Money creation

The creation of money is the creation of new money . Book or deposit money is generated by private , cooperative or public commercial banks for their customers when granting loans or purchasing assets . Cash , on the other hand, as part of the monetary base (also called central bank money ) is initially created by a central bank for the commercial banks in similar processes. Cash only comes into public circulation if existing book money is withdrawn by customers of a commercial bank at the counter or at an ATM, i.e. converted into cash.

Book money creation precedes the creation of central bank money. The amount of book money exceeds the amount of central bank money by about ten times.

Creation of the monetary base by the central bank

In contrast to other companies and households, commercial banks maintain accounts with the central bank. They use the funds in these accounts to make payments among themselves. Furthermore, the credit balances in these accounts can be exchanged for cash ( banknotes or coins ) at any time by the commercial banks if their customers or they themselves need cash. The balances of the commercial banks at the central bank together with the cash form the monetary base, also called central bank money or reserves.

The central bank can create central bank money by lending to commercial banks at the current key interest rate and against the provision of appropriate collateral . As part of its open market policy , it can also purchase securities or other assets and grant credit in return. In both cases, commercial banks receive central bank money in their accounts with the central bank.

If commercial banks repay their loans at the central bank or if central banks sell previously acquired securities, central bank money is destroyed. Central bank money can be thought of as a claim against the central bank that disappears as soon as it returns to it. The monetary base is recorded on the liabilities side of the central bank's balance sheet.

Use of the monetary base

As soon as commercial banks create book money as described below, they need central bank money for a number of reasons:

- You must currently hold 1% of the book money generated as a minimum reserve at the European Central Bank as a balance.

- Your customers can exchange their book money for cash at any time, so the commercial bank must first exchange existing central bank balances for cash in order to be able to meet the wishes of their customers. This is currently done with around 10% of book money ( M3 money supply in the Eurosystem ).

- If a customer transfers his book money to a book money account at another bank, the commercial bank of the receiving customer demands central bank money in return ( settlement ) from the bank of the sending customer, unless it grants it an interbank loan. Since transactions between banks often take place e.g. B. cancel by transfers in the opposite direction at the end of the day ( clearing ) and indeed interbank loans are used for the remaining balance , the need for central bank money for this purpose is rather low. If all commercial banks and their customers behave similarly, one speaks of lending in lockstep . In the extreme case, no interbank balances arise at all.

Control of the monetary base

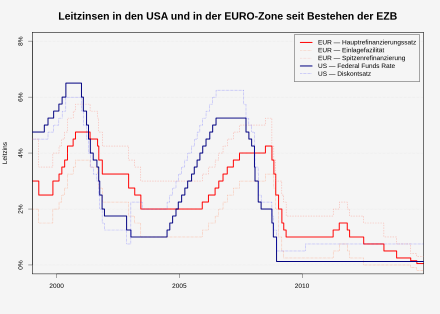

In times of conventional monetary policy, the central bank indirectly influences the monetary base by raising or lowering the key interest rates that commercial banks receive or pay on their balances or their loans at the central bank. As a rule, it then satisfies the entire demand for central bank money on the terms set. In times of economic crisis, however, there may be considerably more central bank money in circulation than for the reasons mentioned, if the central bank considers this to be sensible for its monetary policy goals and buys securities on a large scale ( quantitative easing ).

The amount of cash as part of the monetary base depends on the cash needs of the non-banks, i.e. their withdrawals. It is therefore not influenced by the central bank. The more cashless payment transactions are used, the less cash is required.

Importance of the monetary base

The central bank money stock is usually small compared to the money stock M3 in public circulation and is not in a fixed relationship to it (see graphic opposite, money stock is explained below under deposit creation by commercial banks ). Apart from the cash in customer possession, the monetary base is also not part of the money supply M3, since central bank balances only serve as means of payment between banks. Nevertheless, changes in key interest rates have a significant impact on the economy as a whole. So they put z. B. upper and lower limits for the money market interest rates ( EURIBOR or LIBOR ), at which commercial banks grant each other loans, since an interbank loan could be substituted by the transfer of central bank money ( see the section on interest rates below). Via the medium to long-term outlooks of the central banks and other transmission mechanisms, changes in key interest rates also affect savings and loan rates for longer periods and other variables in the economy such as wage levels, inflation or economic growth. The European Central Bank orients its monetary policy primarily to its inflation target, other central banks also to growth or employment targets.

Seigniorage and coin winning

A central bank usually generates a profit, also known as seigniorage , through interest or distributions on securities it holds . This profit is retained as a fluctuation reserve or goes to the state. The central bank does not refer to the difference between production costs and the nominal value of banknotes as seigniorage, since it would withdraw cash at any time and place it on the liabilities side of its balance sheet.

Unlike banknotes, coins are minted by the state and sold to the central bank at face value. They are then put into circulation as part of the cash, analogous to the banknotes. The state receives a coin profit, i.e. the difference between nominal value and production costs.

Deposit money creation by commercial banks

The money that bank customers keep in current accounts and use daily for transfers , direct debits or cash withdrawals or keep in savings accounts is so-called book money or bank money. The cash does not belong to the deposit money.

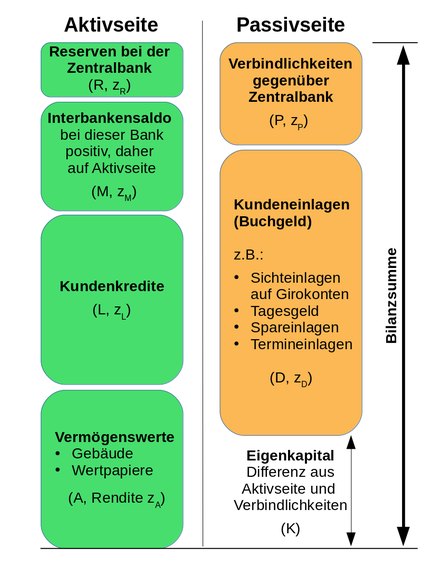

If commercial banks provide a customer with a loan , they generate deposit money in this customer's current account. In the adjacent schematic representation of a bank balance sheet, this corresponds to the simultaneous increase in customer loans (L) on the assets side and customer deposits (D) on the liabilities side, i.e. a balance sheet extension . Credit agreements with customers appear as claims for repayment on the assets side of a bank balance sheet. The resulting book money on the liabilities side is a claim against the generating commercial bank. Will it e.g. B. when repaying a loan, transferred back to the bank, this claim against the bank cancels itself and the money is thus destroyed (balance sheet shortening).

If commercial banks buy assets, such as skyscrapers, data centers or securities, from their own customers, they pay with the deposit money they have generated, which they make available to the seller in an existing checking account. In the illustration opposite, this corresponds to a simultaneous enlargement of positions A and D, thus also an extension of the balance sheet. Of course, a commercial bank can also add a seller as a new customer for payment by setting up a new account with the amount to be paid. In any case, deposit arises in the banking system on the seller's account when a commercial bank buys an asset from him, even if he is not a customer of the bank. If a commercial bank sells assets from its portfolio, the purchase price debits the buyer's credit and the book money is destroyed again.

Deposit money creation is a booking act. In particular, commercial banks do not need to have previously owned this new money (D) as equity , not have it held as customer deposits on their balance sheet, or borrow from the central bank or other commercial banks. However, as a result of this creation of deposit money, you must comply with the minimum reserve requirements of the central bank and meet the minimum capital requirements for credit risks .

Furthermore, competition with other banks results in interest costs ( ) for the deposit money generated for the commercial banks , as will be explained below. In addition, the secure administration of customer accounts in branches and data centers generates costs.

Only banks' liabilities to non-banks and cash at non-banks are included in the money stocks M1, M2 and M3. Liabilities between banks, such as interbank balances on the liabilities side, are not included. Non-banks are households, companies that are not banks or the state. The different amounts of money thus measure the deposit (D) of different retention periods plus the amount of cash in circulation. With a longer commitment period, the character of the deposit disappears more and more as a means of payment that is available in liquid form, so the amount of money depends on its definition. These definitions differ between the currency areas.

Relation to the money creation multiplier

Many outdated textbooks explain that commercial banks act as financial intermediaries and lend out central bank money or customer deposits. In doing so, you increase the initially generated and contingent monetary base as deposit money by means of a money creation multiplier depending on the minimum reserve and cash holdings. In view of the actual monetary policy of the central banks, the timing of the maintenance of minimum reserves and the observed limitation of money creation due to a lack of credit demand, this notion is not tenable. She was u. a. rejected by the Bank of England and the Deutsche Bundesbank at various points. In particular, the monetary base for the cash requirement, the minimum reserve and the settlement between the banks is only created as a result of the creation of deposit money. Also, the monetary base is usually not quota, but commercial banks can procure as much at the given key interest rate as they need for the purposes described (interest rate control by the central banks). On top of that, as indicated in the next section, some central banks do not require a minimum reserve at all.

Reserve requirement

In the adjacent balance sheet, the minimum reserve requirement means that the reserves at the central bank (R) must amount to at least 1% of customer deposits (D). If this is not the case, the bank can exchange a small part of its assets (mostly securities) in the open market transactions at the central bank for further reserves. This may also happen after a loan has been granted or assets have been purchased within a so-called minimum reserve period, and thus the minimum reserve requirement does not limit the creation of deposit money.

If, for example, a commercial bank buys a high-rise building with 100 floors for EUR 100 million it has generated itself, it can then swap 1 floor for EUR 1 million in central bank money in a repurchase agreement with the central bank ( repurchase agreement at the key interest rate ) and thus meet the minimum reserve requirement, provided that High-rise floors represent eligible collateral. If the bank expands the repurchase agreement by another floor, it also fulfills the minimum reserve requirement, e.g. B. to create new deposit money of EUR 100 million for loans. The European Central Bank pays interest on the minimum reserve at the base rate ( ), so that the commercial banks only incur administrative costs due to the minimum reserve requirement.

No minimum reserve is currently required in the euro area for customer deposits with a term or notice period of more than two years. Central banks of some countries, such as Australia, Canada, England or Sweden, do not require a minimum reserve.

Capital requirement

According to the Capital Adequacy Ordinance (CRR) according to Basel III , a bank must reserve up to 8% equity (position K) for the positions on the assets side, depending on the probability of default. Equity is calculated as the difference between assets and liabilities on the liabilities side. The probability of default on assets is mostly assessed by rating agencies . This requirement can restrict the generation of funds against risk positions to 12.5 times the equity. However, if the bank buys safe government bonds, no equity capital is required.

Example of equity ratios based on 8% according to Basel III depending on the risk level ( rating ) of the assets:

| Credit rating according to CRR | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4th | 5 | 6th | 7th |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rating code Standard & Poor’s | AAA to AA- | A + to A- | BBB + to BBB- | BB + to BB- | B + to B- | CCC + and below |

unjudged |

| Moody's rating code | Aaa to Aa3 | A1 to A3 | Baa1 to Baa3 | Ba1 to Ba3 | B1 to B3 | Caa1 and below |

unjudged |

| Risk weighting of the 8% | 0% | 20% | 50% | 100% | 100% | 150% | 100% |

| Equity required | 0% | 1.6% | 4% | 8th % | 8th % | 12% | 8th % |

A bank can raise new equity by e.g. B. New shares issued . These stocks are bought with book money that is ultimately generated by the banking system itself but belongs to the buyers. In the medium term, if there is enough trust in the bank on the part of the capital market, the money supply can be expanded. As described above, every new equity can be used as a basis for a multiple of risky assets and thus also new book money on the liabilities side.

Cash withdrawal and transfer

If a customer withdraws part of his deposits (D) from his current account, position D is reduced for the bank on the liabilities side. On the assets side, it exchanges central bank reserves (R) at the central bank for banknotes and coins and hands them to the customer, e.g. . B. from an ATM. This also reduces R by the amount withdrawn.

If a commercial bank threatens to fall below the required minimum reserve as a result of the process described, it must enter into new liabilities to the central bank (P) at the key interest rate in order to increase its reserves (R) in return. The commercial banks pay the key interest rate to the central bank for all the cash in circulation. The central bank, in turn, regularly transfers its profits to the state as described above. Cash is associated with neither positive nor negative interest for the user. However, it is subject to inflation.

If a customer transfers part of his deposits to a customer of another bank, position D on the liabilities side is also reduced for the transferring bank. The receiving customer's bank will only grant them a new liability (deposit) on their liabilities side, provided that the transferring bank transfers reserves (R) in the same amount to their account at the central bank (see picture above). Alternatively, it can grant the transferring bank an interbank loan. For the transferring bank, either the position R or the interbank balance M decreases on the assets side. For the bank of the receiving customer, the opposite applies. The interbank balance can of course also turn negative and then appears on the liabilities side of the bank balance sheet.

Consideration of Interest

: 1 week (green), 3 months (blue), 1 year (red)

If you look at the bookings, as happened above, mostly without interest , risks or agreements on term and collateral , it is not apparent which incentives and restrictions are behind them. Transactions with the central bank that are carried out at the key interest rate usually have a term of a few days. This section describes how this short-term interest is passed on to the money market, as well as to deposit and lending rates. Additional influences on longer-term financial products are indicated in the next section.

The key interest rates set by the central bank are shown in the simplified bank balance sheet . As can be seen in the adjacent graph, these effectively control the interbank interest rates ( EURIBOR or LIBOR ) through the possibility of direct substitution . It applies approximately

Now it is profitable for every commercial bank to induce customers of other banks to transfer their deposits (D) to it with an interest rate . This naturally incurs costs for the bank (additional D with interest rate ) on the liabilities side. However, with the transfer, a claim against the bank of the transferring customer arises at the same time, i.e. a positive interbank balance (additional M with interest rate ) on the assets side. Obviously, this business is worthwhile for a bank as long as it stays smaller than the costs of managing the accounts. A deposit rate should therefore be set at banks that are in competition with one another

In an environment of competing commercial banks, the key interest rates are passed on via the interbank rates to the short-term savings and deposit rates (e.g. overnight money ). This pass-through is by no means obvious. It is often assumed that the banks are only burdened with interest on the necessary reserves when they create money. This overlooks the fact that the declared arbitrage transactions are also controlled by the key interest rates. Most of the interest, even on short-term liabilities, is not paid by the banking system to the central bank, but to deposit customers.

In the simplified bank balance sheet, however, only one interest rate is given for all customer deposits, although very different items are summarized there. Thus, contrary to the theory of the passing on of interest, you usually get no interest for deposits in a current account, but you do get interest for overnight money. Obviously, the decisive factor for a bank is whether the customer can be expected to emphasize the function of money as a means of payment or whether it is used as a store of value for the best interest rates. It is unlikely that bank customers would regularly expect employers, landlords and insurance companies to have new bank details just to get higher interest rates. This advantage gives banks an incentive to promote cashless payments, because if their customers use cash, they pay the key interest rate for its procurement.

With increased deposit rates , it is of course not advisable for a bank to offer loans at lower interest rates or to buy assets with a lower rate of return than . The reason is that, as described above, with the granted loans (L) or acquired assets (A) on the assets side, customer deposits (D) are granted on the liabilities side. In addition, the bank must be compensated for the credit default risk (see below). There are administrative costs for loans too, and ultimately the bank also wants to make a profit, so is

The bank can also generate the additional book money (D), which makes the interest payment on deposits necessary, by means of a booking act. This reduces the remaining equity (K). Customer deposits (D) are destroyed by interest payments from customers and the bank's equity increases. Interest rate critics complain that the created book money is not enough for repayment and interest. However, the difference between the interest charged by banks and the interest paid by banks can (for example ) be serviced by future further money creation in the event of economic growth. If the growth is insufficient, loans will fail (see below). Building on this, there is a discussion as to whether economic growth necessarily leads to interest or, conversely, whether interest leads to growth compulsion.

In economics, the so-called interest rate pass-through as part of the aforementioned transmission mechanisms is the subject of research. The adjustment of deposit and lending rates to changed key interest rates works faster and more completely in some countries of the European Monetary Union than in others.

Strictly speaking, the reserves of the commercial banks have three different interest rates: the minimum reserve bears interest at the main refinancing rate, excess reserves with the deposit rate and any cash held by banks can of course not bring any interest.

In German-speaking countries, the liabilities arising from the granting of a loan are often mentioned on the liabilities side of the bank balance sheet as part of the refinancing from outside funds. In the case of sight deposits on current accounts, however, the commercial banks usually do not pay any interest on them and generate these deposits for their customers themselves. For most deposits, the banks do not provide the customers with any collateral. In theory, this imbalance is offset by regulating banks.

Interbank lending hardly costs the entire banking sector because all interbank balances add up to zero and the interest costs for banks with a negative balance are the profits of those with a positive balance.

Liquidity and interest rate risks for banks

If a commercial bank generates deposit money that is available daily on its liabilities side in return for longer-term loan agreements on its assets side, it operates so-called maturity transformation . The bank usually benefits from this, as long-term interest rates are usually higher than short-term ones (see interest structure ). However, it carries the associated liquidity and interest rate risks .

It would have to be B. long-term items on the assets side of a bank are quickly sold at unfavorable prices if these conditions are met:

- More customers than expected want to withdraw money or transfer money to other banks.

- There is no trust from other banks to grant interbank loans (bad credit rating ).

- Due to a lack of collateral, central bank money can no longer be procured from the central bank either.

Part of the commercial banks' risk management is therefore to raise savings or time deposits with deadlines that match their loan agreements and assets. In this way you can moderate the maturity transformation. When setting interest rates for these longer-term financial products, the outlook for future monetary policy of the central bank is important. Customers will only commit to a longer term if the interest rate at least reaches the expected rate of interest on overnight money during the term. In addition, concepts such as time preferences , opportunity costs or customers' liquidity preferences have an influence.

Compared to Basel II, the international Basel III framework focuses in particular on banks' liquidity risks. Minimum standards for the newly defined liquidity coverage ratio (LCR) and structural liquidity ratio (NSFR) are required there.

Loan default

If a loan is not serviced by a bank customer and fails, the bank can of course not simply destroy the book money previously generated in return, since it was finally transferred to other customers through payment processes. For the bank, therefore, the loss on the assets side remaining after the collateral has been realized is reflected in reduced equity. This is the credit risk for the bank. The freely circulating deposit money, which after the failure is no longer matched by any credit agreement in a bank balance sheet, is reduced again over time by the banking system through an interest surcharge on the other credit agreements. This increases the banks' equity again. In addition to economic growth, this is one reason why loan rates are consistently higher than deposit rates.

If a bank defaults too many loans, it no longer meets the capital requirements of the financial regulator and can thus be forced to liquidate . Customers can lose their deposits because they represent liabilities of the bank that are included in the insolvency proceedings. In earlier times, it was in these situations then called switch storms (English bank run ), where many depositors wanted to transfer in cash required or secure institutions on switch their money. Today there is a statutory deposit insurance in most countries . This secures deposits in all EU member states of up to € 100,000 per person by obliging credit institutions to participate in joint, pay-as-you-go compensation schemes.

If too many or a few very important, systemically important banks in an economic area are insolvent, the financial system can collapse: credit and investments are then no longer available as expected. The massive bankruptcy may blow the security systems. Insufficient credit supply and defaulted deposits lead to payment difficulties, bankruptcies and unemployment in other areas of the economy. To assess the likelihood of such scenarios, the supervisory authorities carry out so-called stress tests .

Limitation of money creation

The amount of book money drawn is limited on the one hand by customer demand for credit at the given interest rates. On the other hand, loans with interest rates influenced by the central bank are in principle not a scarce commodity for banks, but their lending is also limited by profit and risk considerations ( credit risk , liquidity risk , interest rate risk ) by commercial banks . When banks buy assets, there are also risks of price changes and default, which must be weighed against possible profits. In addition, regulations of the financial market supervision apply , in particular ordinances within the framework of Basel III .

Other influences on the money supply

The European Central Bank's broadest definition of the amount of money , M3, only covers deposits and related financial products with a term of up to 2 years. According to this definition, money is created when bank liabilities that are not part of the money supply (e.g. longer-term time and savings deposits) are converted into short-term bank liabilities that are part of the money supply (e.g. sight deposits). Ultimately, such transactions have their origins in money creation processes from the past, since longer-term bank liabilities usually arose from sight deposits.

If buyers from another currency area transfer money, exchanged for euros, to accounts in countries of the European Monetary Union, sight deposits, i.e. money, are created at the receiving commercial banks. This is the case with a trade surplus .

If banks buy back their own shares from non-banks, the money supply increases as deposits are created in turn. The opposite operations destroy money in a currency area accordingly.

The role of the state

The state, represented in Germany by the Central Bank in the Federal Payment and Accounting Department of the General Customs Directorate under the supervision of the Federal Ministry of Finance , maintains - like the commercial banks - a central bank money account directly with the central bank. Tax payments, i.e. payments from citizens or companies to the state, must therefore be paid by the taxpayer's banks in central bank money.

In explaining the monetary base above, it was mentioned that central bank money is a claim against the central bank. However, it was not said what the content of this demand is. Since the global end of the gold standard in the 1970s, this can no longer be a requirement for a certain amount of gold.

However, as early as 1905, Georg Friedrich Knapp stated in his work The State Theory of Money that money is a creature of the legal system: The state's demand that taxes be paid exclusively in the currency it has set itself implies this currency in one State through. In other words, central bank money is a claim against the central bank to be able to settle money debts of all kinds and in particular tax debt in this state.

The state as a participant in the capital market

Since the founding of the European Monetary Union , the participating states are no longer permitted to receive loans directly from the central bank like commercial banks ( Art. 123 TFEU ). If states want to raise money beyond their tax revenues, they can issue government bonds with different maturities. These are initially bought by commercial banks with central bank money, which they receive in part from the central bank at the key interest rate by presenting the purchased bonds as security. However, the state does not keep the central bank money, but rather it flows back into the banking system with its spending on bank customers. Thus, in times of conventional monetary policy, the banking system partially finances government bonds, as just described, through loans from the central bank, but to a greater extent through customer deposits.

Some of the bonds end up in the hands of private or other investors through resale by the banks. If central banks now buy up government bonds as part of open market operations or to a large extent in programs for “quantitative easing”, the difference to direct government financing is small. The difference is that commercial banks earn and have a say in issuing the bonds. The commercial banks were originally supposed to carry out the credit check of the individual countries in cooperation with the rating agencies. The different creditworthiness would then be reflected in the interest on the bonds of the different countries. However, this system led to the euro crisis in 2010 .

At the end of this, the European Central Bank signaled in a speech by its President Mario Draghi ( whatever it takes ) that it would not accept very high interest rates on bonds from member states and the associated risks of national bankruptcy or an exit from the euro. If necessary, it would itself buy sufficient quantities of government bonds from the member states on the secondary market with self-generated central bank money. As a result, interest rates on all government bonds in the monetary union fell to a very low level.

Modern Monetary Theory

Not all countries in the world forbid direct central bank loans. The Modern Monetary Theory (MMT), which is currently challenging the views of established economists on public finances in America and Australia, considers prohibitions of this kind to be harmful and the individual states in the European Monetary Union to be financially not sovereign.

The MMT states that the central bank and the finance ministry are both institutions of the state and that the direct generation of money by the state can often be a useful option for currency control.

The creditworthiness of a state that is indebted in its own currency is beyond question because of the ability of its central bank to create money. However, with coordinated monetary and financial policy, the effects on the inflation rate must always be assessed. The MMT sees government bonds as a means of monetary policy against inflation and not as a means of financial policy to "finance" the state. According to MMT, government bonds enforce the central bank's key interest rate as they shut down excess reserves in the banking system that enter through government spending. The state's expenditure would simply generate the central bank and the finance ministry, they would not have to be financed. Similarly, it explains the purpose of taxes, along with redistributing and enforcing the currency, as a measure against inflation.

According to MMT, taxes and government bonds on the one hand and government spending on the other largely regulate the value of money. However, the extent to which inflation control is required depends on how inflationary the various government expenditures are. According to MMT, the question is whether the investments create additional real resources in an inflation-neutral way or whether the additional money merely competes for existing resources, which would lead to inflation. Taxes and bonds together do not have to be the same as spending, as politics and parts of economics have been suggesting so far.

The MMT claims to be able to explain the state of the de facto massive state financing by the central banks in Japan, the USA and Europe, which has persisted for years, with at the same time very low inflation and low interest rates.

history

Money creation has always been an essential element of monetary and currency policy . In the history of money, the existing monetary order has always been different. At first they paid with primitive money, later with coins . Additional money was therefore only issued in relation to the additional mining of corresponding precious metals such as gold and silver .

With the advent of the coin shelf , money creation was reserved for the state only. On counterfeit money or individual character was a high penalty. At certain times, many coins were minted using coin scoring . The issue of banknotes did nothing to change these facts. From then on, however, it was partly possible for note banks to also hand out notes or banknotes beyond personal deposits . Some institutes secured themselves through guilds .

In addition, savings banks and cooperative banks were created , which from then on granted loans . The banknote monopoly also gradually fell into the hands of the state, so that the number of currencies decreased. In the history of money , phases of intrinsic money (materially pledged such as gold or gold currency standard ) have been replaced in large numbers with “ fiat money systems” (also due to war financing).

reception

In an interview with the FAZ in 2009, Josef Ackermann and his doctoral supervisor Hans Christoph Binswanger interpret Johann Wolfgang von Goethe's Faust. The tragedy part two . They shed light on the magic that lies in the creation of money and the ambivalence of the money created on Mephistopheles' suggestion in its effect through the bet on time with the risk of triggering inflation and violence, greed and greed, the "journeymen Raufebold, Habebald and Haltefest ”to attract. Goethe also deals with the change from fiefdoms , which must be treated with care, to property that can be “used, but also consumed, plundered, destroyed”, and the omnipotence dreams of man (in the person of Faust) that are triggered by this in the work his economic experience from ten years as finance and economics minister at the Weimar court and his extensive studies of economics processed. Ackermann also warns, however, that a return to the gold standard would mean a very strong reduction in the money supply and would have serious disadvantages. He also points out: "But you also have to be aware that with less money creation and less growth, general prosperity will probably also be lower."

Within economics , monetary theory deals with the theory of money and that part of credit theory deals with its creation. There are different monetary systems . Within systems with a coinage or banknote monopoly the base money will automatically monopoly award within a State by law assigned to an institution, usually the central bank. This contrasts with free banking , which does not require any privileges or restrictions for banks. A further distinction is made between minimum reserve systems and full reserve systems . To maintain monetary stability or targeted weak inflation of z. A monetary policy is necessary to guarantee, for example, 2% . Knut Wicksell's findings (Wicksell process) still have a significant influence on monetary policy decisions today.

See also

- Bank for International Settlements

- Banking management

- Central bank digital money

- Free banking

- Complementary currency

- Cryptocurrency

- Market rate method

- Regional currency

- Circulation secured money

- Sovereign money system

- Full reserve system

literature

- Hans Christoph Binswanger: The growth spiral - money, energy and imagination in the dynamics of the market process. Metropolis Verlag, Marburg 2006. ISBN 3-89518-554-X

- Mathias Binswanger: Money out of nowhere. Wiley, Weinheim 2015. ISBN 978-3-527-50817-4 .

- Jesús Huerta de Soto: Money, Bank Credit and Business Cycles. Hayek Institute, Madrid 2009.

- Joseph Huber: Monetary Modernization. On the future of the monetary order. Metropolis Verlag, Marburg 2010.

- Niklot Klüßendorf: “The copper exchange” by the alchemist Johann Steitz for the Schmalkalden reign. An early modern money creation project. In: Bank historical archive. 1/1989, magazine for banking history, Frankfurt am Main.

- Dieter Lindenlaub: Looking for an instrument to control money creation. Central bank and banks in Germany in the first third of the 20th century. In: Bank historical archive. 2/2000, magazine for banking history, Frankfurt am Main.

- Ann Pettifor : The production of money: A plea against the power of the banks . Hamburger Edition, Hamburg, 2018, ISBN 386854318X

- Michael Rowbotham: Goodbye America. Globalization, Debt and the Dollar Empire. Carpenter Publishing, Charlbury / Oxfordshire, 2000, ISBN 1-897766-56-4 .

- Martin Scheytt: Theoretical fundamentals of lending in banking. Dissertation. Duncker & Humblot, 1962.

Web links

- Information brochure "Implementing Monetary Policy in the Euro Area" , European Central Bank, 2006 (PDF, 1 MB)

- Information brochure "The Monetary Policy of the ECB" , European Central Bank, 2011 (PDF, 2 MB)

- Historically interesting, outdated, misrepresentation of money creation, publication by the Deutsche Bundesbank , 2007, p. 48ff .: Money and Monetary Policy ( Memento from September 29, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF, 3.6 MB)

- Deutsche Bundesbank, educational offers

- was-ist-geld.de , detailed explanation of money creation, University of Hamburg

Individual evidence

- ^ Deutsche Bundesbank, Glossary , Central Bank Money

- ↑ Deutsche Bundesbank, Student Book Money and Monetary Policy , Chapter 6, Open Market Operations

- ↑ Deutsche Bundesbank, Monthly Report April 2017 , The role of banks, non-banks and central banks in the money creation process, page 17

- ↑ Deutsche Bundesbank, Monthly Report April 2017 , The role of banks, non-banks and central banks in the money creation process, page 26

- ↑ Deutsche Bundesbank, Monthly Report April 2017 , The role of banks, non-banks and central banks in the money creation process, page 16

- ^ The monetary policy of the ECB 2011 , page 64

- ^ The monetary policy of the ECB 2011 , page 9

- ^ Deutsche Bundesbank, Student Book Money and Monetary Policy , Chapter 3, Money Creation

- ↑ Bank of England: Money creation in the modern economy | Bank of England. March 14, 2014, accessed June 10, 2018 .

- ↑ Deutsche Bundesbank, Monthly Report April 2017 , The Role of Banks, Non-Banks and Central Banks in the Money Creation Process, page 19f

- ^ Deutsche Bundesbank, Glossary , Minimum Reserve

- ↑ European Central Bank, Eurosystem , What is the minimum reserve requirement?

- ↑ Xavier Freixas / Jean-Charles Rochet, Microeconomics of Banking, 1997, MIT Press ISBN 978-0-262-06193-3 , The Competitive Equilibrium of the Banking Sector p. 55f, The Transmission Channels of Monetary Policy, Endogenous Money, p 167

- ^ European Central Bank, Occasional Paper Series No. 155 / September 2014, The Retail Bank Interest Rate Pass-through, the case of the Euro area during the financial and sovereign debt crisis

- ↑ Deutsche Bundesbank, monthly report article April 2019, interest rate transmission in the low interest rate environment

- ↑ Deutsche Bundesbank, Student Book Money and Monetary Policy , Chapter 3, The formation of savings and time deposits

- ↑ Deutsche Bundesbank, Monthly Report April 2017 , The role of banks, non-banks and central banks in the money creation process, page 20

- ↑ https://www.zrb.bund.de/DE/ZFB/Zentralkasse/Zentralkasse_node.html

- ↑ Dirk H. Ehnts: Money and Credit: A Euro-Pean Perspective. Metropolis-Verlag , 2020, 3rd revised and updated edition, ISBN 978-3-73161412-8

- ↑ Paul Terres: The logic of a competitive monetary order. Tübingen 1999. ( online ) p. 42.

- ^ Josef Ackermann and Hans Christoph Binswanger: The money is missing. Well, then do it! In: FAZ Online from June 30, 2009.

- ↑ See e.g. B. the "target of an inflation rate of almost two percent" at the ECB , status 2015, n-tv

- ^ History of Economic Thought: Paradigm Shift in Economics. ISBN 978-3-486-58522-3 , p. 141.