Hypacrosaurus

| Hypacrosaurus | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

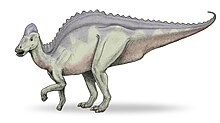

Skeletal reconstruction of Hypacrosaurus |

||||||||||||

| Temporal occurrence | ||||||||||||

| Upper Cretaceous ( Campanium to Maastrichtian ) | ||||||||||||

| 75 to 67 million years | ||||||||||||

| Locations | ||||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||||

| Hypacrosaurus | ||||||||||||

| Brown , 1913 | ||||||||||||

| species | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

Hypacrosaurus is a genus of ornithopod dinosaur from the group of hadrosaurs . It was similar to the related Corythosaurus - both genera showed a large, rounded hollow crest on the head, whereas the crest of Hypacrosaurus was not quite as large and straight. Two species have been named thatlived in North Americaduring the Upper Cretaceous 75 to 67 million years ago. Fossils have been found in Alberta ( Canada ) and Montana ( USA ).

Hypacrosaurus is the last representative of the Lambeosaurinae (hadrosaurs with a hollow crest) in North America, which is known for complete fossil finds. The type species Hypacrosaurus altispinus was first scientifically described by Barnum Brown in 1913 .

description

Hypacrosaurus can be distinguished from other Lambeosaurinae by the shape of the crest and the high spinous processes of the vertebrae. The spinous processes of the vertebrae are 5 to 7 times as high as the respective vertebral bodies , which leads to a high back. The hollow head comb is similar to that of the Corythosaurus , but tapers towards the top, is not so high, wider and has a small bony bulge on the back. In contrast to other Lambeosaurinae, the airways within the ridge did not have an S-curve. The animal probably reached a body length of 9.1 m and weighed about 4 tons. The postcranial skeleton is only slightly different from that of other hadrosaurs, although some features on the pelvic girdle are unique to Hypacrosaurus . Like all hadrosaurs, Hypacrosaurus was herbivorous and walked on both two and four legs. The two named species, Hypacrosaurus altispinus and Hypacrosaurus stebingeri , cannot be distinguished from other genera by individual, unique features ( autapomorphies ), since Hypacrosaurus stebingeri is regarded as a transitional form between the earlier Lambeosaurus and the later Hypacrosaurus .

Systematics

Within the Hadrosauridae, Hypacrosaurus is counted among the Lambeosaurinae . The closest relatives include Lambeosaurus and Corythosaurus . Jack Horner and Philip Currie (1994) suggest that Hypacrosaurus stebingeri is a transitional form between Lambeosaurus and Hypacrosaurus altispinus . Another study by Michael K. Brett-Surman (1989) considers Hypacrosaurus to be identical to Corythosaurus . In their new description of Nipponosaurus, Suzuki and colleagues (2004) suggest a close relationship between Nipponosaurus and Hypacrosaurus stebingeri and consider Hypacrosaurus to be paraphyletic . A recent study by Evans and Reisz (2007) contradicts this hypothesis, however, and sees Hypacrosaurus within a clade that includes Corythosaurus and Olorotitan as closest relatives, but not Nipponosaurus .

The cladogram shown here follows Evans and Reisz (2007) (simplified):

| Hadrosauridae |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Research history and naming

The holotype specimen was recovered for the American Museum of Natural History during an excavation under the direction of the famous paleontologist Barnum Brown in 1910 . The Fund, a fragmentary postkraniales skeleton consists of several vertebrae and a partial pool (copy number AMNH 5204), was the Red Deer River near Tolman Ferry in Alberta ( Canada discovered). The geological formation from which the find originated is now known as the Horseshoe Canyon Formation and is dated to the early Maastrichtian . Brown described these remains as a new genus in 1913, along with other postcranial bones, which he imagined to be similar to Saurolophus . At the time of the first description no skull was known; however, two skulls were soon discovered and described.

The name Hypacrosaurus ( Gr. Υπο -, hypo- = "smaller", "lesser"; ακρος , akros = "high" + σαυρος , sauros = "lizard") means something like "almost the highest lizard" and should refer to a Indicate animal that was almost, but not quite, as large as Tyrannosaurus .

In the period that followed, several taxa of particularly small lambeosaurins were described, but these are now considered to be young animals of various other lambeosaurins. The genus Cheneosaurus was established by Lawrence Lambe in 1917, based on a partial skeleton including skull, leg bones, vertebrae and pelvic bones from the Horseshoe Canyon Formation. Three years after describing Cheneosaurus , Richard Swann Lull and Nelda Wright identified a skeleton from the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH, specimen number 5461) from the Two Medicine Formation of Montana as a specimen of Procheneosaurus . These and other taxa were accepted as valid until the 1970s when Peter Dodson showed that they were juveniles of other established lambeosaurins. Dodson suspected that the "Cheneosaurus" specimens are likely to be regarded as juveniles of the contemporary Hypacrosaurus altispinus . Later publications followed this hypothesis. The Procheneosaurus specimen from the Two Medicine Formation is now considered a representative of the second Hypacrosaurus species, Hypacrosaurus stebingeri , described in 1994 .

species

Hypacrosaurus altispinus , the type species, is known from 5 to 10 skulls and associated parts of the postcranium discovered in the anatomical network . Hypacrosaurus stebingeri is known of remains belonging to numerous different individuals and spanning all ages, from embryos to adults.

Paleoecology

Hypacrosaurus altispinus comes from the Horseshoe Canyon Formation and its habitat is shared with the Hadrosauriern Edmontosaurus and Saurolophus , the small original ornithopods parksosaurus , the Ankylosauriden Euoplocephalus , the Nodosauriden Edmontonia , the horned dinosaurs Montanoceratops , Anchiceratops , arrhinoceratops and Pachyrhinosaurus , the Pachycephalosaurier Stegoceras , the ostrich-like ornithomimosaurs Ornithomimus and Struthiomimus , various little known, small theropods including troodontids and dromaeosaurids , as well as the tyrannosaurids Albertosaurus and Daspletosaurus . The Horseshoe Canyon Formation has a distinct marine character because of the Western Interior Seaway , an arm of the sea, which has been advancing again and again , which covered central North America during the Cretaceous. Hypacrosaurus altispinus probably lived more inland.

In the somewhat older Two Medicine Formation , from which the fossils of Hypacrosaurus stebingeri come, hadrosaurs were also represented by the genera Maiasaura and Prosaurolophus . Troodontid theropods are represented by troodons . Other theropods were the tyrannosauride Daspletosaurus , the Oviraptoride Chirostenotes and the dromaeosaurids Bambiraptor and Saurornitholestes . Herbivores were represented by the ankylosaurs Edmontonia and Euoplocephalus , the original ornithopod Orodromeus and the ceratopsian Achelousaurus , Brachyceratops , Einiosaurus and Styracosaurus . The depository of this formation was further away from the Western Interior Seaway, was higher and drier and was more terrestrial.

Paleobiology

Nests and Developmental Biology

A large number of fossil eggs, nests and young animals of the species Hypacrosaurus stebingeri have been described. These eggs were approximately round and 20 by 18.5 centimeters in size and contained embryos with a body length of about 60 centimeters. Freshly hatched animals were about 1.7 meters long. Young animals had deep skulls, the top of which showed only a slight elevation of the bones that formed the cranial crest in the adult animal. Using rings in cross-sections of long bones from periods of slow growth and the thickness of those bones, it was possible to reconstruct the growth pattern of this dinosaur. The growth was very fast in the first few years and was comparable to that of a ratite . After this strong growth phase, growth was not complete, but continued much more slowly. Studies by Lisa Cooper and colleagues on Hypacrosaurus stebingeri show that these animals reached sexual maturity at an age of 2 to 3 years and full size at around 10 to 12 years. The circumference of the femur at the presumed sexual maturity was approximately 40% of the final circumference of a fully grown animal. The presumed growth rate of Hypacrosaurus stebingeri exceeded that of tyrannosaurids such as Albertosaurus and Tyrannosaurus , putative predators of Hypacrosaurus , and may have developed due to the predator pressure in order to reach a height useful for defense as quickly as possible. Reaching sexual maturity early would also have been beneficial for prey.

Function of the head comb

The hollow head comb of Hypacrosaurus , like other lambeosaurins, presumably had social functions. It could have served as a visual identifier that allowed individuals to recognize representatives of a particular gender or their own species. In addition, it was probably used as a resonance body for generating sound signals.

Researchers working with John Ruben (1996) use the Hypacrosaurus head comb as an argument against the widespread research opinion that dinosaurs were endothermic (warm-blooded). As these researchers determine from computed tomography scans , Hypacrosaurus and two other dinosaur species studied by these researchers were likely lacking a certain type of turbinate that functions to prevent water loss when breathing. Today this type of turbinate is only found in endothermic animals - mammals and birds - but not in ectothermic animals such as reptiles. Endothermic animals would lose too much water without such turbinates, as they have to take more breaths because of their higher metabolic rate.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Victoria M. Arbor, Michael E. Burns, Robin L. Sissons: A redescription of the ankylosaurid dinosaur Dyoplosaurus acutosquameus Parks, 1924 (Ornithischia: Ankylosauria) and a revision of the genus. In: Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. Vol. 29, No. 4, 2009, ISSN 0272-4634 , pp. 1117-1135, doi : 10.1671 / 039.029.0405 .

- ^ A b c Richard S. Lull , Nelda E. Wright: Hadrosaurian Dinosaurs of North America (= Geological Society of America. Special Paper. Vol. 40, ISSN 0072-1077 ). Geological Society of America, New York NY 1942, pp. 206-208.

- ↑ David B. Weishampel : The nasal cavity of lambeosaurine hadrosaurids (Reptilia: Ornithischia): comparative anatomy and homologies. In: Journal of Paleontology. Vol. 55, No. 5, 1981, ISSN 0022-3360 , pp. 1046-1057.

- ↑ a b c d e f John R. Horner , David B. Weishampel, Catherine A. Forster: Hadrosauridae. In: David B. Weishampel, Peter Dodson , Halszka Osmólska (eds.): The Dinosauria . 2nd edition. University of California Press, Berkeley CA et al. 2004, ISBN 0-520-24209-2 , pp. 438-463.

- ^ A b Donald F. Glut : Dinosaurs. The Encyclopedia. McFarland, Jefferson NC et al. 1997, ISBN 0-89950-917-7 , pp. 478-482.

- ↑ a b c d John R. Horner, Philip J. Currie : Embryonic and neonatal morphology and ontogeny of a new species of Hypacrosaurus (Ornithischia, Lambeosauridae) from Montana and Alberta. In: Kenneth Carpenter, Karl F. Hirsch, John R. Horner (Eds.): Dinosaur Eggs and Babies. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1994, ISBN 0-521-44342-3 , pp. 312-336.

- ^ A b Charles W. Gilmore : On the genus Stephanosaurus, with a description of the type specimen of Lambeosaurus lambei, Parks. In: Canada, Department of Mines, Geological Survey. Bulletin. Vol. 38, No. 43, 1924, ZDB -ID 429582-1 , pp. 29-48.

- ↑ Michael Keith Brett-Surman: A Revision of the Hadrosauridae (Reptilia: Ornithischia) and their Evolution during the Campanian and Maastrichtian. The Faculty of The Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University, Washington DC 1989 (dissertation).

- ↑ Daisuke Suzuki, David B. Weishampel, Nachio Minoura: Nipponosaurus sachaliensis (Dinosauria; Ornithopoda): anatomy and systematic position within Hadrosauridae. In: Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. Vol. 24, No. 1, 2004, pp. 145-164, doi : 10.1671 / A1034-11 .

- ^ A b David C. Evans, Robert R. Reisz: Anatomy and Relationships of Lambeosaurus magnicristatus, a crested hadrosaurid dinosaur (Ornithischia) from the Dinosaur Park Formation, Alberta. In: Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. Vol. 27, No. 2, 2007, pp. 373-393, doi : 10.1671 / 0272-4634 (2007) 27 [373: AAROLM] 2.0.CO; 2 .

- ^ A b Barnum Brown : A new trachodont dinosaur, Hypacrosaurus, from the Edmonton Cretaceous of Alberta. In: Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. Vol. 32, Article 20, 1913, ISSN 0003-0090 , pp. 395-406, online .

- ^ Benjamin S. Creisler: Deciphering duckbills. In: Kenneth Carpenter (Ed.): Horns and Beaks. Ceratopsian and ornithopod Dinosaurs. Indiana University Press, Bloomington IN 2007, ISBN 978-0-253-34817-3 , pp. 185-210.

- ↑ Lawrence M. Lambe : On Cheneosaurus tolmanensis, a new genus and species of trachodont dinosaur from the Edmonton Cretaceous of Alberta. In: The Ottawa Naturalist. Vol. 30, No. 10, 1917, ISSN 0316-4411 , pp. 117-123, digitized .

- ^ William D. Matthew : Canadian dinosaurs. In: Natural History. Vol. 20, No. 5, 1920, ISSN 0028-0712 , pp. 536-544, digitized .

- ↑ Peter Dodson: Taxonomic Implications of Relative growth in Lambeosaurine Hadrosaurs. In: Systematic Zoology. Vol. 24, No. 1, 1975, ISSN 0039-7989 , pp. 37-54, doi : 10.1093 / sysbio / 24.1.37 .

- ^ A b David B. Weishampel, Paul M. Barrett , Rodolfo Coria , Jean Le Loeuff, Xing Xu , Xijin Zhao , Ashok Sahni, Elizabeth Gomani, Christopher R. Noto: Dinosaur distribution (Late Triassic, Africa). In: David B. Weishampel, Peter Dodson, Halszka Osmólska (eds.): The Dinosauria . 2nd edition. University of California Press, Berkeley CA et al. 2004, ISBN 0-520-24209-2 , pp. 517-683, here pp. 517-606.

- ^ Peter Dodson: The Horned Dinosaurs. A natural history. Princeton University Press, Princeton NJ 1996, ISBN 0-691-02882-6 , pp. 14-15.

- ^ Raymond R. Rogers: Taphonomy of three dinosaur bone beds in the Upper Cretaceous Two Medicine Formation of northwestern Montana; evidence for drought-related mortality. In: PALAIOS. Vol. 5, No. 5, 1990, ISSN 0883-1351 , pp. 394-413, doi : 10.2307 / 3514834 .

- ↑ Lisa N. Cooper, John R. Horner: Growth rate of Hypacrosaurus stebingeri as hypothesized from lines of arrested growth and whole femur circumference. In: Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. Vol. 19, Supplement to No. 3 = Abstracts of Papers Fifty-Ninth Annual Meeting Society of Vertebrate Paleontology, Adams Mark Hotel, Denver, Colorado October 20-23, 1999 , 1999, p. 35A.

- ↑ Lisa Noelle Cooper, Andrew H. Lee, Mark L. Taper, John R. Horner: Relative growth rates of predator and prey dinosaurs reflect effects of predation. In: Proceedings of the Royal Society. Series B: Biological Sciences. Vol. 275, No. 1651, 2008, ISSN 0080-4649 , pp. 2609-2615, doi : 10.1098 / rspb.2008.0912 , PMID 18682367 , PMC 2605812 (free full text).

- ↑ John A. Ruben, Willem J. Hillenius, Nicholas R. Geist, Andrew Leitch, Terry D. Jones, Philip J. Currie, John R. Horner, George Espe III: The metabolic status of some Late Cretaceous dinosaurs. In: Science . Vol. 273, No. 5279, 1996, pp. 1204-1207, doi : 10.1126 / science.273.5279.1204 .

- ↑ Anusuya Chinsamy, Willem J. Hillenius: Physiology of nonavian dinosaurs. In: David B. Weishampel, Peter Dodson, Halszka Osmólska (eds.): The Dinosauria . 2nd edition. University of California Press, Berkeley CA et al. 2004, ISBN 0-520-24209-2 , pp. 643-659.