Grammar of the modern Greek language

The modern Greek language emerged in a continuous development from ancient Greek and forms (together with its preliminary stages) a separate branch of the Indo-European language family .

In the area of grammar it has preserved a number of original features of this language family. In this context, the consistent distinction between aspects of the verb and the non- periphrastic formation of the passive forms should be emphasized . Recent developments affecting sentence structure are, however, the loss of the infinitive and the development of a special subordinating sentence structure, the Ypotaktiki . In terms of language typology, Modern Greek is one of the accusative languages with a predominantly synthetic / inflected language structure . The formation of the future tense by means of the preceding particle θα tha and the perfect tenses formed with the auxiliary verb έχω echo “haben”, however, show an increased tendency towards the analytical construction of language.

Categories and elements of the noun phrase

Gender and number

- Γένος & Αριθμός

As in German , the modern Greek noun distinguishes between three grammatical genders ( genera ) - male (αρσενικά), female (θηλυκά) and neuter (ουδέτερα) - as well as the two numbers singular (ενικός) and plural (πληθυντικός). The dual for the two number still present in ancient Greek is no longer present and has been replaced by the plural. The natural gender does not necessarily match the grammatical one, as in German, for example, 'the girl' ( to koritsi το κορίτσι) is neuter, in Modern Greek it is also 'the boy' ( to agori το αγόρι). The inflectional endings of a noun often do not indicate its gender, especially in spoken language. However, some subject areas allow 'rules of thumb', for example almost all island names are female.

case

- Πτώσεις

Modern Greek has four cases :

- In the nominative (ονομαστική) there is the sentence subject or a nominative attribute: I mitéra mou íne Gallída ( Η μητέρα μου είναι Γαλλίδα ' My mother is French ').

- In the accusative (αιτιατική) is the direct object of a verb: Vlépo to spíti ( Βλέπω το σπίτι , I see the house ' ).

- The genitive (γενική) can also be used as a case of the indirect object in addition to the property-indicating, attributive function : Pes tou Kósta oti den boró ( Πες του Κώστα ότι δεν μπορώ 'Say Kostas that I cannot').

- The vocative (κλητική) is only used in the direct form of address and only has its own inflection ending in masculine -os : Fíl e mou giatr é , pes mou ti gínete! ( Φίλ ε μου γιατρ έ , πες μου τι γίνεται! ' Friend doctor , tell me what's going on!'). The only masculine nouns in -os whose vocative ending is not -e are two-syllable names (Nikos, Vok. Niko) and multiple-syllable compound names, the second component of which is a two-syllable name (Karakitsos from kara + Kitsos, Vok. Karakitso).

The dative, on the other hand, has dwindled in Modern Greek, except in the case of a few established idioms (e.g. en to metaxí εν τω μεταξύ 'indes', en táxi εν τάξει 'in order'); it has its role to characterize the indirect object either on the Genitive or given to a prepositional phrase in the accusative:

| O | Giannis | mou | dini | to | vivlio |

| Ο | Γιάννης | μου | δίνει | το | βιβλίο. |

| Of the | Giannis | my | gives | the | Book. |

| Nom. | Gene. | Acc. | |||

| 'Giannis gives me the book.' | |||||

| O | Giannis | dini | to | vivlio | sto | Niko. | |

| Ο | Γιάννης | δίνει | το | βιβλίο | στο | Νίκο. | |

| Of the | Giannis | gives | the | book | in the | Nikos. | |

| Nom. | Acc. | Prep. With acc. | |||||

| 'Giannis gives the book to Nikos.' | |||||||

items

- άρθρα

Modern Greek, like German, differentiates between a definite and an indefinite article , which is based on the defining word in case, gender and number.

As an indefinite article (αόριστο άρθρο) the original numeral enas 'a', which only exists in the singular, is used. The indefinite article is generally used less often than in German, e.g. B. in connection with a predicate noun it is missing in modern Greek: O Giannis ine filos mou Ο Γιάννης είναι φίλος μου 'Hans is [a] friend of mine'.

| Masculine | Feminine | neuter | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nominative | enas (ένας) | mia (μια) | ena (ένα) |

| Genitive | enos (ενός) | mias (μιας) | enos (ενός) |

| accusative | ena (n) (ένα (ν)) | mia (μια) | ena (ένα) |

In the case of the definite article (οριστικό άρθρο) the gender distinction is also retained in the plural. It is used more often than in German, for example before personal names and proper names ( erchete o Giorgos έρχεται ο Γιώργος '[der] Georg is coming'; ime apo ti Gallia είμαι από τη Γαλλία 'I am from [the] France') . In addition, it does not disappear when using other pronouns in contrast to German ( o filos mou ο φίλος μου literally 'the friend of mine', afto to pedi αυτό το παιδί 'this [the] child').

| Singular | Plural | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Masculine | Feminine | neuter | Masculine | Feminine | neuter | |

| Nominative | o (ο) | i (η) | to (το) | i (οι) | i (οι) | ta (τα) |

| Genitive | tou (του) | tis (της) | tou (του) | ton (των) | ton (των) | ton (των) |

| accusative | to (n) (το (ν)) | ti (n) (τη (ν)) | to (το) | tous (τους) | tis (τις) | ta (τα) |

The end-n in the accusative singular is only added to the feminine and masculine articles if the following word begins with a vowel or a closing sound (/ p /, / t /, / k /…).

Nouns

- Ουσιαστικά

Modern Greek nouns and proper names differentiate the numbers singular and plural as well as the four cases nominative, genitive, accusative and vocative by inflection of ending. As in German, there are three genders (genera) masculine, feminine and neuter, although the inflected ending cannot always be used to clearly identify the gender. The definite or indefinite article almost always accompanying the noun creates clarity here.

The declension of nouns and proper names can be roughly divided into three classes:

1. The declination of the 7 forms

This declination class, taken directly from ancient Greek, has seven different forms for the eight possible combinations of number and case. Only nominative and plural vocative are marked by the same ending, as in the case of giatros γιατρός 'doctor'.

| Nominative | Genitive | accusative | vocative | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | giatr -os (γιατρός) | giatr -ou (γιατρού) | giatr -o (γιατρό) | giatr -e ! (γιατρέ!) |

| Plural | giatr -i (γιατροί) | giatr -on (γιατρών) | giatr -ous (γιατρούς) | giatr -i ! (γιατροί!) |

The vast majority of nouns in this class are masculine, only a small group is feminine, the word group around odós οδός 'street' and the names of almost all islands and many other toponyms should be emphasized.

2. The declination of the S principle

The common feature of this declension class, which only includes feminine and masculine nouns, is the presence or absence of an ending / s /.

The masculine of this type have a nominative in the singular with the ending / s / and a common form for accusative, genitive and vocative without / s /. Example andras άντρας 'man':

| Nominative | Genitive | accusative | vocative | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | andr -as (άντρ ας ) | andr -a (άντρ α ) | andr -a (άντρ α ) | andr -a ! (άντρ α !) |

| Plural | andr -es (άντρ ες ) | andr -on (αντρ ών ) | andr -es (άντρ ες ) | andr -es ! (άντρ ες !) |

The feminine of this type of declension, on the other hand, has a common / s / -less form in the singular for nominative, accusative and vocative but a genitive with / s /. Example poli πόλη 'city':

| Nominative | Genitive | accusative | vocative | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | pol -i (πόλη) | pol -is (πόλης) | pol -i (πόλη) | pol -i ! (πόλη!) |

| Plural | pol -is (πόλεις) | pol -eon (πόλεων) | pol -is (πόλεις) | pol -is ! (πόλεις!) |

A large subgroup of nouns declined according to the s-principle is formed by the plural forms with unequal syllables, i.e. a consonant is inserted as a syllable-forming element before the actual ending: giagia γιαγιά (nom. Sing.) → γιαγιά δες - i giagia des (nom. Plural) .

3. The declination of the neuter

The neuter declinations are an inhomogeneous group of declination classes, some of which have been adopted from ancient Greek and have been reduced in shape, and later developments in terms of linguistic history. What they all have in common is the correspondence between the accusative and nominative forms. Example: vouno βουνό 'mountain'.

| Nominative | Genitive | accusative | vocative | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | voun -o (βουνό) | voun -ou (βουνού) | voun -o (βουνό) | voun -o ! (βουνό!) |

| Plural | voun -a (βουνά) | voun -on (βουνών) | voun -a (βουνά) | voun -a ! (βουνά!) |

Exceptions

In addition to the regular declension groups, there are various nouns, mostly adopted from ancient Greek or constructed analogously, which cannot be clearly pressed into one of the above schemes. See Irregular Nouns in Modern Greek .

Adjectives

- Επίθετα

The adjective is based on the noun it refers to in case, gender and number. In contrast to German, this also applies when using the adjective as a predicate noun :

In the nominative ( O Giannis ine arrost os Ο Γιάννης είναι άρρωστ ος 'Hans is sick', I Maria ine arrost i Η Μαρία είναι άρρωστ η 'Maria is sick'),

or in the accusative ( Ι doulia kani tous andres arrost ous .eta δουλειά κάνει τους άντρες άρρωστ ους The working men makes you sick , Ι doulia kani tis ginekes arrost it .eta δουλειά κάνει τις γυναίκες άρρωστ ες The work makes women sick )

but also in the use as a predicate attribute (Μαρία κοιτάζει τους στρατιώτες αμίλητ .eta .eta , Γιάννης κοιτάζει τους στρατιώτες αμίλητ Ο ος Maria / Hans the soldiers considered silence ).

declination

Most of the modern Greek adjectives decline according to the following scheme or one of its variants:

| Nom. Sg. | Gene. Sg. | Acc. Sg. | Vok. Sg. | Nom. Pl. | Gene. Pl. | Acc. Pl. | Voc. Pl. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| male | kal -os (καλ ός ) | kal -ou (καλ ού ) | kalo -o (καλ ό ) | kal -e ! (καλ έ !) | kal -i (καλ οί ) | kal -on (καλ ών ) | kal -ous (καλ ούς ) | kal -i ! (καλ οί !) |

| Female | kal -i (καλ ή ) | kal -is (καλ ής ) | kal -i (καλ ή ) | kal -i ! (καλ ή ) | kal -es (καλ ές ) | kal -on (καλ ών ) | kal -es (καλ ές ) | kal -es ! (καλ ές ) |

| neutrally | kal -o (καλ ό ) | kal -ou (καλ ού ) | kalo -o (καλ ό ) | kal -o ! (καλ ό ) | kal -a (καλ ά ) | kal -on (καλ ών ) | kal -a (καλ ά ) | kal -a ! (καλ ά ) |

καλός = "good"

For adjectives ending in -os, the stem of which ends in a stressed vowel, the feminine singular forms are in / a (s) / instead of / i (s) /: i oréa (η ωρ αί α) the beautiful , but: i víeï (η β ί αιη) the violent . This is also mostly the case with learned adjectives with a stem ending in -r: i erythra thalassa (η ερυθ ρ ά θάλασσα) the Red Sea , but: i myteri lavi (η μυτε ρ ή λαβή) the pointed handle . Furthermore, some popular adjectives in the feminine singular form the forms on / ia (s) /: i xanth ia (η ξανθ ιά ) the blonde .

Increase (comparison) of adjectives

The modern Greek adjective can be in four different degrees of improvement (degrees of comparison).

- The positive: oreos (ωραίος 'beautiful')

- The comparative: pio oréos, oreó ter os ( πιο ωραίος, ωραιό τερ ος 'more beautiful')

- The superlative: o pio oréos, o oreó ter os (ο πιο ωραίος, ο ωραιό τερ ος 'the most beautiful')

- The elative : polý oréos, oreó tat os ( πολύ ωραίος, ωραιό τατ ος 'very beautiful')

The levels of comparison can be formed in two different ways, by deriving it by adding the suffix 'ter' (τερ) in the comparative and superlative or 'tat' (τατ) in the elative or by paraphrasing the positive with the adverb pio (πιο, more ') for the comparative or' poly '(πολύ' very ') for the elative. In both variants, the superlative is formed by adding the specific article.

The KNG congruence also remains with the forms of the adjective. Adding the suffixes can shift the stress in the root of the word. For some very frequently used adjectives such as “good” (καλός), “large” (μεγάλος) or “small” (μικρός) there are irregular forms. Some loanwords and a class of vernacular adjectives that end in ύς or ης can only be increased by the circumscribing variant with πιο.

pronoun

Personal pronouns

In modern Greek, a distinction is made between weak and strong personal pronouns; weak ones predominate in terms of frequency of use. In some cases both types of pronouns are used together. The 2nd person plural serves as a form of politeness .

Strong personal pronouns

The strong personal pronouns are mainly used for the purpose of stressing and emphasizing opposites , also after prepositions and in unprecedented sentences.

| Singular | Plural | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st person | 2nd person | 3rd person (masc. Fem. Neutr.) | 1st person | 2nd person | 3rd person (masc. Fem. Neutr.) | |

| Nominative | egó (εγώ) | esý (εσύ) | avtós, avtí, avtó (αυτός, αυτή, αυτό) | (e) mís (ε) μείς) | (e) sís ((ε) σείς) | avtí, avtés, avtá (αυτοί, αυτές, αυτά) |

| Genitive | eména (εμένα) | eséna (εσένα) | avtoú, avtís, avtoú (αυτού, αυτής, αυτού) | emás (εμάς) | esás (εσάς) | avtón, avtón, avtón (αυτών, αυτών, αυτών) |

| accusative | eména (εμένα) | eséna (εσένα) | avtón, avtí (n), avtó (αυτόν, αυτή (ν), αυτό) | emás (εμάς) | esás (εσάς) | avtoús, avtés, avtá (αυτούς, αυτές, αυτά) |

Examples

- Highlighting: FTEO EGO (Φταίω εγώ , I 'm to blame ')

- Contrasting: Akoús aftón i aftín? (Ακούς αυτόν ή αυτήν ; 'Do you hear him or her ')

- Uncategorized : Piós pléni? Esý! ( Ποιός πλένει; Εσύ ! ' Who is washing up? You !')

- After preposition: To korítsi írthe s' eména (Το κορίτσι ήρθε σ΄ εμένα 'The girl came to me ')

Weak personal pronouns

The weak personal pronouns are one of the few elements of the modern Greek language that are subject to strict rules regarding the order of sentences. For more information, see below under "Sentence Positioning".

| Singular | Plural | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st person | 2nd person | 3rd person (masc. Fem. Neutr.) | 1st person | 2nd person | 3rd person (masc. Fem. Neutr.) | |

| Nominative | - | - | tos, ti, to (τος, τη, το) * | - | - | ti, tes, ta (τοι, τες, τα) * |

| Genitive | mou (μου) | sou (σου) | tou, tis, tou (του, της, του) | mas (μας) | sas (σας) | tous, tous, tous (τους, τους, τους) |

| accusative | me (με) | se (σε) | ton, ti (n), to (τον, τη (ν), το) | emás (μας) | esás (σας) | tous, tis / tes, ta (τους, τις / τες, τα) |

* The nominative of the weak forms is only used in the third person and only in fixed word additions such as Na tos (Νάτος! 'There he is !').

Examples

- Enclitic use of personal pronouns (directly after the finite verb) in the real imperative:

- Pes mou ! (Πες μου ! 'Tell me !')

- Proclitic use of personal pronouns (just before the finite verb) as an object:

- Sou gráfo. ( Σου γράφω. 'I am writing to you .')

Categories and elements of the verb phrase

The modern Greek finite verb has various person and number differentiating inflection schemes for the grammatical categories of the verb gender , aspect and time stage .

The aspect is mostly indicated by changes to the verb stem itself or by inserting a / s / sound into the sound sequence between stem and ending. The past and present time stages have different series of endings; in addition, in all but one declination scheme (Paratatikos of the end-stressed verbs), the forms of the past are marked by shifting the stress to the third from last syllable. The future tense and the conditional are analytically formed by placing the particles tha (θα) or na (να) in front. Also, the perfect tense time forms are circumscribed by the combination auxiliary and an undiffracted Aparemfato formed. The modern Greek "passive" emerged from the mediopassive forms of ancient Greek and follows a conjugation scheme with its own series of endings in the time stages of the present and the past.

The semifinite (imperative - only in the 2nd person singular and plural) and infinite (e.g. the present participle active) verb forms contrast with these finite categories, i.e., expressing person and number.

Person and number

- πρόσωπο & αριθμός

The modern Greek finite verb conjugates in congruence to the sentence subject in the first to third person in singular and plural . The rudimentary dual in ancient Greek has completely disappeared in modern Greek.

Time step

- χρόνος

There are three time levels: The past (παρελθόν), the present (present, ενεστώτας) and the future (future, μέλλοντας).

aspect

- τρόπος, ρηματική άποψη

The modern Greek verb expresses one of the three possible verbal aspects in almost all of its forms. An action or a happening is categorized by the aspects according to the degree of completion or according to the type of their chronological sequence.

- After an action is completed, it is viewed in terms of its effects on narrative time. This aspect is called perfect (Greek: εξακολουθητική άποψη).

- An action is categorized as continuous or repetitive at narrative time. This aspect is called imperfect , paratatic or continuous (Gr .: στιγμιαία or μη-συνοπτική άποψη)

- An action is viewed as momentary, punctual. This aspect is called perfective , aoristic or punctual (Greek: συντελεσμένη or συνοπτική άποψη).

The fact that the temporal stage of the present is understood in principle as being in the process explains the lack of a “punctual” present tense. However, since the aspect distinction is again mandatory in the usual subordinate clause formation as a modal statement, the aspect distinction is also omnipresent in everyday language (see Ypotaktiki ).

Since an aspect distinction in this sense is alien to the German language, its use can best be demonstrated with examples; the irregular verb for 'see' makes the aspect distinction in the past particularly clear:

- Imperfect: Kathe chimona evlepa ta chionismena vouna. "Every winter I saw the snow-covered mountains."

- Perfect: Chtes ton ida to Gianni . " I saw Hans yesterday ."

In the verb for “see”, the tenses Paratatikos and Aorist use not only a modified but a completely different verb stem for the same term.

- Differentiation of aspects in the imperative (command form)

- Imperfect: Panda prose ch e sto dromo! "Always watch out for the road!"

- Perfect: An to psonisis, prose x e tin timi! "If you buy this, pay attention to the price!"

- Differentiation of aspects in the future tense

- Imperfect: Tha sou gra f o kathe mera "I will write to you every day."

- Perfect: Avrio tha gra ps o ena gramma gia ti mana mou. "Tomorrow I'll write a letter to my mother."

- Differentiation of aspects in the "Ypotaktiki"

- Imperfect: Thelo panda na pinis polý neró "I want you to always drink a lot of water"

- Perfect: Thelo na piís polý neró avrio "I want you to drink a lot of water tomorrow"

On the terminology of the aspect names

For the verbal category 'aspect', which does not exist in German grammar, the specialist literature uses a non-uniform terminology, terms such as “perfect”, “perfect” and “perfect” appear in different meanings, the terms for the aspects are in the literature inconsistent and sometimes even contradicting.

Most of today's Indo-European languages have the originally three-part system of aspects reduced to only two aspects (imperfect / incomplete and perfect / completed) or even completely, whereas modern Greek continues to use all three aspects. Hans Ruge describes them in his "Grammar of Modern Greek" as "perfect", "imperfect" and "perfective", the former standing for the resulting tenses perfect , past perfect and perfect future and the latter for the tenses formed with the aorist stem. In publications that do not deal with the Greek language, but z. For example, when dealing with the Slavic languages, the perfective aspect is often called 'perfect'.

Tempora: time level and aspect

Modern Greek has a combined system of temporal stage and verbal aspect, ie each “tense” paradigm expresses both a temporal stage and an aspect. Except in the present tense - and only in main clauses - the speaker has to decide in which aspect he wants to express what has been said. In the following section, the term “tense” is therefore used as a designation for a verbal cardigma, which carries both information, and not as a designation only for the time level.

| completed | ongoing | currently | |

|---|---|---|---|

| future | perfect future tense | continuous future tense | current future tense |

| present | Perfect | Present | |

| ("Ypotaktiki") | - | "Conj. Present" | "Conj. Aorist " |

| past | past continuous | Paratatikos | Aorist |

The forms of the perfective are classified according to the time stage on which the completed actions or events have an impact. Therefore, the tense perfect is placed in the sequence of the present. (Make yourself aware that the statement of the sentence This bush has not yet blossomed relates to the present, although it refers to an event that (did not) take place in the past).

Ypotaktiki

The Ypotaktik sentence structure typical of modern Greek (literally 'subjunctive', but means main clause + subordinate clause followed by a modal particle with a verb in a grammatical subjunctive form) requires one of two other verb forms for the verb in the subordinate sentence. Since the “subjunctive” mode has long been realized differently in Modern Greek (see below), the traditional terms “conjunctive aorist” (υποτακτική αορίστου) and “subjunctive present” (υποτακτική του ενεστώτaα when considering their two functional occurrences) . These two “timeless” tenses, which syntactically replace the infinitive lost in modern Greek, create the separation of the punctual and the continuous aspect in modal subordinate clauses. In both cases, a modal particle is placed in front of the verb (mostly na , but also as ). The “conjunctive aorist” is by far the more common use case: Thelo na tre x o “I want to run”. Statements in the subjunctive present, on the other hand, are relatively rare due to the nature of their meaning: Prepi na tre ch o 5 km kathe mera, ipe o giatros mou. "I have to run 5 km every day, my doctor said."

Morphology of the tenses

The time stage is expressed by using different inflection series for the present and past, by shifting the emphasis to the third from last syllable (alternatively with two-syllable words by an advanced augment ) or by the prefix of the future tense particle θα (tha). The aspect , on the other hand, is expressed in the word stem used or the choice of the analytical perfect form. With a few exceptions, every modern Greek verb has several stems, a present or paratatic stem and an aorist stem for active and passive. The inflected endings marking the time stages are attached to this aspect-defining stem or the augment and the future tense particle “tha” are advanced.

Use of tenses

The use of tenses - both in terms of time and aspect - is more restrictive in modern Greek than in German. For the sentence “Tomorrow I will go to Giannis” the form of the future tense must be used, ie “Tomorrow I will go to Giannis” ( Avrio tha pao sto Gianni Αυριο Θα πάω στο Γιάννη). Since it is a one-time action, the punctual aspect must be used for the sentence. Even in simple colloquial situations, the use of the right aspect is mandatory - a "I want to pay" (θέλω να πληρώ ν ω) in the form of the imperfective aspect makes the host happy, but it is not the right thing if you only pay for the food that has just been consumed wants (θέλω να πληρώ σ ω), since one has said that from now on one will habitually always want to pay. The use of a perfect form for the mere representation of a past plot is also not possible, in the perfect aspect only one plot should appear, the effects of which on the narrative point should be particularly emphasized ("Although I had filled up, I ran out of gas shortly before Athens") .

Of the nine possible combinations of the three time stages and three aspects, eight are actually used in modern Greek, whereby the forms of the perfect aspect do not appear as often in the spoken language as the others. The present tense plays a special role: in the main clause, the verb with paratatic stem and present tense endings is always used, an aspect differentiation is not possible here . But both morphologically and semantically, the basic form of the present tense can be placed in the series of the imperfective aspect. The situation is different in subordinate clauses of a present tense statement, here the verb of the dependent clause is preceded by the particle “na” and the aspect differentiation is again given by using the different verb stems. The sentence construction known as “Ypotaktiki” is very common in Modern Greek, among other things because it serves as a replacement for the missing infinitive constructions. This sentence construction, which emerged from the desired or possible form, is mostly viewed as "free of time stages" and therefore not viewed as a complete tense in the above sense. In the table above, it is placed below the present tense.

imperative

- προστακτική

A distinction between aspects is also possible in the imperative , the command form of the verb. The imperative only exists productively in the second person singular and plural, an imperative of the third person ( zito! 'He live!') Can only be found in fixed idioms. In addition to the formation of the imperative through inflection, the somewhat more moderate-looking circumscribing formation using the particles na (να φας! 'Eat!') Is possible. The negation has to be expressed with the negation particle mi (n) (μη) ( min kles 'don't cry!').

Diathesis and gender verbi

- Διαθέσεις και Φωνές

Put simply, the diathesis ("direction of action") expresses (in the semantic sense) of a statement what role the grammatical subject of a sentence has in an action. The aim of the action is either another object ('Hans washes the car' - active ), the subject itself ('Hans washes himself' - reflexive ) or the subject itself is the target of an action carried out by others ('Hans is washed' - passive ). Another diathesis is, for example, the mutual action of several subjects on the other ('Hans and Maria push each other' - reciprocal ).

If there is a grammatical equivalent in the verb morphology for this semantic categorization of actions in a language , this is referred to as the gender verbi or verb gender . In German, verbs can be used in one of the two verb genders active or passive, other languages such as Sanskrit or Ancient Greek had another medium , which was mainly used for reflexive diathesis or for verbs of state.

In modern Greek, it is not the ancient Greek medium forms but the passive forms that have been lost, which is why passive diathesis is also expressed with the form group of the mediopassive genus Verbi. Because of these multiple use of the genus Medio-passive with various diathesis it is by linguist Hans Ruge in his "Grammar of Modern Greek" simply as non-active , respectively.

The modern Greek school grammar distinguishes four diatheses (“moods”) of the verb: ενεργητική διάθεση (acting, active), παθητική διάθεση (suffering, passive), μέήση, διάθεδη (medium, no action ιιτθεδη ιτεθ έιτθεδη ιτεθ ιτθεδη The two genera verbs are referred to as ενεργητική φωνή and παθητική φωνή (acting and suffering voice).

active

- ενεργητική φωνή

The grammatically active gender of a verb, for which both genera are possible, always expresses the active diathesis or, in the case of some intransitive verbs, the state of the subject.

Not active

- παθητική φωνή

The modern Greek non-active verb forms are morphologically derived from those of the ancient Greek medio-passive. In contrast to German, but analogous to Latin , these "passive" verb forms are inflected, that is, formed by their own verb endings and are not circumscribed with an auxiliary verb (in German eg "werden").

In many cases ( vlepome βλέπομαι, 'I will be seen') the non-active form expresses a meaning corresponding to the German passive. But due to the linguistic-historical development outlined above, many modern Greek verbs in the non-active genus Verbi do not have a passive, but a reflexive meaning: the active vrisko (βρίσκω) means 'I find', but the non-active vriskome (βρίσκομαι) does not mean 'I' will be found ', but rather' I am '. In this case, the actually passive “being found” must be paraphrased as active “they will find me”: Fovame oti me briskoun (Φοβάμαι οτι με βρίσκουν, 'I'm afraid that they will find me'). In addition, there is a large group of verbs from the areas of meaning of feeling, being and body care, the non-active of which always or context-dependent has a reflexive diathesis (see the examples below).

The auxiliary verb "to be"

The modern Greek equivalent of the auxiliary verb “sein” - ime (είμαι) is conjugated with a scheme based on the non-active series of endings: ime ise ine imaste iste ine.

Landfill

- αποθετικά

As in ancient Greek, there is also a group of verbs in modern Greek that can only be realized in the non-active gender verbi, i.e. for which there are no active forms. Such verbs are called Deponentien . Despite their grammatical form, they can in some cases express an active diathesis, but mostly they stand for the reflexive diathesis or for states. The most famous modern Greek depository is probably erchome (έρχομαι 'come') with its irregular imperative ela (ελα! 'Come!'). Logically, grammatical means can no longer be used to form a semantic passive from such dumps, since the passive form is already occupied by the basic word, in this case a speaker has to resort to lexical means.

Examples

- The grammatical passive of a "normal verb" has reflexive diathesis:

- O andras plenete Ο άντρας πλένεται. "The man washes himself." (If the subject is not a living being, on the other hand, the passive diathesis is assumed: "The car is washed.")

- To agori kryvete Το αγόρι κρύβεται. "The boy is hiding." (The passive voice "The boy is hidden" must be expressed by other means; the impersonal active construction "You hide the boy" is preferred)

- The grammatical passive of a "normal verb" has reciprocal diathesis:

- Mi talked! Μη σπρώχνεστε! "Don't push yourself!"

- Some deposits (i.e. the verb only exists as a grammatical passive) have active diathesis:

- erchome έρχομαι, stekome στέκομαι: "I'm coming." "I'm standing."

- Other deposits predominantly, but not exclusively, express the reflexive diathesis:

- thymame θυμάμαι, arnoume αρνούμαι, esthanome αισθάνομαι: "I remember." "I refuse." "I feel."

The verb

Conjugation tables

Exemplary the complete conjugation of the regular verb γράφω ( grafo "I write")

Non-compound forms in the imperfective (paratatic) aspect

| Active non-past | Active past | Non-past passive | Past passive | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Sg. | γράφ ω - graph o | έγραφ α - égraf a | γράφ ομαι - gráf ome | γραφ όμουν - count ómoun |

| 2nd Sg. | γράφ εις - gráf is | έγραφ ες - égraf es | γράφ εσαι - gráf ese | γραφ όσουν - count ósoun |

| 3rd Sg. | γράφ ει - gráf i | έγραφ ε - égraf e | γράφ εται - gráf ete | γραφ όταν - graf ótan |

| 1st pl. | γράφ ουμε - gráf oume | γράφ αμε - gráf ame | γραφ όμαστε - graf ómaste | γραφ όμασταν - graf ómastan |

| 2nd pl. | γράφ ετε - gráf ete | γράφ ατε - gráf ate | γράφ εστε - gráf este | γραφ όσασταν - graf ósastan |

| 3rd pl. | γράφ ουν - gráf oun | έγραφ αν - égraf an | γράφ ονται - gráf onte | γράφ ονταν - gráf ontan |

Modern Greek has many verbs, the conjugation scheme of which deviates considerably from the one shown above. In some cases, this is based on speech simplifications and sound loops in particularly frequently used verbs, but also the partial adoption of ancient Greek schemes in "learned" verbs. See also the article Irregular Verbs in Modern Greek .

Uncompounded forms in the perfective (aoristic) aspect

| Active non-past | Active past | Non-past passive | Past passive | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Sg. | γράψ ω - gráps o | έγραψ α - égraps a | γραφ τώ - graf tó | γράφ τηκα - graph tika |

| 2nd Sg. | γράψ εις - gráps is | έγραψ ες - égraps it | γραφ τείς - count tís | γράφ τηκες - gráf tikes |

| 3rd Sg. | γράψ ει - gráps i | έγραψ ε - égraps e | γραφ τεί - graf tí | γράφ τηκε - gráf tike |

| 1st pl. | γράψ ουμε - gráps oume | γράψ αμε - gráps ame | γραφ τούμε - count toúme | γραφ τήκαμε - graf tíkame |

| 2nd pl. | γράψ ετε - gráps ete | γράψ ατε - gráps ate | γραφ τείτε - graf títe | γραφ τήκατε - graf tíkate |

| 3rd pl. | γράψ ουν - gráps oun | έγραψ αν - égraps on | γραφ τούν - count toún | γράφ τηκαν - gráf tíkan |

Adverbs

- επιρρήματα

Adverbs are uninflected additions to the predicate of a statement such as 'very', 'soon', 'gladly' or 'fast', which specify the circumstances of an action more precisely in terms of time, space or modal. As in German, the predicate attribute or predicative uses the adjective: H Maria ine grigor i (Η Μαρία είναι γρήγορ η 'Maria is fast') versus H Maria troi grigor a (Η Μαρία τρώει γρήγορ ) Maria isst fast α '.

Adverbs derived from adjectives

An adverb derived from an adjective corresponds to the form after the nominative plural neuter of the adjective and can be increased according to the same scheme as adjectives.

Adjective: grigor os (γρήγορ ος 'fast') → Adverb: grigor a (γρήγορ α ) → Comparative: pio grigora (πιο γρηγορ α ) or grigoro ter a (γρηγορότερα)

The overwhelming number of modern Greek adverbs derived from adjectives therefore end with the sound / a /. A smaller group of adverbs derived from the declined adjectives on ys, on the other hand, forms the adverb with the older ending -ως ( os ). For some adjectives and thus also for the adverbs, both formations are possible, but this usually involves a difference in meaning, for example akriv os ('exactly') akriv a ('expensive').

Sentence structure

Word order

Word order in modern Greek sentences is basically free, with strong restrictions on particles and pronouns.

In the statement

As in the German statements, the case marking of subject (S) and object (O) allows a position before or after the predicate verb (V). In both languages, the first is the predominant one, but the second can be used for the purpose of emphasis:

- (SVO) I gata kynigai ti zourida. 'The cat chases the marten.'

- (OVS) Ti zourida kynigai i gata. 'The cat chases the marten.'

In contrast to German, the word order in the propositional sentence is not subject to the restriction that the finite verb must come second. This also enables the following word positions, which in German either mark a question or conditional sentence or, in the case of the verb ending, are only possible in the subordinate clause:

- (VSO) Kynigai i gata ti zourida. 'The cat chases the marten.'

- (VOS) Kynigai ti zourida i gata 'Chase the marten the cat.'

- (SOV) I gata ti zourida kynigai 'The cat chases the marten'

- (OSV) Ti zourida i gata kynigai 'The marten chases the cat'

In the question

Modern Greek does not specify any word order in the question, either, the question is only expressed through a changed intonation (raising the voice at the end of the sentence).

With weak personal pronouns

The position of weak personal pronouns in relation to their reference word is subject to strict rules, depending on their syntactic role. As a genitive attribute the pronoun is absolutely behind his main word ( I gata mou , My Cat ') as an object, however, necessarily before the finite verb ( Mou grafis , you write to me').

literature

Current grammars

- Georgios N. Chatzidakis : Introduction to Modern Greek Grammar . Leipzig 1892, reprint: Hildesheim / Wiesbaden 1977 (Library of Indo-European Grammars, 5).

-

Peter Mackridge , David Holton , Irene Philippaki-Warburton : Greek. A comprehensive grammar of the modern language. Routledge, London 1997, (excerpts online) .

- Greek translation: Γραμματική της Ελληνικής γλώσσας. Patakis, Athens 1999.

- Peter Mackridge, David Holton, Irene Philippaki-Warburton: Greek. An essential grammar of the modern language. Routledge, London 2004, ISBN 0-415-23210-4 , (online) (PDF); (another copy online) .

- Greek translation: Βασική Γραμματική της Ελληνικής γλώσσας. Patakis, Athens 2007.

- Hubert Pernot : Grammaire grecque modern. Première partie. Garnier frères, Paris 1897, reprinted several times, ND 4th edition. 1912 (online)

- Hubert Pernot, with Camille Polack: Grammaire du grec modern (Seconde partie) . Garnier Frères, Paris 1921, (online)

- Γ. Μπαμπινιώτης, П. Κοντός: Συγχρονική γραμματική της Κοινής Νέας Ελληνικής. Athens 1967.

- Hans Ruge : Grammar of Modern Greek: Phonology, Form Theory, Syntax. Third, expanded and corrected edition, Romiosini Verlag , Cologne 2001 (2nd edition 1997, 1st edition 1986), ISBN 3-923728-19-0 .

- Albert Thumb : Manual of the modern Greek vernacular. Grammar, texts, glossary. Strasbourg 1910.

- Henri Tonnet : Précis pratique de grammaire grecque modern. Langues et mondes, Paris 2006.

- Μανόλης Τριανταφυλλίδης : Νεοελληνική Γραμματική (της Δημοτκής) . Thessaloniki 1941, reprints 1978 (with a Επίμετρο), 1988, 1993, 2002 (Ανατύπωση της έκδοσης του ΟΣΕΒ (1941) με διορθώσεις: new edition of the original edition from 1941 with corrections)

- Manolis Triantaphyllidis: Μικρή Νεοελληνική Γραμματική. Athens 1949.

- Νεοελληνική Γραμματική. Αναπροσαρμογή της μικρής Νεοελληνικής Γραμματικής του Μανόλη Τριανταφυλλίδη. Οργανισμός εκδόσεως διδακτικών βιβλίων. Athens 1976 (online) (PDF).

- Μαρία Τζεβελέκου, Βίκυ Κάντζου, Σπυριδούλα Σταμούλη: Βασική Γραμματική της Ελληνικής. Athens 2007, (online) (PDF).

- Pavlos Tzermias : Modern Greek grammar. The theory of forms in the vernacular with an introduction to phonetics, the origin and the current state of modern Greek. Bern 1969.

Older grammars

-

Émile Legrand (eds.): Νικολάου Σοφιανοὺ τοῦ Κερκυραίου Γραμματικὴ τῆς κοινῆς τῶν Ελλήνων γλώσσης νῦν τὸ πρῶτον κατὰ τὸ ἐν Παρισίοις χειρόγραφον ἐκδοθεῖσα ἐπιμελείᾳ και διορθώσει Αἰμυλίου Λεγρανδίου. Ἐν τῷ γραφείῳ τῆς Πανδώρας, Ἀθήνησιν and Maisonneuve, Paris 1870 (Collection de monuments pour servir à l'étude de la langue neo-hellénique, no.6: Grammaire de la langue grecque vulgaire par Nikolaos Sophianos), (online) (PDF)

- Extended second edition under the title: Nicolas Sophianos , Grammaire du grec vulgaire et traduction en grec vulgaire du Traité de Plutarque sur l'éducation des enfants. Maisonneuve, Paris 1874, (online) ; (another copy online) (PDF). - Review by Bernhard Schmidt, in: Jenaer Literaturzeitung. 1874, No. 35, pp. 568-569, (online) .

-

Vocabolario italiano et greco, nel quale si contiene come le voci Italiane si dicano in Greco volgare. Con alcune regole generali per quelli che sanno qualche cosa di Gramatica, acciò intendano meglio il modo di declinare, & coniugare li Nomi, & Verbi; & habbiano qualche cognitione della Gramatica di questa lingua Greca volgare. Composto dal P. Girolamo Germano della Compagnia di GIESV. In Roma, per l'Herede di Bartolomeo Zannetti 1622, (online) ; (another copy online) .

- Hubert Pernot (ed.): Girolamo Germano: Grammaire et vocabulaire du grec vulgaire publiés d'après l'édition de 1622. Fontenay-sous-Bois 1907 (thèse supplémentaire présentée à la faculté des lettres de l'Université de Paris), ( online) . - Contains a detailed introduction to the history of modern Greek grammar and lexicography up to the 19th century. - Advertisement by R. Bousquet, in: Échos d'Orient. 11, no. 72, 1908, pp. 317-318, (online) .

- Simon Portius (Simone Porzio): Grammatica linguae graecae vulgaris. Reproduction de l'édition de 1638 suivie d'un commentaire grammatical et historique par Wilhelm Meyer with an introduction de Jean Psichari . E. Bouillon et E. Vieweg, Paris 1889, (online) .

-

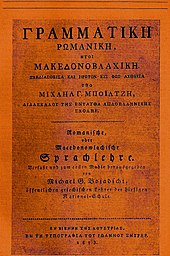

Γραμματική Ρωμανική ήτοι Μακεδονοβλαχική. Romance or Macedonoslach language teaching . Written and published for the first time by Michael G. Bojadschi , Vienna 1813 (231 pages) (German and Greek); 2nd edition, Bucharest 1863.

- Gramaticã românã sau macedo-românã . Bucharest 1915.

- Romance or Macedonovlach language teaching. Γραμματική Ρωμανική ήτοι Μακεδονοβλαχική [extract from Greek and German], in: Aromanian studies . Salzburg 1981 (Studies on Romanian Language and Literature, 5).

- Gramaticā aromānā icā macedonovlahā . Edited by VG Barba, Freiburg im Breisgau 1988, excerpt .

- Concise modern Greek language teaching together with a collection of the most necessary words, a selection of friendly conversations, idioms, proverbs and reading exercises; first for the Greek youth in the Austro-Hungarian states, and then for Germans who want to make this language their own, intended = Σύντομος γραμματική της γραικικής γλώσσης . Vienna 1821 (380 pages), (online)

- Paul Anton Fedor Konstantin Possart : Modern Greek grammar together with a short chrestomathy with a dictionary, for school and private use. Edited by Dr. Fedor Possart. At Herrmann Reichenbach, Leipzig 1834, (online) .

- Friedrich Wilhelm August Mullach : Grammar of the Greek vulgar language in historical development. Berlin 1856, (online) .

Web links

- moderngreekverbs.com: Modern Greek Verbs (in 235 conjugation models , in English)

- schwadlappen.de: Modern Greek: Vocabulary - learning aids - information

Individual evidence

- ↑ Nomenclature for the declension schemes according to Ruge