Holland House (London)

Holland House , originally Cope Castle , was one of the first city palaces to be built in the London borough of Kensington and is located in Holland Park . In 1605 the building was built for the diplomat Sir Walter Cope in Jacobean style and in the following years belonged successively to the Rich and Fox families. When owned by the noble Fox family in the 19th century, it became a popular social gathering place for the Whigs . The house was largely destroyed during the German bombing raids on London in 1940, and today only the east wing and the ruins of the first floor remain.

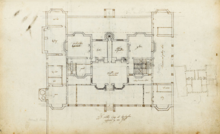

planning

In 1604 Walter Cope commissioned the architect John Thorpe to plan the house. It was given the appearance customary at the time: a central wing and two vestibules. It was built of bricks, with decorations of stucco and stone; the porch was in the shape of a tower

Between 1625 and 1635, on the instructions of Cope's son-in-law and new owner of the house, Henry Rich, 1st Earl of Holland , two wings and arcades were added. The house received two side wings with arcades on either side of the main wing. There were several libraries in the building. In 1629, Rich instructed architect Inigo Jones to design Doric-style pillars from Portland stone to support the house's large wooden gates, carried out by stonemason Nicholas Stone . The pillars that still exist today have been repositioned several times over the years.

Presumably there was also a chapel of its own at the time, but only remains of it exist. There was a bronze holy water fountain that later stood on the staircase of the hall, which apparently dates back to 1484 and was created by a Flemish artist.

history

17th century

At the time of its construction, Holland House stood on 200 acres of land that stretched between Holland Park Avenue and what is now Earl's Court Underground Station , on which exotic trees imported by John Tradescant the Younger were planted.

After the completion of the house, Cope entertained King James I and Queen Anne and also his son Prince Charles , granddaughter Princess Elizabeth and Elector Friedrich von der Pfalz several times .

After Cope's death in 1614, the property was inherited by his daughter Isabella, who was married to Henry Rich, 1st Earl of Holland, and the building was renamed Holland House .

The Earl of Holland was executed for his royalist activities during the English Civil War , and the building henceforth served as the military headquarters, which was regularly visited by Oliver Cromwell .

During the reign of King Wilhelm III. (1689–1702) Holland House was the king's domicile for a short time. William III. suffered from asthma and his health deteriorated at the Palace of Whitehall , which was near the Thames and in the middle of the bad air city. In the end he decided to buy Kensington House , the city residence of Heneage Finch, 1st Earl of Nottingham , now known as Kensington Palace .

18th century

In the time between the restoration and the reign of the House of Hanover , Holland House was rented to different parties, sometimes even divided into several apartments. Famous residents included Joseph Addison , who married the widow of the previous owner Edward Rich, 7th Earl of Warwick and died in the house in 1719, William Penn , Arthur Annesley, 1st Earl of Anglesey and Jean Chardin .

At the time of its greatest expansion, the land around Holland House covered over 200 acres and extended south to what is now Fulham Road . When Henry Fox, 1st Baron Holland bought it in 1768 from William Edwardes , who was in great debt, the size of the entire property had shrunk to around 80 hectares .

Fox had lived in the mansion since 1746, and in 1749 leased the Edwardes family home and 26 acres of land for "99 years or three lives." In 1767 Fox leased the entire property of the Edwardes north of Hammersmith Road (now Kensington High Street ) and later bought it for a total of 19,500 pounds, which he paid to the sons of Edward Henry Edwardes , who would have inherited the property after his death. Fox died in Holland House in 1774 and bequeathed the house and estate to his descendants.

19th and 20th centuries

Under Henry Vassall-Fox, 3rd Baron Holland and his wife Elizabeth , Holland House became a glamorous social, literary and political meeting place with many famous visitors including Lord Byron , Thomas Macaulay , Thomas Campbell , Benjamin Disraeli , Charles Dickens and Sir Walter Scott . Historian John Allen was so frequent in the house that he was called Holland House Allen and there was also a room in the house with his name on it. The diary writer Charles Greville wrote about the house: "It is the house of all Europe." In March 1804, the duel between Thomas Pitt, 2nd Baron Camelford and Captain Best took place on the property , which Pitt did not survive.

When Lady Elizabeth Holland was on a trip to Madrid , she received the seeds or roots of dahlias from the Spanish botanist Antonio José Cavanilles . She sent these to her husband's librarian, Serafino Buonaiuti, to England, who successfully planted them. This was one of the first known dahlia plantings in England .

The widow's residence belonging to the house, called Little Holland House , was an art salon in Victorian times , where artists, chaired by the Prinsep family and the painter George Frederic Watts , met.

Harper's New Monthly Magazine wrote in 1877 about the Gilt Chamber (dt. Golden space ) called character rooms with wall drawings of naked above the fireplace: "The lower marbles of the fireplace were black, and the upper ones were Sienna; the capitals and bases of the columns and pilasters were gilt, and the groundwork from which all the glittering decoration rose was white. "(Eng." The marble below the chimney was black, the one above it was colored ; the chapters and the bases of the columns and Pilasters were gold, and the floor from which all this glittering decoration rose was white. ”) The Gilt Chamber stretched the full depth of the house and overlooked the vast gardens at the back.

With the death of Henry Edward Fox, 4th Baron Holland , in 1859 the title Baron Holland became orphaned . His widow continued to live at Holland House and gradually sold parts of the park that were being built on. In 1874 the property passed to a distant cousin, Henry Fox-Strangways, 5th Earl of Ilchester . Despite parcel sales, the property still had the largest private property in London, including Buckingham Palace, at the beginning of the 20th century . Every year the Royal Horticultural Society held flower shows there .

Destruction and today's condition

In 1940 King George VI visited and Queen Elizabeth the last great ball that was held at Holland House . A few weeks later, on September 7, 1940, the bombing of London by the Germans began. On September 27th, Holland House was hit by 20 incendiary bombs and mostly destroyed. Only the east wing and the library, which contained valuable books such as the Boxer Codex from the 16th century, remained intact.

In 1949, Holland House was given level 1 on the list of buildings under the Town and Country Planning Act 1947 , which recorded the buildings of special historical interest that had been damaged by the bombing.

The property remained burned out until 1952 when its owner, Giles Fox-Strangways, 6th Earl of Ilchester , sold it to London County Council . In 1965 it was transferred to the Greater London Council and, after its dissolution in 1986, to the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea .

Today there is a youth hostel in Holland House . The orangery serves as an exhibition space together with the adjoining former Summer Ballroom , which is now a restaurant. The former ice house is an art gallery; There are sports facilities on the site. In 1962, part of the property on which the Commonwealth Institute was built was sold.

Coordinates: 51 ° 30 ′ 9 ″ N , 0 ° 12 ′ 9 ″ W.

Individual evidence

- ^ A b c d Edward Walford: Old and New London . Volume 5. 1878. pp. 161-177 on British History Online . Retrieved August 4, 2013

- ↑ a b Geraldine Edith Mitton: "The Kensington District". In: Walter Besant (Ed.): The Fascination of London . London 1930. Retrieved August 4, 2013

- ↑ Walter Spiers: "Notes on the life of Nicholas Stone". In: AJ Finberg: The Walpole Society . Oxford University Press 1919. Volume 7, p. 8 Retrieved August 4, 2013

- ↑ a b Elizabeth Allen: “Cope, Sir Walter (1553? –1614)”. In: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

- ↑ Thomas Birch / Robert Folkestone Williams: The Court and times of James the First: illustrated by authentic and confidential letters, from various public and private collections. London 1848. Retrieved August 4, 2013

- ^ EA Webb: The records of St. Bartholomew's priory St. Bartholomew the Great, West Smithfield . 1921. pp. 292-296. Retrieved August 4, 2013

- ↑ Origins: From Jacobean mansion to Kensington Palace on hrp.org.uk.Retrieved August 4, 2013

- ^ A b c F. HW Sheppard: Survey of London: volume 37: Northern Kensington . 1973 Retrieved August 4, 2013

- ^ Charles Greville: The Greville Memoirs: A Journal of the Reigns of King George IV. And King William IV. 1887. p. 126. Retrieved August 4, 2013

- ↑ Stephen Ruttan: "The Vancouver / Camelford Affair" on Greater Victoria Public Library , January 2001 ( Memento of the original from August 29, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ James Forbes / John Russell Ford: Hortus woburnensis . 1833. p. 246 Retrieved August 4, 2013

- ^ Robert Hogg: The Dahlia; Its history and cultivation . Groombidge and Sons. 1853. p. 5 Accessed August 4, 2013

- ^ RA Salisbury: "Observations on the different Species of Dahlia, and the best Method of Cultivating them in Britain." In: Transactions of the Horticultural Society of London . 1/1808. P. 93

- ^ "Elizabethan and later English furniture". In: Harper's New Monthly Magazine . Volume 56. 12/1877. Pp. 23–24 Retrieved August 4, 2013

- ↑ The National Heritage List for England: List Entry: Holland House ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Retrieved August 4, 2013

- ↑ Listed buildings on victoriansociety.org.uk ( Memento of the original dated December 7, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Retrieved August 4, 2013

Web links

- Property plan (PDF)

- Archive film film by Pathé News about the destruction of Holland House after the bombing

- Photo from the undamaged library

- Photos from 1952: the inside of the house and workers are cleaning up .

- The Royal Borough of Kensington & Chelsea (RBKC) - Holland Park official website

- Opera Holland Park

- London Holland Park Youth Hostel

- The Belvedere Restaurant