Deir Turmanin

Coordinates: 36 ° 14 ′ 0 ″ N , 36 ° 49 ′ 0 ″ E

Deir Turmanin , also Turmanin, Der Termanin; was an early Byzantine settlement in the Dead Cities area in northwest Syria . The almost completely disappeared monastery church from the end of the 5th century was one of the most magnificent buildings in the region.

location

Deir Turmanin is located in the Idlib Governorate north of the main road that leads west from Aleppo to the Turkish border crossing at Bab al-Hawa . As in Roman times, the road runs through the plain of Dana, which is bordered in the south by the karst hills of the Jebel Barisha and in the north by the Jebel Halaqa, both of which are part of the northern Syrian limestone massif. Deir Turmanin is located at an altitude of 428 meters in the northeast of this agricultural plain, five kilometers east of Dana (north) and about eleven kilometers south of the early Byzantine monastery town of Deir Seman . The remains of the ancient settlement are a little higher on the edge of grain fields outside the modern village.

Site and history

The area was already settled in Roman times, as shown by a grave monument from the 2nd century AD that has been preserved in Dana. A few kilometers southeast of Deir Turmanin you can see a section of the Roman road between Aleppo and Antioch . The place experienced its heyday from the 4th to the 7th century. At the center was a monastery complex with a church and several residential and auxiliary buildings. The outer walls of one of these large buildings made of limestone blocks without mortar have been preserved up to the second storey height. They show a rural, simple style with rectangular, unprofiled window openings; attached vestibules rested on massive pillars.

basilica

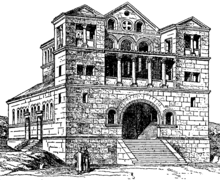

Deir Turmanin is not mentioned in the specialist literature because of these still visible remains, but because of its basilica from the end of the 5th century, which played an important role in the development of Syrian church construction. When Howard Crosby Butler visited the site in 1900 as part of an expedition from Princeton University in America, he found almost no more rubble. Knowledge of this church is based on the description of Melchior Comte de Vogüé, who found the building in an almost completely intact condition in the 1860s. There are no reliable sources as to what has happened to the Church in the meantime. With the wide arcade basilica of Qalb Loze completed a few years earlier (around 470) and the largest pilgrim church of Qal'at Sim'an (Simeon's monastery) oriented towards this, the church belonged to the northern core area, which was decisive for the development of the Syrian church building.

The three- aisled column arcade basilica had six columns in each row , which carried round arcades . At least one of the columns capitals on the clerestory was formed as Korbkapitell that should remind with its perpendicular, diamond-shaped pattern with a tank-shaped contour to a fruit basket. The transitions are made at the top and bottom with braided bands . This type of basket capital is likely to have Mesopotamian origins. The arcades ended on the western entrance side and on the triumphal arch of the apse in supporting pilasters .

While the round apse on the well-preserved church of Qalb Loze protrudes freely from the east wall, in Deir Termanin a very rare polygonal (pentagonal) apse was enclosed between lateral rectangular apse-side rooms. Such risalit-like protruding apse side rooms also existed in the Phokas church of Basufan at the same time . For the three large cathedrals, Qalb Loze, Deir Turmanin and Qal'at Sim'an, columns on the outer wall of the apse between the windows are typical, which supported the cornice . The pillars performed a decorative and static function in these buildings. In deliberate imitation of this style, some smaller churches took up this column arrangement, although there it seems rather attempted and makes less sense in terms of design. An example is the round apse on the south church of Bankusa and the basilica (north church) of Deir Seta , in which twelve small columns even appeared on a straight east wall. Both are in the Jebel Barisha area.

The north side of the apse was connected to the side aisle by an arched opening, which indicates its function as a martyrion ( relic chamber ); the southern side room served the clergy as a diakonicon , it was only accessible via a door from the side aisle. The church had two entrances each on the northern and southern long sides and another portal in the middle of the western gable side. A three-part narthex was built there, with towers on the sides that towered over the roofs of the aisles. Such a magnificently designed double tower facade was only owned by Qalb Loze in the area of the Dead Cities and the Bizzoskirche of Ruweiha in Jebel Zawiya to the south . For the Hauran area, a double-tower facade on the vanished five-aisled church of As-Suwaida is considered to be secure, for some other churches there are only guesses. Outside Syria, Deir Turmanin is cited as a model for the basilica of Jereruk in northern Armenia, which was probably built in the 6th century .

The representative corner towers are the redesign of a basic idea in churches that can be traced back to the Hittite Hilani courtyard house in the region via Greco-Roman temple and palace facades . The double tower facade came to full development in the European Romanesque .

literature

- Hermann Wolfgang Beyer : The Syrian church building. Studies of late antique art history. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin 1925, pp. 62, 65, 77 f, 152, 161 f

- Frank Rainer Scheck, Johannes Odenthal: Syria. High cultures between the Mediterranean and the Arabian desert. DuMont, Cologne 1998, p. 300, ISBN 3770113373

Web links

- Syria looks. naturales.wordpress.com (Photos)

Individual evidence

- ^ Syria, Places. index mundi

- ↑ Melchior Comte de Vogüé: Syrie centrale. Architecture civile et religieuse du Ier au VIIe siècle. J. Baudry, Paris 1865-1877, Vol. 2, Plates 130, 132-136

- ^ Friedrich Wilhelm Deichmann : Qalb Lōze and Qal'at Sem'ān. The special development of northern Syriac late antique architecture. Bavarian Academy of Sciences. Meeting reports, year 1982, issue 6, CH Beck, Munich 1982, p. 37

- ↑ Beyer, p. 161 f

- ↑ Beyer, p. 77 f

- ↑ Beyer, pp. 148-153