Gankogui

Gankogui ( Ewe , plural gankoguiwo ), also gankoqui , Ewe and Fon gakpavi , gakpevi , is a double-hand bell without a clapper, which is used in the music of the Ewe in the south of Ghana and the Fon in Togo and Benin as a percussion instrument . The two different sized metal bells of the surcharge idiophons are struck with a wooden stick. In the big drum orchestra, the double bells form the indispensable rhythmic framework, and in certain rituals they have a magical meaning.

Design and distribution

Ghanaian idiophones

The first summary of the spread of bells over Africa south of the Sahara gave Bernhard Anchorman (1901). In Ghana, metal bells are used with and without a clapper. There are two types of single bells without a clapper: One is in the form of a long, narrow funnel and is held at the top between the fingers. The Ewe in Togo call them gakokwe. The other idiophones consist of a boat-shaped curved segment of a circle , which is held in the palm of the hand like a blossoming flower without touching the side surfaces. The latter instrument made of forged iron is called by the Ewe atoke (or toke ), it produces a certain pitch like the gankogui and is used, among other things, for the background rhythm in the Hatsyiatsya songs and the Gahu dances. The Latin American cowbell has a closed shape like the gakokwe and rests in the hand like an atoke .

In Ghana there are also spherical or conical bells that are worn on the middle finger and attached to the thumb with a ring. Iron forks with cymbals attached to them are known in northern Ghana . Pumpkin rattles , batons and calabashes , which are turned upside down on the ground and hit with the fingers in the north, are used for rhythmic fine- tuning . In the south, calabashes are used as water drums , the Akan beat them with their hands, the Ewe with sticks.

Simple bells, iron forks, cymbals and rattles from the Gold Coast are shown next to drums and a raft zither, which is not clearly shown, on an anonymous copper engraving from the 18th century under the heading “Musical instruments on the Gold Coast”. The illustrations were made from the notes of Jean Barbot (around 1670–1720), who saw the instruments near what is now the capital, Accra .

Double bells

Simple, forged bells were already known in a large area between West Africa and Zimbabwe before 800 AD ; Between the 11th century and the middle of the 15th century, the first double bells can be found in central Africa. They consist of separately manufactured bells that can be connected to one another in two different ways: The bells of the Dagomba and Mamprusi in northern Ghana are connected to one another via a semicircular bracket . In Nigeria and the Congo , these double bells are regionally called ngonge, ngongi, ngunga or engongui . The Lunda in the south of the Congo call them lubemb . With the black slaves , African music also came to Brazil , where the double bell agogô is played in dance music.

In contrast, with the stem double bells, which also include the gankogui , both parts taper to form a stem on which they are welded together at an acute angle. Stem double bells were classified as "Guinea type" and are also common among the neighboring peoples of the Ewe. The Ife in Atakpamé call them ango , the Mahi in the south of Benin ganvikpan . The Edo (Bini) in southwestern Nigeria use both types of double bells: they call the iron bow bells egogo eregbeva (from egogo - "bell", egbe - "body" and eva - "two"), 20 to 30 centimeters long, only used ritually Stem bells made of brass or bronze are simply called egogo , like the simple iron bells up to 150 centimeters in size .

The distribution area of the double bells extends from Mali in the west, where the Dogon worship the gangana as a ritual instrument, through Nigeria and the Congo to Zimbabwe and Angola (bow-shaped ngongo ). Some examples of double bells could also be found for the Central African Republic between the northern and southern regions, including Gerhard Kubik photographed the large standing double bell ( tatum ) of a chief on the Sangha River in 1964 , which was probably forged around the turn of the 20th century was. The valley of the Ubangi and Congo rivers forms a gap between the areas of distribution of the double bell in west-central and southern Africa .

Four of the 295 Benin bronzes of the Kingdom of Benin cast in the mid-16th to mid-17th centuries and containing musical instruments - artistic groups of figures on rectangular relief plates - show double bells. The palace guards of the Fon in the Kingdom of Dahomey were called panigan after the name of the double bells ( panigan , also kpanlingan ) that they struck while ritualized flawlessly three times a day during the time of the annual festival ( huetanu ) and every morning during the rest of the year Had to declaim the text.

The obvious cultural significance of the double bells led Erich Moritz von Hornbostel to incorporate the clapless African bells into his cultural theory at the beginning of the 20th century and to suspect an Indonesian origin. In fact, there is no formal counterpart to the double bells in Southeast Asia as suggested by Arthur Morris Jones . Only the boat-shaped atoke and similar slit bells in Gabon have a resemblance to the kemanak of Javanese gamelan , and both are usually played in pairs.

Ghanaian double bells

The gankogui are forged from sheet iron and hammered. One bell is significantly larger than the other, so there are two playable tones about a third apart . In the name of the single bell, gakokwe (also gakoko ), ga stands for “metal” and ko for an onomatopoeic syllable that repeatedly reproduces the attack tone. Gankogui could contain kogo , "side", that is, refer to a bell that is struck on the side. The word gakpavi for the double bell is made up of ga , again “metal”, kpa , “to carry on your back” and vi , “child”. The different sizes of the bells led to the classification as "mother and child type".

According to a common production method, scrap pipes are made to glow on a forge . As soon as the pipe glows, the blacksmith knocks it out until a rectangular plate is formed. The plate is put into the fire again until it burns red and is then knocked out thinly. After reheating, two corners are bent inwards and folded over each other. A second plate is created in the same way. A template made of hardwood is placed between the two panels, the blacksmith can now shape the panels by hitting them from all sides and forging them together at the edges. Meanwhile, the wood inside will inevitably start to burn. The corners that are bent together at the beginning are knocked out to form the handle. A second bell made in the same way is welded to the handle of the first one. A small eyelet at the end of the handle is used to attach a cord.

How to play and use

The player holds the gankogui by the stick in his left hand and strikes with a wooden stick in his right hand. The instrument is played standing or, more appropriately, seated. If the seated player places the gankogui on his thigh immediately after the attack, he can dampen the echo. The big bell also rests on his leg when he strikes the small bell with the stick from his wrist.

Ewe music consists essentially of percussion instruments, which include several barrel drums of different sizes (the largest: atsimevu, supporting drums: the low sogo, the middle kidi and the high kagan (u) ), the vascular rattle axatse and bells. The smallest single-headed barrel drum kloboto (or klodzie ) is reserved for special dances. The entire drum orchestra accompanying all dances consists of the idiophone group in the background, the rhythm drummers and, as a third musical area, the singing combined with clapping of hands. The standard work by Arthur Morris Jones, published in 1959, made the music of the Ewe the classic model of West African drum music for many years and, according to the book title, occasionally also at the core of African music in general. To date, numerous experts have dealt with the rhythmic structures of double bells and drums.

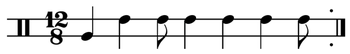

The task of the double bell is to specify the basic beat and further divisions of the bar and to provide a time orientation for the other, polyrhythmic orchestral musicians during the entire performance . In this respect their function corresponds to that of a metronome . The training of the gankogui player must be carried out accordingly carefully . It does not strike the even cycle times, but patterns that consist of eight to twelve beats (pulses) and are constantly repeated. In the background area there is the axatse rattle , which duplicates the bell with its downward strikes and fills the time in between with its upward strikes. This rhythmic basis is for a probably early 1960s by Ghanaian ethnomusicologist JH Kwabena Nketia introduced term time-line pattern called. Accordingly, the rhythmic, dull drum beats are distributed asymmetrically over the underlying, regular sequence of elementary pulses of the metallic-bright sounding double bells. In relation to the gankogui , the bell pattern is also used. The standard pattern with twelve pulses for a bell is:

As syllables: kong - kong - ko - kong - kong - kong - ko

Up to 16 gankoguiwo appear in the music that accompanies the Hatsyiatsya songs, which are sung at the beginning of certain entertainment dances . Popular Ewe dances are listed with every circumstance Agbadza , entertainment dance Gahu and former warrior dance Atsi Agbekor . The Agbadza dance begins with Hatsyiatsya songs, which are followed by the specific dance songs.

Four to six gankoguiwo are common in funeral processions . The traditional funeral dance is called Nyayito after the association of mostly elderly people that organizes it. These are loosely grouped around the two heads of the dance association, the song composer ( Hesino ) and the master drummer ( Azaguno ). While the songs and dances of other fraternities are regarded as their own property and may only be performed by their respective members, every participant in Nyayito dances is allowed to sing the melodies of the fraternity and to play certain instruments such as the gankogui , even those otherwise great atsimevu reserved for the master drummer . The Nyayito Orchestra includes the entire list of the drums and idiophones already listed.

Yeve (or Tohono ) is the cult of the thunder god Adzogbo among the Ewe, who is related to the thunder god Shango of the Yoruba and Xevieso of Benin . Whose cult is secret, by the members of one is initiation and learning requires a special liturgical language. In addition, they have to buy expensive items for the ceremonies. A major part of the cult consists of dances that are performed on a dance floor in front of the cult house. The seven Yeve dances are accompanied by the typical drum orchestra.

Music groups perform in Accra today that combine traditional musical styles and instruments of the various ethnic groups with new compositions and present them in concert events. The result is a multi-ethnic music as it is cultivated in the National Dance Company . In this way the xylophone gyil of the Dagara and Lobi in the north of the country can meet with the deep-sounding box-shaped drum gome and the barrel drum kpanlogo of the Ga on the coast with the bamboo flute atenteben from the center with the bell gankogui and the rattle axatse of the Ewe.

Within their area of distribution in West and Central Africa, iron bells such as metal trumpets and kettle drums (as examples kakaki or naqqara among the Hausa ) belonged to the insignia of the chief's dignity. There they were occasionally beaten by women. As with the Ewe, iron bells also play a role in secret societies with other peoples, where they protect against evil spirits, as well as in circumcision celebrations and funeral processions. On the southern and northern edge of the Sahara, metal rattles ( qarqaba ) take over this function in the popular religious rituals of Muslim societies .

literature

- Gerhard Kubik : West Africa. Music history in pictures. Volume 1: Ethnic Music. Delivery 11. VEB Deutscher Verlag für Musik, Leipzig 1989, p. 144

- Arthur Morris Jones : Studies in African Music. Volume 1. Oxford University Press, London 1959, pp. 51-53

- Arthur Morris Jones: Africa and Indonesia: The Evidence of the Xylophone and Other Musical and Cultural Factors: With an Additional Chapter - More Evidence on Africa and Indonesia. (Asian Studies) EJ Brill, Leiden 1964, ISBN 978-90-04-02623-0 , pp. 161-167

Web links

- The Gankoqui . Motherland Music

- Gankogui. Wesleyan University

Individual evidence

- ^ Bernhard Ankermann : The African musical instruments . (Inaugural dissertation to obtain a doctorate from the Philosophical Faculty of the University of Leipzig) Haack, Berlin 1901, pp. 63–68 ( archive.org )

- ↑ Toke (aka Atoke) . ( Memento of May 12, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) Motherland Music

- ↑ German edition: General history of journeys on water and land or a collection of all travel descriptions, which have been published in different languages by all peoples up to itzo, and make a complete understanding of the modern description of the earth and history. Volume 1–21, Leipzig 1747–1774, plate 14 before p. 158 (illustrated by Kubik, p. 149)

- ↑ Jos Gansemann, Barbara Schmidt-Wrenger: Central Africa. Volume 1: Ethnic Music. Delivery 9. VEB Deutscher Verlag für Musik, Leipzig 1982, p. 40

- ^ Gerhard Kubik, 1989, p. 144

- ^ Eno Belinga: The Traditional Music of West Africa: Types, Styles and Influences. (PDF) UNESCO, Paris 1970, p. 2

- ^ Åke Norborg: Musical instruments of the Bini in southwest Nigeria. In: Erich Stockmann (Ed.): Music cultures in Africa . Verlag Neue Musik, Berlin 1987, pp. 200f

- ↑ Gerhard Kubik: To understand African music. Lit, Vienna 2004, p. 128, fig. 40

- ↑ Jan Vansina : The Bells of Kings. In: The Journal of African History, Volume 10, No. 2, 1969, pp. 187-197, here p. 191

- ^ Philip JC Dark, Matthew Hill: Musical Instruments on Benin Plaques. In: Klaus P. Wachsmann (Ed.): Essays on Music and History in Africa. Northwestern University Press, Evanstone 1971, p. 72

- ^ Gilbert Rouget: Court Songs and Traditional History in the Ancient Kingdoms of Porto-Novo and Abomey. In: Klaus P. Wachsmann (Ed.): Essays on Music and History in Africa. Northwestern University Press, Evanstone 1971, p. 50

- ↑ Arthur Morris Jones, 1964, p. 164 f.

- ^ Jaap Kunst : The origin of the kemanak . In: Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde 116, No. 2. Leiden 1960, pp. 263-269, here p. 267

- ^ Roger Blench: Evidence for the Indonesian Origins of Certain Elements of African Culture: A Review, with Special Reference to the Arguments of AM Jones. In: African Music , Vol. 6, No. 2. International Library of African Music, 1982, pp. 81-93, here p. 89; Arthur Morris Jones, 1964: on atoke pp. 157-161

- ^ Gerhard Kubik, 1989, p. 144

- ^ "The norm of African music is the full ensemble of the dance: all other forms of music are secondary." (Arthur Morris Jones: Studies in African Music, p. 51)

- ↑ Francisco Gómez Martín, Perouz Taslakian, Godfried Toussiant: Interlocking and Euklidean rhythms. In: Journal of Mathematics and Music , Volume 3, No. 1, March 2009, pp. 15-30; here p. 17: Notation interlocking rhythm from gankogui, sogo, kidi and kaganu

- ↑ Arthur Morris Jones, 1959, pp. 51-53

- ^ Daniel Mark Tones: Elements of Ewe Music in the Music of Steve Reich. (PDF) University of British Columbia, March 2007, pp. 12-14

- ↑ Gankogui. dancedrummer.com (audio sample)

- ↑ Arthur Morris Jones, 1959, pp. 72-75

- ↑ Alexander Akorlie Agordoh: African Music: Traditional and Contemporary. Nova Science Publishers, New York 2006, pp. 42-44

- ↑ Jonno Boyer-Dry: Transforming Traditional Music in the Midst of Contemporary Change: The Survival of Cultural Troupes in Accra, Ghana. (BA Thesis) Wesleyan University, April 2008, pp. 16, 18