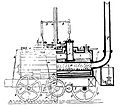

Steam car of the Royal Iron Foundry Berlin

The steam cars of the Königliche Eisengießerei Berlin were the first German steam locomotives .

background

After the end of the Napoleonic Wars , reports about the steam locomotives used in English coal mines reached Prussia . There was interest in introducing this new technology in Prussian mines. In 1814, the Brandenburg Upper Mining Authority sent two of its officials, the Upper Mining Authority Assessor Carl Heinrich Victor Eckardt and the ironworks inspector of the Royal Iron Foundry , Johann Friedrich Krigar , to England to study the locomotives used there. It was a classic case of industrial espionage .

Krigar and Eckart returned to Berlin in 1815 with plans for John Blenkinsop's locomotives . These were cogwheel locomotives , like the Blenkinsop-type locomotives, the steam engine drove a side cogwheel that engaged in a rack next to the rail and thus ensured the forward movement. The Prussians considered this English concept to be the most promising: Since during the experiments with "traveling engines" (ie with locomotives) in England the usual cast-iron rails of the horse-powered coal railroad broke under the weight of the machines within a very short time, Blenkinsop demanded that from Matthew Murray Build a machine that is as light as possible. Since this inevitably also reduced the friction weight of the locomotive, the drive was to be ensured by a special gear drive that Blenkinsop had designed specifically for this purpose.

In the spring of 1812 the company Fenton, Murray & Wood delivered the first two locomotives, "Prince Regent" and " Salamanca ", for the Middleton tram way and to Blenkinsop. On June 24th, 1812, the two machines began operating on the mine’s horse-drawn tram, which was meanwhile equipped with a cogwheel. The two machines were very successful and remained in operation until the Brandling company, to which the coal mines belonged, went bankrupt in 1834. In the first few years, the machines usually pulled 27 coal wagons (chaldrons) with a train weight of around 100 to 110 tons at a speed of around 6-7 km / h. A year later the two locomotives "Lord Wellington" and "Marquis Wellington" followed. Although the four machines did not even have a dead weight of 5 tons, they pulled trains of up to 38 coal wagons with a train weight of 140 tons at a speed of around 6 km / h. The four locomotives together replace a total of 52 horses and more than 200 men and were therefore considered a "great success".

The first steam car

In the course of 1815 and 1816 a locomotive of the Blenkinsop type was built under Krigar's management in the Royal Iron Foundry, the dimensions of which were smaller than those of its English models. The boiler was 2 meters long and 63 centimeters in diameter; the two cylinders were built into the top of the boiler . Their pistons, via a linkage, drove the gear, which was attached between the two barrel axles and only existed on one side. The track width was approx. 94 centimeters.

In June 1816 the steam car was completed. The tests showed that the vehicle was not very efficient: at a speed of only around 3 km / h, it pulled a car with a load of 2,570 kilograms. Despite the unsatisfactory results, the machine was dismantled as planned after the test, packed in 15 boxes and transported by water to Upper Silesia at the end of July , where it was supposed to pull the coal trains from the Königsgrube mine in Königshütte .

The locomotive was reassembled in Königshütte, but it was found that its gauge did not match that of the existing railroad. Since the boiler and cylinder were not tight, the locomotive was not put into operation and was later scrapped.

Geislauterner steam car

Although the first locomotive was not used and therefore no practical operating experience could be gained, the Royal Iron Foundry built another machine of the Blenkinsop type, which was completed in August 1817. This second steam wagon was intended for the Saar district and was supposed to transport the coal from the Altenkesseler Grube Bauernwald over the 2.5 km long Friederiken rail route to the loading point in Luisenthal on the Saar.

The factory tests of this locomotive showed that the performance fell short of the expected values. While comparable machines in England could pull 50 to 75 tons of load, the iron foundry's second steam car was only 4.2 tons. Nevertheless, this locomotive was also dismantled and sent to its destination.

On February 5, 1819 it arrived in Geislautern , where it was to be reassembled and subjected to extensive tests. These attempts dragged on for three years, and numerous defects in construction and execution soon became apparent: For a long time it was not even possible to set the machine in motion. The attempts to drive the locomotive failed, however, because the thin axles of the steam car could not bear the weight of the cast-iron boiler and bent. The plan to use them in the Bauernwald mine was therefore abandoned in January 1820.

It was not until October 1821 that the errors were found and repaired to the point where it was possible to get the locomotive running. The gear wheel attached to one side caused the vehicle to tilt on the track. In addition, the locomotive builders couldn't seal the boiler.

Numerous other quality defects, some of which were considerable and hardly rectifiable, made practical use of the machine impossible. The Bonn Mining Authority was reluctant to pay the bill for the unusable locomotive in 1823. It was then placed in an open wooden shed in Geislautern, where it stood for the next 11 years and deteriorated due to vandalism and theft of small parts. In 1834 the machine was offered for sale at the suggestion of the Bonn Mining Authority and in 1836 it was bought by a farmer for scrap metal for 334 thalers, 6 groschen and 7 pfennigs.

In 2014, a group of local historians from Saarland rebuilt the steam car as a demonstration model on a 1: 1 scale based on the original plans that were preserved. This is in the depot of the Nuremberg Transport Museum .

literature

- Karl-Ernst Maedel, Alfred B. Gottwaldt: German steam locomotives. The history of development . Transpress Verlag, Stuttgart 1999, ISBN 3-344-70912-7 .

- Kurt Pierson: Locomotives from Berlin . Motorbuch Verlag, Stuttgart 1977, ISBN 3-87943-458-1 .

- Hermann Maey, Erhard Born: Locomotives of the old German state and private railways . Steiger Verlag, Moers 1983, ISBN 3-921564-61-1 .

- Margot Pfannstiel : The locomotive king. Berlin pictures from the time of August Borsig . Verlag der Nation, Berlin 1987, ISBN 3-373-00116-1 .

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ The later legend, which has partly persisted to this day, that Blenkinsop and Murray, who were both talented engineers, did not understand the technical and physical principles of the locomotive and did not know the laws of friction at all, probably goes back to the description by Blenkinsop in the first Biography of George Stephenson by Samuel Smiles, whose author endeavored throughout his book to stylize his "hero", George Stephenson, as the sole inventor of the steam locomotive. Incidentally, Galileo had already dealt with the forces of friction and quite a few physicists in the following centuries made numerous attempts to elucidate these forces. The law of friction ( ), which is still valid today , was published by Charles Augustin de Coulomb in 1785 and already distinguished between static and kinetic friction in his presentation. Between 1786 and 1795, several studies of friction by Samuel Vince appeared in Great Britain . In addition, several engineers carried out experiments on "rolling friction" in this country between 1798 and 1806, of which Richard Trevithick and John Rennie were only the best known (a detailed account of the history of the study of the laws of friction can be found in: Peter J. Blau : Friction Science and Technology. 2002). By 1810, the laws on frictional forces were largely commonplace among engineers in Great Britain. In the further experiments of the railway pioneers, it was only a matter of determining the exact value of the friction of cast iron wheels on differently shaped cast iron rails ( denotes the specific coefficient of friction)

- ↑ with pure adhesion operation (i.e. with locomotives without gear drive) the locomotive would have had to be much heavier with the (known) friction values of the cast-iron rails of the time and the existing gradients of the railway line in order to be able to pull a train that was twenty-eight times heavier than its own weight. None of the rails that existed at the time would have borne such a burden.

- ↑ Source: Description of the vehicle on the model in the Nuremberg Transport Museum, July 1, 2017