Greek sovereign debt crisis

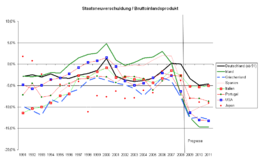

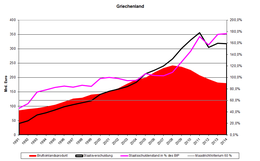

The Greek national debt crisis (also Greek financial crisis and Greek depression ) is a crisis of the state budget and the economy of the Republic of Greece that has been ongoing since 2010 . After the elimination of the national currencies and the associated exchange rate mechanism after the introduction of the euro, the development of suitable internal adjustment mechanisms in the euro countries failed. Just one year before 2001 were made accession to the euro zone which was Greece's sovereign debt 104.4% of gross domestic product (GDP). During the global financial crisis from 2007 and the bank rescue program of the Karamanlis government, the Greek national debt ratio rose further from 107.2% (2007) to 129.7% (2009).

In October 2009, the newly elected Prime Minister Giorgos A. Papandreou (PASOK) announced upwardly revised data on debt (from 3.7 to 12.7% of GDP) and other poor economic data. Methodological deficiencies of the Statistical Office of Greece ( ESYE ) and possible political influence on the statistics prompted this correction. The new data resulted in Greek government bond yields rising sharply. In the same year, Papandreou asked IMF boss Strauss-Kahn to set up an aid program for Greece, which the latter refused in order to refer the prime minister to the EU partners. Together with the IMF, they prepared a much larger loan package, which Papandreou originally only wanted to accept after a referendum, which some of the most important euro partners rejected. The Sarkozy and Merkel governments demanded that Greece either accept the loan terms without a vote or leave the euro zone. Since the government was unable to repay due loans , Papandreou gave in, and Greece applied for the three-year aid package on April 23, 2010 without a prior referendum.

An IMF loan of 30 billion euros for Greece was initially increased by the EU to a total of 110 billion euros and declared as a measure to rescue Greece and the euro. While the IMF loans for Greece (also called "emergency loans") have only been adjusted slightly to 32 billion euros to date (as of May 2018) due to inflation, the EU and ECB increased the share of the euro bailout (so-called "emergency guarantees") of the meanwhile three loan packages despite concerns of the successively involved Prime Ministers Papandreou, Samaras and Tsipras to 290 billion euros (= euro rescue package ). The financial framework granted by the three institutions involved - the so-called “Troika” - is now ten times as high as the aid program launched by the IMF, at 322 billion euros. Of this, 277.6 billion euros were ultimately paid out (as of September 2018). 31.9 billion euros in IMF loans went to the Greek state and 245.7 billion euros in so-called EU guarantees went to European banks.

In March 2015, the European Central Bank (ECB) bought bonds from euro countries . The “institutions” and the Greek government decided, among other things, to make extensive budget cuts. The measures included, among other things, wage cuts, for example in the public service and the minimum wage , general budget cuts and an increase in VAT . In addition, privatizations were carried out. Measures to improve the Greek administration were also initiated. These include the implementation of the administrative reform under the Kallikratis program in May 2010 , the numerical recording of all people working for the state and the review of pension payments to those who may have already died. The amalgamation of the numerous local land registries (υποθηκοφυλάκειο "mortgage office, land registry"), which has been ongoing for years, to form a national cadastre for all around 3.6 million properties should be completed by 2020.

Greece was in recession from 2008 and by 2013 lost around 26 percent of its real (price-adjusted) gross domestic product (GDP). In 2014 there was a minimal increase of 0.4% of real GDP. Despite the haircut in 2012 and despite or due to measures imposed by the Troika, the relative debt level increased from 107.2% to 177.1% of the shrinking GDP from 2007 to 2014. Greece has been in deflation since March 2013 . Unemployment has risen sharply and was around 26 percent in 2014; the problems in the health sector, among other things, had risen sharply.

On January 25, 2015 there was a change of government in Greece . The new ruling party SYRIZA initially continued negotiations on the second program for five months. On the night of June 27, 2015, Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras broke off negotiations and called a referendum . The very next day parliament decided by an overwhelming majority to hold the referendum. As a countermeasure, ECB boss Mario Draghi immediately stopped the flow of capital to the Greek banks, so that Finance Minister Yanis Varoufakis was forced to introduce capital controls. In June 2015, international transfers were placed completely under state supervision and only approved in exceptional cases. Cash withdrawals from banks have been restricted to € 60 per day. These restrictions mainly affected the self-employed and companies; the majority of the population supported their government's referendum with 61.3% no votes against the ECB and the EU partners. As a result, Tsipras surprisingly made a U-turn on election night, which Finance Minister Varoufakis did not want to support and resigned.

On July 12, 2015, the heads of state and government of the euro zone unanimously agreed on the framework conditions for starting negotiations on a third aid program, and Athens received a bridging loan of 7.16 billion euros from the EU bailout fund, which had not been used for several years EFSM . The euro finance ministers approved the third aid package on August 19, 2015. The third package was worth 86 billion euros and expired in August 2018. It was processed through the ESM . On August 20, Alexis Tsipras announced his resignation in order to legitimize the revision of his position through re-election. In the parliamentary elections in Greece in September 2015 , Tsipras emerged again as the winner and continued the coalition with the ANEL party.

The third aid program for Greece, which expired in August 2018, was discontinued. The Prime Minister had closed it early, even before the funds provided were used up. Of the originally agreed 86 billion euros, Greece finally accepted to pass only 55 billion euros through to the banks. Instead, Tsipras announced that his country would be able to do without European aid programs in the future. The final payment to Athens of 15 billion euros and a postponement of loan repayments by ten years were agreed by the finance ministers of the euro area.

| date | Fitch | S&P | Moody's | source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15th Mar 2007 | A1 | |||

| Oct 29, 2008 | A1 | |||

| Dec 8, 2009 | BBB + | |||

| December 16, 2009 | BBB + | |||

| Dec 22, 2009 | A2 | |||

| Apr. 27, 2010 | BBB− | BB + / B | A3 | |

| June 14, 2010 | Ba1 | |||

| 7th Mar 2011 | B1 | |||

| 30th Mar 2011 | BB− | |||

| May 9, 2011 | B. | |||

| May 20, 2011 | B + | |||

| June 1, 2011 | Caa1 | |||

| June 14, 2011 | CCC | |||

| July 13, 2011 | CCC | |||

| July 25, 2011 | Approx | |||

| July 27, 2011 | CC | |||

| Feb. 22, 2012 | C. | |||

| Feb. 27, 2012 | SD | |||

| 3rd Mar 2012 | C. | |||

| 9 Mar 2012 | RD | |||

| 13 Mar 2012 | B- | |||

| May 2, 2012 | CCC | |||

| May 17, 2012 | CCC | |||

| Dec 6, 2012 | SD | |||

| December 18, 2012 | B- | |||

| May 14, 2013 | B- | |||

| Nov 29, 2013 | Caa3 | |||

| ... | ... | ... | ... | |

| Aug 1, 2014 | Caa1 | |||

| Sep 12 2014 | B. | |||

| Jan. 16, 2015 | B. | |||

| Apr 15, 2015 | CCC + | |||

| Apr. 29, 2015 | Caa2 | |||

| May 15, 2015 | CCC | |||

| June 11, 2015 | CCC | |||

| June 29, 2015 | CCC- | |||

| June 30, 2015 | CC | |||

| July 1, 2015 | Caa3 | |||

| Aug. 18, 2015 | CCC | |||

| Jan. 22, 2016 | B- | |||

| June 23, 2017 | Caa2 | |||

| Aug. 18, 2017 | B- | |||

| Jan. 19, 2018 | B. | |||

| February 16, 2018 | B. | |||

| Feb. 21, 2018 | B3 | |||

| June 25, 2018 | B + | |||

| Oct. 8, 2018 | BB- | |||

| 1st Mar 2019 | B1 |

Origin and course

Until the change of government in 2009

Greece joined the euro area on January 1, 2001. In a 2004 report, Eurostat found that the statistical data sent by Greece might not be correct. This was attributed to the fact that the Statistical Office of Greece ( ESYE ) had incorrectly evaluated the data available to it and the authorities and ministries had supplied the office with incorrect data. Against this background, Eurostat published a report on the revision of the Greek deficit and debt figures in November 2004, according to which incorrect figures were reported in eleven individual cases in the years prior to 2004.

In January 2010 the European Commission reported again in its “Report on the Statistics of Greece” on methodological deficiencies in financial statistics at ESYE, a lack of political control and political influence on statistical data. Since July 2010, ELSTAT has been a new, non-governmental authority for statistics.

According to reports in Spiegel and the New York Times , US banks such as Goldman Sachs and JP Morgan had helped various euro countries such as Italy and Greece in the past ten years to conceal the extent of their national debt . Newly taken out loans were booked as currency swaps , which were not included in the national debt. The use of financial derivatives for public finance was not regulated until 2008. Following regulation by Eurostat in 2008, the Greek government failed to comply with reporting requirements when late reporting of such transactions was requested.

According to a report by Bloomberg Business , the Greek government borrowed more than 2.8 billion euros through a currency swap deal signed with Goldman Sachs in 2001 . With the help of fictitious exchange rates, about two percent of the Greek national debt could be hidden in the balance sheet with this transaction. However, the deal turned out to be unfavorable for the Greek state, probably due to its lack of transparency and complexity, so that a renegotiation was scheduled just three months after the deal, which led to a deal with inflation-linked derivatives . However, these subsequently turned out to be also disadvantageous for the Greek state, so that in August 2005 the Greek government negotiated with Goldman Sachs about the repurchase of the entire bonds by the Greek central bank . The repayment of these derivatives ultimately resulted in an amount of 5.1 billion euros, for the financing of which over-the-counter interest rate swaps were taken out. Allegedly, Goldman Sachs received € 600 million to carry out this deal. Other reports say that expected future income, for example from airport fees and lottery winnings, has been transferred.

From the change of government to the outbreak of the crisis

In the parliamentary elections on October 4, 2009 , the PASOK party won an absolute majority of the parliamentary seats with a 43.9% share of the vote . Two days later, Giorgos Papandreou was sworn in as the new Prime Minister. The increases in social spending promised by PASOK to the voters could not be financed. On October 20, 2009, the new finance minister, Giorgos Papakonstantinou , declared that the budget deficit in 2009 would not amount to around 6 percent of GDP, as stated by the previous government, but rather 12 to 13 percent. It thus exceeded the agreed 3 percent new borrowing limit by far. The promise made by the previous government in April 2009 as part of ongoing deficit penal proceedings to reduce its 2009 national deficit to 3.7% (of GDP) could therefore not be honored. One month after his election as prime minister, Papandreou then contacted IMF chief Strauss-Kahn and, according to his own statements, asked for technical support, which the IMF chief refused and referred to the EU. Strauss-Kahn later presented the conversation in the press in a different light; at that time it was about financial aid. Around the same time, in an interview with ALTER , the future chairman of the ND Antonis Samaras accused the new government of having changed the planned budget for 2009/2010 in such a way that expenditure in 2010 was anticipated and revenues were postponed from 2009 to 2010. As a result of these targeted (but legal) budget changes, the deficit in 2009 jumped from the originally calculated approx. 8% to 12%. The Supreme Court dealt with the matter in 2016 and overturned a previous court judgment in its decision 1331/2016. In doing so, he followed the prosecution's complaint that the Papandreou government had artificially corrected the national deficit upwards in 2009 and the head of the Greek statistics agency ELSTAT covered this correction in order to consciously drive Greece into the memorandum.

The government in Athens agreed with the EU to report to Brussels every two to three months on its savings successes. The ambitious goal set was that Greece wanted to push net new indebtedness by 2012 below the three percent of gross domestic product stipulated in the Stability and Growth Pact . At a special EU summit on February 11, 2010 in Brussels, Papandreou was called upon to implement drastic austerity policies in order to avert national bankruptcy. The expectation of the summit participants that expressions of solidarity with Greece would be sufficient to calm the financial markets was not fulfilled. After long controversies about the design of the aid measures, the heads of state and government of the euro countries agreed at the end of March 2010 to support Greece financially.

| Financiers | accept | Paid | Transfer to 2nd program |

|---|---|---|---|

| Euro countries | 77.3 | 52.9 | 24.4 |

| IMF | 30.0 | 20.1 | 9.9 |

| total | 107.3 | 73.0 | 34.3 |

| Source: EU Commission. When it became known that the Troika was planning a second loan package, the Prime Minister prematurely ended the current first one. He thus prevented the transfer of the remaining € 24.4 billion and waived a € 9.9 billion loan, instead he announced a referendum. It was only after Papandreou was overthrown that the EU was able to put together the second package. The refused aid funds totaling € 34.3 billion were contractually agreed upon by the Samaras government following the signing of the second loan package. | |||

Impending insolvency and appeal for help to the IMF and EU

After Strauss-Kahn rejected IMF support and the subsequent lengthy negotiations with the troika made up of IMF, EU and ECB, the risk premiums for long-term Greek government bonds climbed to new record levels. Finally, on April 23, 2010, the Greek government officially applied for financial aid. Under the leadership of Strauss-Kahn, the troika reached an agreement on January 1st and 2nd. May 2010 with Papandreou on an IMF loan of € 30 billion and a guarantee from the EU countries of € 77.3 billion, this time on condition that Greece implements a rigorous austerity program. In order to support banks that hold Greek government bonds, the European Central Bank has accepted Greek government bonds in full face value as collateral since May 3, 2010 , although their creditworthiness is rated as low by the rating agencies.

However, the aid decided for Greece was not enough to calm the markets over the long term. The risk premiums for Greek government bonds continued to rise. In view of these developments, the European heads of state and government agreed at a summit meeting (on May 7th, supplemented by a meeting of finance ministers on May 9th and 10th, 2010) on the establishment of the European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF), which, if necessary, would address the impending insolvency of a Member of the euro zone.

Economic and Political Consequences of the First Memorandum

The economic situation deteriorated as a result; Insolvencies in the private sector and the number of unemployed (quota increase from 8.5% to 12%) increased. Investments, GDP and thus also the tax revenues based on them fell. The risk premiums on Greek government bonds determined on the financial market rose again and in September 2010 almost reached the level of the peak of the crisis in May.

In Greece, economic output contracted by 4.5% in 2010 ( recession ). To counteract this, the Greek government asked the European Commission to simplify the release of certain funds for Greece from the EU structural funds . These funds of 15.3 billion euros could not previously be called up by Greece, as the country cannot raise the necessary contribution due to the austerity measures.

In the first half of 2011, protests against the austerity measures in Greece increased. The then largest opposition party Nea Dimokratia (ND) as well as several other smaller opposition parties turned against the downsizing of the civil service and the announced privatization of state enterprises. Already in November 2010 this led to a split from the ND, in which reform-minded party members founded the new party Dimokratiki Symmachia . There were also conflicts within the government faction of PASOK over the austerity course, which some MPs refused to support. On May 27, the Greek parliament voted against a government proposal for further austerity measures. The EU then demanded a bipartisan consensus from the Greek parliament on debt reduction and made further aid dependent on the Greek parliament adopting a new austerity package. The European People's Party also increased the pressure on its member party ND.

At the end of June 2011, the Greek Prime Minister Papandreou reshuffled his cabinet and appointed, among other things, the previous Defense Minister Evangelos Venizelos as Minister for Economic Affairs and Finance. On June 29, the Greek parliament voted against the votes of most of the ND MPs for a new austerity package that the member states had named in the European Council as a prerequisite for further aid measures.

In the first half of 2011, the Greek new debt amounted to almost 14.7 billion euros - planned for the whole of 2011 was around 16.7 billion euros. Greece had debts of more than 350 billion euros at the time. At the end of 2010, the Greek national debt was 142.8% of GDP; for the end of 2011 the EU Commission expected it to be around 157.7% of GDP.

At a special summit on July 21, 2011, the euro countries agreed on a second rescue package for Greece, despite Papandreou's concerns. Because of the far-reaching consequences for the citizens of this second, significantly larger borrowing, Papandreou once again announced that it would let the citizens decide in a referendum on the EU way out of the crisis and stopped taking up the euro rescue loans. The EU saw no alternative to its path and expressed massive concerns about the referendum. It finally refused to support Papandreou, so that Papandreou withdrew the referendum and resigned as prime minister. Just two weeks later (November 10, 2011) a government of EU technocrats was installed in Athens for six months and immediately called off the next tranche of the first loan package. The rescue package was then stopped (after only 73 of the planned € 107.3 billion); instead, the EFSF and the IMF prepared the second loan package amounting to € 130 billion plus haircut. Shortly after it was signed by the new Prime Minister Antonis Samaras, it turned out that he had to call up the 34.3 billion of his predecessor that had not been used

Consequences of the first memorandum for democracy

On May 1, 2010, Giorgos Papandreou signed a memorandum with the three institutions of the Troika, IMF, EU and ECB. Under pressure from the EU partners, he had previously waived a referendum, and in addition to the IMF loan for Greece that had been applied for, a much larger package to rescue banks in other EU countries (so-called euro rescue) was agreed. For this, on the Day of German Unity in 2010, he and Wolfgang Schäuble received the Quadriga Prize for his “Power of Truthfulness”. Papandreou's laudation was given by Josef Ackermann .

In the next year, Schäuble announced a second package to rescue the euro without prior consultation, whereupon Papandreou - regardless of the price he had just acquired - immediately put all further money transfers for European banks on hold. When he announced on October 30, 2011 that he wanted to hold a “binding” referendum in the same year, the Prime Minister stood up with the words: “We trust the citizens, we trust their judgment, we trust their decision. It is an act of democracy. We have a duty to promote the role and responsibility of citizens “openly against the agreements. Shortly thereafter, he was forced to resign under domestic and foreign political pressure and a former Goldman Sachs employee and ECB vice chairman was installed without election. The Quadriga Prize has not been awarded since 2010 .

Both the provisions of the credit agreements and the form in which they are implemented have met with legal criticism. Parliamentary participation - the Greek constitution provides for a three-fifths majority for the ratification of such far-reaching international treaties - was restricted. A law was passed with a simple majority, according to which the contracts are valid from their signature. In the opinion of the constitutional lawyer Giorgos Kassimatis, this procedure constitutes a breach of the constitution. In his opinion, the credit agreements violate the basic democratic and social rights and property rights of Greek citizens as well as state sovereignty, for example through the complete binding of the entire Greek state assets . An expert opinion prepared by the Bremen legal scholar Andreas Fischer-Lescano on behalf of several European trade union organizations primarily problematizes the lack of legal binding of the EU bodies when concluding loan agreements. The constitutional lawyer Kostas Chrysogonos criticizes the fact that in the course of the implementation of the conditions of the loan agreements laws are increasingly being passed by decree and that emergency law is used in labor disputes.

Parliamentary elections 2012 and further developments

| Financiers | accept | Paid |

|---|---|---|

| EFSF | 144.6 | 130.9 |

| IMF | 19.8 | 11.8 |

| total | 164.4 | 142.7 |

| Source: BMF / EFSF; Status: March 2018 | ||

Early parliamentary elections were held in Greece on May 6, 2012 . The two large people's parties, Nea Dimokratia (ND) and the social democratic Panellinio Sosialistiko Kinima (PASOK), suffered a sharp drop in votes; both together did not have an absolute majority or government majority in parliament. For the first time, the neo-Nazi and racist Chrysi Avgi entered parliament, as did the right-wing populist Anexartiti Ellines and the left-wing Dimokratiki Aristera . The radical left SYRIZA led by Alexis Tsipras surprisingly became the second largest party. Tsipras' attempt to form a government failed; then Evangelos Venizelos , Chairman of PASOK and Minister of Finance, got the job. His attempt also failed.

Andonis Samaras formed a new government ( Samaras cabinet ) shortly after the general election on June 17th . It was supported by three parties (Conservatives (ND) Socialists (Pasok) and Dimokratiki Aristera ) until June 2013 ; from then on from ND and PASOK.

In December 2014, the Samaras government failed to get a new president elected in parliament : the candidate did not receive the required majority in any of three ballots (details here ). After the failure of the third ballot (December 29th), the President had to dissolve parliament within ten days and call a parliamentary election . The election took place on January 25, 2015.

General election 2015 and further developments

| Financiers | accept | Paid |

|---|---|---|

| ESM | 86.0 | 55.2 |

| total | 86.0 | 55.2 |

| Source: BMF / EFSF | ||

The early parliamentary election of 2015 was won by the left-wing SYRIZA under party leader Alexis Tsipras with a surprisingly high share of the vote of 36.34% (2012: 27.77%). After Tsipras and Panos Kammenos had been able to agree on a coalition government between SYRIZA and ANEL ( Cabinet Tsipras I ), he was sworn in as Greek Prime Minister the day after the election.

On August 20, 2015, Tsipras announced his resignation, so that another election took place in Greece on September 20, 2015. Syriza received 35.46% of the vote, the conservative Nea Dimokratia 28.10%, the right-wing radical Chrysi Avgi (Golden Dawn) 6.99%, the Dimokratiki Symbarataxi (electoral alliance of PASOK and DIMAR) 6.28% and the right-wing populist ANEL ( Independent Greeks) 3.69%. Tsipras continued the coalition with the ANEL ( Tsipras II cabinet ).

On December 9, 2016, Prime Minister Tsipras announced that he would pay out a one-off total of 617 million euros to around 1.6 million Greek pensioners with a monthly pension of less than 850 euros. On December 15, 2016, the Greek Parliament approved this plan. Other governments of euro countries criticize the fact that the measure was not discussed with them. The ESM euro rescue package then stopped the debt relief that had been agreed shortly before.

causes

External causes

The EEC internal market

After the Greek people freed themselves from a 7-year military dictatorship tolerated by Washington in 1974 , political pressure from their NATO partners was feverishly working on its integration into the EEC . Germany in particular got involved in this and established its political relations with the newly founded parties PASOK and ND in 1974 so that they could develop the necessary political will-formation among the population to accept future membership of the EEC; but in vain. At that time, well over 50% of the workforce on the Greek labor market were self-employed or entrepreneurs. But it was precisely these who feared having to compete within the EEC on their traditional markets with dumping prices from Western European corporations, which would significantly restrict free competition through monopoly. That is why the political election campaign against the ruling conservative ND was extremely controversial. The left opposition even issued the slogan: “Get out of NATO!” And “not into the EEC”.

Despite this criticism, the country joined the EC in 1981. As a result, Greece elected 59% of the left parties in the 1981 parliamentary elections , namely the young Panhellenic Socialist Movement (PASOK) and the traditional Communist Party of Greece (KKE, founded in 1918). PASOK achieved a majority of 48.1% with its EC-critical election program, while the KKE, after decades of persecution, achieved a respectable 10.9% (third place) and entered parliament despite being disadvantaged by the new electoral law. After two legislative periods and shortly before the introduction of the internal market, the political mood in the country was once again whipped up. A total of three parliamentary elections and changes in the electoral law were necessary within ten months in order to form a "stable" conservative government under Konstantinos Mitsotakis in April 1990 with a majority of only one vote. In the following July the free movement of capital came into force in the EEC with far-reaching economic consequences (Directive 88/361 / EEC), and in February 1992 Greece also signed the Maastricht Treaty . After just one year, Mitsotakis was again replaced by Papandreou.

The creation of the European internal market was accompanied in the 1990s by the Greek governments with the first reform measures that were in line with the EC, ostensibly to improve the competitiveness of the Greek economy. In fact, however, the national market should be freed from the countless small businesses and thus made more attractive for new investors. At that time the self-employment rate fell very rapidly and has since been around 35% of employees (OECD); despite everything still the highest in Europe. The freed workers were not absorbed by the newly emerging large companies. In fact, in the 90s, additional investment funds flowed into the EC industrialized countries, where capacities were significantly expanded and the markets of the EC southward expansion were flooded with mass-produced goods at dumping prices. The Greek private sector largely withdrew from mechanical engineering and processing, focusing on mineral resources, agriculture and summer tourism. In order not to jeopardize the process of restructuring due to the resulting hardship, the EC supported the country with grants from the Cohesion and Structural Funds, with which, for example, the infrastructure was to be improved. As a result, competitiveness (except for mineral resources) plummeted in just a few years. Consumers in the industrialized EU countries still prefer cheap agricultural products today, some of which are produced in greenhouses with the industrial use of pesticides and fertilizers. In summer tourism, the closer countries Spain, France and Italy are traditionally preferred (although there is currently an increase in Greece). As a result, after joining the EEC, the trade balance was permanently destabilized. At that time the Greek central bank tried to give foreign trade additional impetus by steadily devaluing the drachma, but the benefits were only temporary and the drachma fell significantly in value. In addition, traditional exporting countries have now lost their competitiveness on the Greek markets due to the devaluation. This could only be prevented by a common currency.

Transnational Corruption

Since the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act 1977 came into force in the USA, the problem of legal corruption in international trade has moved into the focus of political attention. The idea that in order to fight international corruption it is necessary to prosecute not only those who are passive but at least the same amount of those who are actively corrupt, had prevailed within the OECD . Even then it was recognized that close ties between politics and business were traditionally cultivated, especially in industrialized countries. These relationships were regulated by law and seldom open to legal challenge.

With the expansion of the EEC to the south and in preparation for the later internal market in the 1980s, in the competition between exporting countries, these relationships were expanded to the new markets by means of enormous capital pressure, so that local client networks were gradually displaced from there. Bribes to officials of the southern expansion were still denounced as corruption in the target country, but could no longer be legally prosecuted because in the exporting countries bribes abroad were expressly allowed and in some countries even state co-financed through tax exemptions . Despite deductibility, the mandatory naming of the recipient has now been abolished in the local tax return in order to thwart his prosecution in the context of administrative assistance proceedings in his home country. In addition, a parliamentary motion by the SPD opposition to abolish the tax deductibility of bribes and kickbacks (Bonn, 1993) before the Maastricht Treaty came into force (printed matter 12/4104, German Bundestag - 12th electoral period):

- Reason

- When calculating the taxable profit, bribes or kickbacks are deductible as business expenses if they are paid for operational reasons. For tax deductibility, it is irrelevant whether the payments are prohibited by law or immoral (Section 40 of the Tax Code). The only requirement for the deduction is that the recipient is named at the request of the tax authorities (Section 160 (1) of the Tax Code).

- When paying bribes and bribes to foreign recipients, proof of receipt is even waived if it is certain that the recipient is not subject to German tax liability. By taking bribes to foreign recipients into account, the Federal Republic of Germany encourages active bribery abroad. This contradicts statements made by the German government, according to which great importance is attached to the element of legal security and the fight against corruption in developing countries. It is therefore imperative for the credibility of German politics abroad to lift this contradiction and to abolish the tax deductibility of bribes and kickbacks.

The economic impact of low-GDP countries with traditionally small state administrations and jurisdictions such as Greece has been the subject of controversy. In most cases, however, the practice of bribery was further developed against morality and for economic profit. It was not until 1999 that a “ Convention on Combating Bribery of Foreign Public Officials in International Business Transactions ” came into force under pressure from the OECD , so that cases of transnational corruption have been legally prosecutable since the beginning of the millennium .

Internal Greek causes

The causes of the financial crisis in Greece are controversially discussed and assessed. The following assessments of possible causes were given in various publications:

Failure to meet the convergence criteria

Greece was one of those states which did not meet the EU convergence criteria “in decision year” 1999 with a government deficit of 3.07% of GDP and a debt ratio of around 100%; as participation was possible when the reference value was approached and the trend was “sufficiently negative”, it was accepted into the euro zone in 2001. In fact, only Sweden and Estonia have met the EU convergence criteria at all times since the introduction of the euro.

Contrary to the Maastricht Treaty , according to which a euro country must reduce both the annual budget deficit and the national debt towards the limit even after the introduction of the euro, Greece was unable to reduce the criteria that were exceeded. The interest burden ratio (government interest expense in relation to GDP) fell, but was still higher than that of other euro countries and rose again.

Methodological deficits in official statistics

The development of national debt and government deficits has been the subject of controversial discussion in the Greek media since the 1990s. In order not to reinforce the resentment against involuntary membership, which has prevailed since joining the EEC in 1981, the economic forecasts were presented consistently positive. When they joined the EURO in 2001, the governments of Konstantinos Simitis ( PASOK ) and Kostas Karamanlis ( ND ) began to play down the economic situation in the press and even manipulate official economic data, which were also passed on to Eurostat . In a "Report on the Statistics of Greece" from January 2010, the European Commission cites as possible reasons on the one hand "qualitative methodological deficiencies in Greek financial statistics at the level of the Statistical Office of Greece ( ESYE )" and, at the same time, a lack of (political) governance and impairment the quality of the statistics through political influence. Since July 2010, ELSTAT has been a new, non-governmental authority for statistics.

High government spending

- Above-average increase in wage costs: In the year the euro was introduced, wages in the private and public sector rose by 12 to 15 percent in 2002, compared with only 1.5 to 5 percent in the previous year. In the following years, too, wage costs rose significantly more than the EU average.

- Lack of transparency in government spending: Inadequate control mechanisms for the award of contracts for large government projects enabled corruption . In particular, the topic of active German corruption in Greece was raised in the German and Greek media. On the occasion of a press conference by Finance Ministers Varoufakis and Schäuble, the journalist Παντελής Βαλασόπουλος insinuated that the German private sector was involved in 90% of corruption cases in Greece in his question, which was much noticed in the two countries.

- German armaments companies had fed Athens officials to systematically increase military spending in Greece since joining the EEC. But also areas of medical care have been manipulated by German pharmaceutical companies with bribery payments to optimize profits. Siemens alone "invested" € 100 million in bribes in the Greek administration. The newspaper Το Βήμα reported in July 2010 that a public administration inspection examined a selection of 164 out of around 500 sales contracts for hospital equipment. In all of them, Siemens was the sole applicant to conclude the contract. In addition, purchase and service prices were not negotiated. Above all, the far overpriced service has been earned for years.

- Size and efficiency of the state apparatus : Traditionally, in Greece, too, the rulers in each case provide the members of their party with jobs in the public service, which means that there is a risk that the state apparatus will be inflated and not filled according to competence. In the case of Greece, however, this could not be confirmed from statistical economic data from the OECD, on the contrary:

- In the two OECD publications Government at a Glance 2013 and Government at a Glance 2015 , the authors compare public sector employment with the total labor force of all member states. According to this, the share of employees in the public sector (public administration + public companies) for Greece was 19.7% in 2001, increased to 20.7% in 2008 and decreased to 17.5% in 2013. The OECD average was around 19% in 2009 and 2013. The corresponding figures in the euro crisis country Ireland were 17.9% (2001), 18.3% (2010) and 17.5% (2013), in Spain 14.1% (2001), 13.8% ( 2011) and 12.7% (2013).

- A census of all public employees carried out in July 2010 resulted in the number 768,000 with a workforce of 4.945 million (15.5%) (for the figures see also the section on the effects of the austerity measures ). In 2011, non-official, economically liberal sources in the German press spoke of around 1.1 million state employees. However, this non-standardized number comes from a list of different dates by the Athens Chamber of Commerce and Industry. For example, all 177,600 members of the military were incorrectly counted, including conscripts. According to the authors' estimate, 550,000 of these government employees are employed on a temporary basis. The Γενικό Λογιστήριο του Κράτους (in German about: General State Audit Office ) estimated that in 2012 the number of public employees had fallen to 727,458 (4.828 million people in the labor force) (15.1%). Because of the dramatic rise in unemployment over the same period, the share of public employees in the total number of employed had increased from 17.5% (2010) to 19.3% (2012), although the absolute number of public employees actually fell by over 40,000 . More information can be found in the Public Administration Reform section .

According to the diagram, Norway and Denmark have the largest state administrations, while Greece has the smallest.

- Size and efficiency of the state administration : In contrast to most EU countries, Greece employs the majority of its public employees in public companies (e.g. water, electricity, transport, telecommunications). In 2008 that was 12.8% of the labor force (with a total of 20.7% in the public sector). The public enterprises secure a substantial part of the state revenue. However, they represent an obstacle for private investors in these markets. By way of comparison: in Spain almost all public employees (13.8% see above) are employed in the state administration, not in public companies. In contrast, OECD statistics show that Greece has had the smallest general government of all 16 EU countries included in the statistics for at least a decade and a half . The OECD explains: "With less than 8% of the labor force employed by the government, Greece has one of the smallest government workforces among OECD countries."

- Afterwards Greece employed z. In 2008, for example, 7.9% of the labor force in the state administration and thus the lowest proportion of all EU countries shown in the source. Traditionally, more than half of them are employed on a temporary basis. In contrast, as in almost all European countries, Greece does not have a so-called official status , as the German press repeatedly claims. In fact, all government employees (δημόσιοι υπάλληλοι = public employees) are subject to tax and insurance and, in contrast to "civil servants", have the right to strike and the right to terminate the contract. Few of them are permanently employed. The division of annual income into 14 monthly salaries, which is much criticized in the German media, is not a financial advantage for state employees; the division of the 12 monthly salaries into 14 corresponds to a free loan for the state. More information can be found in the Public Administration Reform section .

- Phantom pensioners: A frequently cited example of the inefficiency of the Greek administration is the unusually frequent fraudulent use of social benefits up to long-undiscovered old-age pension payments beyond the death of the recipient (“phantom pensioners”).

- In the autumn of 2010, the authorities began to look for them more intensely and ordered that all pensioners should report to the authorities, including those who lived in remote areas or abroad. Shortly before the deadline in November 2011, around 21,000 retirees had not reported who were exaggerated in the press as deceased or "phantom retirees".

- In fact, that figure was way over the top, but it served as an excuse for the government to temporarily suspend pension payments to 63,500 recipients. This enabled the pension funds to withhold 450 million euros annually for the time being. In early 2013, after a 2-year study, Labor Minister Giannis Vroutsis presented the actual figures to parliament. According to this, his authority uncovered a total of 41,576 cases of unjustifiably paid payments from all social security funds combined, but only 1020 cases of deceased pensioners. Vroutsis put the total damage to the social security funds at € 420 million per year.

- High military spending: There have been tensions between Greece and Turkey since the 1970s; during this time both countries have rearmed themselves; this is considered an arms race . At times, Athens spent almost six percent of its gross domestic product (GDP) on the military, more than any other NATO country except the United States. Armaments were bought in particular from the USA, Germany and France. During the crisis, Greece ordered two additional submarines in Germany. The troop strength of 128,000 soldiers was reduced to 106,000 during the crisis.

More information can be found in the section on reducing military spending .

The measures taken by the Greek government to reduce government spending and their effects are described in the section Measures taken by the Greek government .

Low government revenue

The low level of government revenue in Greece is based on low tax revenue. Different, also controversial reasons are given by different sources. Frequently mentioned reasons are listed below.

- Low income taxes: This is due to one of the lowest employment rates in a comparison of all EU countries. According to EUROSTAT, only around a third of the population in Greece has been in employment for years. A third of them are self-employed. That means only one in five has a job at all.

- Low income and wealth taxes: Greece had cut some taxes in the years before the crisis, which resulted in a reduction in government revenues. In 2007 taxes on income from profits and assets were 15.9% in Greece and 24.4% in Germany; the highest in the EU is in the UK at 42.7%.

- Non-recoverable tax debts: In October 2009, Greek citizens and companies owed the state around 31 billion euros. To increase government revenue, the government increased taxes and levies and introduced various new taxes. The tax investigation was intensified, some defaulting payers were arrested and the biggest tax evaders were published on the Internet in July 2012. Despite or precisely because of these measures within the recession, government revenues fell to a minimum of 84 billion euros by 2014 (EUROSTAT). In July 2016, a list of the biggest tax evaders was published for the second time since January 2012. The listed 13,730 natural and legal persons owed the Greek state a total of around 83 billion euros. The list also includes companies and individuals who are already insolvent, so that a full repayment of the tax debt cannot be assumed. More information can be found in the section on combating corruption and the shadow economy .

- Above-average shadow economy: In Greece, the national shadow economy is traditionally denounced as being above-average in relation to the small population. But in fact this is true as for all Niedrich-GDP countries only for the shadow Economic quote . This is the quotient of the (absolute) shadow economy and the national gross domestic product (GDP). It thus corresponds to the average per capita shadow economy in units of per capita GDP. According to the study "The Shadow Economy in Europe 2013" by the University of Linz, it was 24.3% of GDP in Greece in 2008, the estimates for 2013 and 2015 were 23.6% and 22.0% (corresponding figures for Germany: 14.2%, 13.0% and 10.4%). Due to the high shadow economy - in 2013 it amounted to 43 billion euros - Greece loses tax revenues in the double-digit billions every year. On the other hand, according to the study, the absolute Greek shadow economy per capita lies at € 3,900 / capita in the EU average (for comparison: Germany € 4,300 / capita, Sweden € 6,100 / capita, top runner Luxembourg € 6,800 / capita, see diagram on the right). The following figures were estimated for 2015: Greece € 3,600 / person, for Germany € 3,900 / person shadow economy. More information can be found in the section on combating corruption and the shadow economy .

- Smuggling: It is estimated that the Greek treasury has lost around 25 billion euros in the past 20 years through gasoline smuggling and gasoline fraud. The problems with cigarette smuggling are similar.

The measures taken by the Greek government to increase government revenue and their effects are described in the section Measures taken by the Greek government .

Insufficient enforcement of the EU treaties

Some authors cited the inadequate enforcement of the EU treaties as one of the causes. The ban on assuming liability for debts ( non-bailiff clause ) set out in the Maastricht Treaty has also been undermined.

“1. The Union shall not be liable for the liabilities of central governments, regional or local authorities or any other public law corporation, other public law body or public company of Member States, and shall not assume any liability for such liabilities; this is without prejudice to the mutual financial guarantees for the joint implementation of a particular project. A Member State shall not be liable for and assume no liability for the obligations of central governments, regional or local authorities or other public bodies, other bodies governed by public law or public undertakings of any other Member State; this applies without prejudice to the mutual financial guarantees for the joint implementation of a particular project. "

Despite early knowledge of the economically critical situation of countries like Greece, the EU authorities have neither effectively addressed the failure of the criteria nor promoted countermeasures. According to the journalist Ursula Welter , the lack of automatic sanctions in the case of increasing debts is objectionable. In the short term, EU countries are allowed to expand their budget balances and debt levels excessively without fear of consequences from the EU.

Abusive Lending

In connection with the Greek sovereign debt crisis, banks are accused of improper lending because, similar to before the subprime crisis , they granted loans although they had already recognized Greece's financial distress. The economic historian Werner Abelshauser reports that he was laughed at at a conference in 2010 when he mentioned the no-bailout clause ; apparently the investors and bankers present did not consider this clause credible. According to other sources, the lenders misjudged the risk. It was not until the outbreak of the financial crisis in 2007 that risk premiums on Greek government debt began to rise.

Low investment

With the exception of 2003, investments have declined since the introduction of the euro, which was criticized because of the high level of investment required.

Mutually reinforcing causes

Both the increasing national debt (repayment burdens) and the rising risk premiums (interest on government bonds) weighed on the Greek budget. After the bank bailout, any deterioration in the economic outlook led to a sharp rise in risk premiums for government bonds. The resulting increase in debt, in turn, increased interest rates, so that causes reinforced each other and led to ever higher costs of capital.

Crisis Management Measures

Actions by the EU, the ECB and the IMF

After Greece officially applied for EU aid in April 2010, the European Union (EU), the European Central Bank (ECB) and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) agreed with the Greek government on May 2, 2010, to launch a first aid package Loan Facility Agreement ). This first rescue package included aid in the form of loans and guarantees. The second package was decided in February / March 2012 and, in addition to loans and guarantees from the European rescue fund EFSF , included a reduction in lending rates and debt rescheduling (partial debt relief). Private creditors also participated in the rescheduling; However, their contribution of 40.9 billion euros was 100% offset from the 2nd aid package.

| time | Amount of committed cash transfers | Amount of money transfers made | Financiers | Amortization-free period and due date | interest rate | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First aid package | April 2010 | 107.3 billion euros | 73.0 billion euros | Eurogroup 52.9 billion euros IMF 20.1 billion euros |

Eurogroup: 10 and 30 years IMF: repaid in 2016 |

Eurogroup: 50 basis points above the 3-month Euribor IMF: approx. 3.96% |

| Second aid package |

February / March 2012 | 130.1 (+ 34.3) billion euros | 142.7 billion euros | EFSF 130.9 billion euros, IMF 11.8 billion euros |

EFSF: maturity 32.5 years on average IMF: maturity 2026 |

EFSF: no guarantee fee, deferral of some interest payments for 10 years IMF: approx. 2.85 to 3.78% |

| Third aid package |

August 2015 | 86 billion euros | 61.9 billion euros | ESM 61.9 billion euros | ESM: Maturity 32.5 years on average |

ESM: approx. 0.86% |

| Σ | until Aug. 2018 | 323.4 billion euros | 277.6 billion euros | Eurogroup / EFSF / ESM € 245.7 billion, IMF € 31.9 billion |

- | - |

| Loans | EURO rescue | total | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (nat.) | IMF | € zone | Non-€ countries | EFSF | EFSM | ESM | ||

| Greece | 66.5 | 31.9 | 52.9 | 130.9 | 61.9 | 344.1 | ||

| Ireland | 17.5 | 22.5 | 4.8 | 17.7 | 22.5 | 85.0 | ||

| Portugal | 26.6 | 26.0 | 24.3 | 76.9 | ||||

| Spain | 41.3 | 41.3 | ||||||

| Cyprus | 1.0 | 6.3 | 7.3 | |||||

| total | € 166 billion | € 388.6 billion | € 554.6 billion | |||||

Globalization critics accused those responsible for the design and implementation of the aid packages of "having used hundreds of billions of public money to save banks and other financial actors and, above all, their owners from the consequences of the financial crisis they caused". Instead of helping the Greek people, the measures would rather benefit financial institutions and speculators. A research carried out by Attac Austria in 2013 revealed that “at least 77.12% of the program funds had flowed directly (via bank recapitalization) or indirectly (via government bonds) to the financial sector” from the rescue program for Greece.

As of September 30, 2016, Greece's debt was € 311.16 billion. At this point in time, the main donors with a 68.4% share were other euro countries (the share is made up of bilateral loans, EFSF and ESM), other donors (22.5%), the IMF (4.2%), the ECB (4, 0%) and the Bank of Greece (1.1%). From 2010 to 2015, Greece paid 52.3 billion euros in interest to creditors, and around 70 billion euros is expected by 2018. In a debt sustainability analysis from February 2017, the IMF suggests another extension of the grace period until 2040, an extension of the maturity of Eurogroup, EFSF and ESM loans until 2070, a waiver of interest payments until at least 2040 and interest rates of a maximum of 1.5% for stipulate a term of 30 years for EFSF and ESM loans. This rescheduling (ultimately a renewed debt relief) should help Greece to stimulate the economy on its own and to be able to repay its (then reduced) debts at a later point in time. The proposals are based on an IMF development forecast. The forecast deviates significantly from the forecast of the European Commission from March 2017.

The agreements on the first and second aid package have been supplemented and changed several times. The following table shows the changes:

| designation | time | Name of the change | Changes |

|---|---|---|---|

| First aid package | May 2010 | Euro Area Loan Facility Act 2010 (Initial Agreement) |

|

| June 2011 (decided in March 2011) |

Euro Area Loan Facility (Amendment) Act 2011 (Adapted Agreement) |

|

|

| February / March 2012 | Euro Area Loan Facility (Amendment) Act 2012 (Adapted Agreement) |

|

|

| February 2013 (decided in December 2012) |

Euro Area Loan Facility (Amendment) Act 2013 (Adjusted agreement) |

|

|

| Second aid package | November 2012 |

(Adapted Agreement) |

|

| Third aid package | August 2015 |

(Original agreement) |

|

Legal basis of EU and IMF aid

The non-assistance clause of the European Economic and Monetary Union (EMU), Art. 125 TFEU , according to an analysis by the service of the German Bundestag (2010), excludes automatic liability ( obligation to provide assistance) of the European Union and the member states for liabilities of other member states. According to the interpretation, however, it does not emerge from the non-assistance clause how the voluntary assumption of debts by other states ( rescue operation ) is regulated. Because of this article, there was a complaint as to whether the loans granted (including to Greece) by the member states or the EFSF / ESM were lawful. The European Court of Justice (ECJ) ruled that these measures are compliant with European law.

The International Monetary Fund IMF , based in Washington, has the task of stabilizing the international financial markets.

First Greece program, rescue package from EU and IMF - May 2010

At the beginning of 2010, the assessment of the financial situation of Greece by the capital market players deteriorated so much that insolvency threatened. It was feared that banks that had lent money to Greece would also get into serious difficulties with further effects on the euro currency system.

On April 11, 2010, the members of the Eurozone decided to grant aid loans to Greece. After rating agencies further downgraded Greece's creditworthiness and the risk premiums for long-term Greek government bonds reached record levels, the Greek government officially applied for financial assistance on April 23, 2010.

The European Union (EU), the European Central Bank (ECB) and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) reached an agreement on January 1st and 2nd. May 2010 with the Greek government on a three-year financial aid program in the form of bilateral loan guarantees totaling 110 billion euros. The donors did not assume any liability for Greece's outstanding debts.

In return, the Greek government under Prime Minister Giorgos A. Papandreou ( PASOK ) undertook to implement radical reforms. The Greek budget should be consolidated within three years to such an extent that the budget deficit would have fallen below 3% by 2014. This first aid program is known by different names: These include “First Rescue Package”, “Greek Loan Facility” and “First Economic Adjustment Program for Greece”.

Of the 110 billion euros initially committed, the IMF initially took on 30 billion euros and the euro zone 80 billion euros as bilateral loan commitments. Decisive for the determination of the quotas of the individual euro states on the 80 billion euro zone was the respective capital share in the capital of the ECB , which in turn is determined every five years according to the respective share of a country in the total population and economic output of the EU. The € 80 billion amount was reduced by € 2.7 billion to € 77.3 billion after Slovakia decided not to participate in the Loan Facility for Greece (GLF). Ireland and Portugal also did not participate, as they applied for or received grants themselves. In total, the loan assistance committed in May 2010 amounted to 107.3 billion euros. In 2010, the guarantee for Germany amounted to 8.4 billion euros, and another 14 billion euros should follow in the following two years. On May 7, 2010, the German Bundestag and the German Bundesrat approved aid to Greece and passed the Monetary Union Financial Stability Act .

The disbursement of the loans to Greece was planned between May 2010 and June 2013. The transfer of the quarterly tranches was linked to compliance with the measures agreed in the restructuring package. This had to be confirmed by joint reports by the so-called Troika , i.e. the European Central Bank , the International Monetary Fund and the European Commission .

| Period |

Eurogroup (Lending Facility for Greece, GLF) |

IMF | All in all | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18./12. May 2010 | 14.5 billion euros | 5.5 billion euros | 20.0 billion euros | 1st tranche of the first aid package (transferred) |

| 13./14. September 2010 | 6.5 billion euros | 2.5 billion euros | 9.0 billion euros | 2nd tranche (transferred) |

| January 19, 2011 / December 21, 2010 |

6.5 billion euros | 2.5 billion euros | 9.0 billion euros | 3rd tranche (transferred) |

| March 16, 2011 | 10.9 billion euros | 4.1 billion euros | 15.0 billion euros | 4th tranche (transferred) |

| 15./13. July 2011 | 8.7 billion euros | 3.3 billion euros | 12.0 billion euros | 5th tranche (transferred) |

| 14./7. December 2011 | 5.8 billion euros | 2.2 billion euros | 8.0 billion euros | 6th installment (transferred) |

| total | 52.9 billion euros | 20.1 billion euros | 73.0 billion euros |

The 73.0 billion of the originally promised 107.3 billion euros were ultimately paid out to Greece from May 2010 to December 2011. The remaining, around 34.3 billion euros, “are to be paid out via the EFSF, which also includes the Funding of the second aid package to Greece will be ongoing ”.

See also the section on Financial Consequences for Creditors .

Second bailout package from EU and IMF - July 2011 to February / March 2012

After the first rescue package had proven to be inadequate, a “second” rescue package for Greece was decided at an EU summit of the 17 euro countries on July 21, 2011. The aid package had a total volume of 109 billion euros and can be disbursed by the newly created EFSF , an institution of the participating states, and the International Monetary Fund until 2014 and loaned at the low interest rate of 3.5%. For the repayment of all the funds made available by the rescue fund, Greece was granted a term extension from seven and a half to 15 years.

For the first time, participation by the private financial sector on a voluntary basis was agreed ( voluntary so-called debt haircut (debt relief) ). The net contribution from banks to support Greece should be € 37 billion by 2014. However, Greece had undertaken to reimburse the banks for this default 100% from the aid loans of the second package. Furthermore, a reconstruction plan for Greece was announced at the EU summit in order to promote economic growth. The EU Commission set up a "Task Force for Greece".

The German Bundestag approved an expansion of 29 September 2011 EFSF to.

In view of the uncertainty surrounding domestic political developments in Greece, the agreed payment was initially suspended after Prime Minister Papandreou announced a referendum on the decisions of the euro summit on November 1, 2011 ; Papandreou dropped this plan after two days, but then had to announce the formation of a new government in order to survive a vote of confidence . He was succeeded as Prime Minister on November 11, 2011 by Loukas Papadimos ; he formed a transitional government .

IMF report December 2011

On December 14th, the 'IMF Country Report No. 11/351 'known. In the extensive report, the IMF ruled out additional financial aid for the near future.

“After talks between the Troika and the Greek government, the head of the IMF mission to Greece, Poul Thomsen, said the IMF representatives had not traveled to Athens to discuss a 'new program'. There is a commitment of support from May 2010 for 30 billion euros. More is currently not to be expected. "

The IMF criticized the same as the OECD last week. The OECD had examined all 14 ministries and came to the conclusion in a study that there was neither a vision of the reform goal nor a control for implementation, hardly any communication within the authorities and a complicated administrative network without any coordination. The only way out is a “big bang reform” in the entire government apparatus - that is, radical cuts.

Ratification of the "second" aid package in February and March 2012

The finance ministers of the euro zone agreed in February 2012 on a “second” aid package for Greece, including loan commitments of 130 billion euros (originally 109 billion euros). In return, Greece had to accept more controls and surrender part of its budget sovereignty. The conditions also included setting up a blocked account. The interest rate for the loans from the first aid package was retrospectively reduced to 150 basis points above the Euribor for the entire term . The German Bundestag approved the aid package on February 27, 2012.

The agreement on the second aid package has been amended and amended several times. In November 2012, the measures included:

- Retrospective reduction in lending rates by 100 Euribor basis points from the first aid package

- Reduction of the fees for guarantees on the EFSF loans by 10 basis points (equivalent to 0.1%)

- Loan maturity of both aid packages increased by 15 years

- Deferred interest on EFSF loans for 10 years

- Transfer of the income from the 2013 financial year of a respective national central bank from the Securities Markets Program to the blocked account of Greece

Haircut and official default in March 2012

On the night of October 26-27, 2011, the euro countries drafted - after a preparatory meeting a few days earlier and after a vote in the Bundestag on October 26, 2011 - a plan through which Greece in the long term - until 2020 - again without financial aid Abroad should get along. The basic aim was to reduce the country's debt level from 160% at the time to 120% of gross domestic product (GDP). The positions of the EU Commission from October are given in the 'Occasional Paper 87/2011'. Lenders should exchange their government bonds for new bonds in January. The member states belonging to the euro area should contribute up to 30 billion euros to the participation of the private sector (English private sector involvement - PSI). The “clout of the EFSF” should be increased to one trillion euros through a “ lever ”.

At the beginning of March 2012, the Greek government announced that it had reached an agreement with 85.5% of private creditors on voluntary debt relief of 100 billion euros, although the target figure of 90% was just missed. Since this did not take place with the consent of all bondholders, the ISDA determined on March 9, 2012 that Greece was in default. Reluctant investors should be forced to give up. The haircut is ultimately 107 billion euros in the period from 2011 to 2019. [outdated]

Criticism was raised, among other things, because of the late debt haircut adopted by the EU summit, which was previously excluded from politics. The beneficiaries of a later haircut compared to an earlier haircut (around 2009) are private banks that were able to sell their Greek government bonds, some of which were bought by the ECB . However, the ECB itself did not participate in the PSI, which increased the loss of privately held debt to achieve the fixed target of debt reduction. At the time of the haircut in 2012, private creditors still held around a third of Greek government debt. Due to the loss of private creditors associated with the haircut, the proportion of state creditors rose, especially since Greece was recapitalized Greek banks.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) granted loan assistance of 28 billion euros on March 15, 2012 (PM No. 12/85).

| Period | EFSF | IMF | All in all | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| March 12 to June 28, 2012 | 74.0 billion euros | 1.6 billion euros | 75.6 billion euros | The first payment under the second program was made in seven tranches. |

| December 2012 to May 2013 | 49.1 billion euros | 3.24 billion euros | 52.34 billion euros | The second payment was made in four tranches |

| May to June 2013 | 7.5 billion euros | 1.74 billion euros | 9.24 billion euros | The third payment was made in two tranches |

| July to December 2013 | 3.0 billion euros | 1.8 billion euros | 4.8 billion euros | The fourth payment was made in two tranches |

| April to August 2014 | 8.3 billion euros | 3.6 billion euros | 11.9 billion euros | The fifth payment was made in three tranches |

| Σ | 141.9 billion euros | 11.98 billion euros | 153.88 billion euros |

The financial needs and the related financial aid payments were estimated at a total of 163.9 billion euros between 2012 and 2014. Of this, the EU would contribute EUR 144.7 billion and the IMF EUR 19.1 billion.

After the transfer of the last tranche of the fifth payment in August 2014, the fifth review was due, which, if the findings were sufficient, should be followed by the sixth payment by February 28, 2015, the scheduled end of the program. The review dragged on until early elections became apparent in December 2014 and the review process was suspended. On February 27, 2015, an agreement was reached with the newly elected Syriza government to extend the aid program by four months, during which the previous reform plan should be revised and the fifth review should then be completed.

Actions by the European Central Bank

In May 2010, the European Central Bank bought Greek government bonds worth 25 billion euros. The ECB announced that it would accept Greek bonds as collateral regardless of their rating status. In 2011, she continued to buy Greek government bonds.

As part of its " Securities Markets Program " (SMP), the ECB bought between May 2010 and around February 2012 bonds worth 220 billion euros from euro countries that were no longer able to easily refinance their debts on the capital market, including Greek bonds with a nominal value of an estimated 50 billion euros. For this she was massively criticized in Germany. Finally, the Greek central bank can as part of the central banks of the European System of liquidity help in an emergency ( Emergency Liquidity Assistance grant).

Measures by the Greek government

The measures listed below have been agreed between Greece and its creditors.

First savings package - March / April 2010

On March 3, 2010, VAT was increased from 19% to 21% with effect from March 15, 2010 and a decision was made to reduce civil servants' salaries. This should save 4.8 billion euros annually. In addition, the Christmas and vacation pay for all civil servants was cut by 20% and all allowances by 30%.

On April 28, 2010, the cabinet decided on an administrative reform with the Kallikratis Plan . A new decentralized orientation of the administration as well as the implicit reorganization of responsibilities should save administrative expenses of 1.8 billion euros annually. Among other things, it was planned to permanently cut the 13th and 14th monthly salary of civil servants.

Second savings package - May 2010

On May 2, 2010, the Greek government decided on a package of measures negotiated with the IMF and the EU. The following measures should save around 30 billion euros by 2013:

- Freezing of civil servants' salaries over 2000 euros

- Reduction of the administrative levels from five to three

- Reduction of city administrations from currently over 1000 to 370

- Deletion of the 13th and 14th monthly salary or monthly payments in the public sector

- Freeze on hiring in the public sector: only every fifth position that becomes vacant in the public sector is to be filled. In autumn 2011, further positions are to be deleted.

- Increase in the average retirement age from 61.3 to 63.4 years

- Increase in VAT from 21% to 23% and increase in taxes on tobacco, spirits and fuel

- Deletion of 13th and 14th monthly payments for pensioners

The Greek parliament passed the austerity package on May 6, 2010.

Third savings package - June 2011

The Greek parliament approved the government's third package of cuts on June 29, 2011. 155 of the total of 300 MPs voted in favor in the roll-call vote, 138 voted against, 5 abstained and 2 did not take part in the vote. By 2015, the Papandreou government wanted to save around 78 billion euros (around 28 billion euros through benefit cuts and tax increases, 50 billion through privatizations and the sale of state property). The adoption of the austerity package was the decisive prerequisite for the release of a further, fifth, tranche from the 110 billion euro first rescue package by the EU and IMF.

Main points of the third package:

- Taxes: The wealth tax will be increased as will the value added tax for various areas. In addition, a “solidarity tax” will be introduced and tax exemptions will be eliminated.

- Wages: By 2015, the number of employees in the public sector is to be reduced by 150,000, the remaining civil servants have to work longer.

- Social benefits: The assets of benefit recipients are to be reviewed and a number of benefits cut.

- Defense: In the coming year the country wants to save 200 million euros on armaments, from 2013 to 2015 it should then be 333 million euros annually.

- Health system: In 2011, 310 million euros and a further 1.43 billion euros are to be cut by 2015 - for example by lowering the state-set prices for drugs.

- Investments: This year, 700 million euros less should flow, half of this sum should disappear in the long run.

- Privatizations: Many state-owned companies are to switch to private hands. For this purpose, on July 1, 2011, a privatization company named Hellenic Republic Asset Development Fund (HRADF) was set up. It is uncertain whether appropriate prices can be obtained for companies in the current situation.

At the beginning of 2012 it became known that privatization was hardly making any significant progress and that the revenues of 11 billion euros promised by Greece for 2012 seem unrealistic.

Announcement of another savings package - September 2011

On September 21, 2011 the Greek government announced new austerity measures. The tax exemption should be reduced from 8,000 euros to 5,000 euros. Furthermore, 30,000 positions in the public service should be cut. Civil servants and other civil servants should be sent to what is known as a “work reserve”. They should receive 60% of their income for a maximum of twelve months before an independent authority should make a decision on whether to continue to work or to dismiss.

The project was withdrawn and there was a change of government.

Papandreou government resigned - November 2011

The then Prime Minister Papandreou announced on November 1, 2011 a referendum on the decisions of the Euro Summit in Brussels on aid to Greece, which were linked to further drastic austerity requirements, but dropped this plan on November 3, after the upcoming loan disbursement of eight billion euros (“Rescue Aid”) to Greece in view of the uncertainties surrounding domestic political developments in Greece. Papandreou put the vote of confidence in parliament on November 4th and received a majority after the announcement that he would form a transitional government with the involvement of the opposition Nea Dimokratia . A new government formed by the non-party Loukas Papadimos in November 2011, which, in addition to a large part of the previous PASOK ministers, included two ministers from the New Democracy and one from the LAOS , undertook to meet the austerity requirements. At the end of 2011, negotiations in the grand coalition were in deep crisis. Even the most urgent reforms had stalled.

The HRADF was legally legitimized by October 2011 and was therefore fully operational.

In 2011, instead of the expected 400 million euros, a total of 946 million euros in tax debts were collected. This is attributed to the establishment of a centralized structure of the tax authorities, as well as to increased tax audits.

Fourth savings package - February 2012

Another austerity package was passed in February 2012.

- Lowering of the minimum wage to 586 euros

- Reduction of the minimum wage for under 25s to 525 euros

- Reduction of the salaries of certain occupational groups in the public service retrospectively from January 1, 2012 by 20 percent

- Reduction of the unemployment benefit to 322 euros

- Reduction of pensions by 10 to 15 percent

- Increase in the co-payment for medication

- Reduction of drug costs in state clinics

- Savings in overtime for doctors

- Reduction in subsidies for cities and municipalities

- Immediate dismissal of 15,000 government employees; by 2015 150,000

- Privatization of state enterprises

- Closing 200 small, inefficient tax offices and recruiting 1,000 new tax inspectors

- Reduce military spending by 600 million euros by 2015

The treatise "The Second Economic Adjustment Program for Greece" or the HRADF provides information on the implementation status of privatization in spring 2012 . In addition to real estate and land, public utilities, road operating companies and lottery licenses are also to be sold. Numerous German companies accompany the sales process. The platform for public tenders has been active since August 28, 2013.

Fifth savings package - November 2012

In November 2012, the Greek parliament approved a renewed austerity package worth 13.5 billion euros, which provides for cuts in pensions, salaries, health and social services and the cancellation of child and Christmas benefits.

- Pensions from 1000 euros upwards are reduced by 5 to 15%

- Christmas bonus for pensioners will be abolished

- The retirement age will be raised from 65 to 67 for everyone

- Severance payments for laid-off employees will be reduced

- Elimination of Christmas and vacation pay for government employees

- Cut wages and salaries by 6 to 20% for civil servants

- By the end of 2012, 2000 state employees are expected to take early retirement

- higher personal contributions when buying medication

- Hospital reform

- Alignment of salaries of employees of public-law companies with those of state employees

- no entitlement to child benefit if the family income exceeds 18,000 euros per year

Sixth austerity package - April 2013

The government coalition in Greece agreed in April 2013 on new austerity proposals as part of their reform projects.

- Reform of Public Administration (English: public administration reform )

- the staffing plan provides for the dismissal of a large number of government employees :

- By the end of 2013, 4,000 positions (cumulatively) are to be cut in the public sector

- by the end of 2014 a total of 15,000 civil servants (cumulative) should go

- this reform project is by evaluating (English: evaluation ), a sensible redistribution of personnel through its Mobility (English: rational reallocation of personnel through mobility ), and a qualitative renewal through layoffs (English: quality renewal through exits ) are achieved. Criteria for any layoffs and specific plan values can be found on pages 130 and 231f. the essay "The Second Economic Adjustment Program for Greece - Second Review May 2013".

- the staffing plan provides for the dismissal of a large number of government employees :

- "a new property tax should be levied"

The paper “The Second Economic Adjustment Program for Greece - Third Review July 2013” provides information on the implementation status in spring 2013.

Since 2014, patients in state hospitals have had to pay 25 euros per treatment. By the end of 2014, the HRADF had sold a total of 14 pieces of land and properties, including buildings in Rome, London, Brussels and Tashkent. The building in Rome brought in € 6 million and the one in London € 22 million.

On July 18, 2015, the German Finance Minister Wolfgang Schäuble criticized in an interview that the components of the new program had already been agreed in 2010, but were inadequately implemented. In September 2016, the economic researcher Schrader, IFW Kiel, mentioned that there had been a number of privatizations, but the implementation of the desired reforms would take longer and it remains unclear whether everything will go according to the donors' wishes. In his opinion, the country needs a haircut, it is impossible that Greece can bear the debt completely. By the end of 2015, around 3 billion euros had been generated from the privatizations; there was criticism that the facilities had been sold at low prices.

Seventh and further packages from August 2016

In September 2016 the Greek government decided on further reforms.

- Non-pharmacists can open pharmacies

- In addition to bakeries, all establishments are allowed to sell bread

- Access to the engineering and notary professions will be relaxed

- Farmers lose discounts on fuel

- Shipowners will receive a higher tonnage tax until 2020

- Freelancers and traders are required to pay all of their income tax upfront

- Early retirement at the age of 50 or 55 will be abolished