the daara. Such agricultural Daaras are especially during the French colonial period of the Mouride was founded -Bruderschaft (see. Below) and here daara tarbiya called, but also some of the Daaras Tijaniyyah equivalent type. The living conditions in the modern type daaras are considerably better than in the traditional daaras. Since most of the Talibés live in the Daara until they get married, she forms a surrogate family for them. The talibé cannot leave the daara until the marabout has performed a ceremony of thanks ( gërëm ). A special characteristic of the Daaras of the Murīdīya is that it is reserved only for male disciples, while the Daaras of the Tijānīya also accommodate girls. However, strict gender segregation is maintained.

In the traditional and modern daaras, students live in this facility and very rarely see their parents. They live there as talibés until they get married. This is different with those Daaras who function as part-time Koran schools. They are only attended in the evening or during the holidays by the students who receive their regular education at a French-speaking state school. While in this case the French school has the task of preparing the students for this worldly life ( jàng àdduna ), the Daara is supposed to prepare them for the other worldly life ( jàng àllaaxira ). Unlike the traditional and modern daaras, the part-time daaras no longer have full authority over their students. In recent years, such part-time Daaras have grown in importance. In 2007, only 10 percent of Senegalese children between the ages of 6 and 12 attended a full-time Daara, while 50 percent attended a part-time Daara.

The validity of Charlie's typification for the immediate present is limited by the fact that the state supervisory authority for the Daaras, which was created a few years ago, now provides a definition for what it recognizes as a "modern Daara" and financially supports. Accordingly, it is an institution that accepts students between the ages of five and 18, prepares them for memorizing the Koran and provides them with a high-quality religious education and basic skills in accordance with the fundamental cycle . They must observe ergonomic standards, didactic principles and hygienic regulations and comply with the applicable state regulations. There are also a number of Daaras who participated in a state modernization program in 2002. They are called "modernized daaras" in the state diction. Because of this, Sophie d'Aoust divided the Daaras into four types in 2013: 1. traditional Daaras without boarding school, 2. traditional Daaras with boarding school, 3. modernized Daaras and 4. modern Daaras.

History of the institution

Origins

The historical origins of the Daara institution are obscure. In various recent studies, the relationship between the Daara and the medieval Ribāt is highlighted, in which adepts lived apart from the rest of the world and devoted themselves to their spiritual perfection. The Wolof word daara is also intended to refer to this context . It is supposed to be an abbreviation of the Arabic expression Dār al-murābiṭīn ( house of the border fighters ), which, like the term Ribāt in the nomadic society of West Africa, denoted an institution that served religious education, retreat and jihad .

In the period before the French colonization, the Daaras focused on memorizing the Koran. It was especially the sons from families of Muslim clergy who studied here in order to continue the family tradition and to prepare for a spiritual career. Children who did not come from clerical families usually left the Daara after a few years after they had learned the elementary rules of Islam, reading and writing and enough texts from the Koran to be able to pray correctly.

Developments during the French colonial period

A new form of Daara developed in the French colonial period with the Daara Tarbiya of the Murīdīya order. The Daara Tarbiya is a special institution of the Murīdīya and has also played a central role in the establishment and development of this Tarīqa . In the past, this form of Daara was described as an invention of Ibra Fall, a close follower of Amadu Bamba , but today it is assumed that this institution was not "invented" but developed very gradually, with Ibra Fall having little effect on this development Had a share. The Daara Tarbiya is seen as a strategy that Amadu Bamba and his early followers resorted to to cope with the ever-increasing number of disciples who gathered around them.

Bamba's father, Momar Anta Sali, founded a Daara in Mbacké-Kayor in 1871, which was mainly attended by older students. After his father died in 1883, Bamba continued the Daara of Mbacké Kayor, introducing a new style of upbringing, in which the goal was not so much the memorization of the Koran, but the "purification" and "taming" of the soul and education to community and solidarity. When Amadu Bamba later returned to his home village of Mbacké-Baol, he led the Daara there in the same way. The upbringing towards community was very important, especially in view of the heterogeneity of Bamba's followers. Many of his students were former slaves and members of the lower castes of the Wolof Society who had not received any schooling, others were former warriors.

The way Bamba led the Daara in Mbacké-Baol was heavily criticized by the local clergy and his own family. These conflicts forced Amadu Bamba around 1888 to leave the village of Mbacké-Baol and found a new Daara village nearby. In this village, which he named Darou Salam, he developed the Daara leadership into a special type that he called Daara Tarbiya ("Daara of education"). The Daara Tarbiya emphasized the service of the Sufi Sheikh as a guide and spiritual mentor. This was based on the Chidma concept cultivated in many Koran schools (from Arabic ḫidma = "service"), but in a Sufi reinterpretation, because in the Daara Tarbiya the teacher-student relationship was based on the Sufi model of Murschid and Murīd designed. The disciple served his sheikh to receive his baraka and imitate his behavior. The reasons for entering the Daara Tarbiya varied greatly. Quite a few Talibés joined them at the request of their Sheikh.

The expansion of the Murīdīya over Senegal is closely related to the Daaras. The method of the Murīdīya was to colonize new areas in the interior as far away as possible from the state and to establish Daaras there, especially in Baol and Saalum . This task was entrusted to older, married followers who, as representatives ( jawrigne ) of the marabout, moved with groups of ten to 15 young murīden to the new Daaras, cleared the land there and cultivated millet , the staple food in Senegal at the time. They lived in the daaras with their wives and took care of their disciples. Thanks to the Daaras, not only the territory of the Murīdīya increased, but also the economic position of the Brotherhood.

With the orientation of Senegalese agriculture towards the cultivation of peanuts, the character of the daaras changed, because the peanut plantations had considerably larger cultivated areas. The Daaras also became "pioneer settlements in reclamation for peanut cultivation." Most of the Daaras developed into real villages after a while, which were then run by the Sheikh. Disciples who completed their spiritual training in the Daara usually received land from their sheikh. He also helped them get married and start a family. The former students usually settled near their previous Daara, where the land was more accessible and they could count on the support of the Sheikh and his students. The Daara thus guaranteed group cohesion between the Murīden in rural areas.

Similar to Amadu Bamba, Malik Sy , the Sy-Tijānīya, established a number of daaras, not only in Tivaouane , the center of his movement, but also in Saint-Louis , Dakar and other cities in Senegal. To this day there are quite a number of Daaras in Tivaouane. One of them, the Daara Alaaji Maalik, which is located in the perimeter of the mosque, is reserved for the descendants of marabouts. In Tivaouane a clear separation is maintained between the sons of marabouts and the sons of pupils, although Mālik Sy had actually outlawed such academic inequality in his writings.

In 1913 the Daaras were the most important educational institution in Senegal. Of the estimated 120,000 primary school-age children, 11,451 attended a daara that year, while only 4,014 attended a French primary school.

After Senegal's independence

When Senegal gained independence in 1960, the new government did not care about the Daaras. This was also due to the fact that, in their opinion, the francophone schools had already outstripped the Daaras in terms of importance. According to an official estimate from 1961, the number of children attending a Francophone school was 110,000, while the number of Talibés was only 66,000.

In reality, however, the Daara being expanded in the post-colonial period. The Murīdīya continuously expanded their Daara network. The last great wave of founding Daara took place under Serigne Saliou Mbacké , the fifth general caliph of the Murīdīya. During the reign of Abdou Diouf (1981-2000) he established numerous modern daaras in the Chelcom forest in the Kaffrine region .

The reform process

Criticism of the Daara system and first reform efforts

From the 1980s and 1990s, however, the daaras was increasingly perceived as a social problem. In many urban daaras, including those of the Tijaniya, forced begging remained the order of the day. Government officials, the French-speaking press and international human rights organizations publicly condemned the Daara as an educationally backward institution. With the explicit aim of alleviating the social hardship of begging Talibés, several women founded the Daara Malika in 1980 with the support of President Léopold Senghor in northeast Dakar.

The focus of criticism, however, was not only begging, but also the unsanitary living conditions in the traditional Daaras and the corporal punishment generally used in the Daaras. After the United Nations had passed its Convention on the Rights of the Child in 1989 , the Senegalese government and UNESCO launched the first project to reform the Daaras in 1992, the results of which, however, are unknown. Other non-governmental organizations such as Tostan also got involved in the fight against the forced begging of the Talibés .

In 2002, the government of Abdoulaye Wade decided to reform the Daara system by integrating scientific and technical subjects into the curriculum and to bring it more under state control. With the support of UNICEF , she introduced a new curriculum at 80 selected Daaras in the Diourbel , Dakar, Kaolack and Thiès regions , introducing teaching in three languages (Wolof, French, Arabic) and vocational training. As hybrid educational institutions, these model daaras should combine the advantages of education at a state school and at a daara. The students who were included in the program (approx. 16,000) were to receive the Certificat de Fin d'Etude Elémentaire (CFEE) and then switch to a Franco-Arabic school. Of the 80 Daaras who took part in the UNICEF modernization program, however, 60 dropped out after three years because they lacked the means to teach according to the planned curriculum.

From now on, the Daaras were also included in the calculation of the school enrollment rate in order to be able to show better figures internationally. In 2004 the government also decided to set up a supervisory authority for the daaras ( inspection des daara ), which, however, was only able to start its work in 2008. In addition, the government tried to increase the public's acceptance of state schools by introducing religious instruction there. The aim was to get all children who had previously attended a Daara to attend a state school.

Start of reforms in the Senegalese population

The struggle of the state and non-governmental organizations to reform the Daara system found a lot of support from representatives of the state school system and business. Although the educational achievements of the agricultural Daaras were recognized in these milieus, the Daara also had a bad reputation among them due to the low level of training of their teachers and the lack of a teaching curriculum.

The influence of the state and non-governmental organizations as well as the planned replacement of the daaras by state schools also met with a lot of criticism. Since UNICEF did not work with the leaders of the Daaras, but mainly with the women ( ndeyu daara ) who directly look after the children in the Daaras, some Daara Sheikhs felt that the interference was undermining their authority and identified them as one Attack on Islam. In addition, many parents and even representatives of the business community were negative about the state schools. In some cases, pragmatic reasons were given for this, for example that the Daaras, with their strict rules and punishments, would prepare the Talibés better for life. In some cases, however, the parents also stuck to the Daara because the free teaching of the Koran, as is done in the Daara, is viewed by them as a beneficial activity and it is considered a pious act to send one's own children to a Daara . Finally, there are also social reasons that the parents hold to the Daara: by handing the child over to a Sérigné, a relationship of loyalty is established, which is considered very important in Senegalese society.

The "modern daara" project

Since the government had not succeeded in getting all children who attended a Daara to attend a state school, it decided on a new strategy, namely the "daara modern" project. With him, the population should be made an offer that meets their religious needs more closely. The concept of the "modern daara" stipulates that this institution's book begins at five and lasts for eight years. For the first three years, classes are taught in the local language, with a focus on memorizing the Koran. The second phase, which lasts for two years, includes memorizing the remaining part of the Koran and the material from the first three years of the state elementary school. In the third phase, which again comprises three years, the material from the last three years of elementary school is taught. At the end of the training, the state CFEE degree is awarded.

In January 2010, the Ministry of Education commissioned the organization PARRER ( Partenariat pour le retrait et la réinsertion des enfants de la rue ), which had previously been involved in the fight against forced begging by the Talibés, to develop a curriculum for these modern daaras. PARRER developed the new curriculum with financial support from Japan within one year. The PARRER curriculum, which aims to provide the Daara students with basic skills and at the same time a high quality Islamic education, was adopted in 2011 by the Daaras, which were already under state control.

PARRER also proposed a catalog of norms and standards for the modern daaras, which concerned the curriculum, staff, internal administration, infrastructure and equipment as well as hygiene and school books. This catalog was discussed at a workshop in July 2011. The supervisory authority has meanwhile begun drafting a law that will regulate the status of the Daaras in the long term and bring these institutions fully under the control of the state. A bill, which is accompanied by four executive decrees, has now been drawn up. It was presented in January 2015 by a delegation from the Ministry of Education to the General Caliphs of Murīdīya and Tijānīya. In the weeks that followed, there were heated discussions about the bill in the Senegalese media.

literature

- Christel Adick: "The educational system question in Senegal: Western and / or Islamic?" in Carla Schelle (Ed.): School systems, teaching and education in the multilingual French-speaking West and North Africa . Waxmann, Münster, 2013. pp. 31–44.

- Sophie D'Aoust: "Écoles franco-arabes publiques et daaras modern au Sénégal: hybridation des ordres normatifs concernant l'éducation" in Cahiers de la recherche sur l'éducation et les savoirs 12 (2013) 313–338. Online version

- Cheikh Anta Mbacké Babou: Fighting the Greater Jihad: Amadu Bamba and the Founding of the Muridiyya of Senegal, 1853-1913. Ohio University Press, Athens, 2007. pp. 105-108.

- Jean-Émile Charlier: "Les écoles au Sénégal: de l'enseignement officiel au daara, les modèles et leurs répliques" in "Cahiers de la recherche sur l'éducation et les savoirs: revue internationale de sciences sociales" 3 (2004) 35 -55. Online version

- El Hadji Samba A. Diallo: Les Métamorphoses des Modèles de Succession dans la Tijāniyya Sénégalaise. Editions Publisud, Paris 2010. pp. 312–327.

- Djim Dramé: L'enseignement arabo-islamique au Sénégal: le daara de Koki . L'Harmattan, Paris, 2015.

- Sophia Gaitanidou-Berthuet: Organization and network: the migration structure of the Mourids in Europe. Lit, Berlin, 2012. pp. 75-80.

- Sophie Lewandowski, Boubacar Niane: "Acteurs transnationaux dans les politiques publiques d'éducation. Exemple de l'enseignement arabo-islamique au Sénégal" in Diop Momar-Coumba (dir.): Sénégal (2000-2012). Les institutions et politiques publiques à l'épreuve d'une governance libérale . Karthala, Paris, 2013. pp. 503-540.

- Geneviève N'Diaye-Correard: Les mots du patrimoine: le Sénégal . Éditions des archives contemporaines, Paris, 2006. p. 159.

- Charlotte Pezeril: Islam, mysticisme et marginalité: les Baay Faal du Sénégal L'Harmattan, Paris, 2008. pp. 32–40, 151–166.

- Rudolph T. Ware III: "The Longue Duration of Quran Schooling, Society, and State in Senegambia" in Mamadou Diouf and Mara Leichtmann (ed.): New Perspectives on Islam in Senegal: Conversion, Migration, Wealth, Power, and Feminity. Palgrave Macmillan, New York, 2009. pp. 21-50.

- Rudolph T. Ware III: The Walking Qur'an: Islamic Education, Embodied Knowledge, and History in West Africa . University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, 2014. pp. 184-186.

Web links

- French documentary (2014) by Clothilde Hugon et Paraté Ba Yaméogo about the modernization of the Daaras in Senegal , brochure on the film

- Anti-Slavery International report on the forced begging of the Talibés

Individual evidence

- ↑ See Lewandowski / Niane: Acteurs transnationaux . 2013, p. 519.

- ↑ Cf. Ware III: The Walking Qur'an . 2014, p. 53.

- ↑ Cf. Ware: The Longue Durée of Quran Schooling . 2009, p. 36.

- ↑ Diallo: Les Métamorphoses des Modèles de Succession. 2010, p. 323.

- ↑ See Charlier: "Les écoles au Sénégal". 2004, para. 41.

- ↑ See Lewandowski / Niane: "Acteurs transnationaux". 2013, p. 519.

- ↑ See Charlier: "Les écoles au Sénégal". 2004, paras. 20–24.

- ↑ See Charlier: "Les écoles au Sénégal". 2004, para. 27.

- ↑ See Gaitanidou-Berthuet: Organization and Network . 2012, p. 78.

- ↑ See Charlier: "Les écoles au Sénégal". 2004, para. 25.

- ↑ Diallo: Les Métamorphoses des Modèles de Succession. 2010, p. 313.

- ↑ See Babou: Fighting the Greater Jihad . 2007, p. 105f.

- ↑ Diallo: Les Métamorphoses des Modèles de Succession. 2010, p. 320.

- ↑ Cf. Ware: "The Longue Durée of Quran Schooling". 2009, p. 37.

- ↑ Diallo: Les Métamorphoses des Modèles de Succession. 2010, p. 312.

- ↑ Cf. D'Aoust: "Écoles franco-arabes publiques et daaras modern au Sénégal". 2013, fn. 10.

- ↑ Cf. D'Aoust: "Écoles franco-arabes publiques et daaras modern au Sénégal". 2013, para. 9.

- ↑ See Babou: Fighting the Greater Jihad . 2007, p. 107.

- ↑ Diallo: Les Métamorphoses des Modèles de Succession. 2010, p. 314.

- ↑ See Babou: Fighting the Greater Jihad . 2007, p. 105f.

- ↑ See Babou: Fighting the Greater Jihad . 2007, p. 105f.

- ↑ See Babou: Fighting the Greater Jihad . 2007, p. 45f.

- ↑ Cf. Ware III: The Walking Qur'an . 2014, p. 183f.

- ↑ See Gaitanidou-Berthuet: Organization and Network . 2012, p. 75.

- ↑ See Gaitanidou-Berthuet: Organization and Network . 2012, p. 75.

- ↑ See Babou: Fighting the Greater Jihad . 2007, p. 67.

- ↑ See Babou: Fighting the Greater Jihad . 2007, p. 70.

- ↑ See Babou: Fighting the Greater Jihad . 2007, p. 70.

- ↑ Cf. Ware III: The Walking Qur'an . 2014, pp. 184f.

- ↑ See Gaitanidou-Berthuet: Organization and Network . 2012, p. 75.

- ↑ See Gaitanidou-Berthuet: Organization and Network . 2012, p. 75.

- ↑ See Babou: Fighting the Greater Jihad . 2007, p. 108.

- ↑ See Gaitanidou-Berthuet: Organization and Network . 2012, p. 75.

- ↑ Diallo: Les Métamorphoses des Modèles de Succession. 2010, p. 321.

- ↑ Diallo: Les Métamorphoses des Modèles de Succession. 2010, p. 318f.

- ↑ Cf. D'Aoust: "Écoles franco-arabes publiques et daaras modern au Sénégal". 2013, fn. 14.

- ↑ Cf. D'Aoust: "Écoles franco-arabes publiques et daaras modern au Sénégal". 2013, para. 11.

- ↑ Cf. Ware: "The Longue Durée of Quran Schooling". 2009, p. 37.

- ↑ See Adick: The educational system issue in Senegal. 2013, p. 37.

- ↑ Diallo: Les Métamorphoses des Modèles de Succession. 2010, p. 317.

- ↑ See Diallo: Les Métamorphoses des Modèles de Succession. 2010, p. 321.

- ↑ Cf. Ware: "The Longue Durée of Quran Schooling". 2009, p. 37.

- ↑ See Charlier: "Les écoles au Sénégal". 2004, para. 26.

- ↑ Cf. Ware: "The Longue Durée of Quran Schooling". 2009, p. 37.

- ↑ Cf. Ware: "The Longue Durée of Quran Schooling". 2009, p. 35f.

- ↑ See Charlier: "Les écoles au Sénégal". 2004, para. 42.

- ↑ See Adick: "The educational system issue in Senegal." 2013, p. 40f.

- ↑ Cf. D'Aoust: "Écoles franco-arabes publiques et daaras modern au Sénégal". 2013, paras. 20, 23.

- ↑ See Adick: "The educational system issue in Senegal." 2013, p. 41.

- ↑ Cf. D'Aoust: "Écoles franco-arabes publiques et daaras modern au Sénégal". 2013, para. 20.

- ↑ See Lewandowski / Niane: "Acteurs transnationaux". 2013, p. 528.

- ↑ See Charlier: "Les écoles au Sénégal". 2004, para. 41.

- ↑ See Charlier: "Les écoles au Sénégal". 2004, para. 25.

- ↑ See Charlier: "Les écoles au Sénégal". 2004, para. 9.

- ↑ Diallo: Les Métamorphoses des Modèles de Succession. 2010, p. 321f.

- ↑ See Charlier: "Les écoles au Sénégal". 2004, para. 28.

- ↑ See Charlier: "Les écoles au Sénégal". 2004, para. 29.

- ↑ Cf. Ware: "The Longue Durée of Quran Schooling". 2009, p. 38.

- ↑ Cf. Ware: "The Longue Durée of Quran Schooling". 2009, p. 38.

- ↑ See Adick: "The educational system issue in Senegal." 2013, p. 41.

- ↑ Cf. D'Aoust: "Écoles franco-arabes publiques et daaras modern au Sénégal". 2013, para. 25.

- ↑ See Lewandowski / Niane: "Acteurs transnationaux". 2013, p. 522.

- ↑ See the report by Anti-Slavery International 2011, p. 13.

- ↑ Cf. D'Aoust: "Écoles franco-arabes publiques et daaras modern au Sénégal". 2013, paras. 25, 26.

- ↑ The text can be viewed here.

- ↑ Cf. Mamadou Lo: "Projet de loi portant statut des« daaras »" in Le Quotidien January 15, 2015 Online ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. .