Symphony diagonal

| Movie | |

|---|---|

| German title | Diagonal symphony |

| Original title | Symphony diagonal |

| Country of production | Germany |

| Publishing year | 1925 |

| length | 149 meters, at 18 fps 7 minutes |

| Rod | |

| Director | Viking Eggeling |

| script | Viking Eggeling |

| production | Universum Film AG UFA |

| music | Olga Neuwirth (2006) |

| camera | Viking Eggeling, Meta Erna Niemeyer |

| cut | Viking Eggeling, Meta Erna Niemeyer |

Symphonie diagonale is the French title of the silent German experimental film Diagonal-Symphonie , which the Swedish-born painter and filmmaker Viking Eggeling completed in Berlin in 1924. From the 1910s onwards, Eggeling dealt with the integration of dynamic processes into his artistic work. After numerous studies and role models, he turned to film from 1920.

action

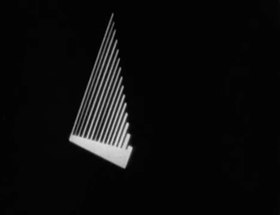

At the beginning you can see a tilting figure, which mostly consists of right angles, gradually getting bigger. Then there are short straight lines and curves that sprout from the existing design. The figure disappears and the process begins again with a new pattern. Each cycle takes about a second or two. All figures are drawn in an uncertain Art Deco style and are reminiscent of all sorts of things: that can be an ear, a harp, panpipes, a grand piano with trombones, etc., only abstracted to the highest degree. The mood is playful and has something hypnotic about it.

background

From 1918 Eggeling worked with Hans Richter on the unfinished film project “Horizontal-Vertical Orchestra”, which he gave up in 1922 in favor of his “Diagonal Symphony”. The Franco-German writer Ivan Goll helped him with the preparations, while Erna Niemeyer , who was studying at the Bauhaus in Weimar, assisted him with the animation of his templates .

The film, which was made under Eggeling's direction in the animation studios of Universum Film AG UFA , consists of single image recordings of characters that Eggeling cut from paper or tinfoil and started recording in the summer of 1923. He used self-designed pictures as templates, which he covered with black paper and slowly uncovered by moving the paper or cutting figures into the paper.

On November 5, 1924, the 149-meter-long film, which was around seven minutes long at 18 fps, was shown to friends for the first time in a private screening at the Gloria-Palast in Berlin ; on April 21, it was submitted to the Reich Film Censorship . It was presented to the public on May 3, 1925, 16 days before Eggeling's death, in Berlin as part of the matinee “The absolute film” organized by the Novembergruppe artists' association and the UFA in the UFA-Palast on Kurfürstendamm.

reception

The film was reviewed by Paul F. Schmidt in Das Kunstblatt and by BG Kawan in Film-Kurier in 1924. Additional articles on this were published by Adolf Behne in Die Welt am Abend and Willi Wolfradt in Das Kunstblatt 1925.

The Bauhaus teacher Ludwig Hilberseimer wrote about Eggeling in the Socialist monthly issue of August 10, 1925:

“The possibility of modifying a formal theme consequently led him to film. Because the film gave the means to develop an elementary thematic modification. After years of laborious work devoted to the analysis of art media, he succeeded in producing a few films as a synthesis of his work and thus realizing the moment of time, the process of form for the visual arts, introducing movement as reality into the visual arts. "

And Rudolf Kurtz wrote in his book "Expressionism and Film" in 1926:

“Eggeling addresses universal mental behavior; what he wants to express is the inner movement of people in its simplest form and with means that distance themselves from all adventurous and sentimental memories and only want to act as a simple, sharply specified being, in which molded parts to other molded parts in enter into a dynamic relationship. "

Film and music

“The short film is more of a visual than a musical 'symphony', a cacophony of geometric figures that appear one after the other like themes and motifs in a piece of music. What all figures have in common is that they are oriented either about 30 degrees positive or negative to the horizontal. "

In 1925, Eggeling had completely relied on the sound and rhythmic effect of his image montage, and in 1925 there was no music to accompany the “Diagonal Symphony”.

With regard to the sequence of forms, Eggeling orientated himself on compositional principles. The counterplay of the figures was understood as counterpoint, their sequence and changes in time as rhythm. Eggeling started from the idea of a universally valid abstract design language and used a handful of basic patterns that are expanded and varied in the course of the short film.

Due to his musical timing as well as his linear form drama of curves, lines, harps and triangles based on light-dark contrasts and changes of direction, Eggeling's work exerted a great influence on other contemporary artists, e. B. on László Moholy-Nagy or Walther Ruttmann .

According to a thesis of the Swedish film scholar Gösta Werner , the “Diagonal Symphony” was only a fragment, namely the first movement of a film symphony which Eggeling had designed for four movements.

In 2006 the Austrian composer Olga Neuwirth wrote music for Viking Eggeling's silent film.

literature

- John Coulthart: Symphony diagonal. In: feuilleton , August 18, 2008

- R. Bruce Elder: Harmony and Dissent. Film and Avant-garde Art Movements in the Early Twentieth Century . WLU Wilfried Laurier University Press, 2008, (PDF online)

- Alexander Graf, Dietrich Scheunemann (eds.): Avant-garde film (= Avant-garde critical studies . Volume 23). Verlag Rodopi, 2007, ISBN 978-90-420-2305-5 , pp. 19, 25, 34, 40.

- Ludwig Hilberseimer: " Art of Movement". In: Socialist monthly books. No. 27, Berlin May 23, 1921, pp. 467–468, (PDF online)

- Wolfgang Jacobsen, Anton Kaes, Hans Helmut Prinzler (Hrsg.): History of the German film. Filmmuseum Berlin - Deutsche Kinemathek, 2nd edition. Metzler-Verlag, 2004, ISBN 3-476-01952-7 , pp. 465-466.

- Christian Kiening, Ulrich Johannes Beil (Ed.): Rudolf Kurtz. Expressionism and Film. Chronos, Zurich 2007, ISBN 978-3-0340-0874-7 .

- Inka Mülder-Bach (Ed.): Siegfried Kracauer: Works. Volume 6: Small writings on film. Volume 3: 1932 - 1961.Suhrkamp -Verlag, 2004, ISBN 3-518-58336-0 , p. 47.

- Rudolf Kurz: Expressionism and Film . Verlag der “Lichtbildbühne”, Berlin 1926. (Reprint: published and with an afterword by Christian Kiening and Ulrich Johannes Beil. Chronos, Zurich 2007, ISBN 978-3-0340-0874-7 .)

- Eric Robertson, Robert Vilain (eds.): Yvan Goll - Claire Goll: Texts and Contexts (= international research on general and comparative literature. Volume 23). Rodopi Publishing House, 1997, ISBN 90-420-0189-5 .

- Hans Scheugl, Ernst Schmidt: A sub-story of the film. Lexicon of avant-garde, experimental and underground films. (= Edition Suhrkamp. Volume 471). Suhrkamp-Verlag, 1974, ISBN 3-518-00471-9 , pp. 241-243. (Zugl .: Mainz, Univ., Diss., 2003)

- Annika Schoemann: The German animation film: from the beginnings to the present 1909-2001 (= film studies. Volume 34). Verlag Gardez !, St. Augustin 2003, ISBN 3-89796-089-3 , pp. 121, 142, 321. (Zugl .: Mainz, Univ., Diss., 2003)

- Holger Wilmesmeier: German avant-garde and film. The film matinee “The absolute film” May 3 and 10, 1925. LIT Verlag, Münster / Hamburg 1994, ISBN 3-89473-952-5 .

- Friedrich von Zglinicki: The way of the film. History of cinematography and its predecessors. Rembrandt Verlag, Berlin 1956, DNB 455810680 .

Web links

- Symphonie diagonale in the Internet Movie Database (English)

- “Diagonal Symphony” with the music of Olga Neuwirth, posted on youtube

Items:

- Jörg Gerle: The absolute film. In: Film Service Reviews. fd13 / 2008. (PDF online)

- juh [d. i. Jan Ulrich Hasecke]: Absolute film and the demo scene . In: juh's sudelbuch. 2014. (sudelbuch.de)

- “Pupillary Intoxication and Optical Noise”. To the program of the matinee "The absolute film" 1925. (tu-berlin.de)

Individual evidence

- ↑ on this form of representation, which occupies an intermediate position between the static arts such as painting and the moving image of film, cf. kunstwissenschaft.tu-berlin.de

- ↑ Zglinicki p. 595 reports that Richter and Eggeling came across cinematography because they “noticed a clear movement in their abstract drawing themes as they were unrolled on long paper rolls” and then “decided to transfer their drawings onto film instead of paper rolls. "

- ↑ a detailed analysis of the film in RB Elder, Harmony and Dissent, pp. 460–464.

- ↑ cf. Graf-Scheunemann p. 34: "In 1923 Erna Niemeyer, then a young Bauhaus student, undertook to animate his“ Diagonal Symphonie ”scrolls. At this point Eggeling abandoned the“ Horizontal-Vertikales Orchester ”entirely."

- ↑ so Claire Goll in her memoirs Texts and Contexts on p. 85 and note 6

- ↑ cf. Zglinicki p. 596, where Niemeyer, however, appears with her pseudonym Renate Green, later Ré Soupault .

- ↑ cf. Zglinicki p. 596.

- ↑ cf. monoskop.org : “On April 21, 1925 Symphonie diagonale was certified by the German film censors. It was stated to have a length of 149 meters, which at a projection speed of 18 frames a second corresponds to exactly 7 minutes and 10 seconds. "

- ↑ cf. monoskop.org and Jeanpaul Goergen at diaf.de ( Memento from May 26, 2016 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Symphony diagonal. In: filmportal.de . German Film Institute , accessed on September 7, 2019 .

- ^ Schmidt, Paul F .: "Eggelings Kunstfilm". Das Kunstblatt (Berlin) No. 8, 1924, p. 381.

- ^ BG Kawan: Abstract Film Art. In: Film-Kurier. (Berlin) No. 276, November 22, 1924, p. 381, 3rd supplement.

- ↑ Vicking Eggeling. Berlin, May 23, 1925, reprinted in: Art of Time. Journal of Art and Literature. 3: 1/3 (1928), special issue Ten Years of the November Group. Berlin, p. 32.

- ↑ The absolute film. Volume 9, Berlin, 1925, pp. 187-188.

- ↑ on p. 517, cf. fes.de

- ↑ cit. at sudelbuch.de

- ↑ so "Huggo" at IMDb

- ↑ Jörg Gerle in: 'Filmdienst- Karten ' at unseen-cinema.com : “The presentation in May 1925 was mostly silent; very few, such as Hans Richter's contributions, had a musical concept. The pure, unadulterated movement was the "message," and perhaps that is why the matinee was closer to an understanding of the "absolute film" than any other performance. "

- ↑ Sandra Naumann at see-this-sound.at

- ↑ While Eggeling worked in “Diagonal-Symphonie” (1923/1924) with static, changing figurations of white lines, Ruttmann emphasized in his rhythm films (1921 to 1925) the spatiality of the film image through its depth moving geometric surfaces and figures.

- ↑ cf. Werner, Viking Eggeling Diagonalsymfonin (1997), cited above. at monoskop.org

- ↑ Duration: 9 '. It was first performed at the Viennale Festival on October 27, 2008, cf. works.php