A man like explosives

| Movie | |

|---|---|

| German title | A man like explosives |

| Original title | The Fountainhead |

| Country of production | United States |

| original language | English |

| Publishing year | 1949 |

| length | 114 minutes |

| Rod | |

| Director | King Vidor |

| script | Ayn Rand based on her novel |

| production |

Henry Blanke for Warner Bros. |

| music | Max Steiner |

| camera | Robert Burks |

| cut | David Weisbart |

| occupation | |

| |

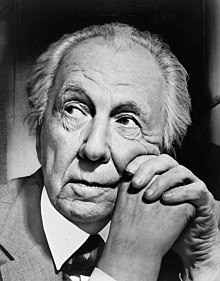

Fountainhead is an American movie from the year 1949. The by King Vidor with Gary Cooper staged in the lead role film based on the novel The Fountainhead ( The Fountainhead , 1943) by Ayn Rand is about an architect whose visions of a modern architecture met with little approval from his contemporaries. The book and the film are closely based on the life story of Frank Lloyd Wright .

action

The young architect Howard Roark is expelled from the academy because of his too modern designs. His architecture, which has elements of the international style , is not based on any model, which his teachers resolutely reject. Their view is that good architecture has to be based on the traditional and should copy the classical conceptions.

His friend and professional colleague Peter Keating, who adapted to survive, advises him to do the same. But Roark has his own visions, and the architect Henry Cameron is the only one who shares his views and offers him a job.

Years later, Cameron was broken by the narrow-mindedness of his contemporaries and the opinion leadership of the powerful publisher Gail Wynand. Roark, who has since taken over the office, is struggling to keep afloat financially because of his uncompromising attitude and his refusal to adapt to building fashions. The renewed advice of his friend Keating, who has meanwhile become a partner in a successful architecture firm, cannot convince him either. Even when he is on the verge of receiving a lucrative order for a new Security Bank skyscraper, he refrains from doing so when the supervisory board asks him to include a classical basement and historicizing facings in his concept.

The influential and high-handed architecture critic Ellsworth Toohey, who recommended Roark to Bank Roark, but only to see it fail, suggests Peter Keating as an alternative to the bank's majority shareholder, the cynical publisher Gail Wynand, but Wynand believes that he and Toohey are Mediocre. He wants to get the verdict of Keating's fiancé Dominique Francon, who, like Toohey, works as a columnist for his newspaper, the New York Banner.

Ms Francon, daughter of Keating's partner and a hardened woman, is disillusioned with the meanness of the modern world. She doesn't really love Keating and, like Wynand, thinks he is overrated and untalented. At a dinner with Ms. Francon, Wynand Keating holds out the prospect of the construction contract if he breaks off his engagement. Keating agrees and Wynand asks Dominique to marry him, but she refuses.

Roark is now bankrupt and has worked as a day laborer in a granite quarry. Ms Francon, who spends her vacation in her father's summer house nearby, visits the quarry and meets Roark, who immediately casts her spell on her. To see him again, she provokes a defect in a marble slab on the fireplace. When a new plate is delivered and about to be installed, she is furious that another worker will come to Roark's place. She confronts Roark and humiliates him. When he later comes to her house, she reluctantly lets himself be kissed (the scene here in the book, which at least comes close to a rape of Dominique by Roark, would not have been possible in a 1949 film itself).

When Roark receives a message from millionaire Roger Enright, who is planning a high-rise apartment building with him as an architect, he quits his job in the quarry. Since Dominique doesn't even know his name, she loses sight of him. The uncompromisingly modern design for the Enright Building, sparked by a campaign by the banner, which is launched by Toohey, makes the people's soul cook. Dominique, who is the only one who speaks out in favor of the construction of the unknown architect, confronts Toohey, who admits that he also considers the design to be great in private, but wants to campaign against too much genius in public. When she asks Gail Wynand to stop the campaign, she also bites granite. Then she resigns from her position.

At a reception to mark the opening of the building, she finally meets Roark. Later in his apartment, she confesses to him that on the one hand she loves him, on the other hand she cannot bear this circumstance, because she feels so dependent and vulnerable. For the same reason, she hated his design, even though she thought it was great. She is not ready to commit, also because she would not get over the, in her opinion, inevitable circumstance of seeing Roark ultimately fail because of his individuality because of the narrow-mindedness and envy of the public. So she finally gives in to Wynand's marriage proposal. She openly tells him that she doesn't love him, which Wynand accepts.

Roark, who happened to be watching the wedding ceremony, is without an assignment for a while after the Enright project. At the construction site of the city opera house, which his friend Keating designed and for which he was also considered, he meets the critic Toohey, who tries to explain his reasons for the dirt campaign, but Roark leaves him by the way. After a while he finally got a series of lucrative commissions until one day Gail Wynand asked him to design a luxurious residence for him and his wife. When Dominique accuses him of having used precisely this architect with the campaign at the time, Wynand cannot at first remember it. But when she says that Roark has triumphed over him with the Enright Building, Wynand wants to break his will out of hurt pride and provokes him by offering him all his projects for the future, which he should build in a mass-compatible style. When Roark pretended to be and sketched a tasteless Greek temple based on the design for the private residence, Wynand realizes that his plan has failed and gives in. So he and Roark eventually become friends.

Keating's star has since declined. In his desperation, he seeks help from Toohey, who is supposed to use his influence to get him a major project for a social housing estate. Toohey agrees. Over time, however, Keating realizes that he is not up to the requirements of such a mammoth design and asks his former friend Howard Roark for help. He accepts to design the buildings for the settlement under Keating's name, on the condition that no details are changed in his plans.

Howard Roark now spends a lot of time with Dominique and Gail Wynand. Dominique, who still doesn't love her husband but has got used to living with him, is jealous because Howard and Gail have become such good friends. When the two go on a long journey with Wynand's yacht together, the publisher promises the architect the contract for a long-planned skyscraper, the Wynand Tower, which Wynand wants to be the tallest building in the city and his legacy to the city of New York .

In the meantime, Keating has to struggle with the builders of the estate, who, against his will and in contradiction to his promise to Roark, are pushing through changes to the plans - a number of innovations serving the individual quality of living are being deleted and replaced by the traditional elements of cheap tenements. When Roark sees the first completed building, he reacts calmly on the outside, but has already made a decision on the inside. When Dominique visits him in his office to confess that she still loves him and that she is determined to leave Gail, Howard asks her a favor. In the evening she drives to the construction site to distract the guard. This allows Roark to get to the construction site and blow up the finished building there in order to be arrested immediately afterwards.

In the weeks leading up to the trial, Toohey tries again to turn the public against Roark by preaching about the abandonment of the individual and unconditional submission to the community and by demanding the extermination of a Roark type. Wynand, on the other hand, wants to stand by his convictions for the first time in his life and starts a campaign to defend Roark with his newspaper. Dominique now also wants to stand by Howard, but he refuses to protect her and her husband from popular anger.

Ellworth Toohey, who has since been sacked by Wynand, pressures Keating and tells him that what he really wants is power and the ability to hold down and control the masses. He gets Keating to sign a confession in which the latter admits the authorship of Roark's settlement plans. When the news got around, the editors of the banner wanted to headline too, which Wynand can only barely prevent because Toohey's influence on the editorial team had increased enormously in the meantime despite his absence.

The public is boycotting the banner, but Wynand is determined to keep fighting even as the bulk of reporters resign in protest. But even Dominique, who offers her help, cannot prevent Gail from finally giving in to pressure from the newspaper's supervisory board and the banner joining the prevailing opinion.

In court, where he insists on defending himself, Roark finally makes a fiery plea for individualism and the creative power of the individual. He is then found not guilty by the jury. While Dominique is overjoyed, Gail, who was watching the trial from the back row, leaves the courtroom bitter knowing that he has lost another fight, even if he was forced to in the end.

Roger Enright has since bought the settlement and gives Roark the responsibility to build the settlement as he originally planned. Wynand asks Roark into his office, where he tells him that the banner has ceased appearing and, distant and indifferent, assigns him the job of the Wynand Building. In addition, he did not want to see Roark again. However, the building should radiate the individualism that he himself lacked throughout his life. When Roark left the office, Wynand shoots himself in the head.

Finally, Howard and Dominique marry and together examine the completion of the Wynand Building.

background

The figure of the architect Howard Roark was inspired in this film as well as in the underlying book by Frank Lloyd Wright, whose buildings were partly taken as a model for the models shown on the screen. Wright was a student of Louis Sullivan , whose guiding principle Form Follows Function was slightly modified as a tribute to the dying Henry Cameron.

Wright was originally supposed to be the set designer for the film, but this failed because of his excessive fee demands. So was Edward Carrere committed that in the work of Wright and designs for the Chicago Tribune Tower oriented. One of Roark's buildings, for example, resembles the sober competition entries by Walter Gropius or Bernard Bijvoet , while the traditional buildings by Roark's contemporaries come closer to the winning design for the Tribune high-rise by Raymond Hood .

The evaluation and classification of the architecture represents an essential difference between the novel and the film. While in the novel Roark's material-appropriate and down-to-earth style is clearly set against the cooler European modernism and is intended to illustrate the striving for original architecture, the strict European forms stand for in the film Individuality and are set in contrast to the overloaded designs of Roark's contemporaries, who are compared to a soft adherence to old norms. The projects of Roark's teacher Cameron seem like an anticipation of the brutalism of the 1950s.

reception

The film was shot from July to October 1948 and opened in US theaters in July 1949. The contemporary reviews were rather negative. In addition to the accusation of the wooden representation of Gary Cooper and critical comments on the cast in general, the architecture press in particular rejected the film because of the sometimes unrealizable and too bold designs. The image of the architect drawn here was also too one-sided and the question was asked whether an artist could take the liberty of destroying someone else's property in order to preserve their own integrity.

Frank Lloyd Wright, who still praised the novel and designed a (unrealized) house for the author, distanced himself from the film mainly because of the demolition scene:

- “I don't want anything to do with it. I agree with the thesis that an artist has a right to his work, but here it has gone too far. It gives my philosophy a wrong aftertaste. She wanted me to comment on her book, but I refused. "

Remarks

- Patricia Neal was only 22 years old at the time of filming. The production company gave her the role in the hope of making her a star and therefore gave her preference over established actresses like Bette Davis , Ida Lupino and Barbara Stanwyck .

- Ayn Rand, author of the script and the template, placed a lot of emphasis on the exact implementation of her script, similar to her film character. She negotiated with the producers the full version of the final monologue of the main character. When King Vidor tried to cut the hard-to-understand words, Rand intervened and the speech had to be recorded in full. At six minutes, this is one of the longest monologues in film history.

- The novel was a bestseller at the time and, due to its optimistic tenor, was particularly popular with the American troops during the Second World War . For this a shortened version was published, which however aroused Rand's displeasure because the shortening was carried out without their consent. Even today it is still sold in large numbers.

Reviews

“The film adaptation of an extremely successful bestseller at the time, which is based on the biography of the star architect Frank Lloyd Wright, is a remarkable curiosity in terms of film history: in the middle of a time when Hollywood films are characterized by dark 'film noir' visions she is a fiery plea for individualism and creative integrity that is characterized by optimism. The film's staging is rather bumpy, and the visual symbolism and the pretentious dialogues are very thick. Outstanding - also in its weaknesses, since Wright's constructions were partly leveled - is its equipment: In no other Hollywood film had such an impressive dramaturgical space been allocated to contemporary architecture. "

literature

- Ayn Rand : The Eternal Well . Novel (Original title: The Fountainhead ). German by Harry Kahn . 4th edition. Goldmann, Munich approx. 1993, 940 pages, ISBN 3-442-03700-X

- Dietrich Neumann: The Fountainhead . In the S. (Ed.): Film architecture. From Metropolis to Blade Runner. Exhibition Deutsches Architektur-Museum and Deutsches Filmmuseum 1996. Munich, New York: Prestel 1996, pp. 126 - 133. ISBN 3-7913-1656-7

Web links

- Fountainhead in the Internet Movie Database (English)

Individual evidence

- ^ Business Data for The Fountainhead (1949)

- ↑ Start dates for The Fountainhead (1949)

- ↑ In: The Citizen , 1950. Quoted from: Dietrich Neumann, p. 130.

- ^ Anne C. Heller, Ayn Rand and the World She Made , Doubleday, New York 2009, ISBN 978-0-385-51399-9 . P. 169

- ↑ A man like explosives. In: Lexicon of International Films . Film service , accessed December 28, 2016 .