Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and the sanatoriums

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and the Sanatoriums summarizes Kirchner's stays in sanatoriums , their causes, biographical contexts and artistic results.

Beginning of the story of suffering

Kirchner himself names the experiences of the military in World War I as the beginning of his story of suffering . The first lasting frightening experience came when Kirchner and his partner Erna Schilling returned from Fehmarn to Berlin prematurely because of the outbreak of war in early August 1914 and were arrested for alleged espionage. In order to avoid serving with the infantry, Kirchner reported in 1915 as an "involuntary volunteer" for military service. Despite the personal relief that Hans Fehr , a friend of Emil Nolde's, was able to provide for him, he experienced the training of recruits as traumatic and, with Fehr's help, was initially on leave from military service and, after an attempt to return to the barracks in Halle, was finally dismissed as unfit for service. A work related to this period is the self-portrait as a soldier, which shows him himself in the uniform of the 75 regiment with red epaulets, smoking and with his right hand chopped off. The act of his partner Erna Schindler in the background emphasizes the horrors of the war, its possible mutilations and losses through the contrast and gives an impression of how strongly Kirchner experienced the war, which he himself rejected as capitalist, even if he himself was not a soldier was involved. On the wall are unfinished works that the artist will no longer be able to paint.

The self-portrait as a drinker, which was initially titled The Absinthe Drinker in connection with Picasso's Die Absinththrinker (1901) , refers on the one hand to Kirchner's existing problem of alcohol and drug abuse. The picture was painted before the military era, it also shows that Kirchner was aware of this problem himself. The drinker sits in a pale blue smock with red and green stripes. The bent upper body with the large head, which looks out of the picture in three-quarter profile, is the main focus of the picture. The face, which bears the artist's features, has frozen into a gray-blue, African-looking mask, the eyes “see nothing”. On the heavy table, next to the drinker's face, sits the oversized wine cup that has transformed him. The perspective is shifted.

“It looks as if an earthquake had raged, the red table, big and heavy as a millstone, hangs forward, a blue stool seems to float freely in the cubistically shifted space. The pale colors are reminiscent of the last light that passes in a total solar eclipse. "

In spite of the possibility of concrete interpretation in the context of the painter and his addiction problem, it also reflects the world in a state of war.

Sanatorium stays in Königstein

Kirchner stayed in the sanatorium in Königstein from December 1915 to January 1916, from mid-March to mid-April 1916 and then again from early July to mid-July 1916 . He was motivated to stay by friends who were concerned about his poor health. He himself saw the stays as an active attempt to avoid being drafted to the front. The diagnoses made there by the head of the sanatorium, Oskar Kohnstamm , who had also dealt with the so-called war neuroses , include a “general weakness of the constitution”, a “nervous state of excitement” with insomnia, dependence on veronal , alcohol addiction and a impending addiction to morphine . Anneliese Kohnstamm, the doctor's daughter, wrote in her memoirs: “He seemed to live on cigarettes and veronal. The nightmare of the war and the thought of the front seemed to consume him. "

Despite the health crisis, the years were an artistically creative time. Kirchner was supported in this by Oskar Kohnstamm, who was interested in his work and suggested, among other things, that he would paint the buildings in the sanatorium. Kirchner initially had the idea of creating a ceiling painting in the dining room based on the model of the Sistine Chapel , but this met with resistance. Thereupon Kohnstamm provided him with the somewhat secluded fountain tower, in which Kirchner created a five-part wall painting over an area of 32 m² within six weeks based on drafts that had meanwhile been prepared in Berlin . With his “paradisiacal” scenes and bathing scenes by the sea, the motifs of which were linked to the time on Fehmarn and which can be seen as a longing alternative to the existing war situation, the possibly most important wall painting of German Expressionism was created. In a description by the art historian Max Sauerland it says:

“Kirchner painted murals in a very uncomfortable room through the stairs, in which the task was conceived and carried out with an almost exuberant harmlessness and freshness. There is something indescribably youthful, almost boyish, something quattrocentist in the most beautiful sense of the word, in the style of these sea and bathing pictures, a joy in water and bathing, an immediate closeness to life and at the same time a purely artistic solitude that seems to me to be a perfect achievement in its kind. "

It was irretrievably destroyed in 1938 by National Socialist “iconoclasts”. In addition, a total of eight sketchbooks, drafts for monuments and around 20 oil paintings were created during this time .

Stay in the nerve sanatorium in Berlin-Charlottenburg

After returning to Berlin in December 1916, Kirchner asked for admission to Karl Edel's mental hospital in Berlin-Charlottenburg . The clinic, which was also called the Asylum for the Mentally Ill or the Edelsche Heilanstalt , was also a private clinic, which was probably already run by the sons Max and Paul Edel at that time. Since in the literature only “Dr. Nobody is talking about it, it is therefore unclear which of them made the suspected diagnosis of syphilis , which , if left untreated , can also cause psychological symptoms as neurolues . However, parents and brother brought Kirchner back from the clinic in early 1917. The philosopher friend Eberhard Grisebach , who was married to a daughter of the Spengler couple, had meanwhile successfully campaigned for care by his mother-in-law, Helene Spengler, the wife of the pulmonologist Lucius Spengler in Davos . The focus was on a positive influence of nature and the mountain air, but the move from war Germany to neutral Switzerland may also have played a role. Kirchner therefore accepted the proposal with pleasure and set out for Davos on January 15, 1917. Kirchner himself seems to have used Edel's rather somatic interpretation of his suffering also in the sense of relief. He wrote to Irene Euken on April 8, 1917:

"The staggering in progress and the bad writing, sometimes better and sometimes worse, do not come from veronal poisoning as the doctor in Edel's sanatorium found, but are the consequences of a natural tuberculous brain ulcer."

For Irene Eucken (1863–1941), the wife of Nobel Prize winner Rudolf Eucken , he illustrated the exhibition catalog for her clothes from the embroidery room with woodcuts, despite his poor health, and took care of the success of the catalog, right down to the selection of paper and printing.

Sanatorium stay in Kreuzlingen

In Davos, Kirchner and his nurse moved into a rented hut on the Stafelalp above the town . He hoped to find recovery in the solitude of nature, was artistically productive, but continued to suffer from the fear of being sent to war. This was expressed in various psychosomatic complaints, which he tried to combat with the means already known. The architect friend Henry van de Velde found him on a visit emaciated, feverish, paralyzed with hand paralysis, insecurity while standing and seemingly delusional fears. On his initiative and with his financial support, Kirchner spent ten months at the Bellevue sanatorium in Kreuzlingen in Thurgau from mid-September 1917 , where he was cared for by the psychiatrist and psychoanalyst Ludwig Binswanger .

The private psychiatric sanatorium was characterized by a combination of psycho- and physiotherapeutic , dietetic and milieu therapeutic measures, which were individually tailored to the patient. Kirchner himself positively mentioned electrotherapy , which was very new at this time and could be carried out in Bellevue (not to be confused with electroconvulsive therapy, which was only carried out in psychiatric hospitals from the 1930s ).

Kirchner recovered in this environment to such an extent that he was able to paint again after just three weeks, which was made possible spatially and through the provision of the necessary materials. From March 22 to April 10, 1918, Nele van de Velde stayed at the Bellvue sanatorium and became friends with Kirchner. He portrayed her several times and gave her artistic advice, also with regard to printmaking techniques. She in turn provided him with literature, paints and paper.

He also took care of re-establishing contact with his partner Erna Schilling, who had to wait in the studio in Berlin for an exit permit. She wrote about her first visit to Bellevue: "For the first time, he found in the doctors of the house and also in his personal care people who support him in every way and treat him in accordance with his individuality." Friends who visit him reported one astonishing quick improvement of his health and the return of his creativity. When the visitors left again, they continued to show severe depressive states, which were also expressed in a strongly self-critical attitude towards the painted pictures: “I am now out of luck with my pictures. They look a little raw. It is very difficult to form something whole out of the enormous variety of shapes and colors. ”While he was able to formulate his thoughts on art more and more clearly during this time, the symptoms of paralysis in his hands repeatedly bothered him in practical artistic work. The fear expressed in the self-portrait as a soldier caught up with him in a weakened form as a psychogenic symptom.

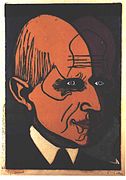

In the sanatorium there was a stimulating spiritual and cultural life - also through the visitors - which Kirchner gratefully accepted. The encounters were reflected in his works from 1917/18. The portraits of his loyal friends and supporters van der Velde and Botho Graef hung over his bed. Ludwig Binswanger became a friend to him, as did his mother-in-law, Marie-Luise, née Meyer-Wolde, who took great care of him and was a stimulating conversationalist and who portrayed Kirchner (woodcut Dube 315 / II). The biologist Julius Schaxel , who also frequented Bellevue and was portrayed by Kirchner, described the artist's morbid, often maddening distrust as well as his impressive artistic energy. Kirchner himself also indicated this limit when he later wrote about the woodcuts made at Bellevue:

“They came about during a very difficult time in which I received the endless suggestions from Dr. Ludwig [Binswanger] had to unite with the transformation of his own life. Very handicapped by the physical suffering in my work, I sometimes swayed by a hair's breadth to the limit where communication with the others ends. "

An exhibition of his works in Zurich in March 1918 caused him great excitement; he traveled there himself to check the hanging and returned calmly. With the help of a carer, he put together a collection of over 250 sheets, which he had sent to Jena as a foundation for Botho Graef. The treatment went well overall and Kirchner returned to Davos with a new courage to live, also in the certainty that he would be able to return to Kreuzlingen again next autumn. On July 9, 1918, Kirchner reported from the residents' registration office in Kreuzlingen and traveled with Erna and the caretaker Brüllmann to Davos on the Stafelalp, where he was warmly welcomed by the residents. In September 1918 Erna traveled to Kreuzlingen without him to pick up the works that had remained there. Kirchner finally concluded his treatment there and thanked Ludwig and Otto Binswanger with the gift of a cycle of woodcuts, illustrations for the "Triumph of Love" by Francesco Petrarca . Ludwig Binswanger visited the Kirchners on the occasion of a stay in Davos on the Stafelalp and was able to convince himself of the improvement in his health.

Davos

In Davos, Kirchner received medical care in his recurring ailments until his death by Frédéric Bauer, who was the chief physician of the Davos park sanatorium. He was not only a doctor, but also a friend and confidante and at the same time his collector. Over the years he acquired more than 400 works by Kirchner.

For further information on Kirchner's life and death, see the main article Ernst Ludwig Kircher: Davoser Zeit .

Pictures (selection)

Literature (selection)

- Albert Schoop: Ernst Ludwig Kirchner in Thurgau. The 10 months in Kreuzlingen 1917–1918. Kornfeld, Bern 1992, ISBN 3-85773-028-5 ( snippet view in the Google book search).

- Anton Henze : Ernst Ludwig Kirchner. Life and work. Belser Verlag, Stuttgart / Zurich 1980, ISBN 3-7630-1693-7 .

Individual evidence

- ^ Albert Schoop: Ernst Ludwig Kirchner in Thurgau. The 10 months in Kreuzlingen 1917–1918. Kornfeld, Bern 1992, ISBN 3-85773-028-5 , p. 9.

- ↑ Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Königstein and Julius Hembus. Edited by Christian Goldberg. Exhibition cat. Hellhof Gallery, Kronberg im Taunus. Ed. Goldberg, Stade 2003, ISBN 3-00-011306-1 , p. 10 f. (Catalog for the exhibition on the occasion of the 100th birthday of Julius Hembus in the Hellhof Gallery, Kronberg im Taunus, April 27 to June 1, 2003).

- ^ A b Anton Henze: Ernst Ludwig Kirchner. Life and work. Belser Verlag, Stuttgart / Zurich 1980, ISBN 3-7630-1693-7 , p. 45.

- ^ Anton Henze: Ernst Ludwig Kirchner. Life and work. Belser Verlag, Stuttgart / Zurich 1980, ISBN 3-7630-1693-7 , p. 54.

- ↑ Homepage of the Kirchnermuseum Davos . In: kirchnermuseum.ch, accessed on January 26, 2017.

- ^ EH Kirchner: Documents, photos, writings, letters. Collected and selected by Karlheinz Gabler, published by the Museum der Stadt Aschaffenburg, Aschaffenburg 1980, p. 162

- ^ Anton Henze: Ernst Ludwig Kirchner. Life and work. Belser Verlag, Stuttgart / Zurich 1980, ISBN 3-7630-1693-7 , pp. 46 and 83.

- ^ Roland Scott: Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Königstein and Julius Hembus. In: Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Königstein and Julius Hembus. Edited by Christian Goldberg. Exhibition cat. Hellhof Gallery, Kronberg im Taunus. Ed. Goldberg, Stade 2003, ISBN 3-00-011306-1 , pp. 8-13 (catalog for the exhibition on the occasion of the 100th birthday of Julius Hembus in the Hellhof gallery, Kronberg im Taunus, April 27 to June 1, 2003) .

- ^ Anton Henze: Ernst Ludwig Kirchner. Life and work. Belser Verlag, Stuttgart / Zurich 1980, ISBN 3-7630-1693-7 , p. 46 f.

- ^ Norbert Wolf : Ernst Ludwig Kirchner (1880–1939). At the Edge of the Abyss of Time. Taschen, Köln / London 2003, ISBN 3-8228-2123-3 , p. 74 (English).

- ^ Volker Wahl : The expressionist painter Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and Irene Eucken 's embroidery room in Jena . With an edition of Kirchner's letters to Irene Eucken from 1916 to 1920. In: The big city. The cultural-historical archive of Weimar-Jena. Edited in connection with the archive of the Bauhaus University Weimar. Vopelius, Jena, 2 (2009), issue 4, ISSN 1865-3111 , pp. 308–334, ( PDF; 435 kB ).

- ^ Anton Henze: Ernst Ludwig Kirchner. Life and work. Belser Verlag, Stuttgart / Zurich 1980, ISBN 3-7630-1693-7 , p. 47.

- ^ Albert Schoop: Ernst Ludwig Kirchner in Thurgau. The 10 months in Kreuzlingen 1917–1918. Kornfeld, Bern 1992, ISBN 3-85773-028-5 , p. 14 ff.

- ^ Albert Schoop: Ernst Ludwig Kirchner in Thurgau. The 10 months in Kreuzlingen 1917–1918. Kornfeld, Bern 1992, ISBN 3-85773-028-5 , pp. 21 and 28 f.

- ^ Julia Susanne Gnann: Binswangers Kuranstalt Bellevue 1906−1910. Dissertation, Tübingen 2006, DNB 982382871 , pp. 88–91 ( PDF; 1.54 MB ).

- ^ Albert Schoop: Ernst Ludwig Kirchner in Thurgau. The 10 months in Kreuzlingen 1917–1918. Kornfeld, Bern 1992, ISBN 3-85773-028-5 , p. 29

- ^ Albert Schoop: Ernst Ludwig Kirchner in Thurgau. The 10 months in Kreuzlingen 1917–1918. Kornfeld, Bern 1992, ISBN 3-85773-028-5 , p. 30

- ^ Albert Schoop: Ernst Ludwig Kirchner in Thurgau. The 10 months in Kreuzlingen 1917–1918. Kornfeld, Bern 1992, ISBN 3-85773-028-5 , p. 39.

- ^ Albert Schoop: Ernst Ludwig Kirchner in Thurgau. The 10 months in Kreuzlingen 1917–1918. Kornfeld, Bern 1992, ISBN 3-85773-028-5 , p. 34.