Heini Mader Racing Components

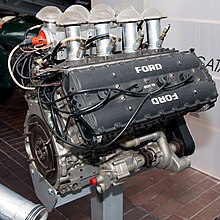

Heini Mader Racing Components (short: Mader) is a Swiss tuner and manufacturer of racing engines. The company, which has been based in Gland in the canton of Vaud for many years , emerged from the Joakim Bonnier Racing Team and has been known in particular as a processor of BMW and Cosworth engines for Formula 1 , Formula 2 and Formula 3000 since the 1970s . The long-time owner Heinrich "Heini" Mader is often referred to in motorsport circles as the "Cosworth Guru". After a change of ownership at the beginning of the 21st century, the company now manufactures engines for the GP2 series and endurance racing, among other things .

Company history

Background: Heini Mader, Jo Siffert and Joakim Bonnier

Heini Mader, born in Lindau in 1936, worked in the early 1960s as a mechanic for Heinz Schiller , who won the European Hill Climbing Championship in 1961 . Through Schiller, Mader got to know the Swiss racing driver Jo Siffert , who was under contract with the Scuderia Filipinetti and competed for the Geneva racing team in the 1962 World Cup with a Lotus 24 . That year Mader took care of Siffert's car as a mechanic. When Siffert founded his own racing team in Freiburg the following year , Mader joined the Siffert Racing Team . The collaboration ended when Siffert got a job with the British Rob Walker Racing Team in 1965 . From 1968 Mader worked for the Swedish racing driver Joakim Bonnier , who at that time was building his own racing team on Lake Geneva . The company, mostly registered as Joakim Bonnier Racing Team, officially traded as Bonnier Inter SA. Mader accompanied Bonnier's engagements in various motorsport classes for four years. After Bonnier's fatal accident at the 1972 Le Mans 24-hour race , Mader took over Bonnier Inter SA in the late summer of 1972 and renamed it Heini Mader Racing Components in 1974. The company kept its headquarters in Gland for the next four decades.

Mader and BMW

Formula 2

Mader's relationship with BMW began in the Formula 2 European Championship . BMW has been supplying four-cylinder M12 / 6 engines exclusively to the Formula 2 works team of the British chassis manufacturer March since 1973 . Little by little, the engines became available to other teams, and since the mid-1970s, BMW designs were the most widely used drive unit in the European series. However, the March team continued to receive factory-prepared engines, which were sometimes referred to as BMW-Rosche based on the designer Paul Rosche . The other BMW customers were dependent on maintenance and tuning by independent specialist companies, unless they - like Osella - did the engines themselves. After Schnitzer had already developed its own versions of the M12 / 6 in 1973, Mader began looking after BMW customer engines in the second half of the 1970s. Mader competed here with Novamotor and Amaroli from Italy and Heidegger from Liechtenstein, among others . In the early 1980s, Mader was the most frequently commissioned tuning company for the Formula 2 European Championship. In the 1984 season, Mader supplied 11 of the 15 teams that registered for the championship races that year, including AGS , Minardi and, most recently, Onyx . In the last year of the championship, however, Mader's four-cylinder were considered prone to failure and inferior to the Honda engines prepared by John Judd . One of the reasons for this was the extension of the revision intervals that Mader had agreed to in order to counter the cost explosion that Formula 2 suffered from in its final years.

With the end of the Formula 2 European Championship after the end of the 1984 season, there was no longer any need to overhaul these BMW engines. In the successor series, the International Formula 3000 Championship , Mader continued his involvement with Cosworth DFV engines.

formula 1

Since 1981 BMW has also been represented in the Formula 1 World Championship with a turbo engine based on the M12. Initially, the British Brabham team received the engines exclusively. In 1983 and 1984 , ATS and Arrows were added as customer teams, and in 1986 the Toleman successor Benetton Formula also drove with BMW engines. While BMW was maintaining the Brabham engines itself, the engines for Arrows and Benetton, which were still identical at the time, had been prepared by Mader since 1984, who benefited from years of experience he had gained in Formula 2 with the BMW block.

From 1986 onwards, the BMW works engines for Brabham differed from the engines that the customer teams received. For this season, BMW developed a particularly low engine design that was installed “horizontally” at an incline of 72 degrees and was tailored to Gordon Murray's flat Brabham BT55 . The customer teams, however, continued to drive with the previous M12 motors, now referred to as “standing”, which Mader continued to look after. Benetton Formula with the Mader engines was the most successful of all BMW teams this year: While Brabham only scored two world championship points during the entire season, Benetton scored 19 points and finished sixth in the constructors’s championship. At the 1986 Mexican Grand Prix, Benetton driver Gerhard Berger was the first to win a Formula 1 world championship race with a Mader engine.

For the 1987 season , BMW completely stopped production of the “standing” M12 engines. USF & G, a sponsor of the Arrows team, then acquired the rights to the construction and had it further developed by Mader. They were reported under the name Megatron for Arrows in 1987 and 1988 . Also in 1987, the Mader engines were superior to the factory engines for Brabham. This year Mader and Megatron also stepped in as engine suppliers for the Équipe Ligier , after their connection with Alfa Romeo had failed just before the start of the season. Finally, Mader and Megatron were also intended as engine suppliers for the Middlebridge-Trussardi project, which was ultimately not approved . In 1988 Maders BMW engines were only used on Arrows. At that time, Mader was already concentrating on the machining of Cosworth naturally aspirated engines in Formula 1.

Mader and Cosworth

formula 1

In the 1970s, Cosworth's DFV eight-cylinder engine was the most widely used power unit in Formula 1. For reasons of capacity, Cosworth could not maintain all of the engines in circulation. The service was outsourced to various independent companies early on, including John Judd's Engine Developments, Hart Racing Engines , John Wyer Automotive , Langford & Peck and Swindon Race Engines in Great Britain. In the mid-1970s, Heini Mader Racing Components was added, with mainly continental European teams being looked after. Maders Cosworth engines had an above-average reputation in the late 1970s. The dominance of turbo engines from 1983 to 1986 resulted in a brief hiatus from Mader's Cosworth-1 program. From 1986 to 1988 Mader was represented in Formula 1 with BMW engines under the Megatron label.

When the FIA allowed naturally aspirated engines again from 1987 , Cosworth returned to Grand Prix racing with a 3.5 liter version of the DFV called DFZ. Unlike in the 1970s, however, the eight-cylinder was no longer the standard engine in Formula 1: On the one hand, the top teams had exclusive engine partnerships with major manufacturers ( McLaren with Honda, Williams with Renault ), on the other hand, there were now competitive alternatives for the smaller teams to the Cosworth customer engines that came from Judd, Ilmor or Lamborghini . From 1988 Cosworth concentrated on the preferred customer Benetton, for whom the DFZ was further developed into the HB series via the DFR. The customer teams, on the other hand, were dependent on independent tuners as intermediaries between them and Cosworth. Cosworth did not allow the motors to be worked on independently, as Osella strived for in particular. Initially Mader was the only tuning company for DFZ engines, later Hart, Langford & Peck and Tom Walkinshaw Racing were added. Mader had a dominant position until 1990. Mader's customers in these years included AGS (1987–1991), Scuderia Italia (1988–1990), Coloni (1987–1989), EuroBrun (1988), Larrousse (1987–1988), March (1987), Minardi (1988 -1990), Onyx or Monteverdi (1989-1990), Osella (1989) and Rial (1988-1989).

As in the 1970s, Mader received the engines from Cosworth in kit form. This gave the company the opportunity to develop the DFZ independently. According to observers, Mader went further than his competitors. Mader varied the ignition systems and valve positions, among other things. At times there was a collaboration with the British technology company Tickford , in which a five-valve cylinder head was developed, which, however, was not used. In 1989 and 1990 , several expansion stages of the Mader motors were in use: pure DFZ versions, further developed DFR blocks and various intermediate models.

Mader's Formula 1 involvement ended in 1992 when the DFR engines could no longer find any customer teams.

Formula 3000

In 1985, the FIA replaced Formula 2, which was part of Formula 1, with the newly established Formula 3000. In this class, the International Formula 3000 Championship in Europe, and also the British Formula 3000 Championship and the Japanese Formula 3000 Championship (later: Formula Nippon ) held. The reason for the introduction of the new class was the recent sharp rise in the costs of Formula 2, which had led to a dominance of the works teams and a continuous decline in the number of participants since the early 1980s. The Formula 3000 regulations stipulated the use of the widespread and uncomplicated 3.0-liter naturally aspirated engines that were obsolete in Formula 1 because, from 1985, only turbo engines were used there. This resulted in a continued demand for Cosworth DFV motors, at least in Europe. In Japan, however, the Cosworth engines played practically no role; engines from Honda and Yamaha dominated there .

The care of the Cosworth engines for the continental European Formula 3000 teams was mainly done by Mader, while Swindon was initially preferred in Great Britain. In the 1986 European season , Ivan Capelli won the championship with Genoa Racing and a Mader-Cosworth. After that, Japanese Mugen engines dominated the European series for three years , partly because Mader neglected the Formula 3000 program in favor of the Formula 1 engines during this time. After the Formula 1 business came to a standstill at the end of 1991, Mader once again intensified the further development of the DFV engine for the Formula 3000. This was first noticeable in autumn 1991 when Forti driver Emanuele Naspetti took part in four races in a row a Mader-DFV. However, since he did not score any championship points in the other races, Naspetti only finished third in the championship, although he was temporarily in first place in the interim standings. However, that made him the best Cosworth pilot of the year. The following year , Luca Badoer , who drove a Reynard 92D for Crypton Engineering , became Formula 3000 champion with a Mader DFV. After that, the DFV motors increasingly lost their importance. Cosworth replaced them with expensive AC-type constructions specially tailored to the Formula 3000, which Mader rarely worked on.

Historic racing

In the 1990s, Mader increasingly shifted to looking after DFV engines for use in historic racing.

Mecachrome and successors

In November 2003, Mader sold his company to the French engine manufacturer Mecachrome , which relocated its headquarters to Nyon on Lake Geneva in November 2014 . From 2005, Mecachrome had, among other things, the engines for the GP2 series manufactured in the old Mader factory; Eight-cylinder naturally aspirated engines are also produced there for the LMP2 prototypes of the endurance world championship.

Only the Cosworth Formula 1 engine department remained with Heini Mader. Maders, the newly founded company HMR Sarl, which is still based in Gland, will take care of maintenance and the associated spare parts trade.

literature

- Adriano Cimarosti: The Century of Racing . Motorbuch Verlag, Stuttgart 1997, ISBN 3-613-01848-9 .

- Eberhard Reuss, Ferdi Kräling: Formula 2. The story from 1964 to 1984 . Delius Klasing, Bielefeld 2014, ISBN 978-3-7688-3865-8 .

- Gilles Liard: Jo Siffert: a fast life . Saint-Paul, 2008, ISBN 978-3-7228-0751-5 .

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Gilles Liard: Jo Siffert: a fast life , Saint-Paul, 2008, ISBN 978-3-7228-0751-5 , pp. 88-90.

- ↑ Heini Mader's biography on the website www.oldracingcars.com (accessed on November 5, 2018)

- ↑ Eberhard Reuß, Ferdi Kräling: Formula 2. The story from 1964 to 1984 , Delius Klasing, Bielefeld 2014, ISBN 978-3-7688-3865-8 , p. 193.

- ↑ Mike Lawrence: March, The Rise and Fall of a Motor Racing Legend , MRP, Orpington 2001, ISBN 1-899870-54-7 , p. 169.

- ↑ Adriano Cimarosti: The century of racing , motor book publisher Stuttgart 1997, ISBN 3-613-01848-9 , S. 358, 360th

- ↑ Adriano Cimarosti: The century of racing , motor book publisher Stuttgart 1997, ISBN 3-613-01848-9 , p 358, 373rd

- ^ History of Megatron on the website www.grandprix.com (accessed November 7, 2018).

- ↑ Motorsport aktuell, issue 45/1987, p. 22.

- ↑ a b History of the Cosworth DFV on the website www.research-racing.de, s. there the section "The Tuner" (accessed on November 8, 2018).

- ↑ Adriano Cimarosti: The century of racing , motor book publisher Stuttgart 1997, ISBN 3-613-01848-9 , S. 383rd

- ^ History of the Cosworth DFV on the website www.research-racing.de (accessed on November 6, 2018).

- ^ Reuss, Ferdi Kräling: Formula 2. The story from 1964 to 1984 , Delius Klasing, Bielefeld 2014, ISBN 978-3-7688-3865-8 .

- ^ David Hodges: Rennwagen from A – Z after 1945 , Stuttgart 1993, ISBN 3-613-01477-7 , p. 273.

- ^ NN: Fortification . Motorsport Magazine, October 1991, p. 46.

- ↑ Simon Arron: The Crypton Factor . Formula 3000 Review 1992. In: Alan Henry: Autocourse 1992/93. London 1992 (Hazleton Securities Ltd.), ISBN 0-905138-96-1 , pp. 250-253.

- ^ Gilles Liard: Jo Siffert: a quick life , Saint-Paul, 2008, ISBN 978-3-7228-0751-5 , p. 86.