Lambeosaurinae

| Lambeosaurinae | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Drawing life reconstruction of Lambeosaurus |

||||||||||||

| Temporal occurrence | ||||||||||||

| Upper Cretaceous (late Santonian to Maastrichtian ) | ||||||||||||

| 85.2 to 66 million years | ||||||||||||

| Locations | ||||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||||

| Lambeosaurinae | ||||||||||||

| Parks , 1923 |

The Lambeosaurinae is a taxon of the hadrosaurs . They can be found in fossils on the continents of North America and Asia from the Upper Cretaceous . The most important feature was a ridge that was formed from the intermaxillary bone ( premaxillary) and the nasal bone (nasal). The Lambeosaurinae are the hadrosaurs, which are more closely related to Lambeosaurus than to Hadrosaurus .

features

Hull and size

The Lambeosaurinae were built more robustly than the Hadrosaurinae. In contrast to their counterparts, they had high spinous processes ; which clearly raised the back and the base of the tail. Except for Olorotitan with 18 cervical vertebrae, the Lambeosaurinae, like all other hadrosaurs, had up to 15 cervical vertebrae. Another feature is that the spoke (radius) was longer than the upper arm bone (humerus).

The Lambeosaurinae were relatively large animals compared to the Hadrosaurinae. Most genera were 9 to 10 m long. Charonosaurus is estimated at a length of 13 m, Lambeosaurus even at a size of 15 to 16 m - that would make Lambeosaurus the largest Lambeosaurinae. For comparison: the largest Hadrosaurinae, Shantungosaurus , was about 14 m long. The oldest representative so far, Nipponosaurus , was a rather small Lambeosaurinae with 8 m.

skull

The most important feature of the Lambeosaurinae is the bone crest formed from the intermaxillary bone ( premaxillary) and nasal bone (nasal). The crest, which is usually directed backwards, varies in shape from bone-cone-like (e.g. Parasaurolophus ) to hatchet-shaped, flap-like or helmet-like (e.g. Corythosaurus ). In the genus Tsintaosaurus , the comb shape is controversial, but is often interpreted as unicorn-like . However, the comb can hardly be present. The size dimorphism in one species suggests that males and females had two different crests. The combs had tubes running through them, with which tones could be produced. There were 4 tubes in the combs, two upwards and two downwards; the air had to cross all the tubes.

As with all hadrosaurs, the snout was wide, but narrower than that of the Hadrosaurinae. In Lambeosaurus an outgrowth of the zygomatic bone (Jugale) pointing to the snout had a triangular shape.

Systematics and evolution

External system

The Lambeosaurinae is compared to the Hadrosaurinae . The main difference is that the Hadrosaurinae does not have a comb. Both taxa in turn form the taxon Euhadrosauria . Vecchia cladogram:

| Hadrosaurs (Hadrosauridae) |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Evolution and paleobiogeography

In the 1980s, the hadrosaur-like skull of the genus Ouranosaurus sparked a discussion. According to Philippe Taquet , the Ouranosaurus skull was so similar to the Hadrosaurs that it could be an ancestor of the Hadrosauridae, and thus an ancestor of the Lambeosaurinae. Jack Horner said in 1990 that Ouranosaurus had similar skull features as the Lambeosaurinae; thus Ouranosaurus and the Lambeosaurinae were combined as Lambeosauria. The Hadrosaurinae, on the other hand, are more closely related to Iguanodon . If this theory is correct, the hadrosaurs no longer form a monophyletic clade, but the Lambeosaurinae and the Hadrosaurinae would have developed from separate ancestors and other times. But this theory has not been proven.

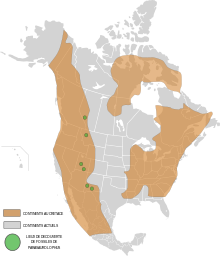

The origin of the Lambeosaurinae themselves was likely Asia . There the genera Aralosaurus and Jaxartosaurus split off. Part of a population also migrated towards China; there was the genus Tsintaosaurus . The other part of the population immigrated to North America via the Bering Strait . There the Parasaurolophini split off from the other Lambeosaurinae, the Corythosaurini , and formed the cone-like ridges by adapting to nature. Since the Lambeosaurinae were found more in the north than in the south of North America, this also speaks for this development. The North American Lambeosaurinae probably also migrated back to Asia. A good example of this theory are Charonosaurus and Parasaurolophus : both have snorkel-like crests. Since Charonosaurus is geologically younger than Parasaurolophus , Parasaurolophus may have immigrated to Asia. The Lambeosaurinae died in North America before the end of the Cretaceous, in Asia, however, they died out with all other non-avian dinosaurs at the end of the Cretaceous around 66 million years ago.

Internal system

The Lambeosaurinae can generally be divided into two tribes : the Parasaurolophini , with the snorkel-like crests, and the Corythosaurini with the "round" crests, to which the genus Lambeosaurus also belongs. The basal Lambeosaurinae include Tsintaosaurus and Olorotitan .

| Lambeosaurinae |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Paleobiology

Function of the combs

The function (s) of the combs of the lambeosaurs is controversial. In the past, the hadrosaurs were interpreted as amphibious animals; the crest could have been a kind of snorkel, especially with Parasaurolophus . Other suggestions are that the comb served as a salt gland or an expanded sense of smell. It is now assumed that the combs were colorful and were used in courtship. The cavities were connected to the windpipe and nose . Sounds could be generated with it.

Habitat and Paleoecology

It used to be assumed that the Lambeosaurinae lived amphibiously like other hadrosaurs. Richard Deckert depicted the genus Corythosaurus in water with a horizontal body, but on land Deckert reconstructed it standing on two legs. The first describer Barnum Brown concluded from the high, laterally flattened tail on a swimming way of life. This theory lasted for decades. Another support of this theory of the amphibious way of life was the snorkel-like crest of the Parasaurolophus .

Today we know that the Lambeosaurinae were terrestrial, i.e. animals that lived on land. In North America, the landscape was Alberta in the north crossed by rivers and marshy meadows and there was a from the Western Interior Seaway marine -influenced climate in New Mexico in South America was by the withdrawal of the Western Interior Seaways flooding level.

In Asia there was both desert and forest. Among other things, there were also some lakes.

Paleoecology

In the Dinosaur Park Formation in North America where Lambeosaurinae were found, many ceratopsians were also found, including Centrosaurus , Styracosaurus and Chasmosaurus , but the North American Lambeosaurinae shared their habitat with both the Hadrosaurinae Prosaurolophus and Gryposaurus , the ankylosaurids Edmontoniaus and Euoploceus , as well as the tyrannosauroid Gorgosaurus . In the Horseshoe Canyon Formation , also North America, the Lambeosaurinae shared the habitat with the Hadrosaurinae Edmontosaurus regalis and Saurolophus osborni , the Ceratopsier with the species Pachyrhinosaurus canadensis , Anchiceratops ornatus , Arrhinoceratops brachyops and Eotriceratops . Ankylosaurs , including Euoplocephalus tutus and Edmontonia longiceps or pachycephalosaurs such as Stegoceras edmontonense, were rather rare . The ornithopod Parksosaurus warrenae is also an ornithic . The theropods were very common with the ornithomimids such as Dromiceiomimus brevitertius , Ornithomimus edmontonicus and Struthiomimus altus . The top predator was the tyrannosaurid Albertosaurus sarcophagus . Smaller predators were Ricardoestesia isosceles , the Caenagnathids Chirostenotes pergracilis , the Troodontids Troodon formosus and the Dromaeosaurids Atrociraptor marshalli , Dromaeosaurus sp. and Saurornitholestes sp.

In Asia the Lambeosaurinae shared the habitat with the Hadrosaurine Kerberosaurus , the Protoceratopsiden Protoceratops , some pachycephalosaurs , the ankylosaur Saichania the habitat, theropods were represented by the genera Tarbosaurus and Velociraptor .

Diet

All Lambeosaurinae were herbivores . The advanced jaws allowed grinding movements. The chewing strips formed tooth batteries in which several hundred teeth were arranged; multiple teeth were always used. Worn teeth were constantly being replaced. The plants were first plucked with the beak and then held in cheek-like mouth areas. The paleontologist Robert Bakker said that the Lambeosaurinae have narrower snouts than the Hadrosaurinae. Bakker theorized that the lambeosaurine hadrosaurs were more picky herbivores.

History of discovery and research

1910 to 1930

The first known Lambeosaurinae was the Hypacrosaurus described by Barnum Brown in 1913 . It was originally known for the ribs , vertebrae , shoulder and pelvic girdles, and bones of limbs . Brown, however, noticed the giant stature and said this hadrosaur had an "erect height" almost that of the Tyrannosaurus and called it "almost the largest lizard". The shape of the skull became known in 1924 through a description of a second specimen. In 1914, Brown described Corythosaurus ; it was named after a remarkable find at Steveville on the Red Deer River , Alberta , in 1912. Except for part of the forelegs and tail, completely preserved. It is important, among other things, that the fossils of Corythosaurus are very well preserved, they show the outlines of the soft tissues of the entire animal, even the skin. Brown, however, was attentive to parallel, vertical folds; they were clearly visible in the shoulder and trunk. Brown said it was "loose skin folds" that must be visible in living animals. According to Brown, the Corythosaurus fossil showed vertical skin furrows in addition to high vertebral continuations . Richard Deckert reconstructed Corythosaurus for Brown's article with a folded skin surface. When Deckert reconstructed Corythosaurus swimming and standing upright on land with two legs, the theory that hadrosaurs were amphibious persisted in the early 20th century.

When the University of Toronto made an expedition to Alberta, the genus Parasaurolophus was discovered , also on the Red Deer River, in 1920 . The specimen is the holotype with the specimen number ROM 768. It consists of a partial skeleton with a skull, but the leg bones below the knee joints and most of the tail are missing. The animal was described by William Parks in 1922 and named it Parasaurolophus walkeri . However, some Parasaurolophus fossils were discovered as early as 1917 , but it was not until 1924 that Gilmore identified them as Lambeosaurus sp. described. The shape of the ridge was thought to have been used as a snorkel, which supports the theory that hadrosaurs were amphibious animals. Parks believed that Parasaurolophus was a close relative of Saurolophus , hence the name "almost Saurolophus ". However, Parks noted that the animal's snout resembled that of Corythosaurus and suspected a relationship between the two genera, which was also confirmed. Park's assumption that the bone plug was connected to the back with a skin collar was not confirmed, but the painter Charles Knight drew Parasaurolophus according to Park's assumption.

William Parks created the new genus Lambeosaurus in 1922 . The fossils were found in the Judith River Group in Dinosaur Provincial Park , Alberta . There were almost 20 relatively well-preserved skulls , sometimes with associated skeletons. Both adult and young animals were found. Another partial skeleton of Lambeosaurus was uncovered in the El Gallo formation in the Mexican state of Baja California Norte .

1930 to 1960

In 1931 a new species of the genus Parasaurolophus was discovered: Parasaurolophus tubicen . The species was described by Carl Wiman , but discovered as early as 1921. The species name tubicen comes from Latin and means "trumpeter".

A new species known as Nipponosaurus sachalinensis was discovered on Sakhalin Island in 1936 . It was described by the Japanese paleontologist Nagao. The name means "lizard from Japan " because the island once belonged to Japan, today it is ruled by Russia .

The paleontologist Anatoly Nikolajewitsch Ryabinin described the new, little-known species Jaxartosaurus aralensis , depending on the source in 1937 or 1939 .

No further Lambeosaurinae were discovered in the 1940s, it was not until 1958 that the Chinese paleontologist Yang Zhongjian described the new genus Tsintaosaurus . Tsintaosaurus is named after the city of Tsingtao (Qingdao). The only species is Tsintaosaurus spinorhinus ; the species name spinorhinus means "spiked nose ". It is the first known Lambeosaurinae to wear a unicorn-like comb.

1960 to 2000

Anatoli Konstantinowitsch Roschdestwenski described the species Aralosaurus tuberiferous in 1968 . The fossils of the genus were discovered in Kazakhstan in the Beleutinsk Formation near the Aral Sea . He is known for a partially preserved skull , some vertebrae , limb bones and individual teeth .

In 1993 Pararhabdodon isonensis was described by Casanovas-Cladellas , Santafe-Llopis and Isidoro Llorens . He was a possible relative of the Tsintaosaurus . One possible synonym is Koutalisaurus .

Recent discoveries

In 2000, a new species that looked similar to Parasaurolophus was described: Charonosaurus jiayinensis . It was found and excavated in the Yuliangze Formation as early as 1916/1917. The holotype is a fragmentary skull described as a Charonosaurus by Pascal Godefroit, Shuqin Zan, and Liyong Jin in 2000 .

In 2003 the Asian olorotitan was described. It was discovered in 1991 in the Udurchukan Formation (the lower part of the Tsagayan Group ).

Further discoveries from 2006 to 2010 were Koutalisaurus kohlerorum , Nanningosaurus dashiensis , Velafrons coahuilensis , Sahaliyania elunchunorum , Arenysaurus ardevoli , Angulomastacator daviesi and Blasisaurus canudoi .

In popular culture

Although most of the Lambeosaurinae are fairly unknown, there are a few species that are common in documentaries, films, etc. The most famous dinosaur of this subfamily is Parasaurolophus . He appears in the films In a Land Before Time (although actually a Saurolophus ), in the section “Le sacre du Printemps” from Disney's Fantasia , in all three Jurassic Park films and Disney's Dinosaurs . The Parasaurolophus is also popular as a toy . B. manufactured in the Schleich company. The genus Corythosaurus appears in a great many popular science books. Other, less well-known genera include Lambeosaurus and Tsintaosaurus .

Web links

Individual evidence

- ^ Gregory S. Paul : The Princeton Field Guide To Dinosaurs. Princeton University Press, Princeton NJ et al. 2010, pp. 306-316, ISBN 978-0-691-13720-9 , online ( July 13, 2015 memento on the Internet Archive ).

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p John R. Horner , David B. Weishampel , Catherine A. Forster: Hadrosauridae. In: David B. Weishampel, Peter Dodson , Halszka Osmólska (eds.): The Dinosauria . 2nd edition. University of California Press, Berkeley CA et al. 2004, ISBN 0-520-24209-2 , pp. 438-463.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i Lambeosaurinae on thescelosaurus.com ( Memento from August 4, 2009 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Richard S. Lull , Nelda E. Wright: Hadrosaurian Dinosaurs of North America (= The Geological Society of America. Special Papers. No. 40, ISSN 0072-1077 ). The Geological Society of America, New York NY 1942, pp. 209-213.

- ↑ a b c d Pascal Godefroit, Yuri Bolotsky, Vladimir Alifanov: A remarkable hollow-crested hadrosaur from Russia: an Asian origin for lambeosaurines. In: Comptes Rendus Palevol. Vol. 2, No. 2, 2003, ISSN 1631-0683 , pp. 143-151, doi : 10.1016 / S1631-0683 (03) 00017-4 .

- ↑ Donald F. Glut : Parasaurolophus. In: Donald F. Glut: Dinosaurs. The Encyclopedia. McFarland & Co, Jefferson NC et al. 1997, ISBN 0-89950-917-7 , pp. 678-684.

- ↑ a b www.enchantedlearning.com - Corythosaurus (en)

- ↑ a b c Tsintaosaurus on Dinoruss.com (webarchive) ( Memento from May 24, 2008 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Charonosaurus . In: Luis V. Rey's Art Gallery Dinosaurs and Paleontology. Archived from the original on July 7, 2009 ; accessed on October 22, 2014 (English).

- ^ Robert M. Sullivan, Thomas E. Williamson: A new skull of Parasaurolophus (Dinosauria: Hadrosauridae) from the Kirtland Formation of New Mexico and a revision of the genus (= New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science. Bulletin. 15, ISSN 1524-4156 ). New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science, Albuquerque NM 1999, digitized .

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Darren Naish: The fascinating discovery of the dinosaur. Konrad Theiss Verlag GmbH, Stuttgart 2010, ISBN 978-3-8062-2325-5 .

- ↑ Michael J. Benton : Paleontology of the vertebrates. Pfeil, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-89937-072-0 , p. 226.

- ^ A b Robert T. Bakker : The Dinosaur Heresies. New Theories Unlocking the Mystery of the Dinosaurs and their Extinction. William Morrow, New York NY 1986, ISBN 0-688-04287-2 , p. 194.

- ↑ Fabio M. Dalla Vecchia: Tethyshadros insularis, a new hadrosauroid dinosaur (Ornithischia) from the Upper Cretaceous of Italy. In: Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. Vol. 29, No. 4, 2009, ISSN 0272-4634 , pp. 1100-1116, doi : 10.1671 / 039.029.0428 .

- ↑ a b Pascal Godefroit, Shuqin Zan, Liyong Jin: Charonosaurus jiayinensis ng, n.sp., a lambeosaurine dinosaur from the Late Maastrichtian of northeastern China. In: Comptes Rendus de l'Académie des Sciences. Series 2, Fascicule A: Sciences de la Terre et des Planètes. Vol. 330, No. 12, 2000, ISSN 0764-4450 , pp. 875-882, doi : 10.1016 / S1251-8050 (00) 00214-7 .

- ^ David A. Eberth: The Geology. In: Philip J. Currie , Eva B. Koppelhus (Eds.): Dinosaur Provincial Park. A spectacular ancient ecosystem revealed. Indiana University Press, Bloomington IN et al. 2005, ISBN 0-253-34595-2 , pp. 54-82.

- ^ Dale A. Russell : An odyssey in time. The dinosaurs of North America. NorthWord Press et al., Minocqua WI et al. 1989, ISBN 1-55971-038-1 , pp. 160-164.

- ↑ Dinosaurs - In the Realm of Giants: The Riddle of the Giant Claw. BBC, 2002.

- ↑ David B. Weishampel, Paul M. Barrett , Rodolfo Coria , Jean Le Loeuff, Xing Xu , Xijin Zhao , Ashok Sahni, Elizabeth Gomani, Christopher R. Noto: Dinosaur distribution. In: David B. Weishampel, Peter Dodson, Halszka Osmólska (eds.): The Dinosauria . 2nd edition. University of California Press, Berkeley CA et al. 2004, ISBN 0-520-24209-2 , pp. 517-683, here pp. 517-606.

- ^ David A. Eberth: Edmonton Group. In: Philip J. Currie (Ed.): Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs. Academic Press, San Diego CA et al. 1997, ISBN 0-12-226810-5 , pp. 199-204.

- ↑ Edmonton Group (www.dinoruss.com / webarchive) ( Memento of 27 June 2008 at the Internet Archive )

- ↑ You Hailu, Peter Dodson: Basal Ceratopsia. In: David B. Weishampel, Peter Dodson, Halszka Osmólska (eds.): The Dinosauria . 2nd edition. University of California Press, Berkeley CA et al. 2004, ISBN 0-520-24209-2 , pp. 478-493.

- ^ Matthew K. Vickaryous, Teresa Maryańska , David B. Weishampel: Ankylosauria. In: David B. Weishampel, Peter Dodson, Halszka Osmólska (eds.): The Dinosauria . 2nd edition. University of California Press, Berkeley CA et al. 2004, ISBN 0-520-24209-2 , pp. 363-392.

- ↑ Tomasz Jerzykiewicz, Dale A. Russell: Late Mesozoic stratigraphy and vertebrates of the Gobi Basin. In: Cretaceous Research. Vol. 12, No. 4, 1991, ISSN 0195-6671 , pp. 345-377, doi : 10.1016 / 0195-6671 (91) 90015-5 .

- ^ William A. Parks : Parasaurolophus Walkeri. A new genus and species of crested Trachodont dinosaur (= University of Toronto Studies. Geology Series. Vol. 13, ISSN 0372-4913 ). University of Toronto - University Library, Toronto 1922, digitized .

- ↑ David C. Evans, Robert R. Reisz, Kevin Dupuis: A juvenile Parasaurolophus (Ornithischia: Hadrosauridae) Braincase from Dinosaur Provincial Park, Alberta, with comments on crest ontogeny in the genus. In: Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. Vol. 27, No. 3, 2007, pp. 642-650, doi : 10.1671 / 0272-4634 (2007) 27 [642: AJPOHB] 2.0.CO; 2 .

- ↑ Carl Wiman: Parasaurolophus tubicen n. Sp. from the chalk in New Mexico (= Nova acta Regiae Societatis Scientiarum Upsaliensis. Series 4, Vol. 7, No. 5, ZDB -ID 210356-4 ). Almqvist & Wiksell, Uppsala 1931.

- ^ David P. Simpson: Cassell's Latin - English, English - Latin Dictionary. 5th edition. Cassell et al., London et al. 1979, p. 883.

- ^ The "In a Land Before Our Time" DVD ( Memento from February 17, 2009 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Fantasia (1940). In: Movie Mistakes. Retrieved August 19, 2009 .

- ↑ Parasaurolophus. In: Park Pedia. Retrieved August 19, 2009 .

- ↑ Disney Dinosaur Interviews David Krentz. In: The DINOSAUR Interplanetary Gazette. Archived from the original on October 28, 2010 ; Retrieved July 8, 2013 .

- ↑ Parasaurolophus on Schleich.com ( Memento from September 24, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) (en)