European Economic and Monetary Union

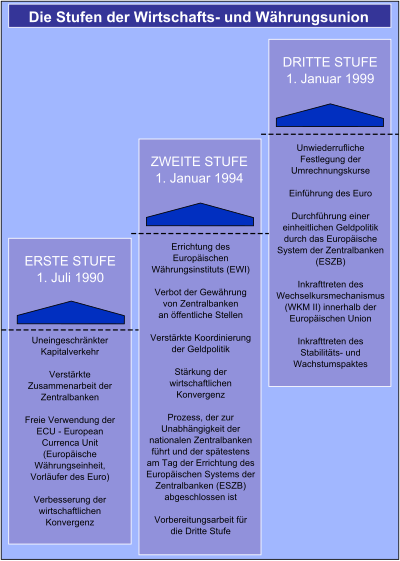

The European Economic and Monetary Union , EMU , (shortened also Economic and Monetary Union , EMU ; unofficially also European Monetary Union , EMU ; English Economic and Monetary Union , EMU) is an agreement between the member states of the European Union . July 1990 through the implementation of certain economic and monetary policy regulations in a three-stage process. The main aim of the EMU regulations is to complement the European internal marketthrough a common currency with a high level of price stability .

So far, the 27 EU states have implemented the EMU agreement to varying degrees. It is uncertain - and in view of the euro crisis since the outbreak of the Greek sovereign debt crisis in autumn 2009 also improbable - that all EU states will be fully integrated into the EMU regulations at the end of the implementation process. The currency euro introduced since January 1, 1999 19 of the 27 EU countries ( " Euro Zone "): Belgium, Germany, Estonia, Finland, France, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, the Netherlands, Austria, Portugal, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain and the Republic of Cyprus. These 19 countries coordinate their economic and financial policy within the framework of the Euro Group . Of the other eight EU countries, six are obliged to introduce the euro as soon as they meet the agreed convergence criteria .

The two EU states Denmark and Sweden have de jure and de facto an opt-out option from the obligation to introduce the euro. The eight EU states that are not yet part of the euro zone have also implemented the EMU regulations in various aspects and are coordinating certain areas of their economic and monetary policy with the group of 19 euro zone countries.

Member States of the EMU

All 27 EU countries are formally members of the EMU. In a narrower sense, the term is sometimes restricted to the nineteen Member States that are taking part in the third stage, that is to say that have introduced the euro as their currency . These are Belgium , Germany , Estonia , Finland , France , Greece , Ireland , Italy , Luxembourg , Latvia , Lithuania , Malta , the Netherlands , Austria , Portugal , Slovakia , Slovenia , Spain and the Republic of Cyprus .

Eight other EU countries have not yet introduced the euro: Bulgaria , Denmark , Croatia , Poland , Romania , Sweden , the Czech Republic and Hungary . Different types of exception regulations apply to these states: While Denmark was not obliged to participate in the EMU from the start due to a so-called opt-out clause , all other states must adopt the euro as their currency according to the EU and AEU treaties as soon as they meet the EU convergence criteria. One of these criteria is the so-called Exchange Rate Mechanism II (ERM II), in which the country's currency is linked to the euro rate within a certain fluctuation range for two years. Denmark, Croatia and Bulgaria are currently participating in ERM II.

It remains to be seen whether the other countries will aim to introduce the euro as soon as this is economically possible for them. Sweden met the criteria for the introduction of the euro before the outbreak of the global economic crisis in 2009/2010 ; however, it deliberately missed it by not taking part in ERM II, as the population voted against the euro in a referendum (on September 14, 2003). This practice actually contradicts the meaning of the treaty. It is tolerated by the European Commission because Sweden joined the EU at a time when the introduction of EMU had already been decided, but the third stage had not yet been reached. In a sense, Sweden has an “informal opt-out”.

A withdrawal of individual countries from the monetary union, as it has been publicly discussed since 2010 as a result of the Greek financial crisis , is not expressly provided for in the AEU Treaty . In the opinion of many, it is only possible if a country leaves the EU as a whole (in this case Article 50 of the EU Treaty applies ) or by negotiating a supplementary agreement, for example in the form of an additional protocol to the FEU Treaty. This would have to be ratified by all member states . On the other hand, some of the literature would like to assume a right to unilaterally exit the monetary union even if the relevant member state no longer meets the membership requirements.

EU convergence criteria

In order to be able to participate in the EMU, the member states must comply with certain rules that are intended to guarantee a certain degree of standardization and stability of their economic and fiscal situation. These EU convergence criteria ( also referred to as Maastricht criteria after the Maastricht Treaty ) can be found in Art. 140 TFEU .

In detail, these are the following criteria:

- Price stability : The inflation rate must not be more than 1.5 percentage points above that of the three Member States with the most stable prices.

- Stability of the public finances: the state debt level must not exceed 60%, the annual net new debt not more than 3% of the gross domestic product .

- Exchange rate stability: the state must have participated in Exchange Rate Mechanism II for at least two years without devaluing . The country's currency may only deviate from the euro rate within a certain exchange rate range (usually 15%); the country's central bank must intervene in the event of major deviations.

- Long-term interest rates: The interest rate on long-term government bonds must not be more than 2 percentage points above the average of the three most stable Member States.

The European Commission and the European Central Bank check at least every two years whether the member states that have not yet adopted the euro meet the convergence criteria. As soon as a state fulfills them, it can apply to join the final stage of EMU. The Commission then makes a recommendation, taking into account other criteria such as market integration, the current account balance and the country's unit labor costs ; there are no fixed limit values to be observed here. There is a debate in the European Council and a hearing in the European Parliament on this Commission recommendation . Decisive for the admission of the applicant country is the Council for Economic and Financial Affairs , which decides by a qualified majority , whereby only those member states that have already introduced the euro have a voting right ( Art. 140 (2) TFEU). So far, these decisions have always been made in accordance with the Commission's recommendation.

Demarcation from the euro zone

The term Eurozone (also Eurozone , Euroland ) is mostly used in the narrower sense to denote the nineteen countries that have introduced the Euro as their currency. In this meaning it is synonymous with the term European Economic and Monetary Union in the narrower sense.

Sometimes, however , the euro zone is also used in a broader sense for all countries that use the euro, even if they are not EU members. These include Andorra , Monaco , San Marino and the Vatican City , which due to bilateral agreements with the EU have the right to use the euro as the only currency and to have their own euro coins minted to a limited extent, as well as almost twenty other countries or parts by states that have unilaterally introduced the euro as their currency or have linked the rate of their currency to the key currency, the euro.

Contractual bases and goals

The term European Economic and Monetary Union goes back to the political debate of the late 1980s and is still used today. In European primary law itself it is hardly used: In Art. 3 , para. 4 EU Treaty is called the establishment of a "Economic and monetary union whose currency is the euro" as the goal of the EU. In the FEU Treaty, on the other hand, mostly only the “economic and monetary policy” of the EU is mentioned ( Art. 119 ff. FEU Treaty). The states that participate in the third stage of EMU are referred to as "Member States whose currency is the euro" ( Art. 136 ff. TFEU Treaty), the others as "Member States for which an exception applies" ( Art. 139 ff. FEU Treaty).

The fundamentals of the economic and monetary policy of the EU are regulated in Art. 119 to Art. 144 TFEU , whereby under economic policy essentially the process policy is meant. There are also numerous other policy areas of the European Union that also have strong economic ties (such as EU employment policy , EU social policy or the European internal market ). However, they are usually not included under the term EMU, as their contractual bases are older. In contrast to the EMU, the EU not only has a coordinating function there, but can also legislate itself . The influence of the European Commission and the European Parliament is therefore greater in these areas than in the context of EMU.

The prevailing principle of EMU in the economic sector is the open method of coordination : the nation states can largely determine their economic policy themselves within certain frameworks, but they are required to coordinate this with one another in the Council of the EU . The supranational institutions such as the European Commission and the European Parliament have formally only limited competences. However, the Commission has a certain informal influence as it assists the coordination by producing reports which the Member States can use as a basis for decision-making.

In contrast, the distribution of competencies is different in the currency area: Here, the euro states in particular have transferred numerous sovereign rights to the European Central Bank , which can make decisions as an autonomous and independent body . In the countries that have not introduced the euro, the competence lies with the national central banks , which must be independent of all other government agencies in their decisions. All national central banks of the EU coordinate their activities in the European System of Central Banks .

According to Article 3 of the EU Treaty and Article 119 of the TFEU, the objectives of European economic and monetary policy are the close coordination of the economic policy of its member states and the European internal market . Economic policy is based on the principle of the “open market economy with free competition ” (which, however, does not see any contradiction to the social market economy , which according to Article 3 of the EU Treaty is also one of the goals of the EU). In EU monetary policy, the primary objective is price stability . If this is possible while maintaining price stability, currency policy should support general economic policy as far as possible ( Art. 119 TFEU).

"Stable prices, healthy public finances and monetary framework conditions as well as a sustainable balance of payments" are named as "guiding principles". These four principles largely correspond to the EU convergence criteria . In this context, the published European Commission in January 2019 and the Sustainability Report Fiscal Sustainability Report 2018 to the fiscal situation of the Member States of the European Union .

Economic regulations

Multilateral surveillance

Economic policy is essentially coordinated through what is known as “multilateral surveillance” ( Art. 121 TFEU). In doing so, the Council of the European Union (Council of Ministers) draws up recommendations on the proposal of the European Commission and after consulting the European Council , in which it defines the main features of the economic policy of the EU as a whole and of the member states. They are based on long-term economic strategies , so far the Lisbon Strategy for the period 2000–2010 and Europe 2020 for the period 2010–2020.

The Commission prepares regular reports on the implementation of these recommendations on the basis of information sent to it by the individual Member States. However, there are only very weak sanction mechanisms if Member States do not comply with the recommendations: in this case the Commission can only issue a “warning”; the council can only formulate recommendations and publish them if necessary. The multilateral surveillance therefore works more through political pressure, not through actual coercive mechanisms of the EU institutions.

In addition to the broad economic policy guidelines that apply to the EU as a whole, the Council also uses the same procedure to develop broad economic policy guidelines specifically for those states that have introduced the euro as their currency ( Art. 136 TFEU). Only representatives of the Eurogroup ( see below ) take part in these Council meetings .

The European Parliament is only marginally involved in multilateral surveillance. It is informed by the Council of Ministers and the Commission about the economic policy recommendations and the results of the monitoring, but does not itself participate in them.

Stability and Growth Pact

A somewhat stricter procedure than for general economic policy applies to the monitoring of national public debt . The convergence criterion , according to which the debt level must not exceed 60% and the annual net new debt must not exceed 3% of the gross domestic product , was permanently established within the framework of the so-called Stability and Growth Pact ( Art. 126 TFEU ). The European Commission checked annually to all EU Member States, including those which have not adopted the euro as their currency. If a Member State does not comply with the criteria, or if the Commission believes that there is a risk, it will draw up a report. On the basis of this report, the Council of the EU decides with a qualified majority how to proceed. When it comes to a country that has introduced the euro as its currency, only the member states of the euro group are entitled to vote; for the other countries, the entire council is entitled to vote. This can take a number of measures, escalating from economic policy recommendations to various means of coercion, in particular fines. According to Art. 139 TFEU, however, these means of coercion can only be applied to Member States that have adopted the euro as their currency. The other states are also obliged to comply with the Stability Pact, but the Council can only make recommendations to them.

Although the Commission has already started several proceedings for breaches of the Stability Pact, the Council has not yet actually imposed any sanctions. The reason for this is, on the one hand, that fines would only worsen the budgetary position of an already over-indebted state. On the other hand, the fact that the final decision on sanctions is taken by the national finance ministers in the Council, who may themselves run into an excessive budget deficit at another point in time, is seen as a reason for the less strict interpretation of the stability pact. The historical root of the problem lies in the EU summit in Dublin in December 1996, when Chancellor Helmut Kohl - after massive French pressure - waived the originally intended standardization of automatic penalties. Better enforcement of the Stability and Growth Pact is therefore one of the most important topics of discussion when it comes to the further development of the EMU ( see below ).

Intergovernmental solidarity and no bailout clause

Mutual economic aid between the member states or from the EU to the member states is only provided for within a narrow framework within the framework of the EMU. (Other areas, such as EU regional policy , on the other hand, expressly provide for financial transfers between different parts of the EU.) According to Art. 122 TFEU, the Council of Ministers can, however, take measures in emergency situations, particularly in the event of supply bottlenecks. In the event of natural disasters and other “exceptional events beyond its control”, a Member State can also receive financial aid from the EU budget if the Council decides .

Art. 143 TFEU also provides for a special procedure of "mutual assistance" for member states that have not yet introduced the euro and arecaughtin a balance of payments crisis. On a proposal from the Commission, the Council of Ministers can adopt various measures,rangingfrom coordinated action by international organizations such as the International Monetary Fund to voluntary loans from other member states.

The intra-European solidarity is limited by the so-called no-bailout or non-assistance clause , which excludes liability of the EU and the individual member states for the debts of other member states ( Art. 125 TFEU). This regulation complements the Stability Pact and is intended to ensure that no member state can use its budgetary autonomy to incur debt at the expense of other member states. This is intended to preserve the responsibility of each state for its national deficit and to prevent moral hazard .

The exact interpretation of the clause is controversial after the decision to grant loans to an EMU member state as a result of the Greek financial crisis in 2010 and the euro states assuming guarantees for one another within the framework of the European Stability Mechanism ( see below ). Further loans to Ireland (2010) and Portugal (2011) made it increasingly questionable whether the no- bailout clause prohibits any form of bailout , i.e. also the voluntary assumption of debts from other member states, or merely excludes automatic and compulsory liability.

Ban on central bank lending

A key requirement for the introduction of EMU was the independence of all national central banks . This was to prevent the governments of the member states from financing their economic policy by increasing the amount of money and thus by generating inflation , as had happened in various European countries before the establishment of the EMU. Art. 123 and Art. 124 TFEU therefore prohibit any type of credit facility from the European Central Bank or the national central banks to the member states and any preferential access by public-law institutions to the banks. The direct acquisition of government bonds by the central banks is also prohibited (i.e. the purchase of government bonds as opposed to indirect / indirect acquisition via deposited collateral in the event of default).

During the euro crisis , however, the European Central Bank began to interpret this regulation in 2010 in such a way that an indirect acquisition of government bonds, i.e. the purchase through private middlemen, is not excluded (indirect, i.e. in the sense of the indirect route and not in the sense of acquisition by leasing instead of direct purchase). Critics saw this as a breach of the purpose of the legal provision, since the economic consequences of an indirect or direct acquisition of government bonds by the central bank are hardly different, and accused the ECB of having given in to the political pressure of the European Council . The ECB itself emphasized, however, that it had made its decision on its own and that its independence was not jeopardized in this respect. Individual members of the Governing Council, in particular the President of the German Bundesbank, Axel A. Weber , criticized the ECB's attitude. Weber later resigned - presumably in protest; likewise the German ECB chief economist Jürgen Stark .

Special institutions

There are some special institutions to facilitate economic and financial policy coordination between the EU member states in general and the euro states in particular.

Eurogroup

In numerous decisions of the Council for Economic and Financial Affairs that only affect the euro area , only those countries that have introduced the euro are entitled to vote. That is why their economics and finance ministers meet for informal meetings on the eve of the council meetings. This so-called Eurogroup is regulated in Art. 137 TFEU and in Protocol No. 14, which is annexed to the TFEU. The Commissioner for Economic and Monetary Affairs and a representative of the European Central Bank also take part. With its informal character, the Eurogroup is the most important coordination forum in the EMU.

The Eurogroup was set up unofficially in 2004 and was anchored in the Treaty of Lisbon in 2009. It appoints a president for a period of two and a half years; from 2004 to 2013 this was the then Luxembourg Prime Minister Jean-Claude Juncker , who was also his country's finance minister until 2009. From 2013 to 2018 the Dutch Finance Minister Jeroen Dijsselbloem and from January 2018 to June 2020 the Portuguese Finance Minister Mário Centeno chaired the Eurogroup. Irish Finance Minister Paschal Donohoe has held the chair since July 2020 .

On October 12, 2008, on the occasion of the financial crisis from 2007 onwards , a summit meeting of the euro states at the level of the heads of state and government ( European Council ) took place for the first time.

Economic and Financial Committee

The Economic and Financial Committee is an advisory body made up of two representatives from each EU member state, the European Commission and the European Central Bank ( Art. 134 TFEU ). It monitors the economic and financial situation in the EU and its Member States and reports on them to the Commission. He also collaborates with the Permanent Representatives Committee in the preparation of certain activities of the Council on Economic and Financial Affairs . This concerns in particular multilateral surveillance and the excessive deficit procedure.

The Economic and Financial Committee is the successor to the Monetary Committee, an advisory body of senior national tax officials that has existed since the early stages of European integration.

Monetary policy regulations

European System of Central Banks and European Central Bank

The most important institution of the EMU in the area of monetary policy is the European System of Central Banks (ESCB), which is composed of the national central banks of the member states and the European Central Bank (ECB). Their functioning is regulated in Art. 127 to Art. 133 TFEU and in the statute, which is annexed to the EU treaties as Protocol No. 4. The governing bodies of both the ECB and the ESCB are the ECB Executive Board, which is composed of the President and Vice-President of the ECB and four other persons, and the Governing Council, in which, in addition to the Executive Board members, the national central bank governors of those countries are represented introduced the euro. While the Governing Council is responsible for setting monetary policy and issuing the necessary guidelines, the ECB Executive Board is responsible for the operational activities in order to implement the monetary policy decided by the Governing Council. The Executive Board of the ECB is authorized to issue instructions to the national central banks of the countries that have introduced the euro . According to Art. 139 Para. 3 TFEU there are a number of other regulations of the ESCB that only apply to the central banks of those states that have introduced the euro. The term Eurosystem has therefore also been established for these, although this is not used in the text of the treaty.

According to Art. 130 TFEU, both the ECB and the national central banks must be completely independent of all government and other bodies. According to Article 14 of the ESCB Statute, certain additional regulations also apply to the national central banks, which are also intended to prevent informal influence by the government of the respective country. This includes in particular that the president of a central bank must be appointed for at least five years and can only be dismissed in the event of serious misconduct. In case of doubt, the European Court of Justice decides whether such a serious misconduct has occurred . These regulations also apply to countries that have not yet introduced the euro.

The European Central Bank has the status of an organ of the European Union. It must be heard in all legislative procedures that fall within its area of responsibility ( Art. 127 (4) TFEU). It is the only institution that has the right to authorize the issuance of euro banknotes and coins ( Art. 128 TFEU). However, the coins are issued by the national central banks.

Price stability as a top priority

The primary objective of the ESCB is to ensure price stability , i.e. the lowest possible inflation . It differs from other central banking systems such as the American Federal Reserve System , which has other goals such as low unemployment and low long-term interest rates. The ESCB, on the other hand, can only support the general economic policy of the EU insofar as this is "possible without impairing the goal of price stability" ( Art. 127 TFEU).

According to Art. 139 TFEU , the central banks of the states that have not introduced the euro are not bound by the objectives of the ESCB. So you can pursue your own monetary policy goals. According to Art. 142 TFEU they are obliged to treat exchange rate policy as a "matter of common interest"; however, there are no formal mechanisms by which this would be controlled.

Common appearance in international organizations

According to Art. 138 TFEU, the states that have introduced the euro define common positions in the Council for Economic and Financial Affairs , which they represent in international organizations and at international conferences that deal with the international monetary system or other financial issues. You can also decide to be represented uniformly. The European Central Bank must be consulted before the Council's decisions. Countries that have not introduced the euro do not take part in the decisions.

Beyond the agreements within the framework of the EMU, according to Art. 219 TFEU , the member states have the right to negotiate independently in international bodies and to reach agreements. In April 2008, Jean-Claude Juncker, President of the Eurogroup , proposed setting up a unified representation of the euro states at the International Monetary Fund , where each member is represented individually. Joaquín Almunia , then Commissioner for Economic and Monetary Affairs , however, stated that a common economic policy agenda was necessary before a joint representation.

Participation in international exchange rate systems

According to Article 219 of the TFEU, the European Union can conclude agreements with other states on the establishment of exchange rate systems . The decision is made unanimously by the Council of the EU after hearing the European Central Bank and the European Parliament, whereby only those states that have introduced the euro as their currency are entitled to vote. One such exchange system is, for example, Exchange Rate Mechanism II .

In working with countries with which there is no exchange rate system, the Council can provide general guidelines for exchange rate policy. In doing so, the primary objective of the ESCB, price stability, must not be jeopardized.

story

Forerunner of the EMU

Monetarists and economists

The first proposals for a European monetary union were made very early in the history of European integration . Both the Belgian politician Paul van Zeeland and the French Foreign Minister Georges Bidault proposed corresponding initiatives as early as the 1940s, which initially had no impact. The European payments union, which existed from 1950 to 1958, can be seen as a forerunner of a European monetary union based on Keynes' Bancor plan. The first concrete plans emerged soon after the signing of the Treaty of Rome and the establishment of the European Economic Community (EEC), with which the gradual establishment of a European common market was decided in 1957 . In 1962 the EEC Commission under Walter Hallstein presented the first proposals for the establishment of a monetary union. In 1964 the "Committee of the Presidents of the Central Banks of the Member States of the European Economic Community" (Board of Governors) was founded, in which the monetary and currency policy of the EEC member states was to be coordinated. However, at that time there was little political interest in a monetary union, since the Bretton Woods system was in effect internationally anyway , which fixed exchange rates between all major currencies. The member states were also not prepared to completely give up sovereignty over monetary policy. The Commission's plans were therefore not pursued any further.

In addition, the different ideas between the member states, which were divided into "monetarists" and "economists", soon became apparent: while the first group, particularly France, sought a rapid monetary union that was to serve as a "motor" for political rapprochement between the states , the economists, especially Germany, initially demanded an approximation of economic policy in the various countries and saw the monetary union merely as the “crowning achievement” of the harmonization process.

Werner plan and currency snake

In the mid-1960s, the Bretton Woods system came under increasing pressure. In February 1969, therefore, Raymond Barre , the Commissioner for Economic and Financial Affairs , again proposed the gradual establishment of a monetary union. At the 1969 summit in The Hague , the heads of state and government of the EEC member states finally commissioned a commission headed by Luxembourg Prime Minister Pierre Werner to draw up a plan for economic and monetary union. This Werner Plan tried in particular to overcome the contradictions between monetarists and economists using a three-step model. In the last stage, monetary policy should be subject to a common central bank system, and economic policy to a body subordinate to the European Parliament . However, the exact schedule of the sequence of stages remained open.

In March 1971, a few months before the collapse of the Bretton Woods system, the EEC Council of Ministers made the fundamental decision to implement the Werner Plan by 1980. Therefore, on March 21, 1972, the European Exchange Rate Association was founded, in which currency fluctuations between the EEC currencies were only permitted within a range of ± 2.25%. In relation to third currencies, especially the US dollar , the related currencies could move freely, but they each followed each other. That is why one spoke of a currency snake .

The global economic framework of the 1970s turned out to be too difficult to fully implement the Werner Plan. As early as April 1973, the member states decided not to initiate the planned second stage of the Werner Plan. From the end of 1973 the economic situation worsened due to the first oil crisis . By the end of 1978 there were several withdrawals from the exchange rate system, so that it had hardly any effect.

European monetary system

In the summer of 1977, the newly appointed President of the European Commission , Roy Jenkins , therefore proposed a new start in monetary policy coordination. This was taken up by Helmut Schmidt and Valéry Giscard d'Estaing , on whose initiative the European Council decided in December 1978 to develop a new European Monetary System (EMS): At the center of its exchange rate mechanism (ERM) was the newly created European artificial currency ECU , which was composed of a " basket " in which the currencies of the participating countries were represented as a percentage of their economic strength. For the individual national currencies were central rates determined at the ECU to which they were allowed to vary only up to a maximum of ± 2.25%.

According to the plans at the time, the EMS should change into a definitive currency system with the ECU as the common currency. However, the second oil crisis that broke out in 1979 and disagreements over the course of the final phase hampered the introduction of such a system. Also, not all EC states took part in the EMS: Great Britain in particular only joined the EMS in 1989 and left it again in 1992, and Italy also left the EMS temporarily from 1992 to 1996. Greece, Spain and Portugal, which joined the EC in the 1980s, also did not participate in the EMS for different reasons.

In spite of these difficulties, the EMS contributed to the willingness of the member states to achieve economic policy coordination and convergence; From the mid-1980s onwards, inflation was curbed in almost all member states by means of a stability-oriented monetary policy. The Single European Act (EEA) of 1986, in which the completion of the European internal market was decided, once again underlined the importance of increased economic and monetary policy cooperation.

See also the private initiative: Committee for a European Monetary Union

The Delors Report

The continuation of monetary integration was controversial at the end of the 1980s. While the President of the European Commission , Jacques Delors , wanted to resume the goal of economic and monetary union, the presidents of the national central banks , especially Karl Otto Pöhl , the president of the Deutsche Bundesbank , were skeptical. They feared not only economic uncertainties, but also the loss of their own creative freedom. In 1988, however, Delors moved the European Council to set up a working group in which the national central bank governors themselves, chaired by Delors, were supposed to work out plans for a monetary union.

In this working group, Delors was able to overcome the concerns of the central bank governors. In April 1989 the so-called Delors Report was published, which envisaged the implementation of economic and monetary union in three stages. This was supported in particular by France (or by François Mitterrand , who had been French President since mid-1981 ), who saw it as an opportunity to regain lost political influence. The EMU was intended to transfer this dependency from a single member state to a community institution, which at least put all countries in a similar political situation. Above all, Germany, which feared a loss of price stability through a common currency , and Great Britain, which rejected the loss of monetary sovereignty on principle, were skeptical . For both of them, their own currency was also an important symbol of national identity . Despite this skepticism, the Delors Plan was approved by the European Council in June 1989.

The first, as yet insignificant stage of EMU was finally initiated on July 1, 1990. For the implementation of the other stages, however, there was initially no European legal basis, for which a reform of the EC Treaty was necessary. The readiness for this treaty reform came with the German reunification in 1990. Since France and Great Britain also had to give their consent to reunification within the framework of the two-plus-four treaty , the French President François Mitterrand saw an opportunity to defend the German government under Helmut Kohl to move in support of the EMU. At the same time, French and German politicians in particular increasingly saw the need to secure Germany's ties to the West after reunification by deepening European integration in general . The Federal Government ( Cabinet Kohl III ) went one on the French initiative IGC one for EMU. During the negotiations, it set various conditions for the structuring of institutions in order to make the EMU similarly stability-oriented as the German Bundesbank had been. Theo Waigel's German delegation thus largely prevailed: In particular - contrary to the French plans - price stability was declared the highest priority of the European Central Bank and its complete political independence was enshrined in the treaties.

The contractual basis for the completion of EMU was created in February 1992 with the Maastricht Treaty , which came into force in 1993. It contained both the further schedule and the legal provisions for the implementation of the Delors report, such as the EU convergence criteria and the regulations on the European Central Bank . The transition to the second stage of economic and monetary union was set for 1994, the transition to the third stage for a point in time between 1996 and January 1, 1999. The British government under John Major , which had tried to prevent monetary union, failed and was only able to achieve an “opt-out” rule for itself. In October 1992 Great Britain also left the European monetary system on so-called “Black Wednesday” due to the EMS crisis , so that the European Union was now divided in terms of monetary policy.

A special case is Denmark, whose government initially approved the provisions of the Maastricht Treaty. However, after the ratification of the treaty failed in a referendum, not least because the Danish people had reservations about economic and monetary union, the European Council at the Edinburgh summit in December 1992 agreed certain exceptional protocols through which Denmark also had the option of leaving the Monetary Union received.

The first stage of EMU

The first stage in the implementation of EMU was initiated on July 1, 1990, following a decision by the European Council . The main objective of this stage was to align the various national economic and monetary policies more closely with monetary stability and budgetary discipline. In order to achieve a gradual convergence of policies, multilateral surveillance was introduced as a new coordination tool . Twice a year , the Council for Economic and Financial Affairs discussed reports prepared by the European Commission on the economic development and economic policy of the member states. However, the individual member states ultimately remained free and autonomous in their decisions; there were as yet no obligations or coercive measures.

Another component of the first stage was the reorganization of monetary policy cooperation. To this end, the Board of Governors, in which the governors of the national central banks were assembled, was given new responsibilities. He was now able to issue public statements on the monetary policy situation in the Community and began preparing for the establishment of the European Monetary Institute .

In addition, the unrestricted free movement of capital was in effect from the first stage , one of the four fundamental freedoms in the European internal market , the implementation of which had already been decided in the Single European Act . The full free movement of capital had been a condition of Great Britain, among other things, to agree to the initiation of the first stage.

The second stage of EMU

The second stage of EMU began on January 1, 1994 , according to the timetable agreed in the Maastricht Treaty . From this point on, the no-bailout clause and the ban on the national central banks from granting loans to public authorities applied. In addition, the most important innovation was the establishment of the European Monetary Institute (EMI), which replaced the Board of Governors of the central banks. The main tasks of the EMI were on the one hand to strengthen cooperation between the central banks and the coordination of national monetary policies, and on the other hand to create the legal, organizational and institutional prerequisites for the transition to the third stage. To this end, the EMI prepared a report on future monetary and exchange rate relations between the future euro area and the rest of the EU. On the basis of this report, the new Exchange Rate Mechanism II (ERM II) was adopted in June 1997 , which was to replace the European Monetary System from the transition to the third stage of EMU .

In addition, the EMI was entrusted with the design of the banknotes for the new common currency. According to a decision by the European Council at the end of 1995, this should no longer be called the ECU but rather the euro . The German federal government in particular saw this name as "more trustworthy". The first drafts were presented to the Commission in December 1996 and later to the public.

The third stage of EMU

The third and final stage of EMU began on January 1, 1999 with the appointment of the euro as the common currency. From that point on, the central banks of all member states had to be politically independent. In addition, on the basis of a Commission report, the European Council determined which member states met the EU convergence criteria and were therefore allowed to introduce the euro as their currency. These were all Member States except Great Britain, Denmark and Sweden, which did not want the introduction of the euro, and Greece, which did not yet meet the criteria. The European Central Bank (ECB) was founded on June 1, 1998 to replace the European Monetary Institute.

With the start of the third stage, the exchange rates of the currencies of the eleven member states selected by the European Council were irrevocably fixed. In order to economically shield the definition, the national central banks granted the European Central Bank an unlimited credit ( TARGET2 ). From now on it was no longer the national central banks that were responsible for the implementation of monetary policy in these countries, but the European System of Central Banks and in particular the ECB. At the same time, the Exchange Rate Mechanism II came into force.

Euro coins and notes were issued three years after the third stage of EMU began in January and February 2002.

Hopes and fears in founding the EMU

The EMU was already controversial when it was founded; it was the object of great political hopes and fears.

An important hope for the establishment of the EMU was an expected surge in growth , since the single currency in the European single market should lead to an increase in demand and a reduction in costs. The latter should result from the elimination of exchange rate uncertainties , the reduction of transaction costs and the higher market transparency . The poorer member states in particular hoped that the common currency would provide a greater incentive for direct investment from richer countries. In fact, as with the establishment of the European single market , the growth spurt from the EMU was hardly detectable; it was superimposed on other economic events. The transition to the third stage of EMU coincided with the dot-com bubble , which burst a little later and led to a global economic crisis. Overall, growth in the euro zone between 1999 and 2007 was rather mediocre at around 2.2 percent annually (in the USA, GDP grew by 2.8 percent annually during the same period, in the EU as a whole at 2.5 percent).

Another hope in establishing the EMU was the higher price level stability , which the governments of former hyperinflationary countries such as Italy in particular expected by relinquishing the power to make monetary policy decisions to the ECB. The ECB should be able to adopt stability-oriented decisions that would otherwise have been difficult for governments to implement in national public opinion. At the same time, the integration into the EMU on the international financial markets should bring a gain in credibility and reputation for the states concerned. Conversely, in traditionally price-stable countries such as Germany, there were fears that EMU would increase the overall level of inflation. Overall, the inflation rate in Germany has hardly changed since the EMU was founded. However, in the first few years after the introduction of the euro coins, perceived inflation was particularly high; many citizens perceived the euro as “ expensive ”.

Finally, the EMU was also seen as a sign of the formation of a “political union” in Europe. It should raise awareness of European integration and thus support the general peacekeeping goal of the European Union. In Article I-8 of the EU Constitutional Treaty of 2004, the euro was named as one of the symbols of the European Union , alongside the European flag , European anthem , Europe day and European motto . After the failure of the Constitutional Treaty, however , the corresponding article in the Lisbon Treaty was deleted again.

Enlargements of the Eurozone

The Council of the European Union, made up of heads of state and government, decided on May 3, 1998 that the third stage of Economic and Monetary Union would come into force on January 1, 1999 and determined the first eleven participating states in accordance with the EU convergence criteria .

On June 19, 2000, the European Council came to the “view that Greece had achieved a high degree of sustainable convergence and therefore met the necessary requirements for the introduction of the euro”. Following the approval of the Ecofin Council , Greece introduced the euro on January 1, 2001.

On March 8, 2006, Slovenia was the first of the newly acceding states to submit an official application to introduce the euro on January 1, 2007. On May 16, 2006, the European Commission recommended that Slovenia be admitted to the euro area. On July 11, 2006, the Ecofin Council finally approved the introduction of the euro on January 1, 2007, setting the exchange rate at 239.640 tolar for one euro.

On July 10, 2007, the EU finance ministers approved the accession of the Republic of Cyprus and Malta to the euro area. As a result, the number of euro-participating countries rose to 15 on January 1, 2008, and to 16 countries when Slovakia joined the euro area on January 1, 2009.

On June 17, 2010, it was finally decided to join Estonia on January 1, 2011. The final exchange rate was set on July 13, 2010. 1 euro corresponds to 15.6466 Estonian crowns.

Latvia became the 18th country to adopt the euro on January 1, 2014. Lithuania was the last country to introduce the euro on January 1, 2015.

Debate and further development of the EMU

Even after the establishment of the monetary union, the debate continued about whether it had more advantages or disadvantages and in which direction it should be further developed. In view of the positive economic development and rising euro exchange rates, an optimistic assessment prevailed at first. Even during the financial crisis from 2007 onwards , EMU was mostly seen as an advantage for the participating countries; It was a major reason for Iceland's application to join the EU in 2009, and in countries like Denmark, too, interest in EMU membership rose again. With the Greek financial crisis in 2009/10, which quickly expanded into the euro crisis , the discussion about the functioning of the EMU and its general advantages and disadvantages intensified again.

The theory of optimal currency areas

A fundamental argument in the discussion about EMU is the theory of optimal currency areas , which was founded in 1961 by Robert Mundell and further developed by other authors. It tries to weigh up the advantages and disadvantages of monetary unions and to draw up a cost-benefit analysis that can be used to examine whether a monetary union makes sense in a particular case.

One advantage of currency integration is the reduction in transaction costs , which results from the single currency for both companies and households. Both economic entities benefit on the one hand from the no fees for currency exchange and on the other hand from the limitation of exchange rate uncertainty . Another advantage can be seen in the increase in market transparency . This leads to a reduction in the information costs for the individuals who can now directly compare the prices within the currency area with one another.

A disadvantage of a monetary union, on the other hand, is the loss of flexible exchange rates as an adjustment mechanism when the economies of two regions or countries diverge. If, for example, productivity increases faster in one region than in another, with flexible exchange rates this leads to an appreciation of the currency in the more productive region, thereby restoring economic equilibrium. The same applies if, due to only regional collective agreements, wages rise more slowly in one region than in another. In a monetary union, on the other hand, compensation can only take place via the movements of the factors of production (flexible jobs and flexible capital).

For the European Monetary Union, most studies come to the conclusion that there is currently no optimal currency area, as labor mobility in particular is too low. The monetary union therefore leads to an increase in real wages and thus a loss of competitiveness in the less productive EU countries, which contributed to the euro crisis . The European Central Bank's uniform monetary and interest rate policy was also unable to take sufficient account of the economic differences between the various member states and therefore had pro-cyclical effects in some countries .

However, some economists also point out that the monetary union itself can contribute to the creation of an optimal currency area, for example by increasing economic transactions between the member states through the common currency. In addition, some studies for the USA also come to the conclusion that it has not formed an optimal currency area for a long time or is still not forming it. The reason for the establishment of a common currency were therefore political rather than economic considerations.

European economic government

Another topic in the debate about the EMU is the demand for a European economic government , which traditionally was mainly demanded by the French government but rejected by Germany. However, “European economic government” is a catchphrase that can have different meanings depending on the context. In the discussion about the Maastricht Treaty of 1992, it mostly referred to the question of the independence of the European Central Bank : While in Germany the Bundesbank was kept away from any political access and was only committed to the goal of price stability , in France and other European countries it had the central banks were under the control of the government and had also been used for their economic policy goals. In the negotiations on the EMU, the stability-oriented German approach prevailed; however, the demand for a European economic government was retained later.

Common economic and industrial policy

A European economic government would enable a common fiscal and active economic policy in the EU, as desired by some of the political spectrum, but rejected by others. The EU cannot levy any taxes itself, and the European Union's own resources managed by the European Commission are neither so extensive nor so variably taxable that they would be suitable for an active economic policy. If an active economic policy is desired in principle or in special situations, this is a matter for the individual member states, which only coordinate with one another on a voluntary basis. The same applies to wage policy , as collective bargaining regulations are mostly limited to national law. France has therefore repeatedly called for such measures to be bundled more closely. However, this French position was mostly combined with the demand for a more active EU industrial policy , which was rejected in Germany as a step towards the wrong state interventionism in terms of regulatory policy .

The conflict became important in the financial crisis from 2007 , when all member states drew up national economic stimulus programs that were merely coordinated by the European Commission. Even if the direct disadvantage of members of other member states is not permitted within the framework of the European internal market , these different economic policy approaches could lead to imbalances between the individual EU states. In 2008, for example, Ireland's announced guarantee for its national banks put the other Member States under pressure to follow suit with similar means. Germany, on the other hand, was mainly accused by the French of having increased its productivity and competitiveness more than the other EU countries for several years through moderate wage increases, thereby contributing to imbalances.

During the euro crisis, calls for a European economic government increased by certain political currents and were also taken up by the President of the European Central Bank , Jean-Claude Trichet . Finally, the German government under Angela Merkel agreed to set up a European economic government. However, this should start at the level of the entire EU, not just the euro countries, and should be led by the European Council , not by the European Commission or by any new institutions to be created. A consensus of all EU member states would therefore continue to be required for economic policy decisions.

In order to facilitate coordination within the EU, there is also a proposal to unite various euro-relevant offices in the form of a double hat , namely that of the Commissioner for Economic and Monetary Affairs , the Chairman of the Council for Economic and Financial Affairs and the Chairman of the Euro Group . This proposal was put forward in a report by MEP Pervenche Berès and was approved by the European Parliament. Internal Market Commissioner Michel Barnier made a similar proposal in a Humboldt speech on Europe in May 2011. However, it would require a reform of the AEU Treaty and thus the approval and ratification of all member states.

Enforcement of the Stability and Growth Pact

Another problem facing the EMU is the implementation of the Stability and Growth Pact , which is intended to prevent excessive public deficits in the participating states ( see above ). The pact is considered to be ineffective, as the proposed sanction mechanism with fines would only worsen the budgetary position of the states concerned and, moreover, the Council for Economic and Financial Affairs repeatedly left violations of the pact unpunished.

After it became known in the wake of the Greek financial crisis in 2009/10 that Greece had reported incorrect budget data to the European Commission for several years, calls for better enforcement and more effective sanctions increased. The European Commission proposed the introduction of a "European Semester" , in which the member states have to present their budgets to the Commission and the other member states six months before the national parliaments vote on them. This is intended to give the Commission the opportunity to punish violations of the pact in advance. The proposal met with fierce criticism in some cases because it restricts national budgetary sovereignty, but was largely supported by the EU governments and approved by the Council for Economic and Financial Affairs on September 7, 2010. Since it could lead to an approximation of fiscal policy in the EU member states, this preliminary budgetary control is also often referred to under the term “European economic government” . It was used for the first time during the Hungarian EU Council Presidency in 2011 . The “European Semester” is supplemented by further measures to strengthen the economic and monetary union, such as the Euro Plus Pact or the so-called Six-Pack , a package of five regulations and a directive. It contains two laws that are intended to create framework conditions for reducing economic imbalances, one law that is intended to improve the transparency of Member State budget data and thus prevent their manipulation. Three other laws reform the Stability and Growth Pact.

In addition, there was intensive discussion of a changed sanctions regime, with the proposals reaching through to the withdrawal of voting rights in the Council of the EU and exclusion from the euro zone. However, these far-reaching plans, which were mainly represented by Germany and partly by France, met with rejection from other member states. On the other hand, the European Commission's proposal to cut agricultural and structural funds in countries with excessively high deficits was initially more widely accepted . This reduction would initially be "automatic", i.e. H. be done by the Commission itself and could only be reversed by the Council for Economic and Financial Affairs by a majority decision. This would strengthen the Commission compared to the previous procedure, in which sanctions only apply after a decision by the Council. However, changing the sanctions regime would definitely require an amendment to the FEU Treaty . A corresponding initiative was launched at the European Council summit in October 2010 ( see below ).

Crisis Response Mechanisms

Contrary to the stability-oriented treaties, some member states have overindebted their budgets to such an extent that these states have spread financial crises which, due to the economic and financial ties between the member states, increasingly affected all of the member states, starting with the Greek financial crisis in 2009/10.

This made another weak point of the EMU clear: There were no clear mechanisms provided for what to do if individual states were to become overindebted in a crisis.

Under the pressure of the spreading financial crisis, an emergency plan for Greece from loan guarantees from the other euro countries was agreed on March 25, 2010 and the establishment of a so-called European Stability Mechanism was decided on May 10, 2010 - initially limited to three years . This has a total volume of 750 billion euros and is based on a combination of loans from the EU budget , joint and several liability of the member states for this volume and a credit line from the International Monetary Fund (IMF). In order not to violate the no-bailout clause, a special-purpose vehicle, the European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF), was founded, which is not formally integrated into the EU legal framework. Nevertheless, Peter Gauweiler and a group led by Joachim Starbatty, among others, brought an action against the stabilization mechanism before the German Federal Constitutional Court . From July 5, 2011, the lawsuit was heard in the Federal Constitutional Court.

In the public debate on the European stabilization mechanism, it was criticized that there is an indirect threat of transforming the monetary union into a “transfer union” based on the example of the German state fiscal equalization scheme. In Germany in particular, this was mostly understood as a negative development because the financial equalization of the federal states would take away the incentives of recipient countries to reduce their deficits and thus increase their financial problems and cement their dependence on the donor countries. However, some German politicians emphasized that the stabilization mechanism only provides for loans and not transfers, which presupposes, however, that the ailing member states can also service the interest and repayment burden from these loans.

In the discussion about a solution to the Greek crisis, the German Finance Minister Wolfgang Schäuble in particular proposed a "European Monetary Fund" which, following the example of the International Monetary Fund, should help over-indebted states and at the same time drive structural reforms. The idea was welcomed by the European Commission , but on the other hand it also met with criticism: Such a fund would violate the no-bailout clause , as it “communitized” the debts of individual countries. In addition, it remained unclear why a dual structure of the IMF and the European Monetary Fund was necessary at all.

IMF President Dominique Strauss-Kahn called for greater monitoring of the member states, coupled with instruments to be able to organize transfers between the euro countries.

Finally, the issue of so-called euro bonds was also discussed, i.e. government bonds with joint liability, which would provide better and cheaper access to the credit market, especially for over-indebted member states. Larger and financially more stable countries such as Germany and France, without whose involvement in liability such a concept would hardly make sense, however, did not agree.

The establishment of a European or international state bankruptcy regime was also discussed, which would create clarity for creditors when states can no longer pay back loans.

Decision on a treaty reform in 2010

In mid-2010, a committee headed by Council President Herman Van Rompuy was set up to present a detailed proposal on the future sanctions regime for the Stability and Growth Pact during the Belgian EU Council Presidency in 2010 . On September 16, 2010, he presented an interim report to the European Council, which met with general approval after the finance ministers had already decided to introduce the “European Semester” for better mutual budget control.

Van Rompuy's final report was adopted at the October 2010 summit. Shortly before this summit, German Chancellor Angela Merkel and French President Nicolas Sarkozy presented joint proposals, with the idea of withdrawing member states' voting rights in the Council of the European Union in particular causing controversial discussions. Ultimately, Van Rompuy was asked at the summit, proposals for a "limited treaty reform" of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union according to Art. 48 para. 6 to draw up EU treaty to set up a "permanent crisis mechanism" of 2013 of the place interim stabilization mechanism should occur.

At the summit of the European Council on December 16, 2010, Van Rompuy presented a concrete proposal for a treaty reform. The no-bailout clause in Art. 125 TFEU remained unaffected; Instead, Art. 136 TFEU is to be expanded to include a paragraph that enables the states of the euro zone to set up a permanent European Stability Mechanism (ESM). This should be able to be activated in order to “secure the stability of the euro zone as a whole in an emergency”. Grants under the permanent stabilization mechanism are said to be "subject to strict conditions". This treaty amendment now has to be ratified by the member states and should come into force on January 1, 2013. In this case, the permanent stabilization mechanism could immediately replace the stabilization mechanism, which is limited to three years and which was decided in the course of the euro crisis . Its precise structure was decided by the finance ministers of the Eurogroup at the end of March 2011 and includes, among other things, a procedure according to which private creditors - primarily banks - are involved in the rescue in future debt crises in EMU member states, which is in fact the case corresponds to the German proposal for a state insolvency order .

A revision of the sanction mechanism in the Stability and Growth Pact was also discussed. In addition to the proposal to withdraw voting rights for states with excessive deficits, the Commission proposal plays a role, according to which sanctioning mechanisms in the event of excessive indebtedness on the part of member states should in future take effect "automatically", i.e. without a prior decision by the Council. This proposal, which would have made a treaty amendment necessary, was seen by the Commission and the European Parliament as necessary for reform, but rejected by France and other Member States and therefore not taken up by the European Council. On March 15, 2011, the Eurogroup agreed on a tightening of the Stability Pact, which provides for higher penalties and an obligation to give reasons for the Council if it does not initiate sanctions proceedings despite a breach. Automatic sanction mechanisms have not been introduced.

Germany and France also presented early February 2011, proposals for improved cooperation between the Member States of the euro zone in the fiscal area in front of, among other things, an alignment of corporate tax rates and wage policies as well as a uniform retirement age provision. However, other member states reacted negatively to some of these proposals. On the basis of the Franco-German initiative, Van Rompuy worked out a “Pact for the Euro”, which was agreed in advance on March 11, 2011 by a summit of the heads of state and government of the Euro Group . However, the pact only contains declarations of intent, no new legal obligations for the member states. Since some non-euro states also agreed to carry out the reforms envisaged in the pact, it was finally given the name “ Euro Plus Pact ”.

On 24./25. In March 2011, the European Council approved the overall package of reforms for the EMU. It includes the European Stabilization Mechanism, the tightening of the Stability and Growth Pact and the Euro Plus Pact .

Possible reform of the EMU through a European Convention

According to Art. 48 , the Treaty on European Union and the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union can be amended in accordance with the ordinary or a simplified amendment procedure. The ordinary procedure provides for a European Convention to be convened by the President of the European Council .

In spring 2012, a European convention was supposed to tackle a reform of the economic and monetary union. This became known on the sidelines of a European Council meeting on October 23, 2011. At the center of the reform should be the design of a fiscal union that allows direct intervention in the tax and budgeting of euro member countries when they receive financial help from the partners. Such a fiscal union would bundle a number of individual measures and anchor them institutionally, such as the Euro Plus Pact , the European Semester or the regulations of the so-called "Six-Pack" (see above).

In December 2012, however, the proposals for a contractual reform - and thus for a convention - were postponed for the time being.

literature

- Ralph Edgar Berens: Europe on the way to a transfer union? Bank rescue & state rescue & euro rescue and no end - an inventory from an economic and legal point of view . Lit, Berlin 2014, ISBN 978-3-643-12492-0 ( review in the Annotated Bibliography of Political Science ).

- Egon Görgens, Karlheinz Ruckriegel, Franz Seitz: European monetary policy. Theory, empiricism, practice . 4th, completely revised edition. Lucius & Lucius, Stuttgart 2004, ISBN 3-8282-0286-1 (UTB, vol. 8285, ISBN 3-8252-8285-6 ).

- Germán Gutiérrez, Thomas Philippon (2018): How EU Markets became more competitive than US Markets: A Study of institutional Drift. NBER Working Paper, No. 24700

- Harold James : Making the European Monetary Union , with a foreword by Mario Draghi . Harvard University Press, Cambridge (Massachusetts) 2012, ISBN 978-0-674-06683-0 .

- Claus Köhler: Short Economic Commentary: Contractual Basis of the European Monetary Union . Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1999, ISBN 3-428-09655-X .

- Wolfgang J. Mückl (Ed.): The European Monetary Union: Problems and Perspectives . Schöningh, Paderborn 2000, ISBN 3-506-73391-5 (conference proceedings of the section for economics and social sciences of the Görres Society).

- Werner Polster: European Currency Integration. From the payments union to the monetary union . Metropolis, Marburg 2002, ISBN 3-89518-382-2 (diss.).

- Franz-Ulrich Willeke: Germany, EU paymaster , OLzog Verlag, Munich 2011

Web links

- The Latin Monetary Union as the historic precursor to the euro WELT-Online, July 30, 2012

- Economic and Monetary Union on the homepage of the European Central Bank

- Economy and currency. In: EUR-Lex, Topic Summary - Summaries of EU Legislation. Publications Office of the European Union

- iconomix: European Monetary Union. Accessed on January 28, 2013 (learning module on European Monetary Union).

- Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung , Working Group Europe (2010): The Future of the European Economic and Monetary Union (PDF; 143 kB).

- Arne Heise / Özlem Görmez Heise (2010): On the way to a European economic government on the homepage of the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung (PDF; 171 kB).

- Susanne Mundschenk, Daniela Schwarzer, Stefan Collignon: The Monetary Union - Opportunity for Europe: Manual for the European Monetary Union on the homepage of the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung

- Björn Hacker and Till van Treeck (2010): How influential is European governance? Reformed Stability and Growth Pact, Europe 2020 Strategy and “European Semester” , Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, 180 kB PDF.

- Stefan Collignon (2010): Democratic requirements for a European economic government , Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, PDF, 650 kB.

- Markus Reupke: The economic and monetary union: the importance for the European Union under political and international consideration in the Google book search

Individual evidence

- ↑ EUR-Lex, Text html: EMU in English and Dutch, UEM in Romance languages

- ↑ ECB: The three stages of EMU: 1990, 1994 and 1999

- ↑ See also Susanne Mundschenk, Daniela Schwarzer, Stefan Collignon: The Monetary Union - Opportunity for Europe: Handbook on the European Monetary Union ( Memento of May 27, 2009 in the Internet Archive ), ed. from the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung , Department of International Dialogue, Bonn 1999, ISBN 3-86077-797-1 .

- ↑ See Egon Görgens / Karlheinz Ruckriegel / Franz Seitz: European monetary policy. Theory, Empiricism, Practice , 4th, completely revised edition, Stuttgart (Lucius & Lucius) 2004, ISBN 3-8282-0286-1 (= UTB, vol. 8285, ISBN 3-8252-8285-6 ), p. 20 ff.

- ↑ See Richard E. Baldwin / Charles Wyplosz: The Economics of European Integration , Maidenhead, Berkshire (McGraw-Hill Education) 2004, ISBN 0-07-710394-7 , pp. 358 f. And p. 363.

- ↑ Dammann, The Right to Leave the Eurozone, Texas International Law Journal 126, Vol. 48 (2013), http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2262873

- ↑ See also Susanne Mundschenk, Daniela Schwarzer, Stefan Collignon: The Monetary Union - Opportunity for Europe: Handbook on the European Monetary Union, Chapter 2.2 ( Memento of October 12, 2008 in the Internet Archive ), ed. from the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung , Department of International Dialogue, Bonn 1999, ISBN 3-86077-797-1 .

- ↑ See EUabc.com: Eurozone and EUabc.com: Euroland .

- ↑ Federal Law Gazette 2014 II p. 864

- ↑ https://ec.europa.eu/info/publications/economy-finance/fiscal-sustainability-report-2018_en , accessed on November 26, 2020

- ^ Europa Digital 2003: Franco-German alliance against the Stability Pact ( Memento of October 21, 2007 in the Internet Archive ).

- ^ Hans-Peter Schwarz : Helmut Kohl. A political biography . Deutsche Verlagsanstalt, Munich 2012, 1052 S, Part V, Section “Euro-Fighter” ISBN 978-3-421-04458-7 .

- ↑ See German Bundestag , Infobrief Bilateral Financial Aid for Greece - Compatibility with Article 125 TFEU ( Memento of June 1, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 180 kB).

- ↑ Financial Times Deutschland , May 17, 2010: ECB buys government bonds for EUR 16.5 billion ( Memento of May 20, 2010 in the Internet Archive ); Der Spiegel , May 29, 2010: Bundesbankers suspect a French plot .

- ^ Die Welt , May 31, 2010: Bundesbank boss Weber criticizes the ECB .

- ^ Daniela Schwarzer, Ten Years of Governance of the Eurozone. In: integration 1/2009, pp. 17–32, here pp. 24 f. (PDF file; 113 kB).

- ^ Daniela Schwarzer, Ten Years of Governance of the Eurozone. In: integration 1/2009, pp. 17–32, here pp. 27 f. (PDF; 113 kB)

- ↑ Composition and statutes of the Economic and Financial Committee. Summary of Legislation. In: EUR-Lex . Publications Office of the European Union , accessed on 11 October 2021 .

- ↑ Eurozone countries should speak with one voice, Juncker says. EUobserver, April 15, 2008 (English).

- ↑ Gabriele Clemens et al., History of European Integration , Paderborn 2008, pp. 58 and 88.

- ↑ See Gerhard Brunn, Die Europäische Einigung von 1945 bis today , Stuttgart 2002 / Bonn 2004, p. 218; Gabriele Clemens et al., History of European Integration , Paderborn 2008, p. 203.

- ↑ See Gerhard Brunn, Die Europäische Einigung from 1945 to today , Stuttgart 2002 / Bonn 2004, p. 214 ff.

- ↑ Gabriele Clemens et al., History of European Integration , Paderborn 2008, p. 202.

- ↑ See Gerhard Brunn, Die Europäische Einigung from 1945 to today , Stuttgart 2002 / Bonn 2004, p. 217.

- ↑ Gabriele Clemens et al., History of European Integration , Paderborn 2008, p. 205.

- ↑ See Gerhard Brunn, Die Europäische Einigung from 1945 to today , Stuttgart 2002 / Bonn 2004, p. 221 ff.

- ↑ See Gerhard Brunn, Die Europäische Einigung von 1945 bis today , Stuttgart 2002 / Bonn 2004, p. 226 f.

- ↑ Gabriele Clemens et al., History of European Integration , Paderborn 2008, p. 208.

- ↑ Gabriele Clemens et al., History of European Integration , Paderborn 2008, p. 207.

- ↑ Cf. Gerhard Brunn, Die Europäische Einigung from 1945 to today , Stuttgart 2002 / Bonn 2004, p. 262 f.

- ↑ Cf. Gabriele Clemens et al., History of European Integration , Paderborn 2008, p. 225.

- ↑ See Gabriele Clemens et al., History of European Integration , Paderborn 2008, p. 226.

- ↑ Cf. Gabriele Metzler , "Abolish the pound and you abolish Britain". Pound sterling, Bank of England and British identity in the 20th century , in: Bernhard Löffler (Ed.): The cultural side of currency. European currency cultures , monetary value experiences and central bank systems in the 20th century , Munich 2010, pp. 169–197.

- ↑ Peter Huber: Monetary Union: The end of the "German atomic bomb" , article from November 30, 2010 in the online portal Die Presse.com , accessed on July 10, 2011

- ↑ Mitterrand asked for euros in return for the unit. In: The mirror . September 26, 2010, accessed February 24, 2015 .

- ↑ See Markus Reupke, Die Wirtschafts- und Monetary Union. The importance for the European Union under political and international consideration. ( Page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Oldenburg 2000, p. 33. (PDF) (currently not available)

- ↑ Cf. Gerhard Brunn, Die Europäische Einigung von 1945 bis today , Stuttgart 2002 / Bonn 2004, p. 288 f.

- ↑ See Gerhard Brunn, Die Europäische Einigung from 1945 to today , Stuttgart 2002 / Bonn 2004, p. 291.

- ↑ Cf. Gerhard Brunn, Die Europäische Einigung von 1945 bis today , Stuttgart 2002 / Bonn 2004, p. 292 f.

- ↑ See European Central Bank : Economic and Monetary Union (EMU)

- ^ On the following, see Helmut Wagner: European Economic Policy - Perspectives of a European Economic and Monetary Union , 2nd revised and expanded edition, Berlin, 1998, p. 11 ff.

- ^ Daniela Schwarzer, Ten Years of Governance of the Eurozone (PDF file; 113 kB), in: integration 1/2009, pp. 17–32, here p. 18.

- ↑ See inflation development in Germany since 1980 on finanznachrichten.de.

- ↑ Decision of the Council of 3 May 1998 under Article 109j (4) of the Treaty

- ↑ nzz.ch: EU summit clears the way for Estonia to join the euro zone. Retrieved June 17, 2010 .

- ↑ DEVISEN / EU sets euro exchange rate for Estonia ( Memento from August 4, 2012 in the web archive archive.today )

- ^ Daniela Schwarzer, Ten Years of Governance of the Eurozone (PDF file; 113 kB), in: integration 1/2009, pp. 17–32, here pp. 21 f.

- ^ Die Presse , July 16, 2009: Mini majority for Iceland's EU proposal .

- ↑ Café Babel, June 2, 2009: Anders Fogh Rasmussen: “The financial crisis has had an enormous impact on the Danes' enthusiasm for Europe” ( Memento from January 15, 2010 in the Internet Archive ); EUobserver , March 3, 2011: Denmark eyeing referendum on euro .

- ↑ See Robert A. Mundell: A Theory of Optimum Currency Areas, in: The American Economic Review 51.4 (1961), pp. 657-665.

- ↑ See Richard Baldwin / Charles Wyplosz: The Economics of European Integration , Maidenhead, Berkshire (McGraw-Hill Education) 2004, ISBN 0-07-710394-7 , p. 340 ff .; Paul Krugman / Maurice Obstfeld: International Economy. Theory and Politics of Foreign Trade , 7th edition, Pearson Studium, Munich and others. 2006, ISBN 978-3-8273-7199-7 ISBN 3-8273-7199-6 , p. 727 ff.

- ↑ Cf. Francisco P. Mongelli: "New" views on the optimum currency area theory: what is EMU telling us? , European Central Bank , Frankfurt am Main 2002 (= Working paper series, No. 138), European Central Bank (PDF; 544 kB).

- ↑ Cf. Die Welt , May 16, 2010: It took the USA 150 years to create an optimal common currency area .

- ↑ a b c Frankfurter Allgemeine , June 15, 2010: A semblance of unity .

- ↑ Tagesschau , November 26, 2008: The economic stimulus packages in the individual EU countries .

- ↑ Die Welt , October 4, 2008: Most important EU states want to support banks .

- ^ Die Zeit , March 15, 2010: Neighbors complain about low wages in Germany .

- ^ Spiegel online , May 31, 2010: Trichet calls for European economic government .

- ↑ Financial Times Deutschland , June 15, 2010: European Economic Government: Merkel smashes minimal consensus against Sarkozy ( memento of June 17, 2010 in the Internet Archive ).

- ↑ EurActiv , October 15, 2010: Parliament will support plan for “Mr” or “Mrs Euro” ( Memento of January 2, 2013 in the web archive archive.today ).

- ↑ EurActiv , 10 May 2011: Barnier dreams of the President of Europe .

- ↑ EurActiv , May 12, 2010: The European Semester ( Memento of May 14, 2010 in the Internet Archive ).

- ↑ EurActiv , May 14, 2010: Vigorous discussion about EU budgetary control ( Memento of May 16, 2010 in the Internet Archive ).

- ↑ EurActiv , 7 September 2010: Finance ministers decide on “European semester” ( memento of 6 October 2011 in the Internet Archive ).

- ↑ Six-Pack: Reform of the Stability Pact confirmed

- ↑ EurActiv , June 18, 2010: British exemption in EU economic government ( Memento of September 19, 2011 in the Internet Archive ).

- ↑ EurActiv , July 1, 2010: Brussels presents new economic management plans ( Memento of September 16, 2011 in the Internet Archive ).

- ↑ EurActiv , July 6, 2010: ECB supports treaty amendment for economic governance of the EU ( Memento of August 27, 2010 in the Internet Archive ).

- ↑ Manager-Magazin , May 10, 2010: EU support plan in the cabinet on Tuesday .

- ^ Frankfurter Allgemeine , July 7, 2010: Warning of transfer union .

- ↑ http://www.euractiv.de/fileadmin/images/Murswiek_Gauweiler_Karlsruhe.pdf

- ↑ See for example Frankfurter Allgemeine , April 17, 2010: May Germany pay for Greece? ; Die Welt , May 2, 2010: The EU will become a transfer union with immediate effect .

- ^ German Bundestag , May 12, 2010: Government: No entry into the euro transfer union ( Memento from July 19, 2010 in the Internet Archive ); EurActiv , 6 May 2010: Federal Council on Greece: “No transfer union!” ( Memento from 9 October 2010 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Frankfurter Allgemeine , March 7, 2010: Schäuble is thinking of the European Monetary Fund .

- ↑ Süddeutsche Zeitung , May 12, 2010: Well-monitored transfer union .

- ↑ Cf. Focus , May 20, 2010: “The time is ripe for state bankruptcies” ; Neues Deutschland , May 14, 2010: Controversial issue: an orderly bankruptcy as a way out of the Greek crisis? .

- ^ EUobserver , May 21, 2010: Van Rompuy task force agrees need for budgetary sanctions. (English).